The Botanical Imagination

It is a truth now universally acknowledged, not least in recent articles in The Guardian and the BBC that the extinction of plants spells “bad news for all species,” and is being rapidly exacerbated by human destruction of the natural world. According to Dr Rob Salguero-Gómez from the University of Oxford, plants provide us with “food, shade and construction materials,” as well as “‘ecosystem services’ such as carbon fixation, oxygen creation, and even improvement in human mental health through enjoying green spaces.”

With the irreplaceable role of plants in our lives and surroundings, it is no surprise that artists have continually depicted the botanical world for both aesthetic and documentation purposes. Poised between art and science, botanical art has both aesthetic and utilitarian value. In India, this genre is largely associated with the Kampani (Company) school of painting, a naturalistic Indo-European style that became prevalent in the late 18th century when the East India Company sought to document the flora of the country. But depictions of plants go back much further in Indian art history, and were seen “on temple walls, pottery designs, motifs on woven carpets and embroidered textiles, […] illustrated folios from medieval manuscripts of Hindu epics,” and detailed in highly stylised forms in miniature art.

It is not only plants that face extinction. In Marg magazine’s recent issue (December 2018 – March 2019) titled Ars Botanica: The Weight of a Petal, historian and curator Sita Reddy says, “Today, with botanical art disappearing by the archive, and trees, forests or entire ecosystems at the whim of a malicious executive order, it seems more urgent than ever to compile some of these dispersed art historical resources. To refigure the botanical archive.”

While Marg drew attention to the rich, vibrant and largely unacknowledged history of botanical art in India, this essay seeks to explore the work of three contemporary Indian women artists who use plants as a motif, medium and metaphor to comment on issues of both personal and global significance. Belonging to a generation that has been educated in various sciences, the “diversity of interest [of these artists] allows for an exploration of the transcultural through the lens of the sciences, which function in a “universalist” sense wherever science is practiced – even if context favors one direction over another.” Incorporating but looking beyond aspects such as documentation and revival, the artists explore the botanical as an inquiry and a recreation of memories, reminding us of the value of our ecosystems and why we should be concerned about their loss.

GARDENS FROM THE PAST

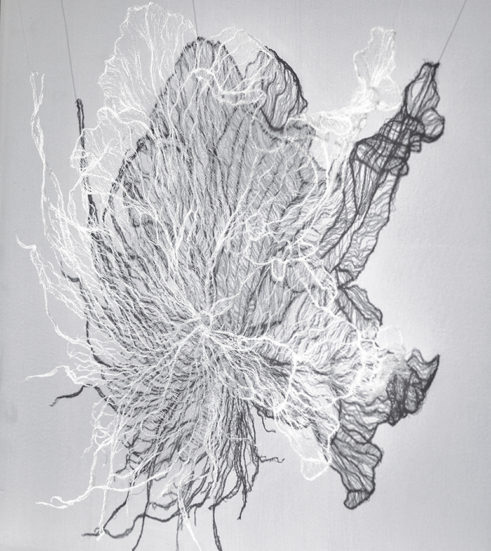

For Samanta Batra Mehta, nature is “a metaphor for the body (and vice-versa) and as a site for germination, nourishment, degradation, trespass, plunder, colonisation and transgression.” Though the plant forms she depicts are an artistic rendering rather than an exact replica, they are informed by historical botanical illustrations, and by observing the plants in places where she has travelled and lived, including Mumbai and New York.

Mehta also draws upon accounts and memories of the ornamental and kitchen gardens created by her grandfather – a botanist, college professor and agricultural scientist who fled violence during the Partition of 1947 – which he had to leave behind and eventually nurtured again in North India. Mehta says that “these fantastical gardens conjured by my families’ collective imagination, the larger debates underpinning them and themes in my own migration to New York appear frequently in my art.” She pays homage to her grandparents’ journey in Return to the Garden, 2019, where she “transcends time” by superimposing botanical and anatomical drawings, symbolising life, in red ink on vintage photographs and antique book leaves.

Samanta Batra Mehta, (top) Return to the Garden; (bottom) detail images, 2019, ink drawings made with hand dipped stylus, vintage/antiquarian photographs, book pages, map (20 parts), installation variable, approx. 75 x 75 inches. Photo courtesy the artist and Tarq Gallery, Mumbai

PAGES WITH PRESSED FLOWERS

A GREENHOUSE OF POSSIBILITIES

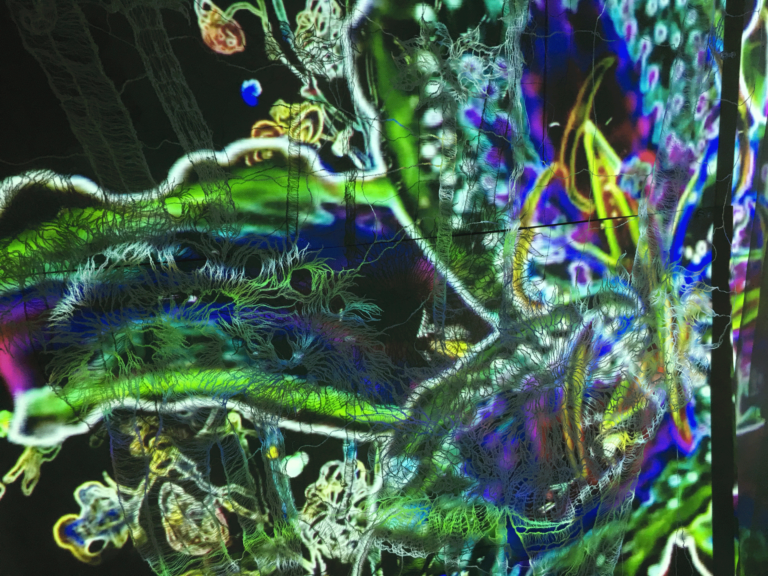

Elsewhere, Devasher said that she had been “exploring some ideas put forward in Goethe’s Botanical writings in which Goethe’s search for “that which was common to all plants without distinction” led him to evolve a purely mental concept of the archetypal plant. This archetype, when translated into art by some of his followers, resulted in what one writer has described as a ‘botanist’s nightmare’ consisting of all known leaves and flowers combined around a single stem. […] What result are hybrid organics that float in a twilight world between imagined and observed reality…forms in constant flux, in a state of continuous transformation. They could be denizens of a science-fictional botanical garden, specimens in a bizarre cabinet of curiosity or portents of a distant future.”

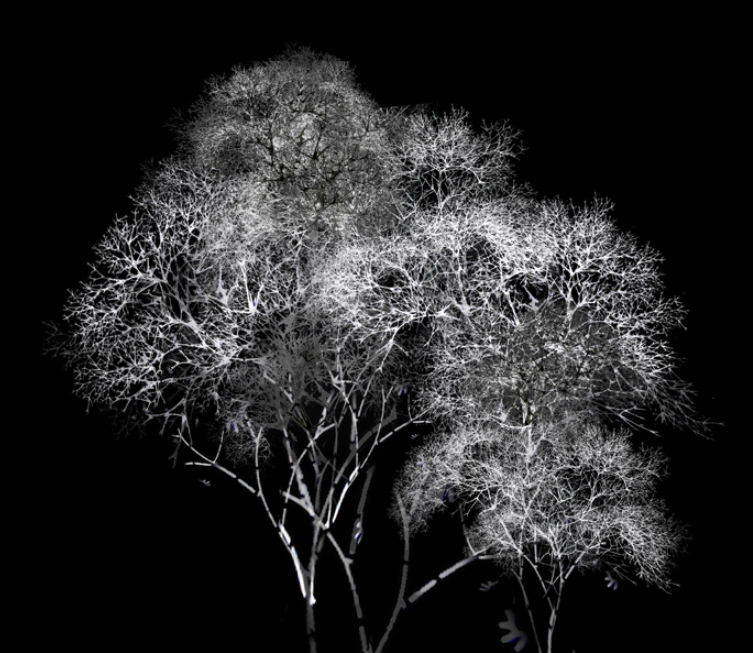

Interested in patterns, Devasher thinks of the botanical as a way to explore the mathematical in an engaging manner. In Arboreal, 2011, a video and photography-based work, the artist draws upon the Lindenmayer system of modelling plant growth and development. The recursive nature of the system creates branching, or fractal forms reminiscent of trees in the natural world. According to an exhibition statement by gallery Nature Morte, “If we consider the Arboreal video to be the archetype or ideal tree, then the Arboreal prints are a window to the other trees that could also have been. Once again these are generated by the layering of selected still frames of video, stacked one on top of the other. What results is a digital forest, a greenhouse of possibilities.”

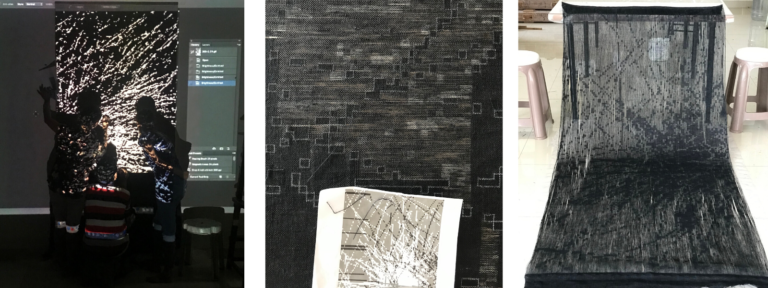

The speculative or science-fictional perspective is explored in works such as AtlasPhaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants, 2018 and the Genetic Drift series, which are as much about botanical accuracy as subverting it to consider a new visual vocabulary altogether. Atlas draws from specimens found in the R. L. McGregor Herbarium at the University of Kansas, deposited as far back as 1893, but the artist alters them to resemble varied animal forms. The process of creation involved photographing the specimens, and then modifying the images using Photoshop, pencils and acrylic. The series Genetic Drift presents hybrids – layered composites created using nearly 300 photographs and drawings collected by the artist in botanical gardens across the world.

About The Author

Artificial Intelligence (AI): The pathway to immortality or extinction?

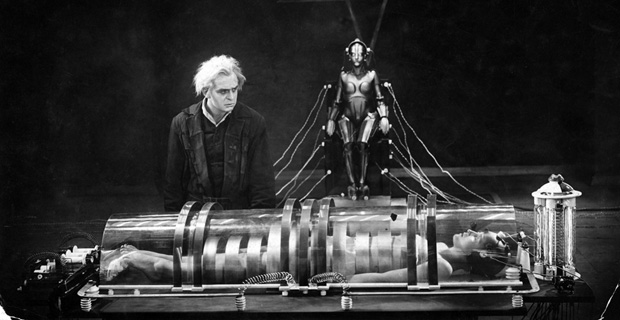

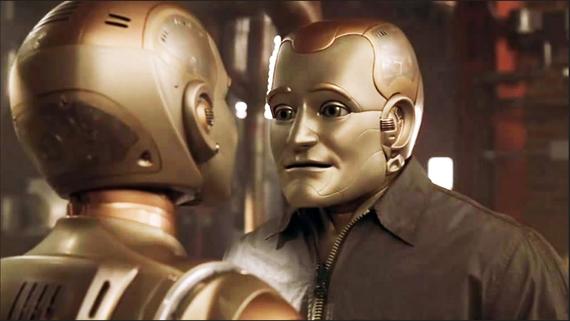

While A.I. was directed by Steven Spielberg it was originally conceived by none other than Stanley Kubrick himself in the late ’70s. Based on a short story titled “Super-Toys Last All Summer Long” by Brian Aldiss, A.I. Artificial Intelligence, as envisaged by Kubrick, was meant to be a robot version of Pinocchio. But Kubrick had to drop the idea when he realized that computer animation was not advanced enough to create the character of David, the Mecha child who dreams of becoming a real boy for his mommy who has adopted him to fill the void created by her real son’s rare medical condition that has indefinitely placed him in a state of suspended animation. The underlying trouble was that Kubrick was hooked to the idea of building a robot boy using computer graphics instead of casting a boy actor for the part of David as he feared that a human actor might look too human. Also since Kubrick took time to shoot his films, there was a risk that the boy would age and therefore change considerably during the time. Finally in the year 1995, he decided to handover the project to his longtime friend and fellow filmmaker Steven Spielberg.

Kubrick was somehow convinced that only Spielberg, known for meeting tight deadlines, could do justice to the story both emotionally (having already made a film like E. T.) as well as on the technical front (having just made Jurassic Park). For some reason or the other the project kept on getting delayed but after Kubrick’s sudden death in 1999, Spielberg took it up on a priority basis, even getting Tom Cruise’s consent before postponing the shooting schedule of Minority Report (2002) in order to realize his friend’s dream project. Spielberg, the most commercially successful filmmaker of all time, often gets lauded for his ability to deliver humongous blockbusters that are often loaded with cutting-edge computer graphics. But people often forget that what really makes these films tick is how well Spielberg handles the human emotions: be it the alien in E.T. or the Mecha child in A.I. or the giant in The BFG. Also, Spielberg is often accused of selling escapism in the name of cinema but those who understand his work well are aware that even his most commercial films endeavor to ask moral questions about the way the human society operates.

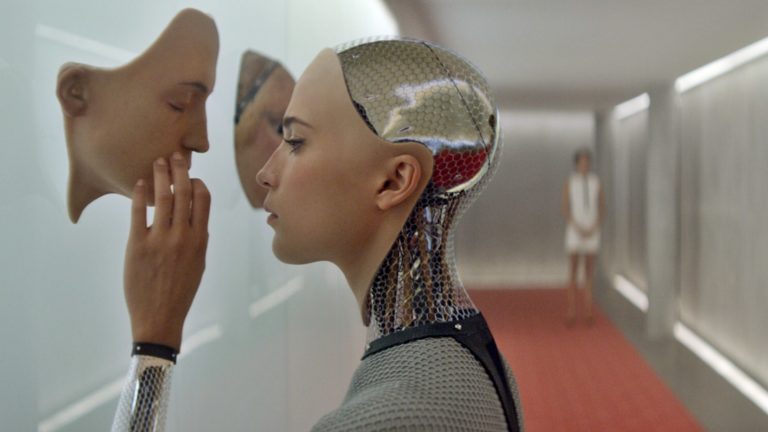

Now, A.I. despite all its fanfare is not one of his typical commercial films. A lot of questions that A.I. asks have actually become the basis of not only how cinema looks at AI characters but also how the human society may look at artificial intelligence in the times to come. The question that’s central to A.I. Artificial Intelligence is that if a robot could genuinely love a human being, what responsibility does that person hold towards that robot in return? While the idea of human beings loving back robots, or for that matter, artificial intelligence based programs in the real world may seem a bit farfetched at this point in time, films such as Blade Runner, Her, Ex Machina, Blade Runner 2049, and even Enthiran to some extent have already taken us in that direction as far as cinematic possibilities are concerned. But the human societies in none of these films talk about robot rights.

In the context of sentient robots gaining rights and becoming capable of loving other beings, an important question about their changing status in the futuristic societies also arises. Will they continue to serve the mankind or will they ever challenge their authority? Popular film series like The Terminator and The Matrixhave already introduced us to dystopian worlds dominated by the machines. On the other hand, the HBO series Westworld, inspired by a 1973 film of the same name written and directed by the noted Sci-Fi author Michael Crichton, depicts a struggle between the humans and the android hosts in technologically advanced Wild-West-themed amusement park originally built to gratify its wealthy patrons. Blade Runner and Blade Runner 2049 too pit the human race against the bio-engineered synthetic humans called replicants.

Even as Sophia continues to improve in terms of its outwardly similarities to the human beings in the real world, the humanoid robots in the aforementioned films and series have become so good that passing the Turing Test is no longer a concern for them. The real test, just as a character in Ex Machina says while referring to an AI named Ava with a human-looking face but a robotic body, is “to show you that she’s a robot and then see if you still feel she has consciousness”. In the film, Ava slowly transforms into a beautiful girl and is able to escape to the outside world and merge with the human population. Perhaps, the day is not too far when the likes of Sophia would be freely walking amongst us. And then perhaps there will also come a time when the AI, bestowed with the gift of immortality, will mock the ephemerality of the human life à la David8in Alien: Covenant.

Perfecting the AI is perhaps the biggest challenge that’s ever been presented to mankind. But the day it is perfected, the human race is certainly set to lose its supremacy to a superior race. The likes of Black Mirror, Love, Death & Robots, Ex Machina, and Westworld have already prepared us for the worst. But not all future possibilities look so grim. With AI already entering our lives there are endless benefits that await us. Now, the Steven Spielberg blockbuster Minority Report, based on the short story by the noted Sci-Fi author Philip K. Dick, talks about a futuristic world wherein PreCrime, a specialized police department, stops murderers ever before they commit the heinous act. On similar lines, the UK is trying to develop an AI-based system that will analyze police records and assign individuals with a risk factor for committing future crimes.

The Netflix series Altered Carbon, based on a 2002 novel by Richard K Morgan, is set in a futuristic world wherein human consciousness can be stored digitally and downloaded into new bodies. Already a startup called Humai working in the field of artificial intelligence and nanotechnology is trying to develop a technology to transfer human consciousness to a robot’s body. If such a breakthrough is made, the human life wouldn’t be so ephemeral after all. The animated film WALL·E set in the distant future tells the story of a waste-collecting robot. Mankind can certainly do with an army of such robots. Today, the biggest problems that the world is facing have environmental origins. Perhaps, AI can offer some solutions. Only recently at an Amazon event, actor Robert Downey Jr. shared his plans to launch a foundation that would use AI and nanotechnology to clean up the environment.

So, as we look at the future, even as the dark, dystopian, and diabolical threats of artificial intelligence continue to lurk in the remotest crevices of our minds, the human race looks set to embrace the rise of AI and the new revolution that it will usher in the field of medicine, genetics, architecture, biotechnology, travel and transportation, VR, surveillance, food production and preservation, prosthetics, cryogenics, and plastic surgery, among others. What was earlier only possible in the world of science fiction has today become a reality. There is little doubt that the thought leaders of science fiction, now more than ever will continue to be at the forefront of scientific innovation. All we can hope for is that while riding this unstoppable juggernaut of technological advancement we also succeed in rubbing off our humanity on the sentient beings that we may end up creating one day. Perhaps then we can rightfully claim to have perfected the AI.

About The Author

Art and Technology | Impact on artist practices at the turn of the 21st century in India

In the ‘90s India witnessed a tectonic shift when erstwhile finance minister Manmohan Singh’s liberalization policies transitioned India into a free market economy, with increased foreign direct investment. The percolation of technology seeped through the country’s (primarily urban) landscape, with internet being made publicly available in 1995 (Mint 2015) and 4G in 2010 (Ghosh and Mishra 2015). In this period, the influx of the internet through social networks, websites, online streaming services, and the e-commerce industry revolutionized how we travelled, communicated, shopped, consumed culture, and of course, made art.

This article is a condensation of my written and oral interviews with 11 Indian contemporary artists whose art practices were initiated in the ‘90s. This temporal sub-set of artists aids a sharper study about the “before” and “after”, providing a glimpse into the impact of liberalization on their practices. The scope of my query attempts to understand how the growth of access to information, social media platforms which changed the quality of information shared, rapid developments in technology like film, audio and video projection, affected art practices before and after this internet boom. The essay is not concerned with “technology in art” broadly, but specifically on the impact technology has had on existing art practices of that time.

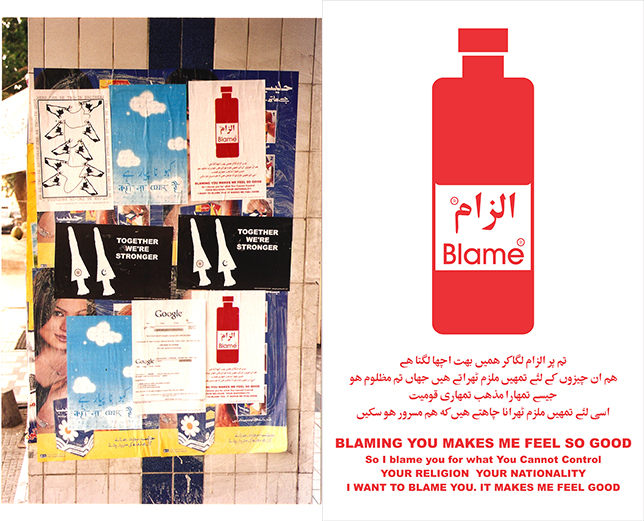

Aar Paar, which took place simultaneously in Mumbai and Karachi in 2000 and 2002[1], included ten artists from each city who developed single colour works which were exchanged across the two countries via email, to be printed locally and inserted into public spaces (Mulji 2000)

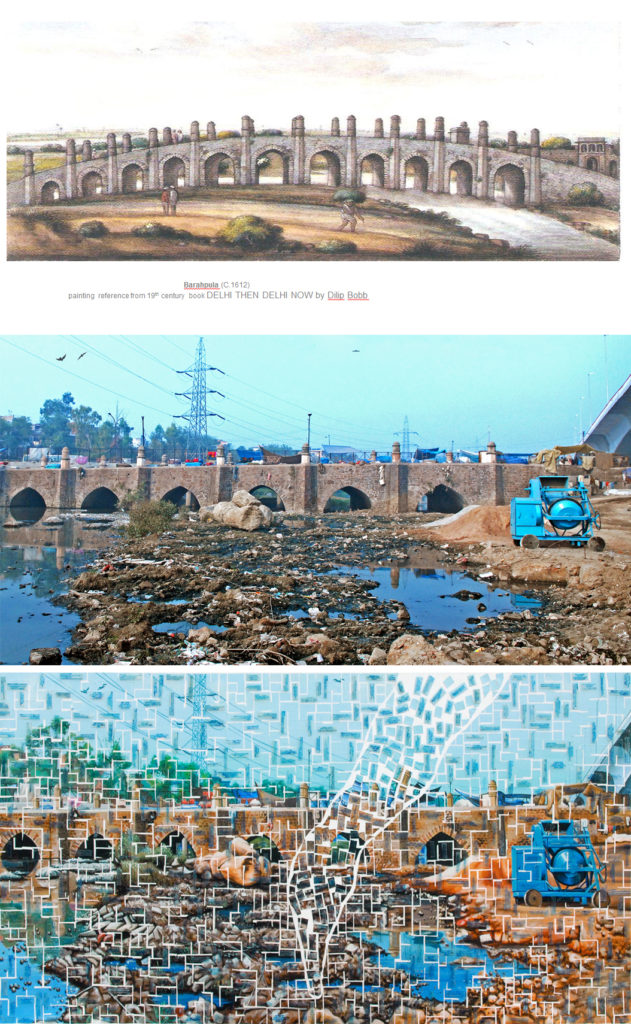

In contrast, researching in mid-2000s for the last words spoken by famous people in Last Words, First Cry, was easier as the information was found online without the aid of a physical library or reading biographies (Choksi 2019). Some artists affirm that the increasing types of technologies – video projection, audio recordings, digital printing – expanded the range of artists’ practices to include film and photography as mediums. The most prominent example is that of Gigi Scaria, who was exposed to a digital camera in 2001 in Italy, which were unavailable in India at the time. This led him to make his first video work in 2002 through a TRV25 Sony movie camera and because of that, film and audio based art work formed a crucial part of his ongoing practise (Scaria 2019).

Subsequently, processes for the documentation of artwork to understand mediums better, the scale of their work, as well as maintainence of records, changed rapidly for the artists. Jitish Kallat recalls working on a 20 ft painting in the mid-90s in a 10 ft by 10 ft room, and to understand how the final artwork was taking shape he would photograph sections of it. Then, a “one-hour-photo” studio would print them from the negative of the camera roll and he would place them together to understand the larger whole. This today can be viewed by him on his laptop soon after “stitching” photos clicked by his phone (J. Kallat 2019).

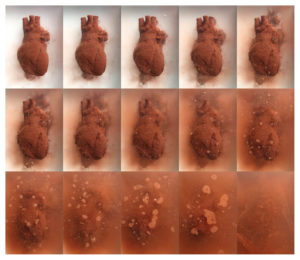

Yardena Kurulkar’s Kenosis, 2017 takes this engagement with technology a step further where 3D printing enabled her to do something un-precedented: excavate her own internal organ—the heart—and create an exact replica of it (Kurulkar 2019).

A similar evolution is also seen in the role of printing and photocopying devices. ‘In the 90s, the fax machine and photocopy machine, the camera – were my collaborators’ recalls Kallat as he used to incorporate them as participants in his creative process (J. Kallat 2019). Gupta recalls small naka shops of xerox machines and desktop publishing counters and printers, where she used to lay out the text of the two-page arts school newsletter she published during the mid-90s. In this, enlarging and reducing the size of an image, or decreasing and increasing the size of any font being used in an art-work required repeated efforts (Acharya 2019). This same ecosystem of small printers and photocopy machine outlets are still readily available today, “still are very much part of one’s extended studio, shared and on the streets” (Gupta 2019).

Overtime, the type of dependency on machines has shifted. Any desktop computer or laptop now aids in assessing exact layouts in the preparatory stages of artwork creation. This increased efficiency also aids in matching color schemes to placing diptychs and triptychs together, so paint, canvases and other raw materials are procured down to the exact requirement.

Additionally, former training and experience of the artists impacted how they navigated this transitory phase. Jiten Thukral and Sumir Tagra provide an interesting contrast because both their postgraduate degrees are in visual communication and communication design, respectively, and hence there was a seamless adoption of newer computer software and programmes as the internet age beckoned them (Thukral and Tagra 2019). Being part of the advertising world also kept Acharya in grips with the changing technological landscape.

Slowly, it became about sifting from the information that is constantly coming towards artists, rather than seeking it out from scratch. Viewing interviews, archival material, academic research, images online now does not necessitate the number of library visits or largescale field research which were the norm earlier. Information has been accessible on our handheld devices in the last decade, and on PC and laptop computers since the early 2000s (Rajaraman 2012).

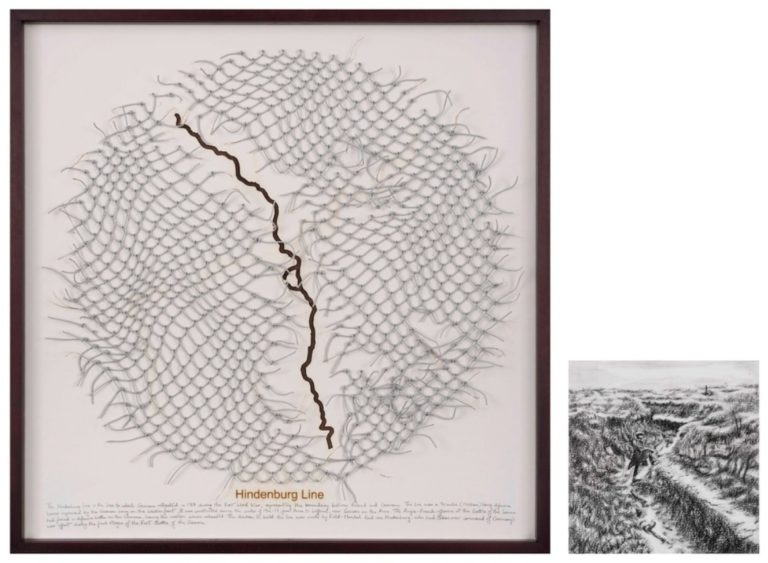

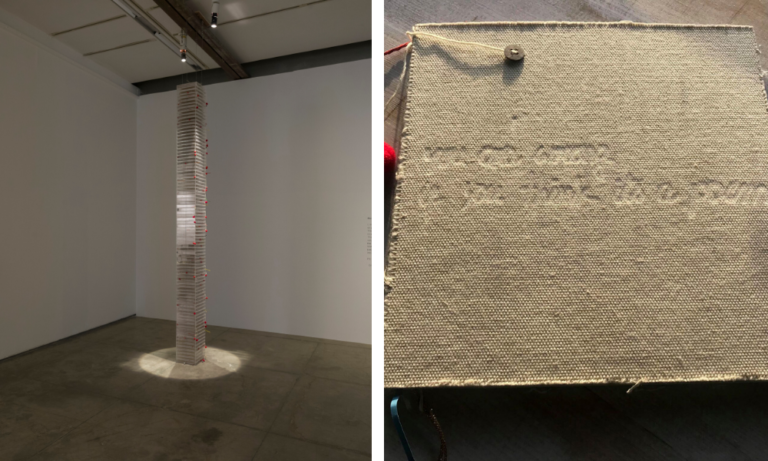

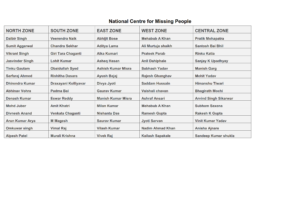

Reena Kallat espouses this when she explains that her research for Falling Fables, 2011 and Synonyms, 2009 required setting up meetings through landlines with ASI officials, police stations, VISA offices, months or sometimes years in advance, to now accessing the details of such endangered heritage sites, missing persons reports’ and visa denial reports available online.

This shift enabled Kallat’s Hyphenated Lives, 2015 and Leaking Lines, 2019 series, to expand their scope from regional information about border disputes within South Asia to looking at global disruptions through international territorial disputes, like US-Cuba, Israel-Palestine, Germany-Poland and Croatia-Serbia (R. Kallat 2019).

Evolution, not Inception | Ideas about Art

In this burgeoning technical landscape, our conversations also highlighted anchors that ground an artists’ practice in an overwhelming mass of information, and the closing gap between the real and virtual worlds. Jitish Kallat sequentially contextualizes global information received with a time-lag throughout the 80s to the 2000s, to real time information in multiple modes all the time after that. To indulge and abstain at the same time from this powerful influx of constant information is the balance he recommends to artists today, and practises himself, by not creating a presence on Instagram or Facebook. Acharya mentions that social media platforms can offer glimpses into the processes of art-making when artists post images of works in progress or making-of videos, but it can also create an alternate virtual reality of only successfully completed art works, shying away from the angst, turbulences, failings, doubt, half-attempts that any artist goes through in their practice. This creates a different set of expectations in today’s world, as compared to a time when the art works in books and the art works of peers were the only barometers to compare one’s work with. In a striking contrast, these interactions with audiences through social media have added another element to the performative part of Mithu Sen’s practice, which she continues to explore (Sen 2019).

Nai mentions how his collaboration is more dependent on the technical expertise of civil engineers, carpenters, aluminum framers, than on technology in and of itself. Similarly, Tagra and Thukral echoed how more information about the aspects of the farmers crises’ is more widely available since they have been researching for their interactive experiential art work Bread, Circuses & TBD 2019, but in no way does that undermine the act of engaging with the farmers in Punjab to create a knowledge base to create artwork from.

Learning & Pedagogy | A Changed Audience

Acharya and Kurulkar poignantly mention that to learn any art technique outside of art school, or to access an art critic’s article, or see art works of other artists, their only options were books, the slide library and exhibition catalogues. Overtime, how one “learnt” about art changed and is changing. Accessing information about art through online international art journals, magazines and blogs was possible. Witnessing conversations about art taking place across the globe through panel discussions on YouTube, as well as online certified art courses from auction houses and universities evolved the pedagogy of art, not just for artists, but for the art viewing audience as well.

The value of the exhibition catalogue has evolved from being the only segue into an artists’ past exhibitions to now being virtually available as a nifty PDF circulated on WhatsApp or through AirDrop. The digital footprint of artwork documentation is much larger with handheld phone cameras, sophisticated art management systems like Art Logic, or even simply, professional cameras that record artwork and exhibition displays. Along with instant real time video and photo documentation of exhibitions today, breakthroughs in Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality globally (Bonasio 2018) and in South Asia, significantly impact how audiences are consuming art. With the explosion of viewing images of art through many platforms other than just where the art work is displayed—mobile apps, social media platforms on phones and virtual reality tours on computers—an audience can get art-fatigued faster and it can become a unique challenge for artists to now hold the audience’s attention and sustain it.

Future-Proofing (?) And Reflecting

Receiving responses to my questions about the transformative impact of the influx of technology highlighted changes in artwork production, documentation and scope that occurred as an immediate by-product of technological advancements. It helped map the significant long-term shifts in making, learning, sharing, seeing, and thinking about art, that came to the fore. As echoed by many artists who were interviewed, this proliferation of technology helped and helps in the evolution of the artwork, but not in the inception of the artwork itself. It can be understood that technology has impacted artists’ practices at the turn of the millennia, be it through research scope, access to information, documentation, pedagogy as well as the audiences that consume art. Though there is one response which has resonated collectively across most of the artists referred to in the essay: that the human connection is the core for creating, interacting with, ideating about—art. It cannot be replaced with, but only complemented by, technological advancement.

Notes

Refer to Printing across borders: the Aar-Paar Project by Chaitanya Sambrani, presented at the Fifth Australian Print Symposium, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2004

Acharya, Dhruvi, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Adam, Georgina. 2018. Financial Times Art Market Collecting. 27 July. https://www.ft.com/content/9c5e3fe8-85ea-11e8-9199-c2a4754b5a0e.

Bonasio, Alice. 2018. Forbes. 20 June. https://www.forbes.com/sites/alicebonasio/2018/06/20/augmented-reality-will-reinvent-how-we-experience-art/#7f05bafc636c.

Choksi, Neha, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Ghosh, Shauvik, and Ashish K. Mishra. 2015. The Birth of the Internet in India. 30 June. https://www.livemint.com/Industry/R3kgewhIhKscbiELV1sHZM/The-birth-of-the-Internet-in-India.html.

Gupta, Shilpa, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (October).

Iyengar, Radhika. 2018. Can Artificial Intelligence impact art in the 21st century? 25 August . https://www.livemint.com/Leisure/SpfgErhSDzACR1j8UDfkFJ/Can-Artificial-Intelligence-impact-art-in-the-21st-century.html.

Kallat, Jitish, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Kallat, Reena, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Kurulkar, Yardena, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Matney, Lucas. 2018. Art.com adds augmented reality art-viewing to its iOS app. 1 February . https://techcrunch.com/2018/02/01/art-com-adds-augmented-reality-art-viewing-to-its-ios-app/.

—. 2018. Tech Crunch. 1 February. https://techcrunch.com/2018/02/01/art-com-adds-augmented-reality-art-viewing-to-its-ios-app/.

McAndrew, Dr Clare. 2018. The Art Market 2018 An Art Basel & UBS Report. UBS.

Mint, Live. 2015. A Brief History of the Internet. 18 July. https://www.livemint.com/Industry/bQkp9arbe4mlaJHQA1xOjO/A-brief-history-of-the-Internet.html.

Mulji, Shilpa Gupta and Hema. 2000. aarpaar 2002 and 2000. http://www.members.tripod.com/aarpaar2/02.htm.

Nai, Manish, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Rajaraman, V. 2012. History of Computing in India 1955-2010. Bangalore: IEEE Computer Society History Committee.

Sambrani, Chaitanya. 2004. “Printing across borders: the Aar-Paar Project.” The Fifth Australian Print Symposium, National Gallery of Australia. Canberra.

Samdanis, Marios. 2016. “The Impact of New Technology on Art.” In Art Business Today : 20 Key Topics, by M. (2016)J. Hackforth-Jones Samdanis and I. Robertson, 164-172. London: Lund Humphries.

Scaria, Gigi, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Sen, Mithu, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

Singh, Aditi, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (October).

Sussman, Anna Louie. 2017. Artsy by ArtNet. 22 August. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-industries-drive-art-market.

Thukral, Jiten, and Sumir Tagra, interview by Shaleen Wadhwana. 2019. Impact of Technology on Art Practises at the Turn of the 21st Century in India (September).

[1] Refer to Printing across borders: the Aar-Paar Project by Chaitanya Sambrani, presented at the Fifth Australian Print Symposium, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2004

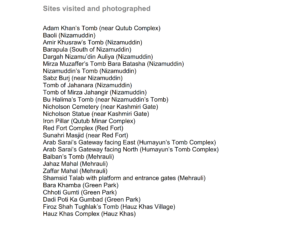

Appendix: List of physical sites and databases compiled as part of Reena Saini Kallat’s research.

About The Author

Shaleen Wadhwana has woven her academic and professional life extensively around the arts and heritage sector. Along with degrees in BA History (Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi) and MA Art History (SOAS, London), she has academic expertise in Art Appreciation (National Museum Institute, Delhi), was awarded the Scholarship of Excellence for Cultural Heritage Law (University of Geneva) and is a Young India Fellow (Ashoka University). She has presented her academic research on embedded histories in objects looted during the 1857 Great Uprising at University College London, England as well as on the repatriation politics surrounding the Kohinoor Diamond at India’s first Art Laws Conference, at the Piramal Learning University, Mumbai.

She has worked at museums and galleries ranging from the Heritage Transport Museum, Haryana to Chemould Prescott Road Gallery, Mumbai. Shaleen curates art and heritage based experiences for a wide spectrum of audiences ranging from universities like Michigan and Harvard to NGOs like Slam Out Loud and institutions like the Tribal Development Board of the Govt. of Maharashtra and Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER). Currently, a visiting faculty at the Design Management Department of MITID Institute of Design in Pune, Shaleen is also the Humanities curriculum designer for the MITID Innovation programme. OSMOSIS, a contemporary art group show which was on display at TARQ Gallery in Mumbai, marks the beginning of her curatorial journey, the idea of which was born in her classroom in Pune. Her recently co-authored article about the impact of the Lodi Art District on the community around it, for the Ministry of External Affairs of India, has been published in India Perspectives, its widely read international e-journal.

An Archaeology of Silence: The Aniconic worlds of Mrinalini Mukherjee

“Our job is to make the Anthropocene as short/thin as possible and to cultivate with each other in every way imaginable epochs to come that can replenish refuge”.

— Donna Haraway, “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin”, Environmental Humanities

“But there is another reason why, from the writer’s point of view, it would serve no purpose to approach them in that way: because to treat them as magical or surreal would be to rob them of precisely the quality that makes them so urgently compelling—which is that they are actually happening on this earth, at this time”.

— Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement

The recently concluded retrospective on Mrinalini Mukherjee at the Met Breuer has revived dormant debates: Was Mukherjee isolated or cosmopolitan?; Is this elevation of craft to high art, tapestries to sculptures? Scholarship by Tania Guha, Victoria Lynn and Grant Watson has explored how such conceptual dichotomies are ill-suited to understanding Mukherjee’s labour, which reveals a deliberate dialectics of thought and form.

Given the retrospective and the accompanied attention to Mukherjee’s practice has coincided with the articulation of substantive civic concern with climate change—it is tempting to ask if the works present ways of thinking on urgent questions of ecology and the state of our planetary futures. This essay is concerned as much with the formal content of Mukherjee’s art as with the question of what it means to engage with these works amidst a growing public discourse on climate change.

In the essay “Indian Roots for a Universal Idiom”Ahuja sieves through Mukherjee’s personal archive to present a photographic record of her visits across India and Southeast Asia, to temples and other sites of worship in ancient settlements, such as Hampi, Mahabalipuram, Ajanta and Ellora, Sitaranasal, Konark, Bhubaneswar. Mukherjee’s husband recorded the intricate facades of stone temples; figures of Nagas, Yakshis, Mithunas and Apsaras; and aniconic structures situated in the wild. The presence of foliage in these structures is regarded as intrinsic to the divinity of the site, and not viewed as encroachment or adornment. To Ahuja, the foliage and the structure are inextricable—the carvings and sculptures “emerge” from and are enframed by the vegetal expanse. He argues that through the rigorous documentation of the pastoral via photographic slides, and the production of three-dimensional sculptures that mimic the relief work on temple facades, Mukherjee is practicing “both an ethno-archaeology and a landscape archaeology in the contemporary”. This reading can be extended further to consider, does Mukherjee’s work and archive permit us to rethink the meaning of landscape itself?

Landscapes have traditionally been defined in a visual-representational plane, always accessed through the subjectivity of human presence. As much as landscapes have been viewed as mediated through the psyche, or in turn formative of human experience, in the study of art and photography it has been understood as inert—so much as the absence of human subjects is viewed as the reduction of pictorial function to a descriptive register that could be empty, or still. Landscapes exist as the domain of cultural and political practice, for W J T Mitchell, they are sites of power—and he has argued to shift the understanding of landscape from “a noun to a verb”.4 Mitchell states that the propagation of the contemplative gaze of the unencumbered subject of modernity has worked to conceal the imperial and industrial influence on the natural imagination from the early nineteenth century, where expeditions and excursions became symbols of annexation. As Karen Barad notes, our understanding of landscape as context for human activity has fundamentally shaped disciplinary tenets. She argues that “matter” is not, in fact, “little bits of nature, or a blank slate, surface, or site passively awaiting signification, nor is it an uncontested ground for scientific, feminist, or Marxist theories. Matter is not immutable or passive. Nor is it a fixed support, location, referent, or source of sustainability for discourse”.5 To view the matter as active beyond the human, driven as much by the biotic as the abiotic, is to think of the scalar impact of the Anthropocene, a period of intense human activity in the form of industrial and post-industrial processes, has propelled the extinction of landscapes, species and processes that may be difficult to revive.

Notes

- Jhaveri notes how Mukherjee’s selection of the ubiquitous material such as natural ropes, was a highly unusual gesture, appended by her refusal of traditional looms in favour of provisional frames and armatures. Mrinalini Mukherjee, eds. Shanay Jhaveri and Grant Watson (Shoestring Publishers, 2019).

- Naman Ahuja, “Indian Roots for a Universal Idiom, ” in Mrinalini Mukherjee, eds. Shanay Jhaveri and Grant Watson (Shoestring Publishers, 2019).

- Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (New York: Routledge, 2013), 2.

- W J T Mitchell, Landscape and Power (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 1.

- Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007), 151.

- David Farrier and Aeon, “The Concept of Deep Time is Changing,” The Atlantic, October 31, 2016, URL: Click Here

About The Author

Archive Fever: From Celluloid to Digital Body

The silver screen—from the liquidated remains of the celluloid of cinema’s past—beckons us to consider the archival form through a slew of concerns that inform related fields of art and conservation. Celluloid film was the original vessel for photography and cinema; a living, breathing medium—one that deteriorates with every viewing.

Celluloid is almost organic through its wear, similar to an aging body. This decay is familiar to us, in how it mirrors the human condition of an omnipresent interplay between life and death, use and futility. Paradoxically, it is decay that determines how we assign the organic. Melting celluloid into silver was a common enough practice in India, since the 60s and 70s, which is telling in how we have valued our filmic, and ultimately, artistic and cultural heritage—from industry to institution.

The traditional form of the archive involves the imposition of overriding structures and systems of classification for organisation and ultimately, knowledge production. The archive seeks to be external to the object-form. However, there is an existential crisis, inextricably linked to the form of the archive; by its very nature the archive is self-defeating to its purpose, as it seeks to document experience(s) of the whole, to represent. French deconstructionist Jacques Derrida posited the archive as fueled and sustained, by the death drive, the Freudian bug that exists within nature and the human psyche, of the destructive drive to return to a state before the fact of birth. Vice versa, the death drive is said to be anarchic and refusing archivisation, inducing forgetfulness, gaps in memory and ultimately, destruction of its own traces—according to Derrida, it “devours it even before producing it on the outside”, a constant tension concurrent.

Derrida says that the consequence of the need for an external for an archive to exist, is “what permits and conditions archivisation” is that we will “never find anything other than what exposes to destruction.” There, the archive only works against itself.

Observed through the finitudes we experience and perceive, creates the archival impulse. Derrida characterised the archival impulse as a “fever” or perhaps more accurately, “feverish”, to express the erratic energy, a compulsivity, that directs itself towards achieving a “completeness”, to command and structure, and ultimately consume, by defining the whole.

Walter Benjamin spoke of a “foreboding” of an age where the impulse to collect only grows expontentially. The digital as form is a priori, in and of itself, an archival form–self-referential in nature. This in itself becomes the ultimate archival form in one sense, where it is alive as a repository and an interpretive space, that film scholar, Ashish Rajadhyaksha posits as the archive.

The digital form is seen as the truly archival image, according to cultural theorist, Okwui Enweazor. The digital file and form is its own archivisation, not relying on an external, i.e. separate from itself. With the fact of digital bootlegging, the digital file constantly undergoes replication and decentralised distribution, from institute/company to a worldwide userbase. The digital file exists in the multiples, against the singular source in analogue, and distribution networks are such that they are difficult to wipe out, being replicated ad infinitum. This becomes an interesting dimension, as it essentially has the capacity to resuscitate lost and endangered film material. Benjamin, in his canonical text “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, emphasises the shift through the reproducible image, as not only technical or indexical, but temporal. This is where I propose the consideration of the digital file as cyborg body—one that corrupts at random and is aligned with the chaos of the inorganic. The digital can be endlessly replicated in theory, not requiring re-production. The almost primitive nature of digital distribution challenges and circumvents established channels of distribution in the “material” aspect, and the very form of the archive itself.

With the digital age, came the subsequent decentralisation of information, and subsequently film, creating networks of peer-to-peer sharing and communities that rallied to archive. This was easier to achieve in the digital form through torrenting, online streaming, peer-to-peer filesharing (remember MediaFire?) and other forms of digital bootlegging and hoarding. The early 2000s to mid-2010s was the era of digital accumulation. This was until the final blow to the global network of web piracy, in 2014, when the PirateBay headquarters, and subsequently other major sites were raided and servers seized.

These forms of dissemination allowed for rich repositories – personal in form – and restricted to thousands of hard drives across the world – a strange digital utopia. Of especially music and film, they served well especially, previously having been bound tightly by the distribution channels. Now through platforms like Mubi and Criterion Channel are now building archives of restored and rare films, for past and contemporary, though again limited by distribution channels and licenses—titles vary from country to country.

Preservation of films in the Indian context shows us a haphazard body of uneven preservation and conservation, where value is not met with the archival impulse. Beyond institutionalisation of our collective cinematic body, beyond internationally recognised directors like Satyajit Ray and Mani Kaul (whose films have been painstakingly restored, but at the same time, original material has faced decay and loss) and Bollywood, how do we keep attempts to preserve and circulate film alive? The Bazaar method of conservation refers to the material, unstructured, unorganised systems of circulation that exist in a decentralised form, which Rajadhyaksha talks about. He mentions the original print of Kannada actor Rajkumar’s first film Bedara Kannappa, that was thought to be lost, but was eventually found being regularly screened at a temple in Old Delhi, with the copy attained from Chor Bazaar. This seemingly antithetical form of conservation, that takes from the un-organised modes of circulation and eventual discard, presents a chaotic, almost anarchic form of consumption outside of the institutional space. These are fugitive responses to national and subsequently global knowledge suprastructures.

The Bazaar Conservation method, as termed by Rajadhyaksha, subverts the singularity of authorial intention in film conservation strategy. As with the expensive process of digitisation, there are constant questions that arise of value and the “canon” in Indian (and to extend, world) cinema, and the parameters to be drawn around what is to be salvaged for future generations and cultural history at large, and what we can “allow” to deteriorate and eventually disappear. The English word “archive” is traced to have been in use from early 17th century onwards, but its verb form has only been dated back to the late 19th century, which could lend an insight into the evolving form of the archive, and our conception of it, from simply meaning “public” or government records. Rajadhyaksha speaks of the archive not only as a repository, but also an “interpreative space”, i.e. a site for the production of knowledge.

The late PK Nair, obsessive film archivist and former director of National Film Archives of India, Pune, shared an anecdote in the documentary film Celluloid Man, of instances where Russian films, celluloid at the time, would be sent to the NFAI in exchange for Indian films the reel cases harbouring secret exchanges between the institutes and countries, a fugitive strategy of conservation, beyond established international (and legal) systems of trade. He would be fondly remembered by students at FTII for the open screenings, where he’d freely show films from the archive. This is commendable in relation to what Rajadhyaksha says about the Bazaar method. Beyond this, he is said to have singlehandedly spearheaded the mission of Indian film conservation at NFAI (to the extent of seemingly disrupting his own private life at times). Such strategies in play produce disruptions to the organising systems of power. In the digital age, the figure of the collector and archivist is shifting—presenting a “chaos of memories” in unorganised collections over several hard drives, as P.P Sneha, digital humanities scholar, writes.

In contrast, “prearchiving” in anticipation, according to Derrida, becomes an archival violence, where overriding structures are imposed, falsely, beforehand. This is opposed to “allowing” the archive to grow “organically”, unorganised. This is where he draws on notions of archival violence. The pre-emptive nature of this imposes an institutional violence in a underlying expectation of hierarchical considerations. The archival problem arises here—where does the outside (of the archive) commence?

The fast-evolving nature of technologies, paired with their past forced obsolescence, made the format of video up until the digital, unreliable. Problems range from preservation of analogue material that already exists, to interpreting, tagging, categorising and allocating other forms of signifiers so as to assure a future of the organised digital archive. Another problem being battled is the exponential increase in storage required for a present that is digitally conscious/self-aware. Archival digital material also needs to be in good condition in order to assure good digital copies that will continue to mark the file(s).

Even with the digital, we lament the quick random deaths of files, vastly different from the wear and tear of the celluloid body, to a erratic, random corruption of files. This chaotic impulse of the digital to destroy itself, so to speak, can be seen in comparison to the preservation of celluloid and other analogue forms of data storage. Digital film also needs constant restoration wherein there lies the problem of expense, again, along with suitable knowledge, skill, and strategies in consignation.

The Getty Research Institute uses a digital preservation software, that generates a “checksum”, which they compare to a fingerprint of a file, or a unique code, where a numerical value is assigned based on the weight of the file, which they intermittently use to compare and generate constantly, to prevent from decay, and restore from a backup copy. Though the backup copy is an infinite archival process as well, backup copies distributed across various servers hints at some hope.

The route to conservation and preservation lies outside of the institutional superstructures of knowledge-to-peer is a radical shift from the global scale of things, where the “local” becomes the antidote.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

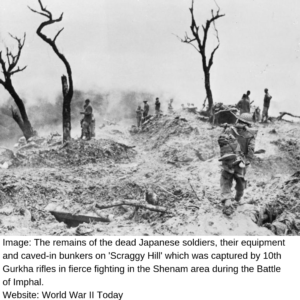

REQUIEM FOR THE FUTURE

In May 1942, Japan dropped the first bomb on Imphal, the capital of the then Princely state of Manipur. The second bomb followed within the week. The Allied British campaign against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan was bolstered by the military, industrial and financial facilitation provided by colonized India.1 The subcontinent served as a base for American operations in support of China, both Allied Nations as well. The Second World War—which was accompanied by heinous events like the Holocaust, orchestrated famines and the novelty of nuclear weapons in combat—resulted in the defeat of the Axis powers and marked the beginning of the Atomic Age.

While the residents of Imphal were fleeing their homes, refugees from Japanese-conquered Burma and the retreating soldiers of the British Indian Army were streaming through Manipur en route to Dimapur and Silchar, in what comprised the territory of Assam then. Imphal, being on the frontline of the British-colonised India and the Japanese-colonised Burma, found itself in a precarious predicament. It witnessed a surge in construction of airfields and army bases by the Allies who claimed air superiority in the Burma Theater. After the area was completely cut-off by land, the Allies used their privilege to provide supplies to their troops by air for months on end, while the Japanese soldiers stranded in the area gradually perished. The Battle of Imphal and the Battle of Kohima became turning points in the “South-East Asian Theater of World War II” and the campaign against the Allied Forces. The Japanese Army, which had formed a minor alliance with the Azad Hind Fauj or the Indian National Army under Subhash Chandra Bose, planned on conquering the Indian mainland and cutting off the supply route to China. This mission was named “Operation U-Go.” But the relentless monsoon proved to be a hindrance in the replenishment of supplies, forestalling the Japanese attack. The consequent starvation resulted in the Japanese defeat by the British Indian Army. Had the operation succeeded, the Allies would have faced a devastating blow and history would have taken a different route towards the present day.

Notes

- Auriol Weigold, Churchill, Roosevelt and India: Propaganda During World War II (London: Routledge, 2008).

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), “Imphal and Kohima,” CWGC Online Archives, URL: https://www.cwgc.org/history-and-archives/second-world-war/campaigns/war-in-the-east/imphal-and-kohima.

- Nuclear Engergy Institute, “Chernobyl accidents and its consequences,” NEI Factsheet, May 2019, URL: https://www.nei.org/resources/fact-sheets/chernobyl-accident-and-its-consequences.

- David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth: A story of the future (London: Allen Lane, 2019).

About The Author

The Mythos of Artificial Intelligence

Where was the line going to be drawn between the sacred and the god-given as separate from the artifice, the mechanical, and the man-made, these early scientific minds would come to wonder. A crucial debate today runs along those lines, and is perhaps approached with far more trepidation, and that is within the ethics of AI; the dangers that it may pose, with doyens in the field like Elon Musk raising an alarm. It makes one wonder whether this is the first time that these issues of giving power to AI in the form of consciousness have risen, did the early thinkers and inventors not consider the potential both positive and negative, and if they did what was their approach in coming to terms with it.

It is helpful to consider the spirit of the Renaissance period, where a deeply ingrained ideal of what drives creation was this notion of the divine and the muses, as is explored in Elizabeth Gilbert’s Big Magic. These external entities were believed by many to be the source of their genius, and in having that external impetus behind these extraordinary inventions of artifices, it was perhaps easy to shoulder the responsibility that came with creating them. It made carrying the existential burden of giving machines and man-made inventions a consciousness, and creating something which one day may very well be beyond human control, not that urgent of an issue. Therefore, in that invigorating environment of scientific and creative temper, these mechanical innovations, the early AI experimentations (so to speak), became a medium for humanity to connect with the divine, with the universe, and with the very laws that founded the basis of human existence. Medieval automata gave those early thinkers the ultimate field of creation through which we could explain our own bodies and their relationship with our environments, forming the pillars of natural philosophy and paving the way for what we would come to develop as modern science.

Interestingly enough the Oxford Dictionary’s definition of the robot, a mechanical invention, is demarcated into two definitions. The first explicitly belongs to the realm of science fiction or scientific romances as they were once known and is something along the lines of, “a machine resembling a human being and able to replicate certain human movements and functions automatically.” Then there is the second definition which is meant for greater real-world application and states, “A machine capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically, especially one programmable by a computer”. It is a fascinating line of distinction drawn between these two remarkably similar definitions. The one of fictional realms is shockingly rudimentary and somewhat primitive, almost begging for an update, a surprising fact when one considers just how far the imagination and wonder in the realms of science fiction has been a precursor to reality. The process of creation begins from idea to thought-process to realisation to execution, and time and time again these ideas have germinated within the creative space of the human consciousness. This human consciousness which was built upon cultural myths, a collective of stories encapsulating the entirety of the human experience which historically imagined what a world driven by machines and AI technology would look like.

About The Author

WRITE | ART | CONNECT

Ex Natura July – October 2019

In 2010, Rohini Devasher stood atop Mount Saraswati to peer into an infinite cosmos at the Indian Astronomical Observatory in Ladakh. Devasher’s journey to significant astronomical sites was part of her artistic investigation into the world above the stratosphere, and the communities on ground—amateur and expert—that study it. Using varied techniques, artists in Southeast Asia are exploring lifeworlds that lie beyond the naked eye, and simultaneously, engaging with popular ideas of evolution, ecology, and difference.

The early concomitance of art with new technologies in shaping the visual representation of the physical world has been well-documented, from the detailed illustrations of plant cells in Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665) to Edward Whymper’s engraving of a mountaineering feat in the Ascent of the Rothorn (1871). Art has served a descriptive function, constructing detailed pictorial representations of natural phenomenon that aspired to depict the ‘real’ with utmost accuracy, a narrative function, enforcing the foundations of modernity, science, and progress, and an evidentiary function, reinforcing the factuality of science.

Artists have also turned a critical gaze to this function of recording—questioning the objectivity ascribed to visual representations. Artists practicing in Southeast Asia have used various mediums to explore these developments, and interpret the natural world. Rejecting a dominantly visual apperception, artists are building poly-sensuous experiences that seek to capture the many ways we feel, think, inhabit and relate to the physical world. Performance and new media installation are bringing forth the political and social processes which shape collective beliefs about technological development. Their practices build new material conventions—drawing from elements and phenomenon such as wind, rain, fossil, and fire—and explore processes of birth and decay hidden in deep, geological time, unraveling the structures and forms which shape the physical and the digital world. The rise of robotic and algorithmic art incorporating artificial intelligence, posits the vision of a post-human horizon, where the organic and the machinic morph and mutate into cyborgic/algorithmic art.

For the upcoming issue of Write Art Connect: Ex Natura, we invite submissions that probe what resides in the interstices of art, technology, and science. We understand technology to imply both pre-analogous and digital, to emergent modes, and welcome writings on various lines of enquiry drawing from disciplines across performance, visual, culinary, video, and film arts. Please submit brief outlines not exceeding 200 words to [email protected] latest by 31 May 2019.

Genetic Drift – SYMBIONT II Cavum Oris Plantae (Mouth Plant) (detail)

Colour pencil, pan pastel, acrylic paint, charcoal, dry pastel, print on vinyl, on wall, 33.5 x 12.8 feet, 2018

Image credit Anil Rane, courtesy the artist and Project 88, Mumbai

LOGIN to see more

To see all the content we have to offer, login below

OR

Don't have an account?

REGISTER FOR FREE

REGISTER FOR FREE

Registration is completely free, stay connected to Serendipity Arts