Beyond Flesh: An Interplay between the Internal and External Narratives of the Body in Performance Art

AUTHOR

Tejaswini Loundo

“We are the material, our bodies and minds the medium of our exploration. The research is experiential as is the material.”[1]

I – First Words

The human body is a landscape made of our various experiences, like a living, breathing, expressing canvas. The physical form (deha) is home to the spiritual form (ātman). Indian philosophy views the body as a miniature version of the universe itself: a microcosm where our physical and metaphysical existences profoundly entwine. The body is the medium through which we experience the world and the instrument through which we perceive, think, act and reflect. Through its physical processes and expressions that shape one’s external narratives, the body conveys the multitude of one’s inner processes – the emotions, thoughts, and experiences that shape one’s internal narratives.

Let’s take for instance, the reader. At this very moment, the reader is focused on reading the sentences. The eyes follow from word to sentence, sentence to paragraph; maybe every now and then his/her face expresses doubt, surprise or curiosity; or the fingers may be fidgeting as a natural response to his/her state of concentration. Alongside reading the sentences, the reader is concomitantly aware of what the sentences connote, as he/she engages in the cognitive process of ‘making sense’, using their opinions and experiences as raw material.

J. H. Gill states: “Human existence is characterized by a unique amalgamation of conceptual, or symbolic, activity and physical embodiment. We are at once both mind and body, even though in some contexts we may seem to participate more fully in one or the other. We attend either from our bodies through our minds to the world, or from bodies directly to the world”.[2]

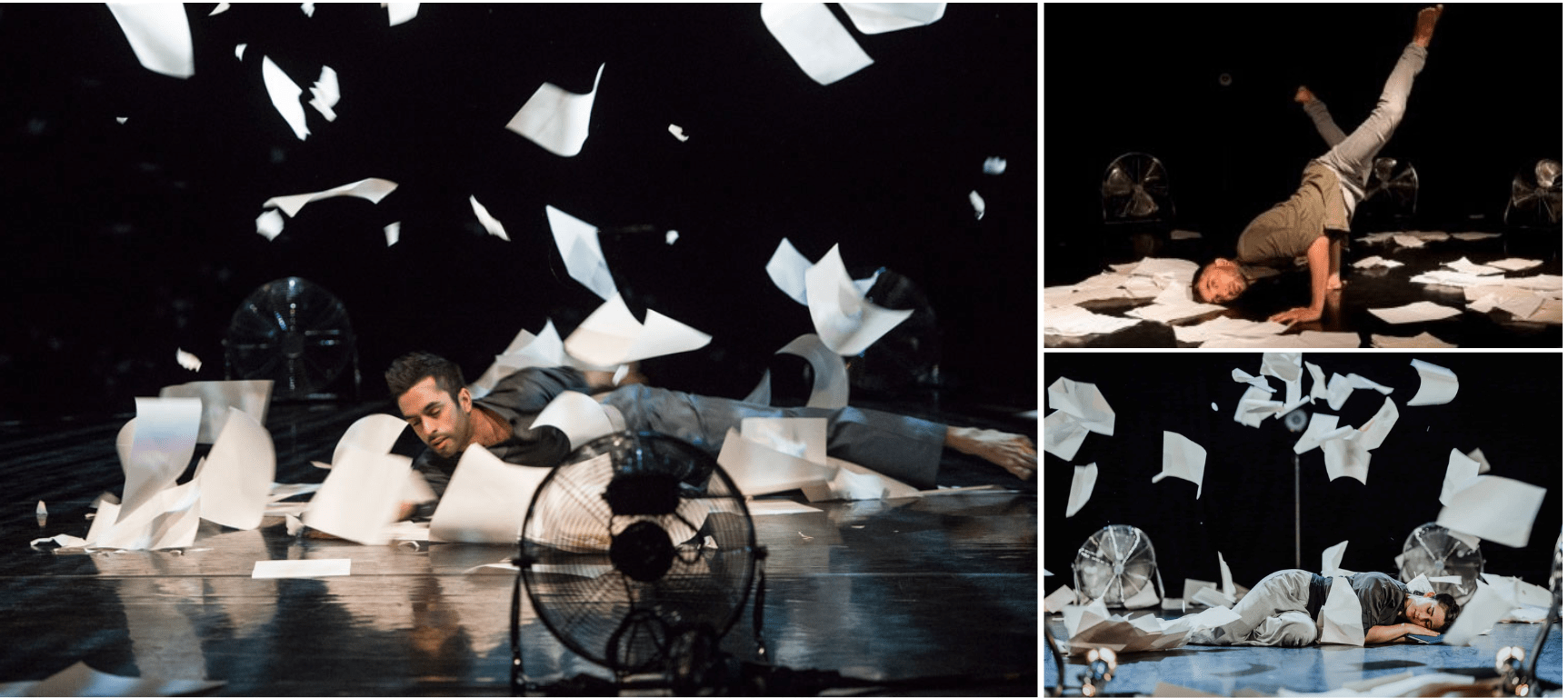

This interplay between the individual’s internal and external becomes especially relevant and evident in the realm of performance art, and especially in movement.[3] Accordingly, the body is both the medium and the site for the interplay between various narratives.

II – The Body’s External Narratives

The body does not merely house various narratives. At the most fundamental level, the physical, visible form of the body tells stories holding traces of our ancestral, personal, and social constructions. The ancestral constructions (sanskāras) are those that have been inherently passed down through generations, such as our physical features, skin colour, and mannerisms. The personal constructs make up an individual’s convictions and lived experiences, expressed through body language – the postures, gestures, gaze, makeup, clothing, adornments, and so on. The body also reflects the social-political constructs that define our cultural landscapes through spoken language, dress codes, education, etc. In essence, the body serves as a living museum that bears the traces of all that we have lived, all that we have inherited, and all that we belong to. Consequently, such constructs suggest narratives that are inseparable from any body, and moreover from a body that performs in art. Here, such physical narratives are methodically studied and executed as techniques that put in place a process of training the body so as to enable it to express appropriately and artistically.

According to the Indian aesthetic tradition of the Nātyasāstra, we may understand the external narratives of the physical body (deha) in terms of the following key elements: (i) āngika abhinaya (physical expression); (ii) vācika abhinaya (verbal expression); (iii) āhārya abhinaya (visual presentation).[4]

III – One’s Internal Narratives

Beyond the physical, the artist’s body is also rich in its internal narratives – emotions, beliefs, experiences, feelings, and values that lie at the core of one’s being. These internal narratives are inherently dynamic and ever-changing, mirroring life itself. Consequently, these deeply personal narratives are intrinsic to any work of art, as art and the artists are inextricably intertwined. And yet, while performing their art, the performer goes much beyond the confines of their own narratives, portraying characters with experiences that may differ from their reality. If so, how can an artist interpret the Other?

The Nātyashāstra postulates that human emotions (bhāva) are fundamentally universal, i.e., they belong to all people irrespective of their culture and/or faith. These bhāva or emotional states, such as love, anger, fear, compassion, and wonder, are considered to be the building blocks of human experience. As such, for a performing artist it is key to methodically study the sātvik abhinaya, i.e., the practice of embodying the essential universality of emotional states. In fact, a deeper understanding of the universality of human emotions enables the artist to delve into the depths of their ātman (soul) and realize within the depths of his/her own personal experiences, the connecting dots and links that bind him/her to all other beings. This interplay of their various internal narratives is indeed the truth of the artist.[5] By going beyond the ‘self’ and fully interpreting the character, the performance blurs the distinction between the artist and the art. Thus, “the dancer and the dance are inseparable, but neither is simply a function of the other; nor are they the same”.

IV – The Body, the Narratives, and the Audience

It’s a fact that the essence of performance art lies in the artist’s ability to transcend the boundaries of the ‘self’. For that to happen, a vital factor is the audience. Art remains incomplete as long as it does not engage the audience as an intrinsic dimension of itself. Let’s imagine a drop of water falling down into a quiet still pool. As it collides with the surface, the drop not only fully merges into the pool, but also creates a ripple that spreads out wide. This is the relation between bhāva and rasa. Bhāva, the performer’s emotional states, is the drop of water; and rasa, the shared emotional consciousness reflected in the audience, is the ripple. This agrees in toto with the etymological meaning of the Sanskrit word rasa as “juice,” “taste,” or “essence”. Accordingly, the art and aesthetic traditions rooted in the Nāṭyaśāstra study the emotional states evoked in the audience, through the consumption of art, as the rasa theory.

This collective consciousness, which gains transparency as we move from bhāva to rasa, is precisely what lends performance art its authenticity. The body is a universal language we all innately understand. Unlike the ambiguity of words, the body’s physiological expression allows it to be read, first and foremost, intuitively and viscerally, before any consequential cerebral interpretation. This is what yields its honesty. The inherent truthfulness of the body in performance empowers the artist to engage the audience, by means of their own experiences and emotions. This is further heightened by the ephemeral, fleeting nature of performance art, where each moment is a unique, unrepeatable manifestation of the artist’s physical presence. “It is, as Merce Cunningham puts it, “the art of the present tense”” (Peter Arnold, 2000).

V – Concluding Words

This capacity of performance art to resonate with the fundamental truths of the human condition, is what lends it its power and relevance.[6] These fundamental truths in a broader context, beyond the individual, are essentially reflective of social and political realities. As such, in every case, the personal is immediately social-political, and vice-versa. The body becomes the privileged site where broader issues of power, identity, politics, and human experience are explored and shared with the audience. Furthermore, placing performing bodies outside conventional artistic frameworks, such as those of non-traditional spaces (site-specific performances), challenges the dominant narratives that control those spaces. This allows questioning and alternative perspectives to emerge and expand one’s perception of space itself.

In other words, performance art harnesses the transformative power of the body which challenges and deepens our collective understanding of the world around us. Body – a repository of memories, a voice for resistance, a medium of transformation, a mirror for society – evolves dynamically prompting the world to equally evolve.

References

Arnold, P. J. 2000. “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance. Journal of Aesthetic Education”. p 87–95. <https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657> Accessed on 23/07/2024

Bharata Muni. Nāṭyaśāstra. 2014. English Translation from Sanskrit by Adya Rangacharya. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Chadha, Monima. 2022. “Personhood in Classical Indian Philosophy”. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/personhood-india/>. Accessed on 23/07/2024

Cohen, Bonnie Bainbridge. 2020. “An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering®”. <An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering® – Body-Mind Centering® (bodymindcentering.com)>. Accessed on 23/07/2024

Gill, J. H. 1975. “On Knowing the Dancer from the Dance. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” p 125–135. <https://doi.org/10.2307/430069> Accessed on 23/07/2024

Green, Jill. 2002. “Somatic Knowledge: Green, Jill. (2002). Somatic Knowledge: The Body as Content and Methodology in Dance Education. Journal of Dance Education. 2.” <https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2002.10387219>

Ramaswamy, A. and Deslauriers, D. 2014. “Dancer – Dance – Spirituality: A phenomenological exploration of Bharatha Natyam and Contact Improvisation’, Dance, Movement & Spiritualities”. Intellect Ltd Article. English language. p. 105-122 <https://doi.org/10.1386/dmas.1.1.105_1>.

Schiphorst, Thecla. 2009. “The Varieties of User Experience Bridging Embodied Methodologies from Somatics and Performance to Human Computer Interaction; Ch 2: Embodiment in Somatics and Performance.”. Unpublished thesis manuscript, University of Plymouth.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. 1968. Classical Indian Dance in Literature and The Arts. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Watave, K. N., & Watawe, K. N. 1942. “THE PSYCHOLOGY OF THE RASA-THEORY. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute”. 23(1/4). p 669–677. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/44002605>

Notes

[1] See Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering® (2020).

[2] J. H. Gill, “On Knowing the Dancer from the Dance,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 34, no. 2 (1975): 125–135, https://doi.org/10.2307/430069 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[3] “The dancer is dependent upon the articulation of her own bodily form in such a way that it conveys aesthetically what is intended,[…] the moving bodily form of the dancer is in a very real sense the basis of the dance.” P. J. Arnold, “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 34, no. 3 (2000): 87–95, https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[4] In Indian Aesthetics, abhinaya means the art of expression, i.e., in essence, the art of performance. In Sanskrit, abhi means ‘towards’ and nii means ‘to lead/guide’. In other words, it could be literally translated as “leading (an audience) towards”.

āngika abhinaya (physical expression), comprises the body’s movements, gestures, and postures; here, the study of the technique is of utmost importance; vācika abhinaya (verbal expression), comprises the use of language, including speech, chants, music, and vocalization; āhārya abhinaya (visual presentation), comprises the visual aesthetics of the body, including costume, makeup, adornments, and also scenography.

[5]“[…] as S. J. Cohen points out, that “the audience comes to the dance through the agency of a personality (the performer) who, no matter how hard he may try to be a merely colourless vessel through which the genius of the author is transmitted, somehow transmits a part of himself as well. Furthermore, the more closely he approaches the condition of the colourless vessel, the less interesting the dancer becomes as a performer.”” See P. J. Arnold, “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 34, no. 3 (2000): 87–95, https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[6] Irrespective of whose body we refer to, the performer or the audience, “bodily experience is not neutral or value free; it is shaped by our backgrounds, experiences and socio-cultural habits. […], our bodies are constructed and habituated.” See Jill Green, “Somatic Knowledge: The Body as Content and Methodology in Dance Education,” Journal of Dance Education 2, no. 4 (2002): 114–118, https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2002.10387219.

About the Author

Tejaswini Loundo is a movement art practitioner from Goa, India. As an artist, she is interested in an interdisciplinary approach and intercultural dialogues. Her work explores the intersection of Indian and western contemporary themes and movement arts through an experimental lens. In addition to her dance practice, she is also a creative dance teacher and an aspiring writer. She is trained in Kathak (an Indian classical dance) and western contemporary dance techniques. She holds a BA in English Literature and two professional diplomas in dance: one in Indian Movement Arts and Mixed Media (Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts, India) and one in Western Contemporary Dance (DanceHaus Accademia Susanna Beltrami, Italy). Tejaswini believes art creates a space where the artist and audience can cohesively unify in a shared experience; our existential oneness.