Art and Technology | Impact on artist practices at the turn of the 21st century in India

In the ‘90s India witnessed a tectonic shift when erstwhile finance minister Manmohan Singh’s liberalization policies transitioned India into a free market economy, with increased foreign direct investment. The percolation of technology seeped through the country’s (primarily urban) landscape, with internet being made publicly available in 1995 (Mint 2015) and 4G in 2010 (Ghosh and Mishra 2015). In this period, the influx of the internet through social networks, websites, online streaming services, and the e-commerce industry revolutionized how we travelled, communicated, shopped, consumed culture, and of course, made art.

This article is a condensation of my written and oral interviews with 11 Indian contemporary artists whose art practices were initiated in the ‘90s. This temporal sub-set of artists aids a sharper study about the “before” and “after”, providing a glimpse into the impact of liberalization on their practices. The scope of my query attempts to understand how the growth of access to information, social media platforms which changed the quality of information shared, rapid developments in technology like film, audio and video projection, affected art practices before and after this internet boom. The essay is not concerned with “technology in art” broadly, but specifically on the impact technology has had on existing art practices of that time.

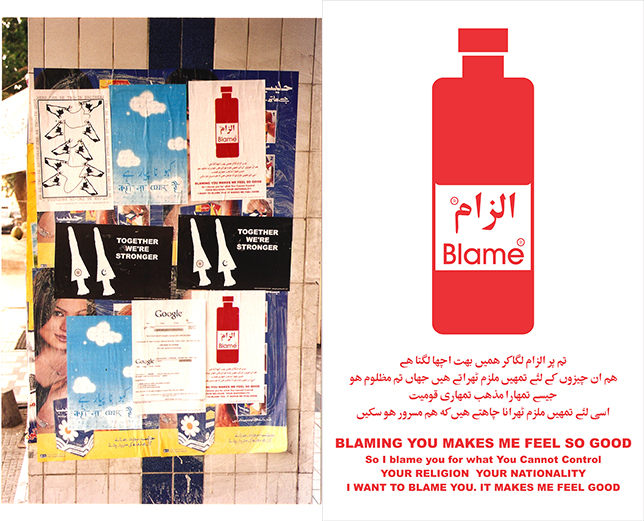

Aar Paar, which took place simultaneously in Mumbai and Karachi in 2000 and 2002[1], included ten artists from each city who developed single colour works which were exchanged across the two countries via email, to be printed locally and inserted into public spaces (Mulji 2000)

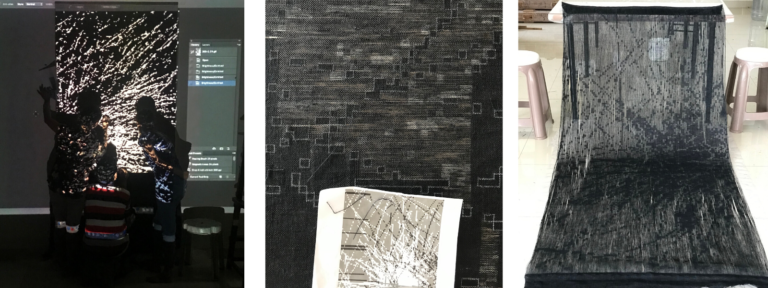

In contrast, researching in mid-2000s for the last words spoken by famous people in Last Words, First Cry, was easier as the information was found online without the aid of a physical library or reading biographies (Choksi 2019). Some artists affirm that the increasing types of technologies – video projection, audio recordings, digital printing – expanded the range of artists’ practices to include film and photography as mediums. The most prominent example is that of Gigi Scaria, who was exposed to a digital camera in 2001 in Italy, which were unavailable in India at the time. This led him to make his first video work in 2002 through a TRV25 Sony movie camera and because of that, film and audio based art work formed a crucial part of his ongoing practise (Scaria 2019).

Subsequently, processes for the documentation of artwork to understand mediums better, the scale of their work, as well as maintainence of records, changed rapidly for the artists. Jitish Kallat recalls working on a 20 ft painting in the mid-90s in a 10 ft by 10 ft room, and to understand how the final artwork was taking shape he would photograph sections of it. Then, a “one-hour-photo” studio would print them from the negative of the camera roll and he would place them together to understand the larger whole. This today can be viewed by him on his laptop soon after “stitching” photos clicked by his phone (J. Kallat 2019).

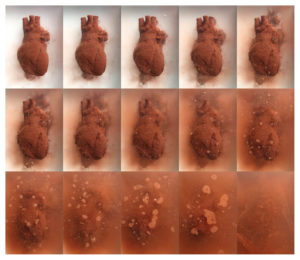

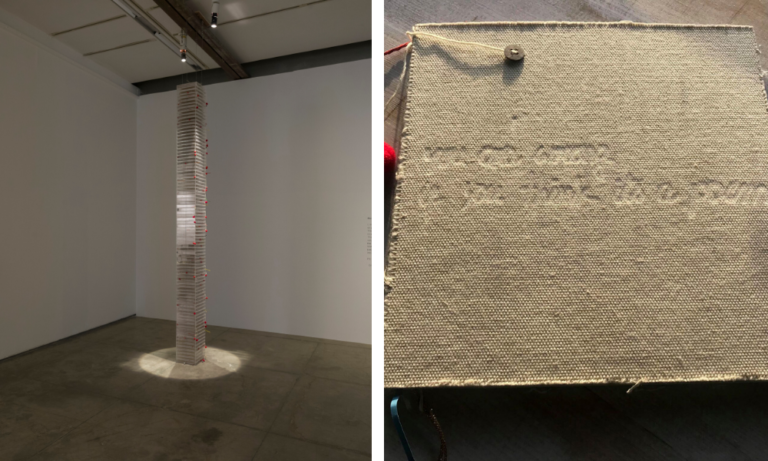

Yardena Kurulkar’s Kenosis, 2017 takes this engagement with technology a step further where 3D printing enabled her to do something un-precedented: excavate her own internal organ—the heart—and create an exact replica of it (Kurulkar 2019).

A similar evolution is also seen in the role of printing and photocopying devices. ‘In the 90s, the fax machine and photocopy machine, the camera – were my collaborators’ recalls Kallat as he used to incorporate them as participants in his creative process (J. Kallat 2019). Gupta recalls small naka shops of xerox machines and desktop publishing counters and printers, where she used to lay out the text of the two-page arts school newsletter she published during the mid-90s. In this, enlarging and reducing the size of an image, or decreasing and increasing the size of any font being used in an art-work required repeated efforts (Acharya 2019). This same ecosystem of small printers and photocopy machine outlets are still readily available today, “still are very much part of one’s extended studio, shared and on the streets” (Gupta 2019).

Overtime, the type of dependency on machines has shifted. Any desktop computer or laptop now aids in assessing exact layouts in the preparatory stages of artwork creation. This increased efficiency also aids in matching color schemes to placing diptychs and triptychs together, so paint, canvases and other raw materials are procured down to the exact requirement.

Additionally, former training and experience of the artists impacted how they navigated this transitory phase. Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra provide an interesting contrast because both their postgraduate degrees are in visual communication and communication design, respectively, and hence there was a seamless adoption of newer computer software and programmes as the internet age beckoned them (Thukral and Tagra 2019). Being part of the advertising world also kept Acharya in grips with the changing technological landscape.

Slowly, it became about sifting from the information that is constantly coming towards artists, rather than seeking it out from scratch. Viewing interviews, archival material, academic research, images online now does not necessitate the number of library visits or largescale field research which were the norm earlier. Information has been accessible on our handheld devices in the last decade, and on PC and laptop computers since the early 2000s (Rajaraman 2012).

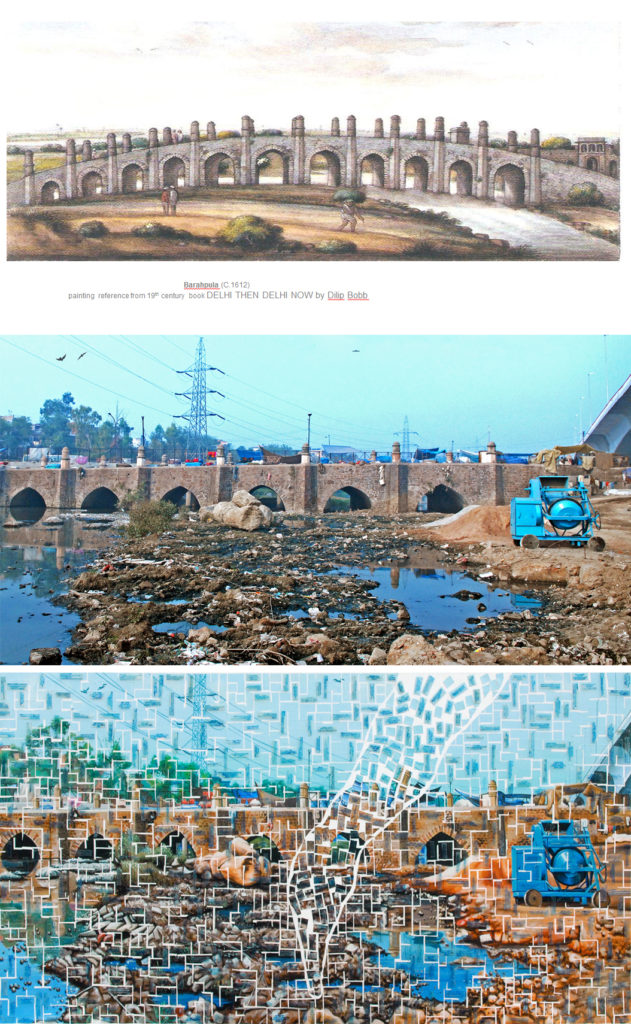

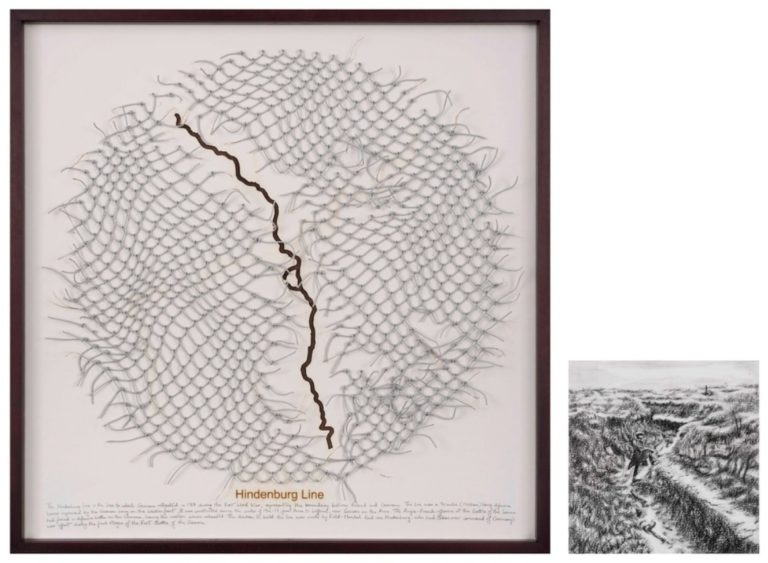

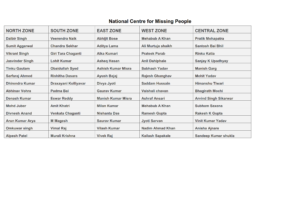

Reena Kallat espouses this when she explains that her research for Falling Fables, 2011 and Synonyms, 2009 required setting up meetings through landlines with ASI officials, police stations, VISA offices, months or sometimes years in advance, to now accessing the details of such endangered heritage sites, missing persons reports’ and visa denial reports available online.

This shift enabled Kallat’s Hyphenated Lives, 2015 and Leaking Lines, 2019 series, to expand their scope from regional information about border disputes within South Asia to looking at global disruptions through international territorial disputes, like US-Cuba, Israel-Palestine, Germany-Poland and Croatia-Serbia (R. Kallat 2019).

Evolution, not Inception | Ideas about Art

In this burgeoning technical landscape, our conversations also highlighted anchors that ground an artists’ practice in an overwhelming mass of information, and the closing gap between the real and virtual worlds. Jitish Kallat sequentially contextualizes global information received with a time-lag throughout the 80s to the 2000s, to real time information in multiple modes all the time after that. To indulge and abstain at the same time from this powerful influx of constant information is the balance he recommends to artists today, and practises himself, by not creating a presence on Instagram or Facebook. Acharya mentions that social media platforms can offer glimpses into the processes of art-making when artists post images of works in progress or making-of videos, but it can also create an alternate virtual reality of only successfully completed art works, shying away from the angst, turbulences, failings, doubt, half-attempts that any artist goes through in their practice. This creates a different set of expectations in today’s world, as compared to a time when the art works in books and the art works of peers were the only barometers to compare one’s work with. In a striking contrast, these interactions with audiences through social media have added another element to the performative part of Mithu Sen’s practice, which she continues to explore (Sen 2019).

Nai mentions how his collaboration is more dependent on the technical expertise of civil engineers, carpenters, aluminum framers, than on technology in and of itself. Similarly, Tagra and Thukral echoed how more information about the aspects of the farmers crises’ is more widely available since they have been researching for their interactive experiential art work Bread, Circuses & TBD 2019, but in no way does that undermine the act of engaging with the farmers in Punjab to create a knowledge base to create artwork from.

Learning & Pedagogy | A Changed Audience

Acharya and Kurulkar poignantly mention that to learn any art technique outside of art school, or to access an art critic’s article, or see art works of other artists, their only options were books, the slide library and exhibition catalogues. Overtime, how one “learnt” about art changed and is changing. Accessing information about art through online international art journals, magazines and blogs was possible. Witnessing conversations about art taking place across the globe through panel discussions on YouTube, as well as online certified art courses from auction houses and universities evolved the pedagogy of art, not just for artists, but for the art viewing audience as well.

The value of the exhibition catalogue has evolved from being the only segue into an artists’ past exhibitions to now being virtually available as a nifty PDF circulated on WhatsApp or through AirDrop. The digital footprint of artwork documentation is much larger with handheld phone cameras, sophisticated art management systems like Art Logic, or even simply, professional cameras that record artwork and exhibition displays. Along with instant real time video and photo documentation of exhibitions today, breakthroughs in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality globally (Bonasio 2018) and in South Asia, significantly impact how audiences are consuming art. With the explosion of viewing images of art through many platforms other than just where the art work is displayed—mobile apps, social media platforms on phones and virtual reality tours on computers—an audience can get art-fatigued faster and it can become a unique challenge for artists to now hold the audience’s attention and sustain it.

Future-Proofing (?) And Reflecting

Receiving responses to my questions about the transformative impact of the influx of technology highlighted changes in artwork production, documentation and scope that occurred as an immediate by-product of technological advancements. It helped map the significant long-term shifts in making, learning, sharing, seeing, and thinking about art, that came to the fore. As echoed by many artists who were interviewed, this proliferation of technology helped and helps in the evolution of the artwork, but not in the inception of the artwork itself. It can be understood that technology has impacted artists’ practices at the turn of the millennia, be it through research scope, access to information, documentation, pedagogy as well as the audiences that consume art. Though there is one response which has resonated collectively across most of the artists referred to in the essay: that the human connection is the core for creating, interacting with, ideating about—art. It cannot be replaced with, but only complemented by, technological advancement.

Notes

Refer to Printing across borders: the Aar-Paar Project by Chaitanya Sambrani, presented at the Fifth Australian Print Symposium, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2004

Acharya, Dhruvi, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Adam, Georgina. 2018. Financial Times Art Market Collecting. 27 July. https://www.ft.com/content/9c5e3fe8-85ea-11e8-9199-c2a4754b5a0e.

Bonasio, Alice. 2018. Forbes. 20 June. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alicebonasio/2018/06/20/augmented-reality-will-reinvent-how-we-experience-art/#7f05bafc636c.

Choksi, Neha, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Ghosh, Shauvik, and Ashish K. Mishra. 2015. The Birth of the Internet in India. 30 June. https://www.livemint.com/Industry/R3kgewhIhKscbiELV1sHZM/The-birth-of-the-Internet-in-India.html.

Gupta, Shilpa, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (October).

Iyengar, Radhika. 2018. Can Artificial Intelligence impact art in the 21st century? 25 August . https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/SpfgErhSDzACR1j8UDfkFJ/Can-Artificial-Intelligence-impact-art-in-the-21st-century.html.

Kallat, Jitish, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Kallat, Reena, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Kurulkar, Yardena, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Matney, Lucas. 2018. Art.com adds augmented reality art-viewing to its iOS app. 1 February . https://techcrunch.com/2018/02/01/art-com-adds-augmented-reality-art-viewing-to-its-ios-app/.

—. 2018. Tech Crunch. 1 February. https://techcrunch.com/2018/02/01/art-com-adds-augmented-reality-art-viewing-to-its-ios-app/.

McAndrew, Dr Clare. 2018. The Art Market 2018 An Art Basel & UBS Report. UBS.

Mint, Live. 2015. A Brief History of the Internet. 18 July. https://www.livemint.com/Industry/bQkp9arbe4mlaJHQA1xOjO/A-brief-history-of-the-Internet.html.

Mulji, Shilpa Gupta and Hema. 2000. aarpaar 2002 and 2000. http://www.members.tripod.com/aarpaar2/02.htm.

Nai, Manish, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Rajaraman, V. 2012. History of Computing in India 1955-2010. Bangalore: IEEE Computer Society History Committee.

Sambrani, Chaitanya. 2004. “Printing across borders: the Aar-Paar Project.” The Fifth Australian Print Symposium, National Gallery of Australia. Canberra.

Samdanis, Marios. 2016. “The Impact of New Technology on Art.” In Art Business Today : 20 Key Topics, by M. (2016)J. Hackforth-Jones Samdanis and I. Robertson, 164-172. London: Lund Humphries.

Scaria, Gigi, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Sen, Mithu, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Singh, Aditi, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (October).

Sussman, Anna Louie. 2017. Artsy by ArtNet. 22 August. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-industries-drive-art-market.

Thukral, Jiten, and Sumir Tagra, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

[1] Refer to Printing across borders: the Aar-Paar Project by Chaitanya Sambrani, presented at the Fifth Australian Print Symposium, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2004

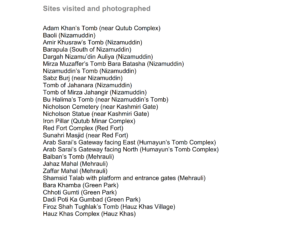

Appendix: List of physical sites and databases compiled as part of Reena Saini Kallat’s research.

About The Author

Shaleen Wadhwana has woven her academic and professional life extensively around the arts and heritage sector. Along with degrees in BA History (Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi) and MA Art History (SOAS, London), she has academic expertise in Art Appreciation (National Museum Institute, Delhi), was awarded the Scholarship of Excellence for Cultural Heritage Law (University of Geneva) and is a Young India Fellow (Ashoka University). She has presented her academic research on embedded histories in objects looted during the 1857 Great Uprising at University College London, England as well as on the repatriation politics surrounding the Kohinoor Diamond at India’s first Art Laws Conference, at the Piramal Learning University, Mumbai.

She has worked at museums and galleries ranging from the Heritage Transport Museum, Haryana to Chemould Prescott Road Gallery, Mumbai. Shaleen curates art and heritage based experiences for a wide spectrum of audiences ranging from universities like Michigan and Harvard to NGOs like Slam Out Loud and institutions like the Tribal Development Board of the Govt. of Maharashtra and Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER). Currently, a visiting faculty at the Design Management Department of MITID Institute of Design in Pune, Shaleen is also the Humanities curriculum designer for the MITID Innovation programme. OSMOSIS, a contemporary art group show which was on display at TARQ Gallery in Mumbai, marks the beginning of her curatorial journey, the idea of which was born in her classroom in Pune. Her recently co-authored article about the impact of the Lodi Art District on the community around it, for the Ministry of External Affairs of India, has been published in India Perspectives, its widely read international e-journal.