What Does It Mean

To Make Disappearing Images

In a Disappearing World?

On Anuja Dasgupta’s anthotypes

and the aesthetics of ecological fragility

AUTHOR

Drishya

In the visual economies of the ongoing climate crisis, the domain of photography is often concerned with documenting evidence of our environmental degradation. Satellite images record and archive planetary climate change, both in real-time and over vast timescales. Aestheticized infographics about extreme weather events and ecological disasters circulate endlessly on the internet, offering both data and doom narratives of our impending climate dystopias. This seems futile in the face of widespread environmental apathy and its slow decline in the anthropocene. What if, in the face of this seemingly inevitable, unstoppable, and inescapable environmental collapse, photographs were to embody the condition of the climate crisis rather than document its after-effects? What if the act of fading was not a failure of the form, but a philosophical position that aligned with the lived realities of the climate collapse?

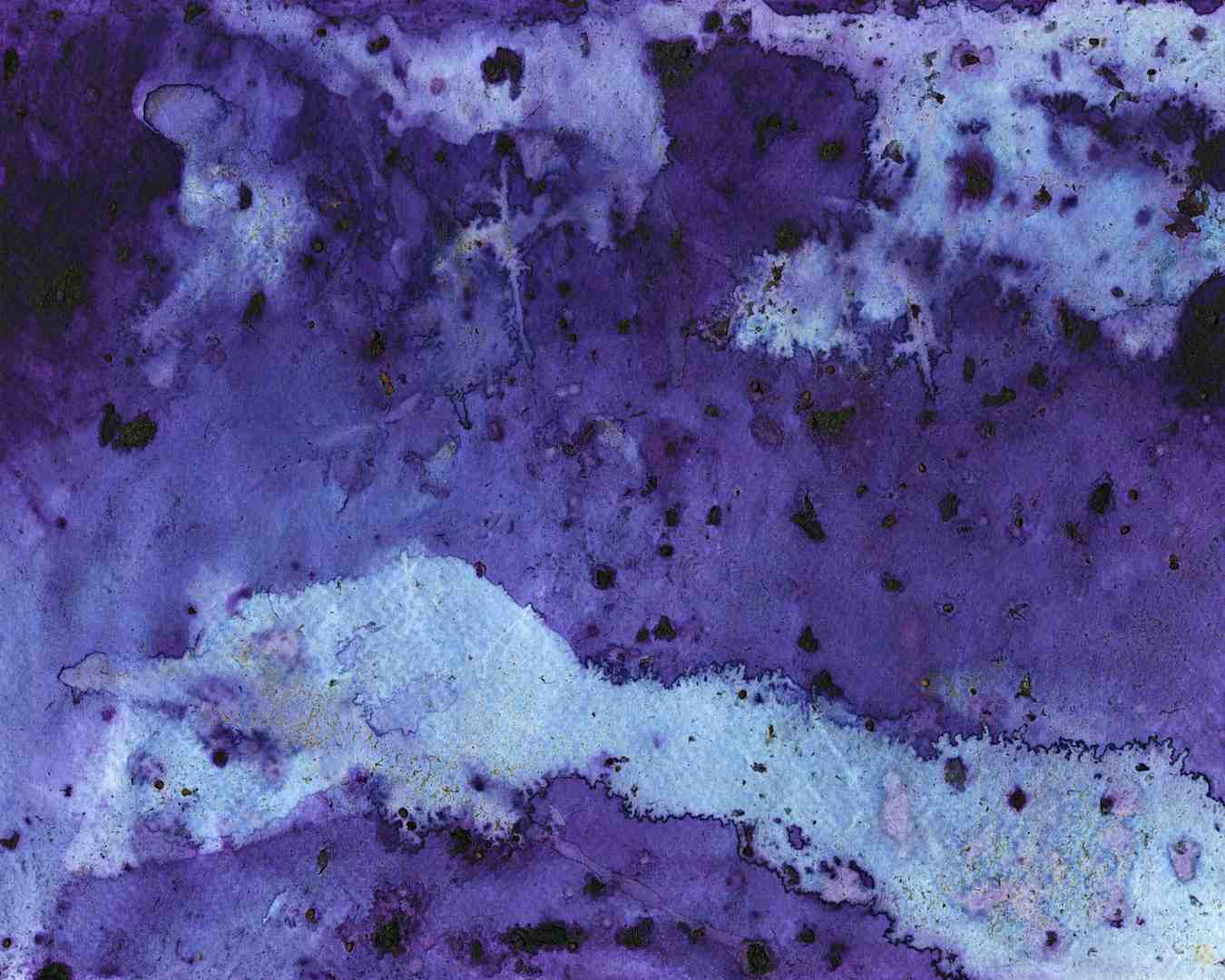

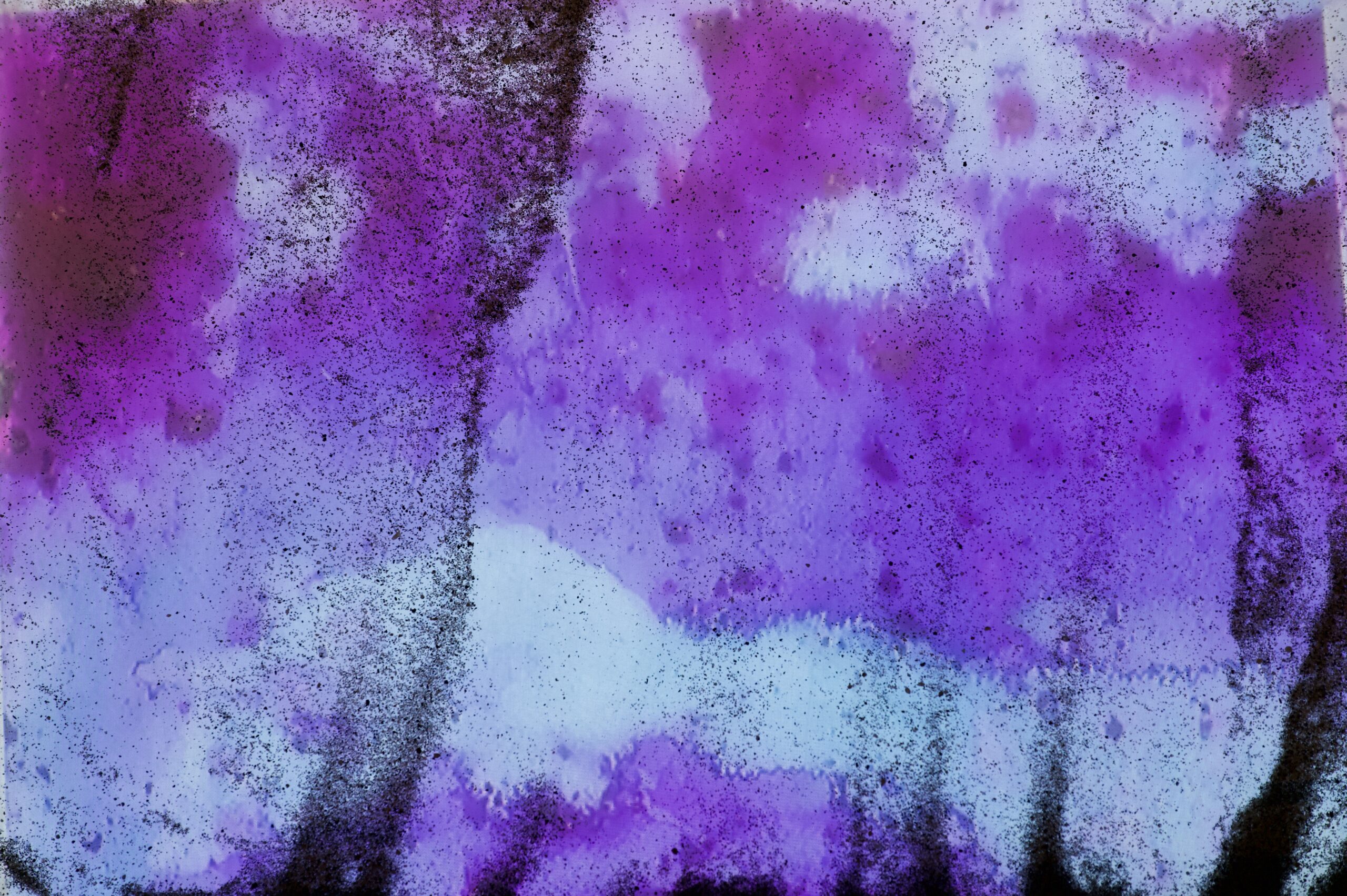

These are the questions that lay the foundation for the work of visual artist Anuja Dasgupta. Dasgupta’s camera-less photographs resist the permanence and precision of conventional photographic media, embracing instead the aesthetics of fragility, decay, and the ephemerality of the natural world. Working primarily with anthotypes—images created with photo-sensitive plant-based pigments and exposed to direct sunlight—Dasgupta responds to the climate crisis by embodying its conditions. When exposed to sunlight, her anthotypes change colour and continue to fade thereafter. This process of fading represents a form of acceptance of the impermanence of the natural world, in her work.

The anthotype process is one of photography’s oldest and most poetic alternative techniques. Invented by the Scottish scientist Mary Somerville in 1845, the anthotype process gets its name from the Greek words ‘anthos’, meaning ‘flower’, and ‘typos’, meaning ‘imprint’. Somerville developed the process as an alternative to Sir John Herschel’s cyanotype process, using photosensitive pigments extracted from fruits, flowers, roots, and other parts of plant bodies instead of a solution of potassium ferricyanide and ferric ammonium citrate to create images. By exposing these plant extracts to different parts of the solar spectrum, Somerville discovered that different spectral exposures produced different colours from the same plant, revealing an alchemical connection between light and life. However, as photography shifted toward commercial and archival ambitions and faster chemical processes such as the daguerreotype and tintype became more popular, the anthotype process—with its fragility, slowness, and impermanence—was relegated to the domain of the more un-urgent photography, in the conventional sense.. Dasgupta’s work reclaims this alternative image-making process as a provocative gesture towards humility and resistance in the anthropocene. By moving away from photographic permanence towards ecological impermanence, she transforms this historic process into a modern aesthetic of resistance.

In ‘Elemental Whispers’ (2022-present), an ongoing body of work created in the trans-Himalayan landscape of Ladakh, where Dasgupta lives and works, she collects fallen leaves, flowers, and wild, uncultivated berries and botanical matter from high-altitude riverbanks and rocky slopes to produce imprints of the delicate Himalayan ecosystems. She pounds these plant materials with a pestle, distils them into photosensitive emulsions, and brushes the emulsion onto sheets of watercolour paper. The coated sheets are then placed at various sites along the Indus River, where sunlight, river drift, birds, insects, and animals leave their marks on the surface. The final image is not a frozen slice of time but what Dasgupta describes as a “meditative pull towards the silent rhythms of natural forces that create, care for, and cast existence on earth.”[1]

Dasgupta’s anthotypes not only resist the camera as an extractive tool but also the conventional photographic medium’s compulsion to fix, preserve, and archive. In Dasgupta’s hands, anthotypes become an alternative mode of seeing that values impermanence, contingency, and collaboration with non-human and more-than-human agents. Dasgupta aligns her practice with the instability of the very ecosystem she lives and works within by allowing her anthotypes to fade — to embody the conditions of the Anthropocene not by depicting its violence, but by rejecting its narrative of control.

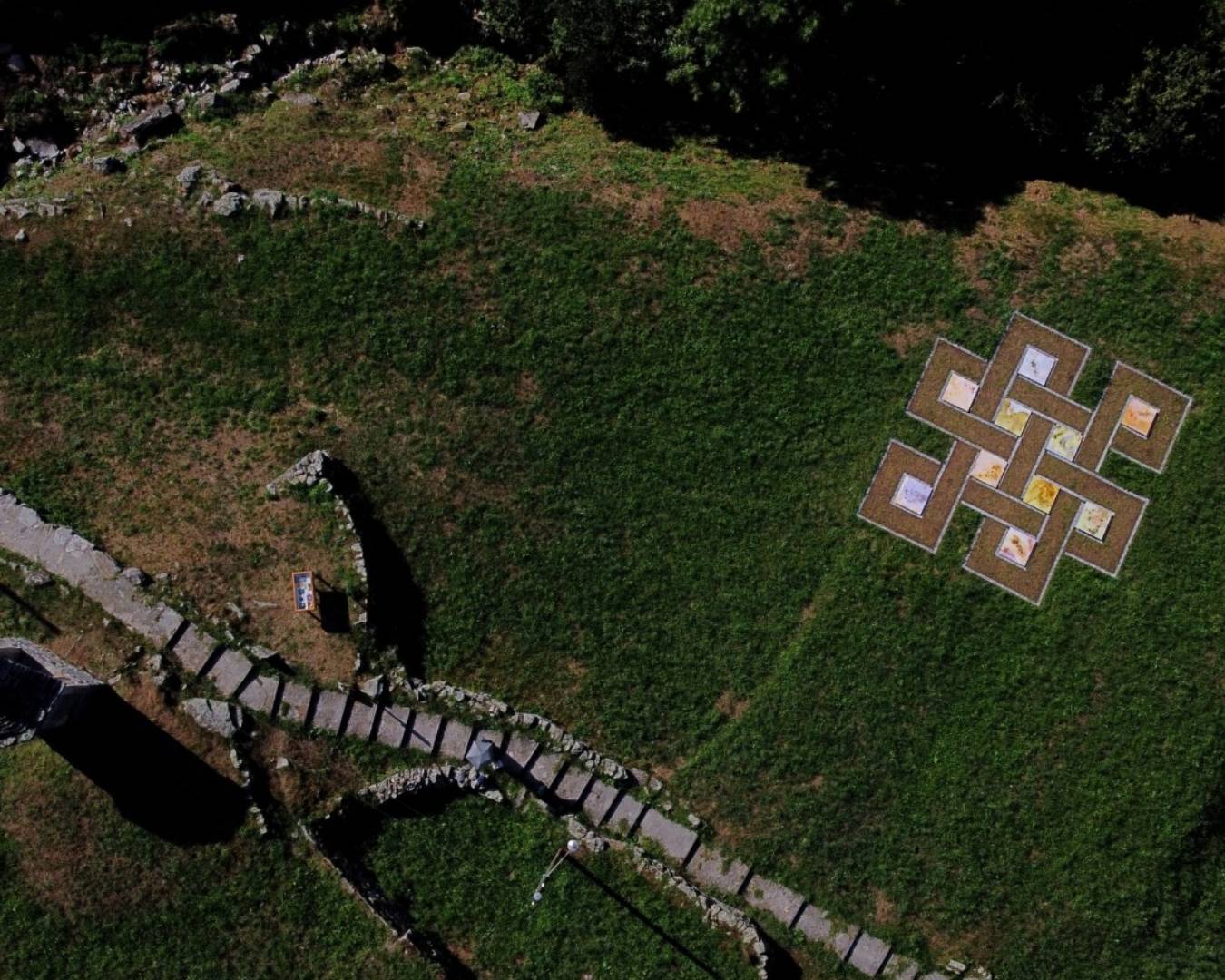

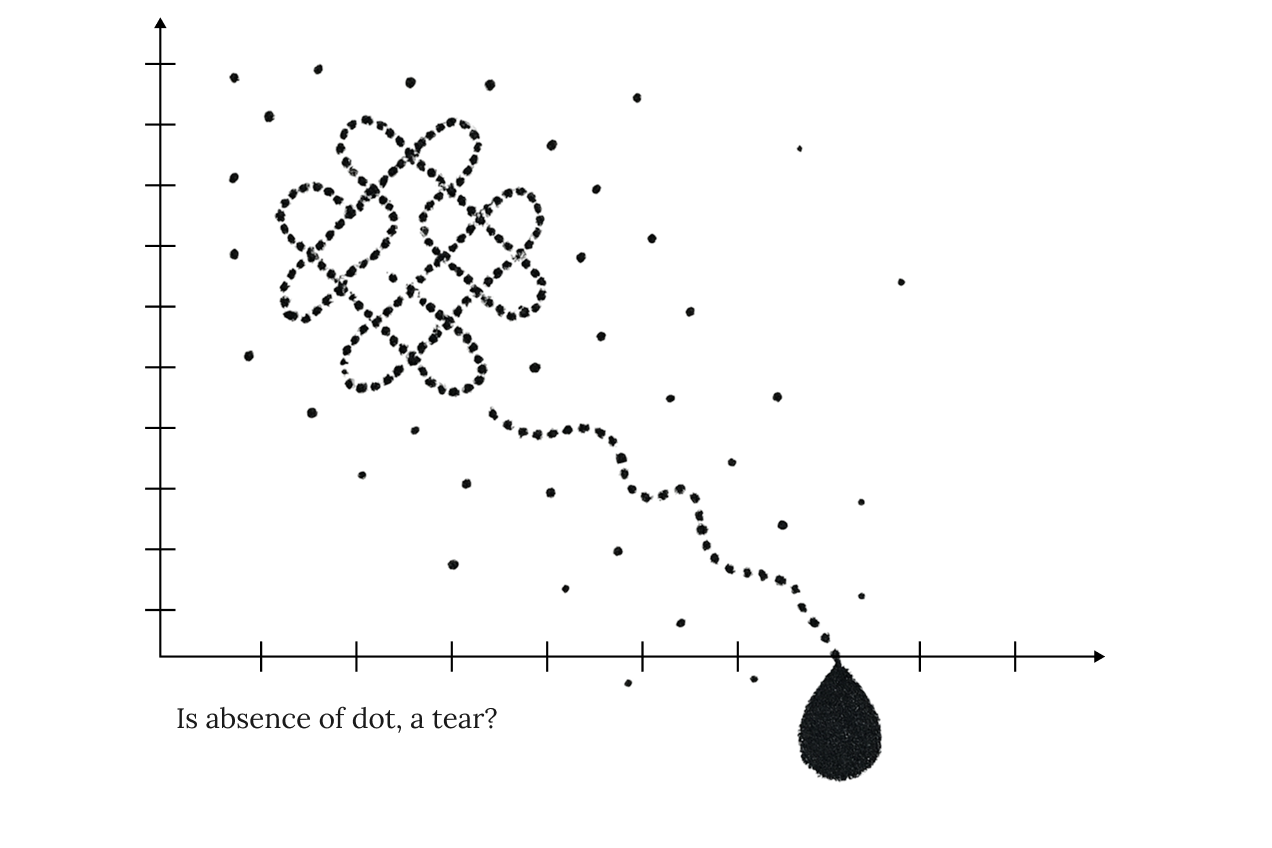

This pursuit continues in ‘How Does a River Breathe?’, a large-scale, site-specific installation of ten anthotypes that Dasgupta produced and staged in the Valle Verzasca, Switzerland, in 2024. Exposed beside the Verzasca River, using the river water as a developer, these images bear the marks of local fauna, flora, and sunlight. In these images, the concept of authorship dissolves and a collaboration between botanical chemistry, spectral light, and the agency of non-human life comes to the fore. Dasgupta installed them outdoors in a trail shaped like the endless knot with an indistinguishable beginning and end — an ancient symbol of continuity and entanglement rooted in trans-Himalayan cultures. Viewers were encouraged to walk this loop, becoming participants in a meditation on the interconnectedness of life, the living, and the lifelines that connect them. In Dasgupta’s words, ‘each viewer becomes a participant in the making of the endless knot: a gentle intersection of trans-Himalayan culture with the Verzasca landscape and a visual composition that echoes the interconnected physiology of the natural world.’[2]

There is also an elegiac undertone to this mode of image-making. As pollinator populations decline and flowering plants evolve to fertilize their seeds with their pollen—an evolutionary phenomenon known as ‘selfing’, which leads to reduced biodiversity and increased vulnerability to disease and environmental stress takes place, and the very life forms that make anthotypes possible become endangered. The disappearing image becomes both a metaphor and a memorial of a vanishing world — a brief collaboration between humans and a non-human world, under threat that the human world poses.

In resisting the extractive tendencies of conventional photography, Dasgupta’s anthotypes propose a radically different mode of seeing — one rooted in a profound recognition of the other, the more-than-human, and the rest of the world. By surrendering authorship to natural processes, Dasgupta critiques extractive visual traditions and de-centres anthropocentric narratives. This act of letting go provides an opportunity for what the British philosopher and novelist Iris Murdoch called ‘unselfing’. In The Sovereignty of Good (1970), Murdoch defined ‘unselfing’ as the practice of de-centring the ego to attend to the world from a place of care. “Goodness is connected with the attempt to see the unself,” Murdoch wrote, “to see and to respond to the real world in the light of a virtuous consciousness.”[3]

In Dasgupta’s work, this act of ‘unselfing’ manifests materially. By surrendering the authorship of the image to natural processes like fading, disintegration, and uncertainty, she enacts a moral and philosophical re-vision: one where humans are no longer the axis along which the world is ordered.

Permanence is not a neutral ambition — within it are encoded fantasies of dominance, preservation, and control. But Dasgupta is not concerned with making permanent images; her practice is about unmaking the assumptions that govern photographic representation. Her ephemeral anthotypes challenge our fantasies of anthropocentrism; they gesture towards resistance against dominant ideas of the anthropocene, extractive seeing, and the image as a form of possession. To look at her work is to see the photographic image as a form of attentiveness rather than assertion. In their slowness, their softness, and their impermanence, Dasgupta’s anthotypes represent a recalibration of what it means to witness environmental change and make disappearing images in a disappearing world.

Notes

- Anuja Dasgupta, Elemental Whispers (2022–Present)

- Anuja Dasgupta, How Does A River Breathe? (2024)

- Iris Murdoch, The Sovereignty of Good (1970)

Wait for Weight: Collective Performance as Resistance

AUTHOR

G. Vignesh

In a time of intensifying ecological collapse—when forests are felled in the name of urban development and the rhetoric of “progress” is weaponised to erode habitats—can art embody resistance? Can art not only mourn loss but also actively halt it?

Wait for Weight, a site-responsive performance by the emerging interdisciplinary action group; Possible Futures, rooted in gesture, endurance, and sonic invocation, has emerged as a tender political intervention—a shared act of grief, resistance, and refusal. This essay frames it within broader dialogues in performance studies, eco-activism, and South Asian resistance histories.

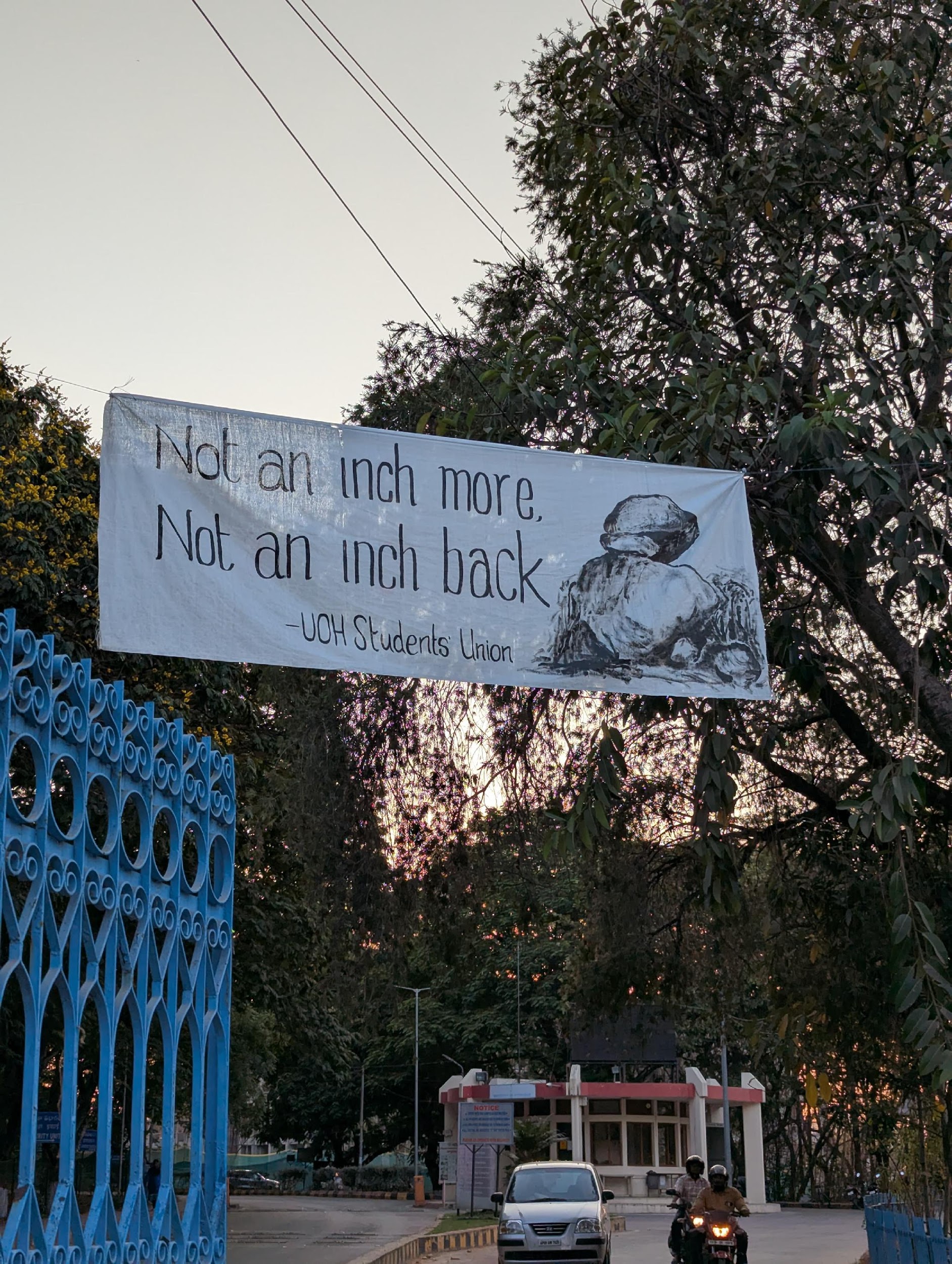

The performance unfolded amid a student-led movement at the University of Hyderabad that successfully halted the auction and deforestation of nearly 400 acres of ecologically significant forest land (see Figure 1). The protests—anchored in solidarity, care, and collective refusal—had already disrupted the narrative of inevitability around ‘development’. Possible Futures chose this moment to create a work that echoed and deepened the call to action. The slogan of the protests—’Hum jungle bachane nikle hain… Aao hamare saath chalo’ (We have come out to save the forest… Come, walk with us)—was not merely a chant, but a living invocation woven into the performance itself.

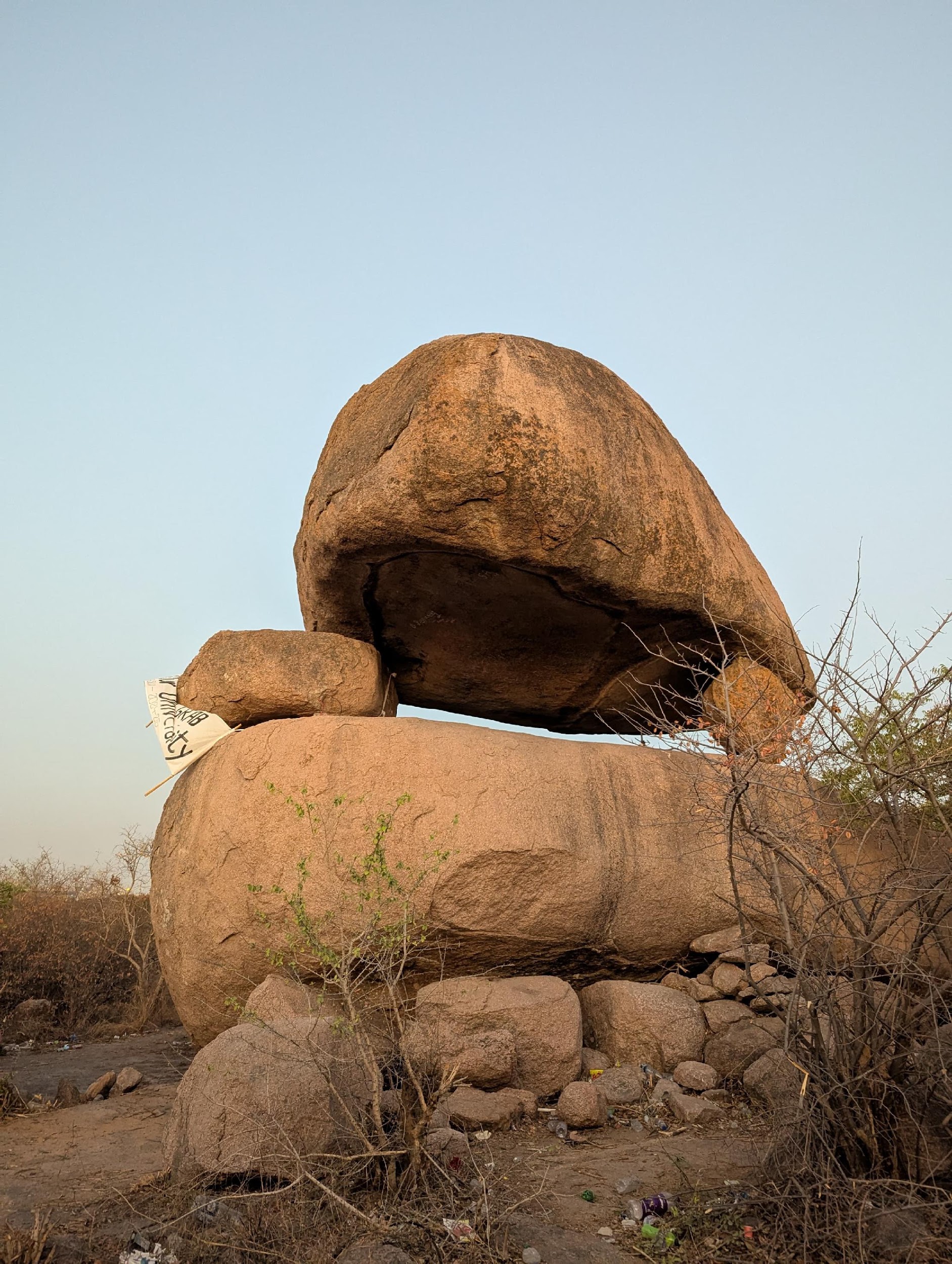

On International Forest Day and the Spring Equinox, Possible Futures gathered at Mushroom Rock—an ancient granite formation and geological icon of the Deccan plateau—as more-than-symbolic ground (see Figure 2).

The date brought together the cosmic and the terrestrial, inviting a ritualistic framework that blurred lines between protest, poetics, and ceremony. Possible Futures—comprising visual artists, theatre practitioners, and students—staged the work not only as witness to ecological grief but also as an embodied continuation of the ongoing resistance.

At Mushroom Rock, the performers invited the site itself into their work. The land, air, and stone became collaborators, framing a dialogue between human and nonhuman presences (see Figure 3). The piece unfolded over an hour, yet its rhythms echoed the slow, patient time of forests and rocks. In this confluence of bodies, material, and sound, the platform asked: what does it mean to carry the weight of preservation? What does resistance feel like—not as ideology alone but as sweat, care, and shared breath?

As Amelia Jones writes, “Performance art demands a reconsideration of presence and embodiment, operating in the space between the material and the ephemeral.” Performance art has long served as a medium for embodied resistance. From the avant-garde confrontations of Dada and Fluxus to Ana Mendieta’s earthworks and Rummana Hussain’s feminist interventions, artists have used the body to speak where words fail. In India, the likes of Inder Salim and Nikhil Chopra have blurred boundaries between identity, endurance, and ecology in site-specific acts.

The central image of the performance was a nest: a giant, hand-woven structure of branches, grass, and roots gathered from the site. This act of making—slow, collaborative, physical—became a living metaphor for refuge, care, and reclamation. The performers enacted distinct yet interconnected gestures of resistance, memory, and care (see Figures 4a–4e): Vignesh traced shadows and imprints of bodies and objects, evoking memory and impermanence. Shivam, shifting between human, bird, and animal, called out with sounds of longing and distress, bridging species. Suresh carried and struck stones until they shattered, conjuring the violence of construction and human labour. Bhanu, wrapped in green construction netting, held a mirror aloft, reflecting and fragmenting the landscape in a quiet question of visibility and erasure. Vishal dragged discarded plastic bottles while singing a Bhojpuri folk song about forests and water, his voice gathering the others into a collective chorus that transcended language and region. Manjari knelt before rocks, whispering to them and arranging them in a quiet ritual of reverence.

At moments, real peacocks—residents of the forest—answered the performers’ calls, merging the boundaries between performer and environment, art and ecology. This “ritual ecology,” as Fern Shaffer and Othello Anderson describe it, attuned the body to threatened landscapes. The nest, fragile yet resilient, stood as a testament to shared participation, responsibility, and the possibility of renewal.

Throughout the performance, Possible Futures resisted the idea of art as detached observation. Instead, they embraced what Paula Serafini describes as “performance action”—a convergence of process-based collective creativity and direct political intervention. In this sense, Wait for Weight was not just a protest performance but also a relational practice that held grief, urgency and hope in equal measure.

As Sonal Khullar notes, “Performance art in India draws from ritual, activism, and public interventions, transforming the body into a site of resistance and renewal.” In this lineage, the performers became both witnesses and agents of change—bearing testimony to what is lost, displaced, or imagined anew.

The political impact of the work extended beyond the site. It became part of the wider student-led movement that successfully halted the proposed auction and deforestation of 400 acres of forest. This continuity between art and activism demonstrates what Serafini calls the “continuity between art and action.” Wait for Weight did not simply respond to the crisis; it intervened.

In the face of relentless development, the platform’s performance served as a reminder; resistance can be quiet, deliberate, and collective. Their presence at Mushroom Rock became more than a moment; it became part of a movement. By the end, what remained was not just the nest atop the rock but the shared memory of bodies moving, bending, and breaking together (see Figure 5-5a). The green netting glimmered in the dusk—not as a shroud of loss but as a sign of conscious intervention. This was art that did not shy away from the political, nor did it sacrifice poetics to protest. It insisted that both are possible—that the body can hold ritual and resistance, care and confrontation, in the same breath.

Echoing the protest slogan—“Hum jungle bachane nikle hain… Aao hamare saath chalo”—Wait for Weight stands as a living call to solidarity. Art does not only bear witness to environmental crises; it intervenes—tenderly, politically, collectively.

- Serafini, Paula. *Performance Action: The Politics of Art Activism*. Routledge, 2018.

- Davidson, Jane Chin. “Performance Art, Performativity, and Environmentalism in the Capitalocene.” *Oxford Research Encyclopedia*, 2019.

- Springett, Selina. “Art-making for Political Ecology: Practice, Poetics and Activism Through Enchantment.” *Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies*, 2021.

- Shaffer, Fern & Anderson, Othello. *Nine-Year Ritual*, 1995–2003.

- Watts, Patricia. “Performative Public Art Ecology.” *ecoartspace*, 2010s.

- Flores, Patrick D. “Difficult Comparisons: The Curatorial Desire for Southeast Asia.” 2008.

- “Chipko Movement.” Wikipedia, accessed July 2025.

- Hindustan Times. “Mourning Has Broken: View Expressions of Ecological Grief From Around the World.” 2022.

- Borasino, Teresa. “Ausangate, a Gaseous Cosmology.” *Framer Framed*, 2023.

- Khullar, Sonal. Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity, and Modernism in India, 1930–1990. University of California Press, 2015.

Grids of Grief: Climate, Caste, and Coastal Memory

AUTHOR

Indhu Kanth

Every grain remembers, each wave forgets…

The sea lives, they say, in rhythms you can almost feel under your skin – a pulse in the breeze, a pattern in the clouds, the subtle pull of tides whispering against your ankles.

For centuries, the Pattinavars1 have tuned their bodies and nets to that pulse: reading the direction of the Vanni and Kota winds2, noting the color of the water. They’ve drawn Kolams3 on thresholds in rice flour to beckon crabs, prawns, and tiny shorebirds. These gestures have been their padu4: a spoken, unspoken code of rotational fishing rights enforced by Oor (village) panchayats with the weight of caste, custom, and collective care.

Recently, I walked the Coromandel Coast at dawn and watched women trace kolam in rice flour across cracked concrete. Minutes later, a fishing trawler’s wake washed it away.

I wondered – can we ever TL;DR this grief, this solastalgia?

Trawlers roar in, engines thrumming through Ennore’s mangrove roots. Steel mills dump slurry into once-clear creeks.

What happens when the very air you lean into to predict tomorrow’s catch becomes synthetic? When the young men who used to lash the catamaran to deep-sea currents trade that timber boat for a day’s wage at the steel plant?

The nets come up empty; the kolam dries to chalky silhouettes.

How do you compress the memory of a disappearing ritual, of lore, of a fish shoal that learned to avoid our nets?

Today, those embodied knowledges lie wounded on the beach like half-buried wrecks. The sea’s pulse is practiced only in memory.

We live in a world that wants coastal wisdom in a tweet and climate collapse in an infographic. And in doing so, we’ve engineered away the very thing that makes us human: the messy, beautiful labor of sitting with loss and longing, of letting the sea and its communities change us from the inside out.

I tried to trace the fractures – not only in the coastline, but in the caste-bound padu, in the ritual economy of welcome, in the porous lines between human and more-than-human life.

I ask: how does art emerge when the sea itself is receding?

How do these dwindling rituals become both archive and act?

Once, the sea was our only teacher…

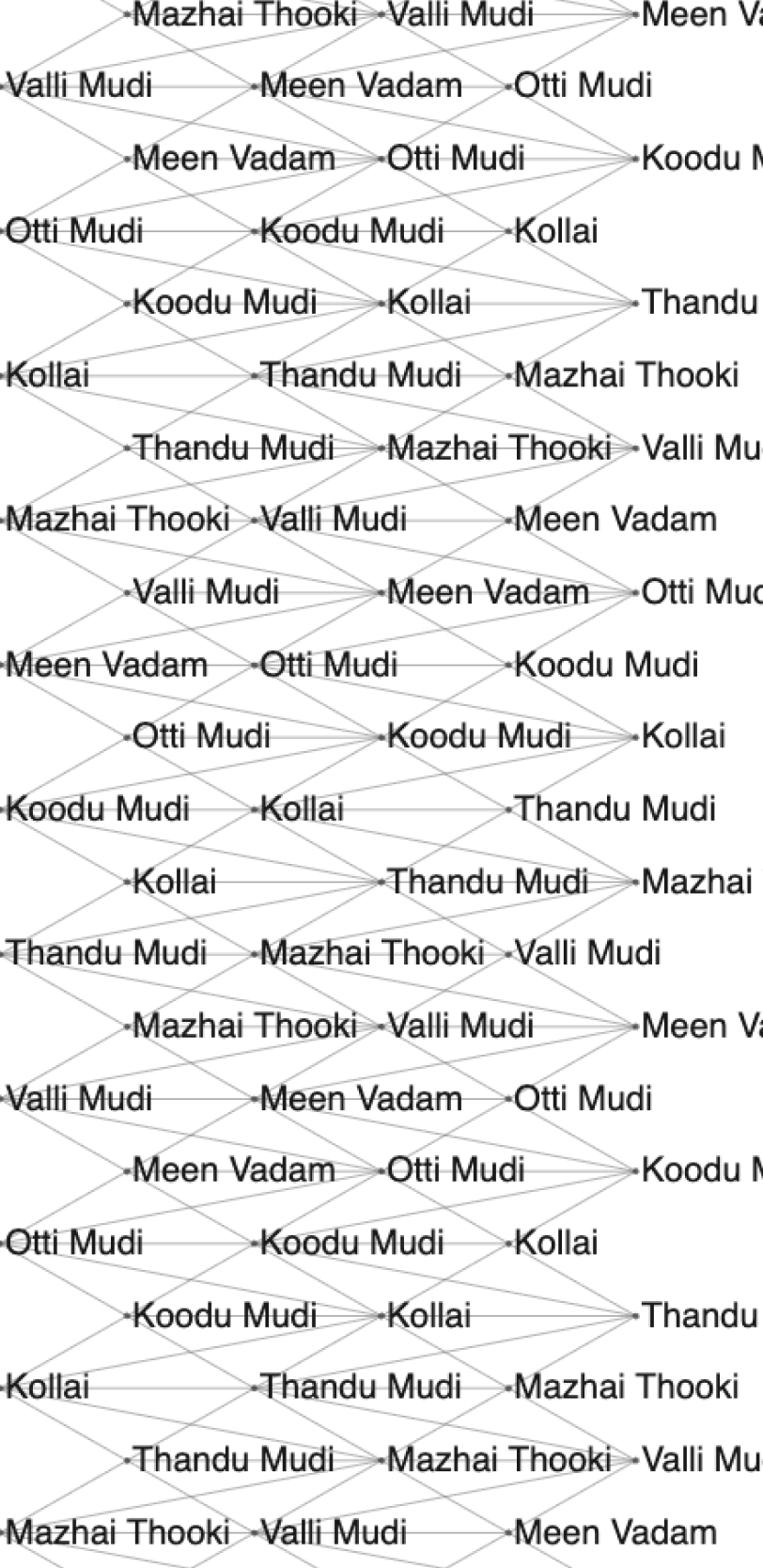

On the Coromandel Coast, a net is more than a net. It is a record of wind direction (vannikai), of sea-current shifts (karai thanni), of fish migrations. Grandmothers had names for every knot (valaichu), every eddy where Garfish (kolameen) gather – teaching grandsons how to plait (kollai) a rope so fine that a single drop of sweat seals the knot.

“You watched the Kota wind rake the water’s surface; you read the Nila jal, that dark blue patch, as a memory of upwelling. You learned that dabjal, the green coconut-water currents, meant lean days ahead.5”

Before fish-finder apps and industrial harbors, the Pattinavars had no choice but to learn the coast’s grammar with their bodies.

“You didn’t grow impatient when your grandfather recited the same fishing saga for the hundredth time, describing tides and moon phases in agonizing detail. You sat cross-legged on the sand because you knew that every telling was both the same and entirely new, shaped by the day’s clouds and your swelling sorrow from the empty nets.6”

Today, we’ve built devices that tell us when valaivicchi (fish schools) pass, then ignore the rituals that taught us to wait, watch, and wonder.

We demand CPUE graphs (catch per unit effort) while the bottom of the ocean pines for its coral.

“My grandmother still tells me how the thalai kattu (the forehead knot) bestowed village membership. I cry every time. Not because the story changes, but because I change. Because each tsunami anniversary, each new chemical spill, makes that story ache differently.7”

But you can’t install empathy like an app update. The waiting, watching, the stammering prayers to Neelatchiamman (Goddess) – that’s their teaching.

Remember when caste was a covenant…

Oor panchayats once wove caste, custom, and care into padu – the rotational fishing rights that kept no one hungry or greedy. The chief’s word was law, but ritual tempered power: fines for chopping mangroves, social ostracism for selling nets to trawlers.

After the 2004 tsunami, those panchayats reactivated padu to allocate relief boats and nets. But the social cracks ran deep.

Mechanized-boat owners – often upwardly mobile Chettiars8 – dominated aid distribution. Widows and Pangali9 families from the lowest rungs got dusty packages, told to wait twelve months. Ostracism hovered beneath speeches about equity.

Youth left for factory jobs. Panchayat meetings emptied. Their rituals went into hiding.

At dawn, women no longer trace kolam in rice flour. Now kolam blooms in acrylics: hard, ornamental, uninviting. Even sacred birds know better than to land.

Communities gather on the strand, tethered to memory, praying to Mariyal (gods of fire and water).They trace symbols in broken rice flour and weep.

These tears aren’t data points. They’re maps with no legend.

Tell me you “get” that, and I’ll ask you to chart the agony of seeing a well or pond dry in April.

And so we drew our grief on walls…

Art on this coast is sprayed on seawalls that crack in the monsoon. It’s pamphlets showing tsunami photo archives stapled to fishing huts. It’s tiny shrines in broken shells and bits of plastic. Out of these fractures, a new canvas emerges.

It is not white-walled nor well-lit; it is sand-dusted and waterlogged. These works embody spatial and emotional metaphors of fragmentation. Grids of grief appear in both tactile and digital realms. They demand viewers navigate a fractured visual field – part archive, part action.

Kolam Festivals & Guided Kolam Tours

In many Tamil coastal regions, collaborative kolam festivals invite participants – youth and outsiders alike – to co-create intricate patterns while discussing community histories and local environmental change. A few organizations offer guided tours for visitors to observe and honor such festivals and practices.

Kannagi Nagar Murals (Chennai)

After the 2004 tsunami, the resettlement colony of Kannagi Nagar became known for its large-scale murals. Artists, many from fishing communities or with strong coastal identities, have transformed walls into visual storytelling canvases exploring themes of survival, memory, resilience, and hope after disaster.

Wetlands Celebration (Pulicat)

World Wetlands Day is observed annually as “Pulicat Day,” featuring catamaran races, ecology quizzes, kolam competitions, and folklore performances. These events weave together ecological conservation and cultural memory, and often see fisherwomen and children as lead participants. Over 120 fisherwomen have been empowered through palm-leaf crafts, linking traditional creative labor to environmental protection and new economic pathways.

Speculative Futures: Repair or Rewilding?

This is not romantic nostalgia.

The sea is receding – scientists warn 30 cm by mid-century. Art cannot paper over these wounds. We must practice a “radical remembrance”.

Seeing kolam lines not as pretty motifs but as calls to cross-pollination; Hearing nets not as loss, but as living archives of weather lore. Knowing that every eroded dune holds a caste story, a mangrove prayer, a forbidden padu tale.

What happens when we invert the gaze?

Can we imagine a kolam drawn by drones scattering seed-bombs of mangrove propagules? Or padu enforced by blockchain contracts, granting rotational rights visible on GPS-mapped chairs?

If art is to be resistance, it must dissolve the walls between gallery and gutter, between padu and protest.

We must draw sketches in sand that outlive the tide – by sparking uprootings of institutions, of industrial investments, of extractive mindsets.

But if we refuse to pause – if we never linger with a story for longer than a scroll – we’ll become creatures of surfaces, skimming endlessly yet never drowning in depth.

Unlike the 24‑hour news cycle, the sand in our shoes and the salt in our hair remain. They linger.

Next time you are near a shore, press your feet into that shifting sand.

Feel the pulse. Just pause.

The next time you see kolam, don’t just photograph it. Offer a handful of rice. Stay a while. Let the tide claim your footsteps.

Because that is the real story:

We’re not here to summarize or compress lives, but to live them – in all their blur and beauty, in all their raging seas and ritual lines – until we learn to draw life again.

When the sea is receding, all that remains is what we choose to draw and who we choose to feed.

Notes

- Pattinavars are a maritime Tamil community primarily found along the Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu, India. They are traditionally involved in fishing, seafaring, and trade. The term “Pattinavar” itself means “inhabitant of a port town”.

- The Vanni winds are locally known as seasonal, dry winds associated with the dry season. These winds tend to come from land masses and are hotter and drier. They influence local climate and agricultural cycles but are not as strong or regular as monsoon-driven winds. Kota wind is used regionally to denote strong, seasonal winds that funnel through mountain passes or coastal gaps. These winds can be associated with the monsoons or the transitional periods between them.

- Kolam is a traditional South Indian art, mainly in Tamil Nadu, featuring intricate geometric and curvilinear patterns drawn at home entrances. Made with rice flour, chalk, or colored powders, kolams are believed to invite prosperity, welcome guests and deities, and serve as a ritual offering to non-human life like birds and insects.

- The Padu system is a traditional method used by fishing communities in India, particularly in regions like Pulicat Lake and Vallarpadam Island, to manage access to fishing grounds

- Romayas, 38, second‑generation boatman from Vizhupuram.

- Murugesan, 67, Pattinavar elder of Nagapattinam who still reads tides by hand‑made charts

- Lakshmi, 46, fisherwoman from Cuddalore whose childhood revolved around granddad’s stories.

- A prominent mercantile and banking community from Tamil Nadu, traditionally known for their wealth, business acumen, and social influence. Many Chettiars belong to higher caste groups and are often upwardly mobile, owning mechanized boats and controlling local economic resources.

- A historically marginalized community in Tamil Nadu, often associated with lower caste status and traditional occupations considered “polluting” or outside the mainstream social hierarchy. Pangali families frequently face social exclusion and economic vulnerability.

- Velvizhi, S., Thamizhazhagan, E., Suvitha, D., Mubarak Ali, A., Arokiya Kevikumar, J., Lourdessamy Meleappane, C., & Fish for All Research and Training Centre, M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Poompuhar, Tamil Nadu. (2021). INDIGENOUS TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE OF FISHER FOLKS IN MANAGING THE OCEAN STATE CONDITIONS, WEATHER VARIABLES AND FISH AVAILABILITY – A STUDY FROM TAMIL NADU AND UNION TERRITORY OF PUDUCHERRY [Journal-article]. World Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Science, 7(5), 57–65. https://www.wjpls.org/admin/assets/article_issue/65042021/1619693600.pdf

- Raja, Selvaraju & Rajamanickam, Geetha & Kizhakudan, Shoba & Vivekanandan, E. (2014). Traditional Knowledge among fishers of Coastal Tamil Nadu with special reference to Climate Change. 10.13140/2.1.1195.0722.

- Rathakrishnan, Tr & Ramasubramanian, Muthuramalingam & Anandaraja, Nallusamy & Suganthi, N. & Anitha, S.. (2009). Traditional fishing practices followed by fisher folks of Tamil Nadu. Indian journal of traditional knowledge. 8. 543-547.

- Balasubramanian, G. The Role of Traditional Panchayats in Coastal Fishing Communities in Tamil Nadu, with Special Reference to their Role in Mediating Tsunami Relief and Rehabilitation Contents.

- Muthupandi, Kalaiarasan & Neethiselvan, Neethirajan & Gayathre, Lakshme & Mariappan, Sangaralingam & Ragavan, Velmurugan & Kalidoss, Radhakrishnan. (2024). Indigenous fishing gears of the Pulicat lagoon of Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 23. 583-593. 10.56042/ijtk.v23i6.11830.

- Bavinck, M., Vivekanandan, V. Qualities of self-governance and wellbeing in the fishing communities of northern Tamil Nadu, India – the role of Pattinavar ur panchayats. Maritime Studies 16, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-017-0070-8

- Madhanagopal, Devendraraj & Pattanaik, Sarmistha. (2020). Exploring fishermen’s local knowledge and perceptions in the face of climate change: the case of coastal Tamil Nadu, India. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 22. 3461-3489. 10.1007/s10668-019-00354-z.

- FSS:HEN612 Traditional Ecological Knowledge Systems. https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2011/HEN612/um/26486599/

The Course of a People’s Land

AUTHOR

Satyam Yadav

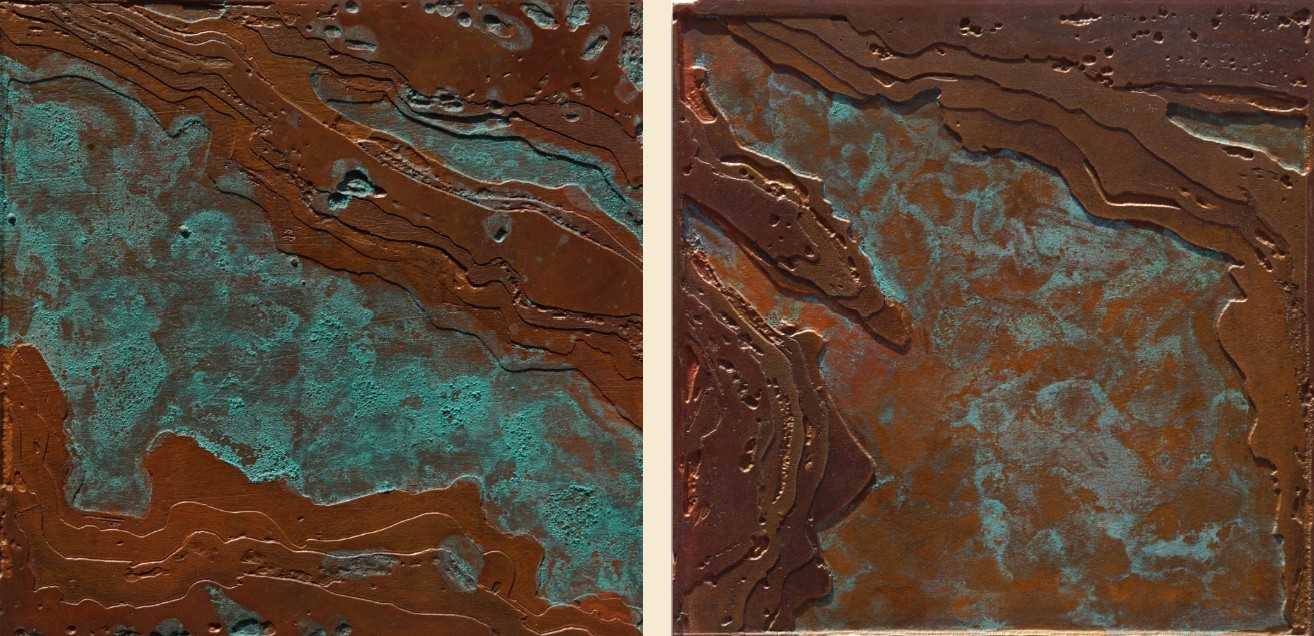

Earlier this year, amidst some exceptional practices on view in a group exhibition at the SOAS Gallery in London,1 I came across a familiar artwork — or a close version of it — that I remembered seeing a long time ago in Delhi. Seemingly an aerial view of an open-pit mining site, each iteration was uniquely reproduced in a grid of about 30 copper plates, mottled with pools of striking blue-green patina filtering out from seams across its metallic surface. Like before, I found myself deeply intrigued by the materiality of the work – not to mention the peculiar rendering of the landscape.

Barren mine sites are a recurring image in artist Sangita Maity’s (b.1989) multimedia practice, which spans photography, photo-etchings, serigraphy, woodcuts, and more. Moving between portraiture and scenes from everyday life, Maity examines how forces of statist extractivism — including mining, hydroelectric projects, and industrial farming — overlap with labour conditions and cultural disembodiment of tribal communities, alongside environmental degradation across the states of Jharkhand, West Bengal and Odisha.

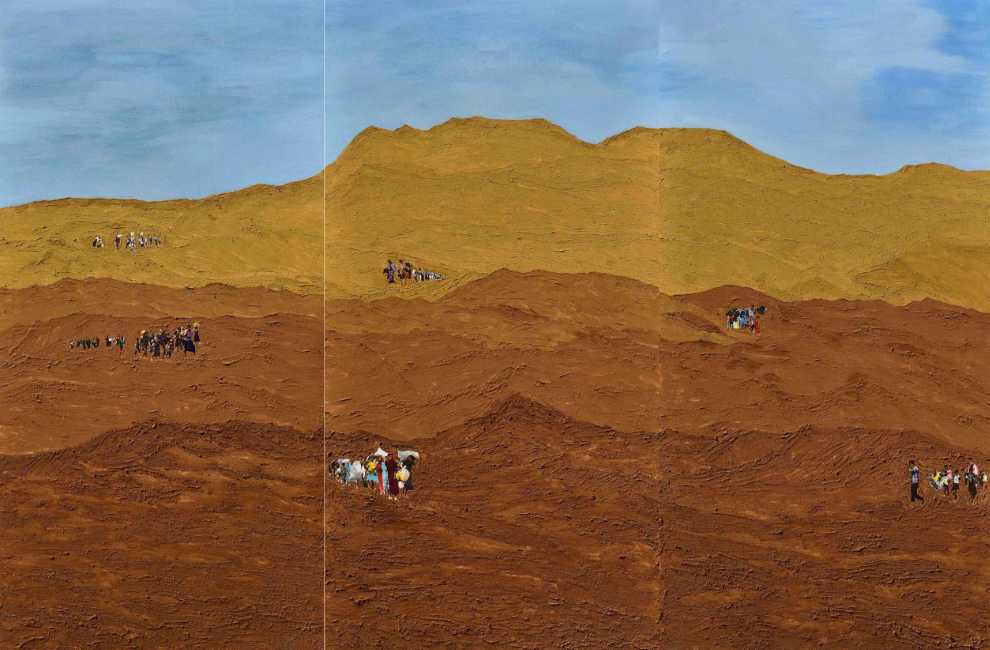

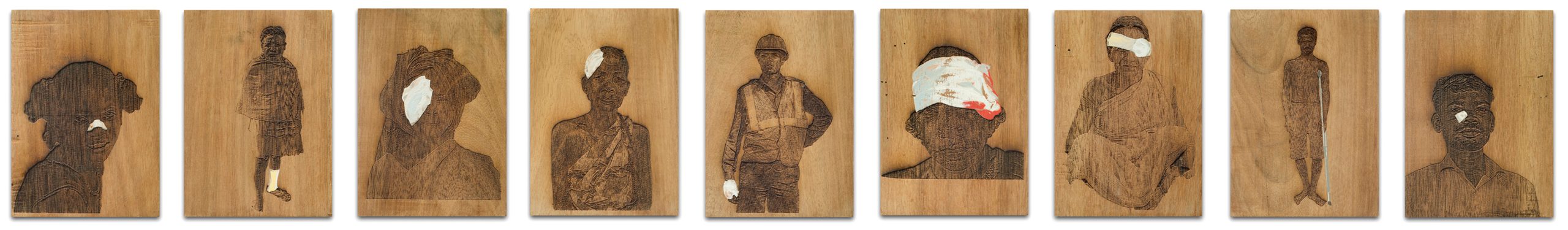

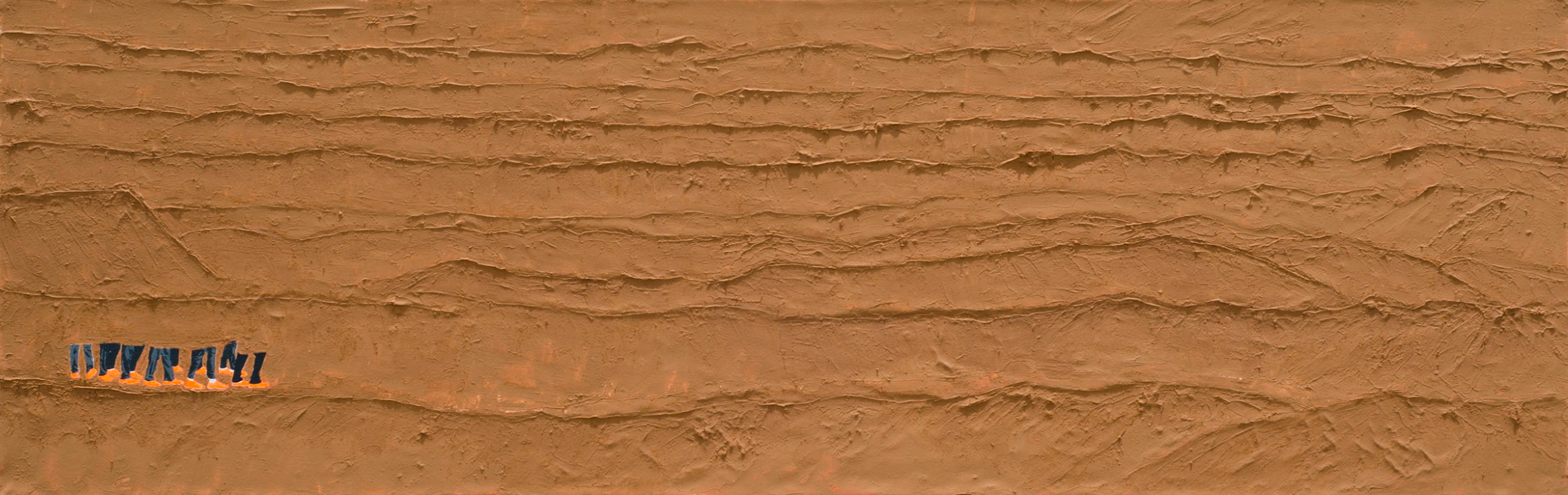

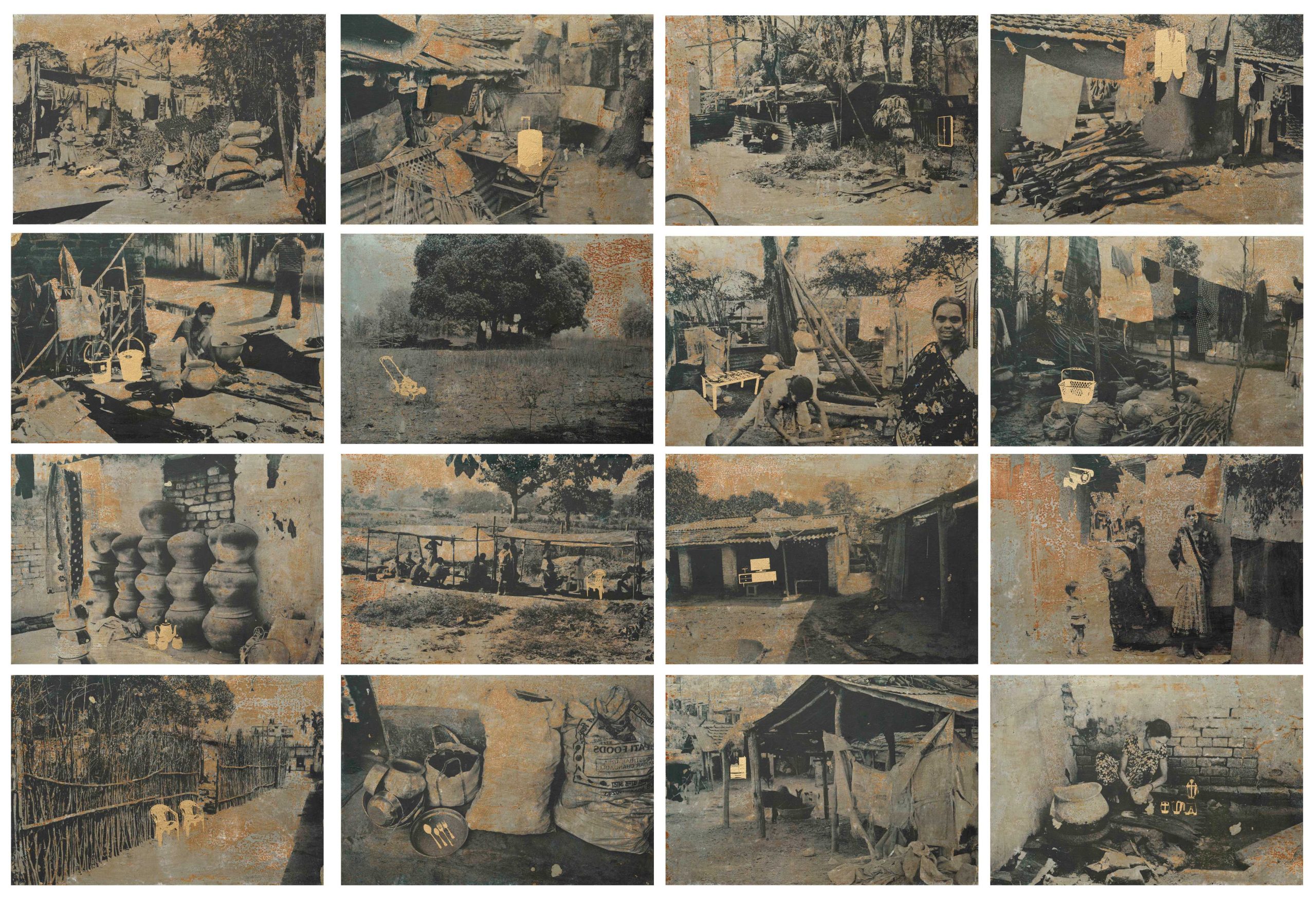

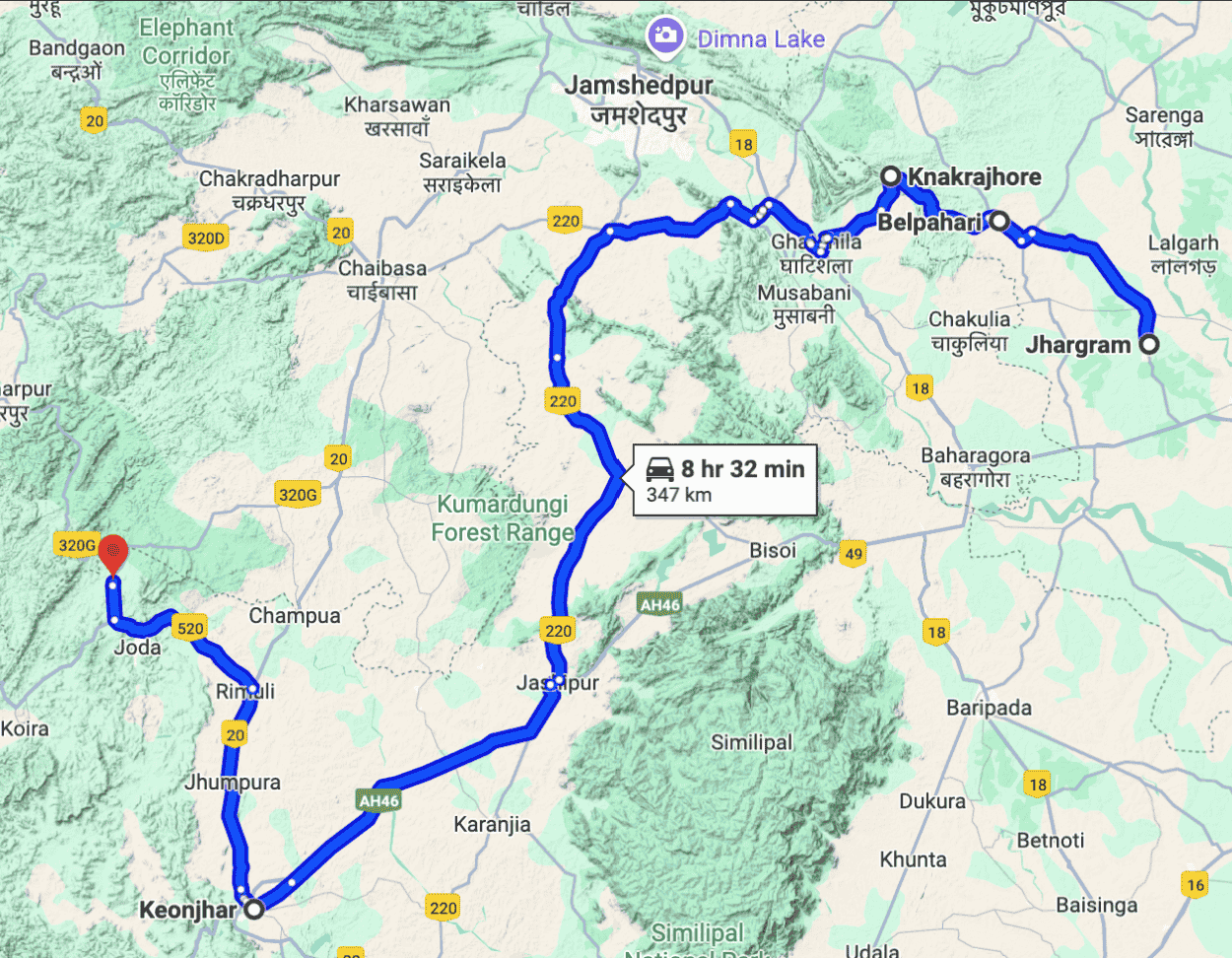

There is an anthropological pulse to Maity’s process: testimonies are methodically indexed into an archive that not only documents, but also re-envisions an epistemic framework capable of accommodating otherwise overlooked subaltern narratives. In They are Looking For a New Village (2022), made using serigraphy printing and soil applied impasto onto canvas, groups of people appear dispersed against a desolate expanse of land. The ochre-yellow laterite soil — sourced from her fieldwork in the villages of Keonjhar, Belpahari, and Jhargram — lends a political contiguity to the work, while the imagery of relocation hints at mass displacement in the area. Made in the years following the Covid-19 pandemic, it is interesting to also think about Maity’s imagination oscillating between the country’s urban metropolis and its peripheries — a condition tied as much to economic necessity as to a slow attrition of identities. The latter, perhaps, finds sharper resonance in an earlier work, When They do not Dance (2018), where she depicts only the uniform-clad legs of mine workers, suggesting a form of assimilation that both dispossesses Adivasis of their cultural distinctness, while homogenising them within an industrial workforce.

The textural depth and multiplicity of applications afforded by serigraphy make it one of Maity’s preferred techniques, which she applies across metal plates, paper, and canvas. Series of smaller-sized works like Portraits from Different Land (2019), Untitled (2021), and Introduction of a Different Way (2019), are clearer and concise, as they limn an intimate portrait of people’s daily routines. They are especially attuned to the tensions and complexities that arise with the acceptance of modernity as labour gets mechanised, and older ways of living grow obsolete. The inherent violence of being “othered”, encoded within these encounters, does not go unnoticed, and is inscribed in works such as When They Stopped Dancing (2018) and How They Looked At Us (2021). Elsewhere, in Wall of Traditions (2021) and sculptures like Dysfunctional Tools (2022), she chronicles baskets, drums, air-dried corncobs, pots, harvest straws, and agricultural tools with an attentiveness that foregrounds endangered customs and knowledge systems not as romanticised relics, but as critical counterpoints that lay bare the promises and failures of “development.”

Although trained as a print-maker, there is merit in situating Maity’s choice and treatment of metals like iron, copper, and brass both within the history of sculpture-making, and also, within the region’s indigenous craft traditions like Dokra (lost-wax casting), to understand how she frames the social ecology of minerals, alongside considering divisions between ‘high art’ and ‘craft’. In Untitled (2022), she props up brass figurines of mining equipment, and worker safety gears like helmets, vests and boots onto paintings of traditional architecture features like the chabutra and wooden chaukhat. Similarly, in her series, In a Span of 15 Years (2023), brass airbricks symbolically bridge transitions between homes made of mud to those of concrete. Through such frequent material juxtapositions, Maity is able to promptly interlink people’s labour and land — the terms and conditions to which are regularly negotiated under a neo-colonial, capitalist order.

During one of my conversations with Maity, I impulsively tried mapping the names of villages online to trace her travels from the Jhargram district in West Bengal to as far as Kendujhar in Odisha. We spoke about the everyday livelihoods of the Santhal, Munda, and Lodha tribes; about Sonajhuri, Mahua and Sal tree plantations; and from Tarfeni river Barrage, and the Damodar Valley Corporation, to annual cropping, and immigration patterns in Belpahari. She explained how hydroelectricity and iron-ore mining projects have not only displaced Adivasis from their lands, but also depleted groundwater, eroded forests, and caused recurrent floods by altering the river’s course. At the same time, protests against forced land acquisitions, non-consensual relocations, and human trafficking have rarely drawn the attention of mainstream media, while public opinion remains dismissive — often reducing Adivasi struggles to Naxalite-Maoist extremism.2 One only has to look back at the Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh violence between 2007 and 2009,3 or the starvation deaths among the Sabar tribe community in Amlasol in 2004,4 to understand the extent of bureaucratic mismanagement, state-sponsored human-rights abuse, and police brutality in the region.5

In the preface to The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India, interdisciplinary scholar Rahul Ranjan emphasises upon “writing from a place of solidarity… as a submission to learn and listen to Adivasis; to be able to speak with, not for, them; and to be able to write alongside, not on, them.”6 I believe Maity poses a similar “alongsidedness” through her practice: a way of being with and returning to a people, whose histories, landscapes, and resilience synthesise into her own modes of making and remembering.

- ‘(Un)Layering the future past of South Asia: Young artists’ voices’ curated by Salima Hashmi and Manmeet K. Walia. 11 April 2025 to 21 June 2025 at the SOAS Gallery, London. The work on display was titled Changing the Course of the River (2024).

- A 2015 study published by Bagaicha Research Team on alleged “Naxalite” undertrials in Jharkhand revealed how large numbers of Adivasis, Dalit and other backward castes were caught in false police cases. Most of those who were accused as being Maoists or ‘helpers of Maoists’ were arrested, and imprisoned based on misinformation. Other findings also included a large number of fake cases under the 17 CLA Act, UAPA, and the anti-state sections of the IPC. See Antony Puthumattathil SJ, Marianus Minj SJ, Renny Abraham SJ, Stan Swamy SJ, Xavier Soreng SJ, Sudhir Tirkey, Damodar Turi, and Jitan Marandi, Deprived of Rights Over Natural Resources, Impoverished Adivasis Get Prison: A Study of Undertrials in Jharkhand (Ranchi: Catholic Press Ranchi, 2016), https://sanhati.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Undertrials.in_.Jharkhand.pdf.

- See Santosh Rana, “Lalgarh: A People’s Uprising Subverted by the Ultra-Leftists”, Revolutionary Democracy, July-September 2009. https://revolutionarydemocracy.org/rdv15/lalgarhnew.html. Also see Sumit Sarkar and Tanika Sarkar, “Notes on a Dying People”, Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 26/27 (2009): 10–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40279767. A consolidated archive of fact-finding reports, and overviews on Lalgarh, Nandigram and Singur is also available on the Sanhati website. https://sanhati.com/excerpted/1083/

- Olivier Rubin, “The Politics of Starvation Deaths in West Bengal: Evidence from the Village of Amlashol,” Journal of South Asian Development 6, no. 1 (2011): 43–65, https://doi.org/10.1177/097317411100600103

- For a detailed overview, see a collection of short-essays and texts in Fr. Stan Swamy, “Adivasi Resistance to Mining and Displacement: Reflections from Jharkhand” (updated April 20 2015), Sanhati, March 10 2015, https://sanhati.com/excerpted/12884/

- Rahul Ranjan, The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), xx

Bio

Satyam Yadav (he/him) is an independent arts researcher and curator based out of New Delhi. He is interested in questions of the political economy, contemporary arts, and visual cultures of health, labour and sexuality in relation to wider bio-political histories of South Asia. He has worked as a writer and researcher with several art institutions and universities in India, alongside working with artists. Recent curatorial projects include akâmi- at the Camden Art Centre, London, 2025; Lateral B(l)inds at the India Art Fair YCP, New Delhi, 2024; Natura Urbana, at the Academy of Fine Arts and Literature with Ether Project, New Delhi, 2023; Ways of Our Lives, Somaiya Vidyavihar University, Mumbai 2023, and Embodied Encounters, at the Ram Chhatpur Shilp Nyas with Ether Project, Varanasi, 2022. He was the 2024-25 curatorial fellow at New Curators, London, and the recipient of IMMERSE curatorial residency, Mumbai, 2022-23. He is also a student on partial scholarship in Art and Curatorial Practice at the New Centre for Research and Practice. Satyam holds a MA in Gender Studies from Ambedkar University Delhi, and a BA (Hons.) in History from Ramjas College, University of Delhi. He currently works with the Prameya Art Foundation (PRAF), New Delhi.

The Photo Develops You: four photographic engagements with the environment

AUTHOR

Aparna Chivukula

Many years ago, walking in a forest in Honnemaradu, with the light fading from the path, a friend told me to pause before scrambling for my torchlight. Slowly, we lost sight of our feet. The slippery edges of the trail retreated into complete darkness. The outlines of the trees, the rocks, and our bodies disappeared altogether.

And then — shapes began forming. A faint scribble of thorns near my ankles. Silk-seeds from the honne trees, strewn like coins, materialised before us. It was an image of the forest, developing itself in the dark.

Some photographers carry a memory like this too — a moment when a route they walk every day, camera in hand, finally reveals itself to them. It is a moment they wait for, tweak their process and materials for, walk the same path again and again for. It is not so romantic as a communion, nor as aggressive as a capture. While practices of making photographs of or about the environment are popularly described under the broad banners of ‘ecological’ or ‘eco-political’ art, practitioners’ intentions and experiences are also often driven by the desire to find and maintain a more meaningful, personal relationship with their surroundings.

In conceptual artist Atul Bhalla’s photography and photo-performance work, the artist regularly implicates himself, by making his own body visible — locating crisis in both human experience and the natural environment, the two conditions reflective of one another. In the photo-series Looking for Dvaipayana1 (2014), he performs in locations around his hometown, Delhi, that have been named after water bodies which are no longer visible or remain only in the memories of older generations. In one photograph, taken on Panchkuina Road — a street named after five wells — the artist sits in the middle of the road, head hung low in defeat or submission, as though the sight of this place, once abundant with water but now paved over, has collapsed him.

Bhalla steps away from didactic strategies of displaying the devastating impact of human activity upon the natural world. Instead, he presents a more embodied narrative, underscored by personal loss and intergenerational memory. The environment, the public, and the personal are deeply enmeshed and cross-reflective in these photographs, encouraging readings of Delhi’s water crises that are also emotional, mythological, and biographical.

Photographer Tenzing Dakpa takes a different approach to building connection with his surroundings — rooted in the practice of walking around his locality and making observations with the camera. Dakpa negotiates a belongingness to his present home, Goa, through prolonged attention to its natural and built environments. His series God’s Gift, photographed over eight years, documents this habitat and the process of making a home through the care, upkeep, transitions, and destruction found in his vicinity.

At times, these images reveal dissonance or anomaly, where a landscape reaches in one direction and its inhabitants in another, in an effort to control or change their environment. This calls to mind philosopher Isabelle Stengers’ idea that conflicting interests are a general feature of any ecology. Stengers’ reflection that “the creation of rapport between divergent interests as they diverge” results in “novelty, not harmony”2 resonates with much of Goa’s slowly transforming landscape in God’s Gift. In Fresh Paint, Olaulim, 2019, for example, we behold this novelty in the unusual form of the red tree trunk — someone’s way of using up extra paint. Dakpa’s photographs make visible the creation of this evolving rapport between surroundings and inhabitants; the conflicts, resolutions, and humour born out of these interactions.

For Dakpa, the vagaries of an environment and its inhabitants become legible through the practice of photographing the same place over a long period of time. There is no pre-formulated ‘subject’ which he scouts for, nor any performance involved to stage the image. Instead, he calls for a more generous approach — one that gives space and attention to the other presences involved in making his photographs: the environment, its existing structures and objects, their abstractions, suggestions, sensations, and the artist’s instinctual responses to them. In this way, Dakpa releases the photograph from the stronghold of a pre-formulated idea, or an ideological vision, and locates his work in a more uncertain, fluid playing field.

Multidisciplinary artist Anuja Dasgupta’s work with anthotypes pushes further the question of how an environment can contribute to the images that depict it. Her anthotypes are camera-less photographs, made by coating cotton paper with light-sensitive emulsions derived from seasonal plants native to her surroundings in Ladakh. Left by river banks to develop, these prints carry the marks, movements, and textures of the insects, cattle, plants, and river drift that come into contact with the paper. The resulting anthotypes are compositions shaped by anonymous elements and creatures of the region.

A starting point for Dasgupta’s practice of photographing Ladakh was her encounter with the book Ladák: Physical, Statistical, and Historical; with Notices of the Surrounding Countries (1854) by Alexander Cunningham, the first director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India. The book claims in its preface to be ‘a full and accurate account’ of Ladakh. Troubled by Cunningham’s representation of the region as unable to support life, Dasgupta produced Four Full and Accurate Accounts of Ladák (2018) — a series of books with paper made from the area’s soil, sand, and juniper, containing photographs, writings, and drawings by students from Lamdon Model School in Leh, alongside her own travelogue, juxtaposed with excerpts from Cunningham’s text.

Her inquiry into how life sustains in the harsh climate conditions of Ladakh continues through her anthotypes — photographs the environment itself works upon. The plant-based emulsions depend on seasonal foraging, creatures leave traces upon the emulsion-coated paper, and the prints themselves are prone to fading over time with exposure to light.

Dasgupta argues that the anthotype (from the Greek anthos meaning ‘flower’, and typos meaning ‘imprint’) is generally labelled as an ‘alternative’ photographic process because the dominant ideal for modern photography is precision, control, speed, and capture. The anthotype process instead invites an engagement with the more alchemical, volatile characteristics of one’s surroundings — moving away from a realistic or calculated capture of nature. As photographers’ desires shift, they seek out fresh modalities and search for other histories of image-making with nature. Dasgupta cites as an influence the 19th-century scientist Mary Somerville, who experimented with vegetable juices to develop different catalysts, contrast-makers, and enhancers — recording how juice from the same plant could produce different results depending on how it is extracted or what kind of light it is exposed to. In this way, these shifts in practices encourage the processes that are deemed as solely ‘alternative’ to be recast as historical photographic processes.

Santiniketan-based visual artist Surajit Mudi takes on another set of historical questions: what has been the role of the photographer in shaping a public’s understanding of their environment? How has the reputation of the photo-object been transformed by its focused circulation in art galleries, magazines, and the internet? Mudi explores these issues by travelling to different locations with his mobile studio: a customised version of an Afghan box camera — a camera and a darkroom in one — mounted onto a cycle, which also serves as a tripod.

In public gathering sites, such as marketplaces, Mudi invites people to witness and participate in the process of making a photograph, and discuss their responses and experiences. He maps these stories and conversations in the form of a visual travelogue, rich with anecdotes, mythology, and anxieties around the photograph — such as ghosts captured on negatives, the belief that photos turn their subjects younger, or trap their souls, memories of family albums, and suspicions many have towards the usage and circulation of photos taken of them.

The mobile studio opens new routes for both making and circulating photographs. It also complicates the reputation of the photograph as a realistic, unmediated representation of the environment — by giving attention to the myths around it, and publicising the variability, choices, and uncertainties involved in its making. By asking inhabitants to document their own surroundings through slow, unfamiliar processes, and think through this act together, Mudi fosters a slow, public re-looking at one’s environment, imagining new purposes and modes of consumption for the photograph.

His exploration of disrupting subject-object positionalities in photography extends to public workshops where participants make pinhole cameras with objects collected from their surroundings, such as discarded cardboard boxes, matkas, coconut shells, or soft drink cans. The object-turned-camera is then taken to where it was found and is used to take a photograph — revealing how the object ‘sees’ its own landscape. In one such workshop, a clay pot photographed the building near which it was found. The result was a photo-fragment with hazy edges that noticed a branch reaching towards a window and a tear in a neighbouring sheet of tarpaulin. As Ursula Le Guin suggests, the act of subjectifying need not necessarily “co-opt, colonise, exploit. Rather it may involve a great reach outward of the mind and imagination.”3

In each of these photo-practices, we find the artist walking outdoors, deciphering their environment’s vernacular, and intentionally fine-tuning their conceptual or material processes — out of a desire to be able to listen, when they are finally spoken to.

Footnotes

1 Dvaipayana meaning ‘that which is surrounded by water’, taken from the story of the birth of Veda Vyasa on an island in the Yamuna river.

2 Stengers, Isabelle. “Comparison as a Matter of Concern” Common Knowledge, vol. 17 no. 1, 2011, p. 48-63.

3 Ursula Le Guin, “Deep in Admiration”, in Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Heather Anne Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt, eds. Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene. Minnesota: Minnesota University Press 2017, M15-M22.

Indian Art in Service of Ecological Activism

AUTHOR

Mustafa Khanbhai

Year on year, the climate crisis grows more pressing, with news headlines about population displacement, frequent natural disasters and species extinction now fixtures of everyday life. Commentators have noted that while scientists, activists and indigenous communities have led movements against the continued deterioration of natural habitats and the commons, political will to address this remains tepid.

The climate emergency demands frameworks that exceed disciplinary silos, and contemporary art’s increasing engagement with ecology reflects this epistemic shift. Recent surveys of climate-oriented art practices have outlined how artists have responded to the planetary scale of the crisis with both localised inquiry and global critique. In contrast to early environmental art, which often romanticised nature or positioned it as a passive site of intervention, recent ecological art sees nature as a politicised and contested terrain. A growing number of artists are dissolving the boundaries between environmentalist and artistic movements, situating their practices within the infrastructure of activism itself. This essay will review recent experiments by artists and organisations to embed art in direct activism, invite the wider public to bear witness to climate catastrophe, and engage in frank discourse on the responsibilities of the artist in an age of collapse. The aim is to explore how art operates not only as a medium of ecological expression, but as a site of material engagement, networked resistance, and the co-creation of alternative environmental futures.

Artists not only comment on social realities but are themselves entangled in the material conditions of global circulation, funding networks, and civic fragmentation. Scholars like Karin Zitzewitz have noted that art institutions — whether commercial or non-profit — often make it a point to carefully gerrymander any practical activism out of the projects they support, framing them instead as matters of logistics, mobility and legibility for diverse audiences. The goal of the NGO is often to make politically engaged, context-specific art easily digestible and globally presentable, rather than deploying it to actively solve the issues it raises. As a result of this not-so-porous border between the black box (or white cube) of the art world, and the noisy, chaotic ‘real world’, meaningful projects often reach only those audiences already supported by the same institutions. Over time, the vocabulary of artistic interventions in the public sphere has become increasingly oriented around institutional appeal rather than relevance to affected communities. Consequently, artists and curators may feel ill-equipped to engage with their subject directly, instead seeking institutional shelter from the consequences of taking anti-authoritarian or anti-corporate stances.

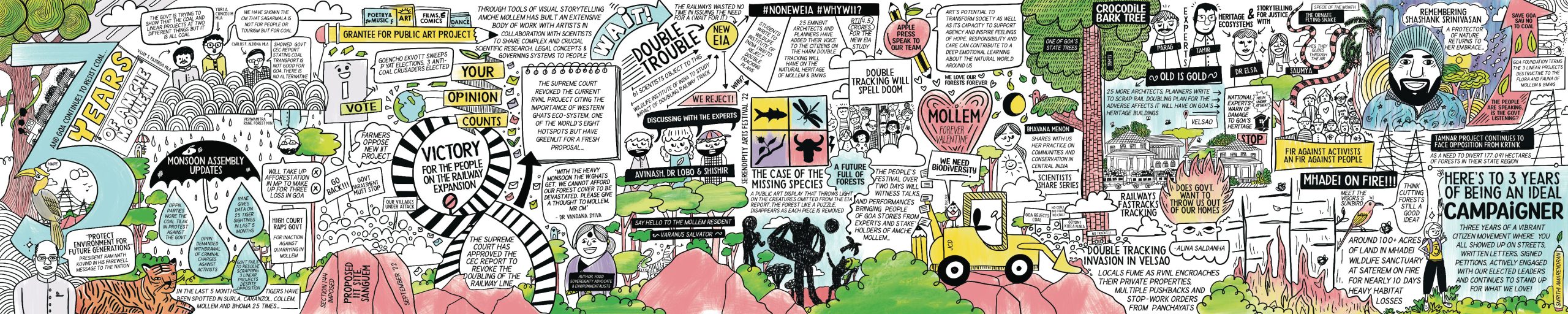

New forms of activism in the digital age have created avenues through which artists can influence public opinion.The Amche Mollem campaign in Goa offers a powerful example of art serving a pressing cause, rather than existing as a sharpened but ineffectually cloistered hobby. Amche Mollem began in June 2020 in response to a government plan to lay double railway tracks and transmission cables in South Goa primarily to move coal through the region. This would have required cutting down large swathes of forest in the Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park, endangering several protected species including some unique to the region. The campaign succeeded the following year, when the plans for the rail were scrapped and the transmission lines were relocated. However, it has had to repeatedly mobilise against similar threats to natural habitats in Goa and other fragile ecologies across India.

Over the past five years, Amche Mollem has evolved into a kind of para-institution, where legal and scientific expertise converge onto political pressure points, and young artists across Goa, with their otherwise individual practices, have been invited into the movement. Over the past five years, both professional and amateur artists have created and shared work to revive interspecies empathy and kinship among a public that has grown steadily disconnected from the natural world, and has become absorbed into the development-first narrative driving India’s economic and industrial policies. Artists such as Svabhu Kohli, Deepti Megh and Nishant Saldanha have contributed illustrations for social media campaigns and installations at art festivals, depicting endangered species threatened by development projects, explaining complex food webs and migration patterns in Mollem and beyond, highlighting human-animal relationships, and stressing the importance of preserving these natural spaces. While legal support for the movement has come from the NGO Goa Foundation, artistic interventions in the form of workshops and public installations have been facilitated by organisations like the Serendipity Arts Foundation, the Museum of Christian Art and Arthshila Goa, reaching a wide cross-section of residents. By moving through several nodes and forms of engagement, the art becomes completely enmeshed with the activism: functional, organic, and instrumental in translating legal and scientific arguments into accessible visual language.

A less direct yet effective form of ecological art has emerged in recent years through public-facing invitations to witness the climate catastrophe. One valuable example is the 2008 festival 48°C Public.Art.Ecology in Delhi. Artists including Ravi Agarwal, Navjot Altaf, Atul Bhalla, CAMP, Sheba Chhachhi and Krishnaraj Chonat presented interactive, site-specific installations, supported primarily by the Urban Research Group, and to a lesser extent by the Goethe Institut and the Delhi Development Authority. While some projects suffered from shallow engagement or didactic spectacle, 48°C was a landmark undertaking that brought ecological art out of galleries and into the public sphere where artists had to cater to an audience that was almost entirely unconnected to the art world and art discourse. Installations were placed strategically near busy interchange stations along the Delhi Metro’s Yellow Line to attract the city’s general public. The festival’s focus on scale, legibility, and the voluntary engagement of the viewer allowed the works to reach beyond art audiences and create moments of provocation and reflection in urban spaces. The shock value of some installations and the interactive nature of others sparked enough meaningful engagement that 48°C is now seen as an overall positive step in the history of ecological art in India.

While a healthy presence in the public sphere remains crucial for maintaining the relevance of ecological art, it is equally important for artists and the institutions which support them to ask: why do artists matter in a climate crisis? The 2017 performance Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness, organised by KHOJ International Artists’ Association and Zuleikha Chaudhari, addressed this question directly. Framed as a mock hearing on the Indian Rivers Interlinking Project, it featured artists as witnesses being examined by lawyer Anand Grover and defended by Arpitha Upendra. The performance became a Socratic dialogue on the role of the artist as an agent of change. For this reason, Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness can be read less as a performance and more as a critical text. It opened up a complex discussion on the role of artists in legal and environmental issues, giving equal space to knee-jerk arguments like those found in Instagram comment sections, and to nuanced commentary on the social responsibilities of privileged artists and the value of empathy over economic anxiety.

What emerges across these examples is a clear call for art to move beyond functioning merely as a site of representation and become an infrastructure of relation. The most potent ecological artworks are those that generate publics, assemble knowledge, and foster coalitions across differences. They do not treat nature as a sublime and distant aesthetic object, but situate it as a terrain of struggle shaped by law, extraction, dispossession and resistance. They help rethink planetary coexistence not through universalising narratives, but through a patchwork of situated, entangled and politically conscious practices.

Bijolia, Disha. 2022. “Inside An Artist-Led Campaign That Saved Goa’s Biodiversity.” Homegrown, October 26. https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-creators/inside-an-artist-led-campaign-that-saved-goasbiodiversity.

Das, Arti. 2023. “A Future for Forests: Amche Mollem.” ASAP, April 5. https://asapconnect.in/post/552/singlestories/a-future-for-forests.

Demos, T.J. 2013. “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology.” Third Text, 27: 151–61,doi: 10.1080/09528822.2013.753187.

Fowkes, Maja and Reuben. 2022. Art and Climate Change, Thames & Hudson.

Roy, Sreejata. 2024. “Socially Engaged and Public Art in India: A Chronology from 1990 to the Present (Part 1).” Field, 1 (28). https://field-journal.com/issue-28/socially-engaged-and-public-art-in-india-a-chronology-from-1990-to-the-present-part-1/.

Zitzewitz, Karin. 2022. Infrastructure and Form: The Global Networks of Indian Contemporary Art, University of California Press.

LOGIN to see more

To see all the content we have to offer, login below

OR

Don't have an account?

REGISTER FOR FREE

REGISTER FOR FREE

Registration is completely free, stay connected to Serendipity Arts