The Phantom of Vulgarity around the Voluptuous Body

A complete break from defying conventional understanding of body and gender appears to be nearly unachievable. Often efforts to do so succumb to the brackets of dominant definitions, albeit unintentionally. In the context of Indian art history, the term fat is remotely invoked. The wave of presumption to measure the moral quotient in accordance with the “voluptuous” body was ushered in with the onset of the British Empire[i]. However, it is beyond the scope of this text to historically contextualise and trace the visual representation of the fat body of women across the genres in India. The ensuing discussion is an attempt to underscore the exhilarated interest of the art practitioners of the late nineteenth–twentieth century, especially in popular culture, to perpetuate the representation of the uncontained body as a site of mockery that further cemented fat-phobia, clinically termed as lipophobia.

A lost opportunity was the 2018 horror-comedy movie Stree. The movie received critical appreciation for its ironical undertones as it showcased men experiencing everyday challenges that are otherwise faced by women. Paranoia to take a late-night stroll, the need to follow appropriate dress code to avoid the male gaze, and the fear of being labelled a social pariah if the partner was chosen by the person and not parents are a few of the anxieties women are made to experience in the patriarchal societal structure. Within the satirical framework, the men of the region Chanderi are forced to step into women’s shoes as an act to ward off the invisible yet possible threats of the looming danger from the spirit Stree. Against the contingent of men, the movie about the subversion of the patriarchal discourse on women and social decorum has three women who make their presence on the screen, besides Stree (the apparition): Stree—led by Flora Saini; the lead protagonist—Shraddha Kapoor who is a protector-cum-witch; the one-time performer—Nora Fatehi; and the sex worker—Atmaja Pandey, who appears twice.

The movie, which wants to extend the feminist point of view, falters by representing its female characters through stereotypical bodily conventions. Instead of disturbing the social construct, the movie perpetuates the parallel between the body of the woman and her character. The discerning eye cannot ignore the synonymy of wasp waist with the sensuous charm and polite speech of Kapoor, and the fat body of Pandey with raw expressions and crass language. Even though the movie nudges its male characters to draw a new line of thought on feminism, it confines the female characters to a stereotypical formula. The non-adherence to bodily standards of a decent society, the fat body attracts the stare from the viewers of the comfort zone.

The movie, in an effort, to make the men get a taste of their own medicine remains woefully short to provoke us to see the world under a new lens stripped of bodily conventions. The consumerist popular culture opens an opportunity to navigate the contradictory approaches to derivative prejudices. Rather than having monolithic views feeding into confirmation bias, the multiple perspectives invigorate critical discussion. Under the satirical tones, the oblique treatment of the excess flesh creates a lacuna to be filled by another celluloid, free of the burden to make representation palatable to the larger audience.

Before Raja Ravi Varma’s representation of female divinities on oleographs, the goddesses as a manifestation of purity were sacred enough to be guarded against the public eye. Soon the mass production of the lithographs and oleographs in the nineteenth century heralded the way for mass art production, loosely termed calendar art. It promoted a standardised representation of woman-the semi-clad curvaceous body holding an odd posture.

Image Credits: Stolen Interview, Raja Ravi Varma, Courtesy: Creative Commons

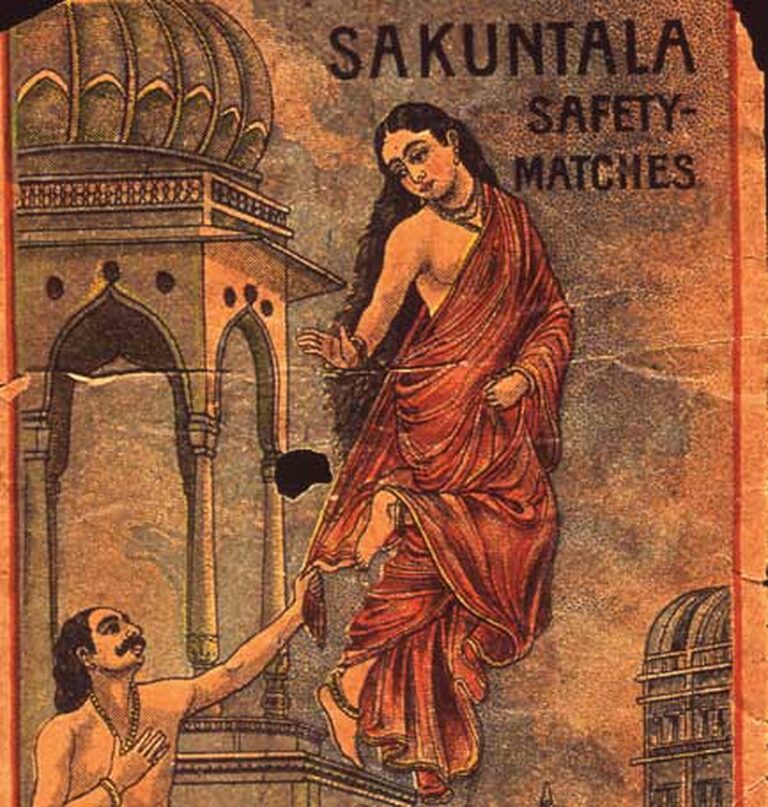

As the goddess was moved from within the walls of sanctity into the public sphere or bazaar, it turned into a profane woman and no longer a subject worthy of emulation. Exemplifying the same is the visual representation of Sakuntala and Dushyanta on a matchbox.

The Calcutta-based Parimal Ray collects an array of the paraphernalia of the bygone era’s popular visual arts—available at fairs, junkyards, and streets. In one of his collections, a matchbox carries the image of Shakuntala in a red-saree and the gesture of her hand pointed towards Dushyanta suggests refusal. If the traces of Varma’s stylistic approach to the visuals are not hard to ignore, it reinforces the “Swadeshi” flavour. Kajri Jain in her book Gods in the Bazaar explains the major critiques of the calendar art that has stemmed from the lithograph industry: “On aesthetic grounds, [this genre of printed image] has been condemned its derivativeness, repetition, vulgar sentimentality, garishness, and crass simplicity of appeal…” Conforming to the zeitgeist of the times, the image of Shakuntala, made popular by the lithographic prints, borders on the norms of domesticated modesty and unabashed display of desires.

Image credit: Sakuntala, Matchbox Label, Early 20th Century, Courtesy: Parimal Ray, From the archive of CSSSC

The disjunction between the art period based on the temporal axis of tradition and modernity; access to the high or low art set the ground of aesthetic tastes: refined and vulgar.

The Kalighat paintings of the same time turned women into a spectacle for the commoners. The rose in the miniature art of medieval India served the purpose of both euphemism for and symbolism of representing the emotive sexual desires. Years later, the red flower in the hands of the so-called crass women in Kalighat paintings was reduced to a degenerative symbol of sexual advances: the domestically tamed flower is not to be turned into an immoral subject of public viewing[ii]. When the private acts of ease, leisure, and refinement are transmuted into the domain of public, it falls from the state of grace to debasement. Here, the metaleptic rose once again confirms the inherited frames of looking and perceiving the hackneyed representations of the epithet vulgar.

Image credits: Maid Bringing a Hookah to a Lady, Courtesy: Creative Commons

The critical discussion around fat female bodies as morally insufficient has remotely gained momentum in the western discourse of visual arts. It is predominantly an area of research interest for disciplines including media, cultural, and sociology[iii]. Despite academic scholarship, across the disciplines, on the body, especially in India, intellectual curiosity could not detach an array of adjectives from the body. More often than not, dissuaded as an object of ridicule, the dominant cultural discourse constructs a spectacle on the body that could not fit within the parenthetical appropriate measurements. To liberate the voluptuous body from the phantoms of the vulgarity, its visual representation devoid of clichés on the popular platforms is the first step forward towards a positive viewpoint. It is easier said than done. The necessity to reconfigure female fat bodies opens critical dialogue on the social construction of parallels between crassness and the uncontainable body.

It could be argued that visuals do not predominantly account for the fear of fat, the visceral responses to the desirability of wasp waist, which are embedded in the long social and medical history. Furthermore, the visuals are even dubbed as apolitical having little significance on the minds of the audience. Having said that, it cannot be denied that weaving in and out of the reversal chronology[iv] is the notion that the popular culture with these obsolete portrayals triggers an implicit bias. The importance attached to ‘what is framed’ and ‘why it is framed’ prompts to scrutinise the internalised behaviour of the immediate consumer of the popular culture—the audience. The regular engagement with the floating abundance of the visuals set the yardstick to measure the standards of body shapes and asinine behaviour. Subsequently, for the interpellated subject, the task to undo the epistemic structures is complicated when the surge of the visuals acts as a reification of truth in mainstream narratives. Hard to be removed from the site of public spectacle, the representation of the body is not exclusive to personal and political framework of assessment.

[i] Nead, Lynda. Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

[ii] Archer, Mildred. Indian Popular Painting In The India Office Library (London), New Delhi: UBS Officer. 1977.

[iii] Snider, Stefanie, “Fatness and Visual Culture: A Brief Look at Some Contemporary Projects.”, Fat Studies 1, no. 1, (2012): 13-31.

[iv] Nietzsche, Friedrich, Werke, Translated by Schlechta. München : C. Hanser Verl., 1966.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dilpreet Bhullar is a writer-researcher based in New Delhi, India. She has an MPhil from the University of Delhi in Comparative Literature. She is co-editor of the books Third Eye: Photography and Ways of Seeing and Voices and Images. Her essays on visual sociology, identity politics and refugee studies have been published in books, journals and magazines including Designing (Post) Colonial Knowledge: Imagining South Asia (Routledge), The Third Text (Routledge), South Asian Popular Culture (Routledge), Indian Journal of Human Development (Sage Publications), Himal Southasian, and the digital archive www.criticalcollective.in, to name a few. She is associate editor of the theme-based journal on visual arts, published by India Habitat Centre, and feature writer at

STIRworld.com