REQUIEM FOR THE FUTURE

In May 1942, Japan dropped the first bomb on Imphal, the capital of the then Princely state of Manipur. The second bomb followed within the week. The Allied British campaign against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan was bolstered by the military, industrial and financial facilitation provided by colonized India.1 The subcontinent served as a base for American operations in support of China, both Allied Nations as well. The Second World War—which was accompanied by heinous events like the Holocaust, orchestrated famines and the novelty of nuclear weapons in combat—resulted in the defeat of the Axis powers and marked the beginning of the Atomic Age.

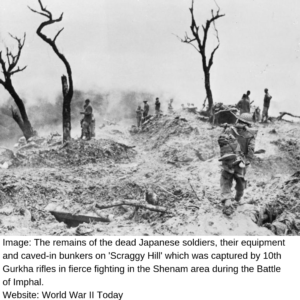

While the residents of Imphal were fleeing their homes, refugees from Japanese-conquered Burma and the retreating soldiers of the British Indian Army were streaming through Manipur en route to Dimapur and Silchar, in what comprised the territory of Assam then. Imphal, being on the frontline of the British-colonised India and the Japanese-colonised Burma, found itself in a precarious predicament. It witnessed a surge in construction of airfields and army bases by the Allies who claimed air superiority in the Burma Theater. After the area was completely cut-off by land, the Allies used their privilege to provide supplies to their troops by air for months on end, while the Japanese soldiers stranded in the area gradually perished. The Battle of Imphal and the Battle of Kohima became turning points in the “South-East Asian Theater of World War II” and the campaign against the Allied Forces. The Japanese Army, which had formed a minor alliance with the Azad Hind Fauj or the Indian National Army under Subhash Chandra Bose, planned on conquering the Indian mainland and cutting off the supply route to China. This mission was named “Operation U-Go.” But the relentless monsoon proved to be a hindrance in the replenishment of supplies, forestalling the Japanese attack. The consequent starvation resulted in the Japanese defeat by the British Indian Army. Had the operation succeeded, the Allies would have faced a devastating blow and history would have taken a different route towards the present day.

Notes

- Auriol Weigold, Churchill, Roosevelt and India: Propaganda During World War II (London: Routledge, 2008).

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), “Imphal and Kohima,” CWGC Online Archives, URL: https://www.cwgc.org/history-and-archives/second-world-war/campaigns/war-in-the-east/imphal-and-kohima.

- Nuclear Engergy Institute, “Chernobyl accidents and its consequences,” NEI Factsheet, May 2019, URL: https://www.nei.org/resources/fact-sheets/chernobyl-accident-and-its-consequences.

- David Wallace-Wells, The Uninhabitable Earth: A story of the future (London: Allen Lane, 2019).