What Does It Mean

To Make Disappearing Images

In a Disappearing World?

On Anuja Dasgupta’s anthotypes

and the aesthetics of ecological fragility

AUTHOR

Drishya

In the visual economies of the ongoing climate crisis, the domain of photography is often concerned with documenting evidence of our environmental degradation. Satellite images record and archive planetary climate change, both in real-time and over vast timescales. Aestheticized infographics about extreme weather events and ecological disasters circulate endlessly on the internet, offering both data and doom narratives of our impending climate dystopias. This seems futile in the face of widespread environmental apathy and its slow decline in the anthropocene. What if, in the face of this seemingly inevitable, unstoppable, and inescapable environmental collapse, photographs were to embody the condition of the climate crisis rather than document its after-effects? What if the act of fading was not a failure of the form, but a philosophical position that aligned with the lived realities of the climate collapse?

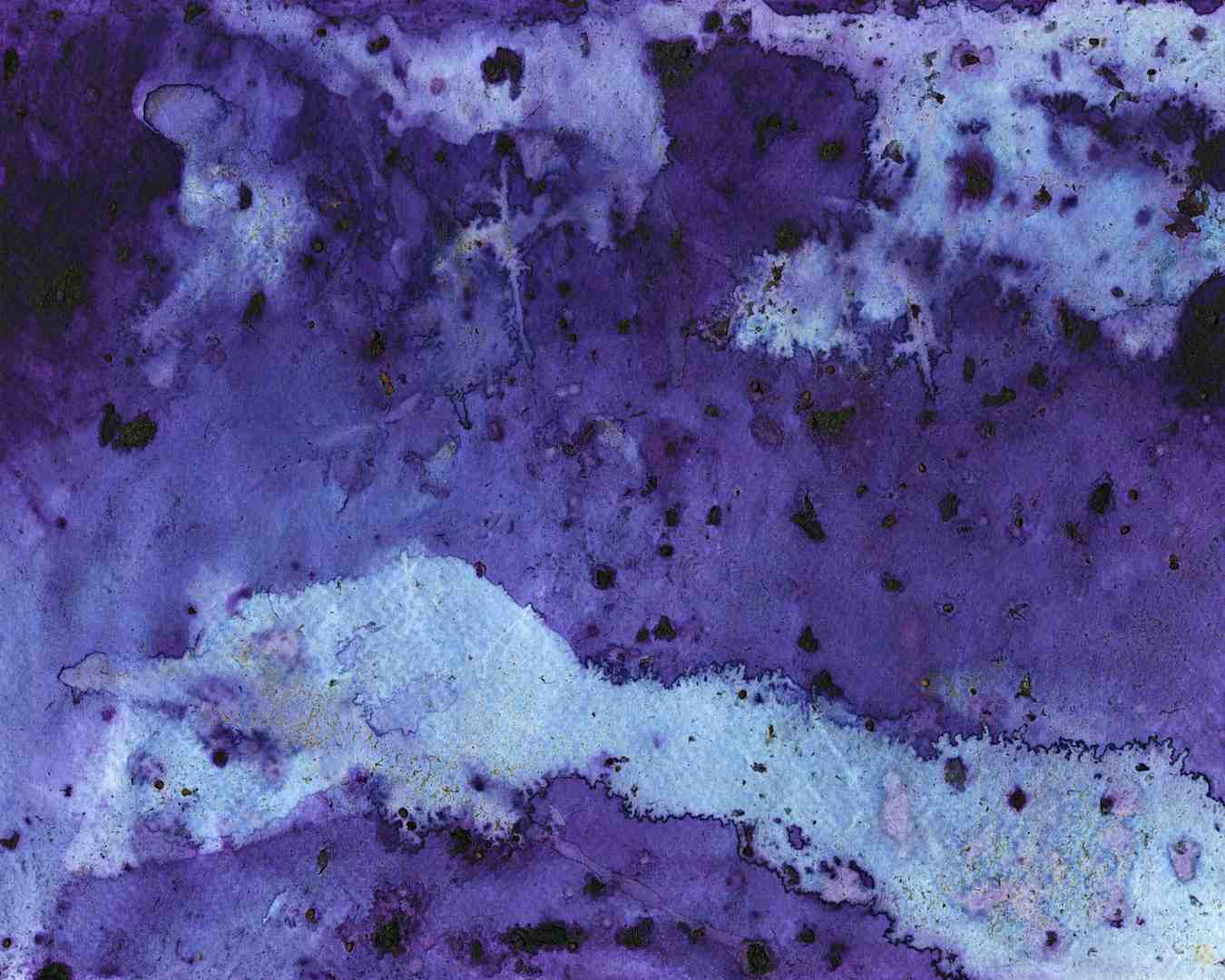

These are the questions that lay the foundation for the work of visual artist Anuja Dasgupta. Dasgupta’s camera-less photographs resist the permanence and precision of conventional photographic media, embracing instead the aesthetics of fragility, decay, and the ephemerality of the natural world. Working primarily with anthotypes—images created with photo-sensitive plant-based pigments and exposed to direct sunlight—Dasgupta responds to the climate crisis by embodying its conditions. When exposed to sunlight, her anthotypes change colour and continue to fade thereafter. This process of fading represents a form of acceptance of the impermanence of the natural world, in her work.

The anthotype process is one of photography’s oldest and most poetic alternative techniques. Invented by the Scottish scientist Mary Somerville in 1845, the anthotype process gets its name from the Greek words ‘anthos’, meaning ‘flower’, and ‘typos’, meaning ‘imprint’. Somerville developed the process as an alternative to Sir John Herschel’s cyanotype process, using photosensitive pigments extracted from fruits, flowers, roots, and other parts of plant bodies instead of a solution of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate to create images. By exposing these plant extracts to different parts of the solar spectrum, Somerville discovered that different spectral exposures produced different colours from the same plant, revealing an alchemical connection between light and life. However, as photography shifted toward commercial and archival ambitions and faster chemical processes such as the daguerreotype and tintype became more popular, the anthotype process—with its fragility, slowness, and impermanence—was relegated to the domain of the more un-urgent photography, in the conventional sense.. Dasgupta’s work reclaims this alternative image-making process as a provocative gesture towards humility and resistance in the anthropocene. By moving away from photographic permanence towards ecological impermanence, she transforms this historic process into a modern aesthetic of resistance.

In ‘Elemental Whispers’ (2022-present), an ongoing body of work created in the trans-Himalayan landscape of Ladakh, where Dasgupta lives and works, she collects fallen leaves, flowers, and wild, uncultivated berries and botanical matter from high-altitude riverbanks and rocky slopes to produce imprints of the delicate Himalayan ecosystems. She pounds these plant materials with a pestle, distils them into photosensitive emulsions, and brushes the emulsion onto sheets of watercolour paper. The coated sheets are then placed at various sites along the Indus River, where sunlight, river drift, birds, insects, and animals leave their marks on the surface. The final image is not a frozen slice of time but what Dasgupta describes as a “meditative pull towards the silent rhythms of natural forces that create, care for, and cast existence on earth.”[1]

Dasgupta’s anthotypes not only resist the camera as an extractive tool but also the conventional photographic medium’s compulsion to fix, preserve, and archive. In Dasgupta’s hands, anthotypes become an alternative mode of seeing that values impermanence, contingency, and collaboration with non-human and more-than-human agents. Dasgupta aligns her practice with the instability of the very ecosystem she lives and works within by allowing her anthotypes to fade — to embody the conditions of the Anthropocene not by depicting its violence, but by rejecting its narrative of control.

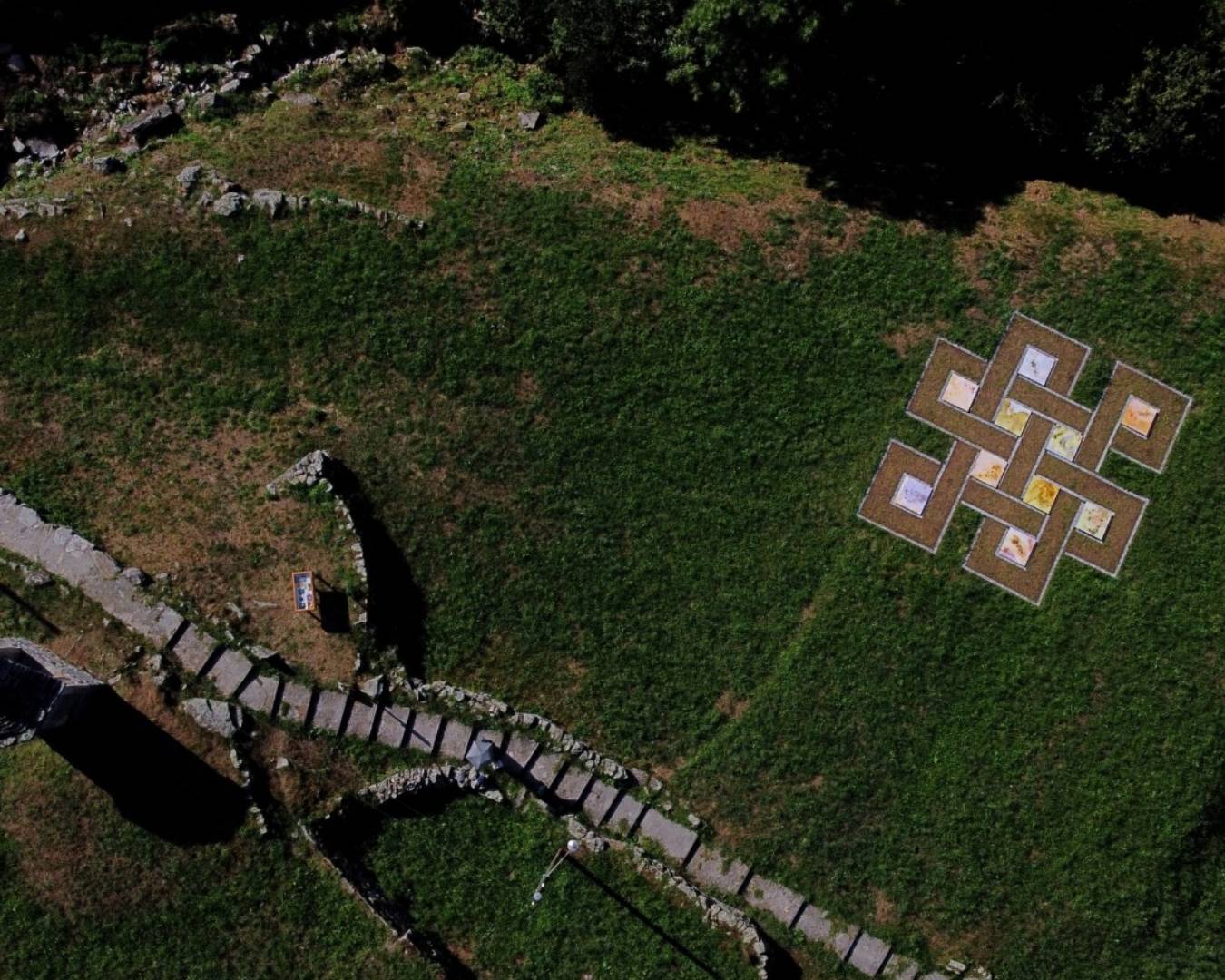

This pursuit continues in ‘How Does a River Breathe?’, a large-scale, site-specific installation of ten anthotypes that Dasgupta produced and staged in the Valle Verzasca, Switzerland, in 2024. Exposed beside the Verzasca River, using the river water as a developer, these images bear the marks of local fauna, flora, and sunlight. In these images, the concept of authorship dissolves and a collaboration between botanical chemistry, spectral light, and the agency of non-human life comes to the fore. Dasgupta installed them outdoors in a trail shaped like the endless knot with an indistinguishable beginning and end — an ancient symbol of continuity and entanglement rooted in trans-Himalayan cultures. Viewers were encouraged to walk this loop, becoming participants in a meditation on the interconnectedness of life, the living, and the lifelines that connect them. In Dasgupta’s words, ‘each viewer becomes a participant in the making of the endless knot: a gentle intersection of trans-Himalayan culture with the Verzasca landscape and a visual composition that echoes the interconnected physiology of the natural world.’[2]

There is also an elegiac undertone to this mode of image-making. As pollinator populations decline and flowering plants evolve to fertilize their seeds with their pollen—an evolutionary phenomenon known as ‘selfing’, which leads to reduced biodiversity and increased vulnerability to disease and environmental stress takes place, and the very life forms that make anthotypes possible become endangered. The disappearing image becomes both a metaphor and a memorial of a vanishing world — a brief collaboration between humans and a non-human world, under threat that the human world poses.

In resisting the extractive tendencies of conventional photography, Dasgupta’s anthotypes propose a radically different mode of seeing — one rooted in a profound recognition of the other, the more-than-human, and the rest of the world. By surrendering authorship to natural processes, Dasgupta critiques extractive visual traditions and de-centres anthropocentric narratives. This act of letting go provides an opportunity for what the British philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch called ‘unselfing’. In The Sovereignty of Good (1970), Murdoch defined ‘unselfing’ as the practice of de-centring the ego to attend to the world from a place of care. “Goodness is connected with the attempt to see the unself,” Murdoch wrote, “to see and to respond to the real world in the light of a virtuous consciousness.”[3]

In Dasgupta’s work, this act of ‘unselfing’ manifests materially. By surrendering the authorship of the image to natural processes like fading, disintegration, and uncertainty, she enacts a moral and philosophical re-vision: one where humans are no longer the axis along which the world is ordered.

Permanence is not a neutral ambition — within it are encoded fantasies of dominance, preservation, and control. But Dasgupta is not concerned with making permanent images; her practice is about unmaking the assumptions that govern photographic representation. Her ephemeral anthotypes challenge our fantasies of anthropocentrism; they gesture towards resistance against dominant ideas of the anthropocene, extractive seeing, and the image as a form of possession. To look at her work is to see the photographic image as a form of attentiveness rather than assertion. In their slowness, their softness, and their impermanence, Dasgupta’s anthotypes represent a recalibration of what it means to witness environmental change and make disappearing images in a disappearing world.

Notes

- Anuja Dasgupta, Elemental Whispers (2022–Present)

- Anuja Dasgupta, How Does A River Breathe? (2024)

- Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good (1970)