Indian Art in Service of Ecological Activism

AUTHOR

Mustafa Khanbhai

Year on year, the climate crisis grows more pressing, with news headlines about population displacement, frequent natural disasters and species extinction now fixtures of everyday life. Commentators have noted that while scientists, activists and indigenous communities have led movements against the continued deterioration of natural habitats and the commons, political will to address this remains tepid.

The climate emergency demands frameworks that exceed disciplinary silos, and contemporary art’s increasing engagement with ecology reflects this epistemic shift. Recent surveys of climate-oriented art practices have outlined how artists have responded to the planetary scale of the crisis with both localised inquiry and global critique. In contrast to early environmental art, which often romanticised nature or positioned it as a passive site of intervention, recent ecological art sees nature as a politicised and contested terrain. A growing number of artists are dissolving the boundaries between environmentalist and artistic movements, situating their practices within the infrastructure of activism itself. This essay will review recent experiments by artists and organisations to embed art in direct activism, invite the wider public to bear witness to climate catastrophe, and engage in frank discourse on the responsibilities of the artist in an age of collapse. The aim is to explore how art operates not only as a medium of ecological expression, but as a site of material engagement, networked resistance, and the co-creation of alternative environmental futures.

Artists not only comment on social realities but are themselves entangled in the material conditions of global circulation, funding networks, and civic fragmentation. Scholars like Karin Zitzewitz have noted that art institutions — whether commercial or non-profit — often make it a point to carefully gerrymander any practical activism out of the projects they support, framing them instead as matters of logistics, mobility and legibility for diverse audiences. The goal of the NGO is often to make politically engaged, context-specific art easily digestible and globally presentable, rather than deploying it to actively solve the issues it raises. As a result of this not-so-porous border between the black box (or white cube) of the art world, and the noisy, chaotic ‘real world’, meaningful projects often reach only those audiences already supported by the same institutions. Over time, the vocabulary of artistic interventions in the public sphere has become increasingly oriented around institutional appeal rather than relevance to affected communities. Consequently, artists and curators may feel ill-equipped to engage with their subject directly, instead seeking institutional shelter from the consequences of taking anti-authoritarian or anti-corporate stances.

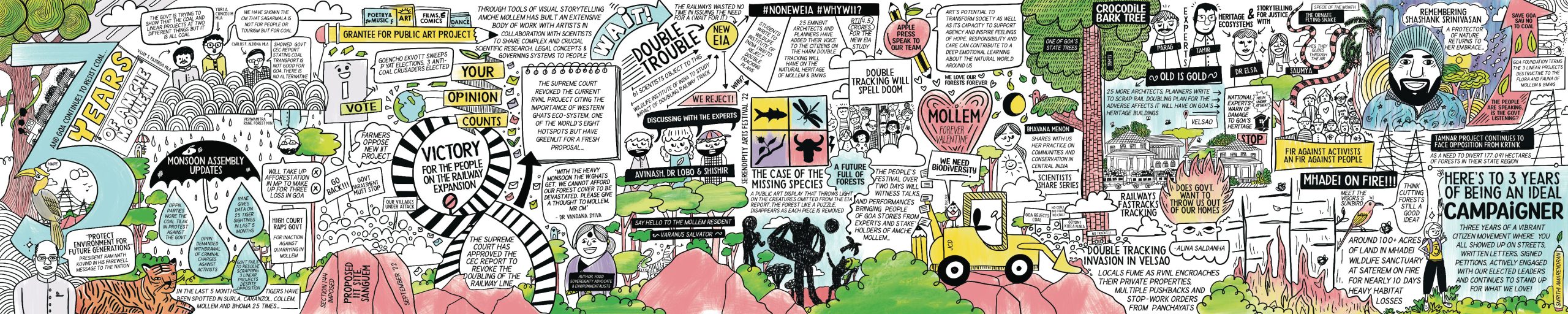

New forms of activism in the digital age have created avenues through which artists can influence public opinion.The Amche Mollem campaign in Goa offers a powerful example of art serving a pressing cause, rather than existing as a sharpened but ineffectually cloistered hobby. Amche Mollem began in June 2020 in response to a government plan to lay double railway tracks and transmission cables in South Goa primarily to move coal through the region. This would have required cutting down large swathes of forest in the Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park, endangering several protected species including some unique to the region. The campaign succeeded the following year, when the plans for the rail were scrapped and the transmission lines were relocated. However, it has had to repeatedly mobilise against similar threats to natural habitats in Goa and other fragile ecologies across India.

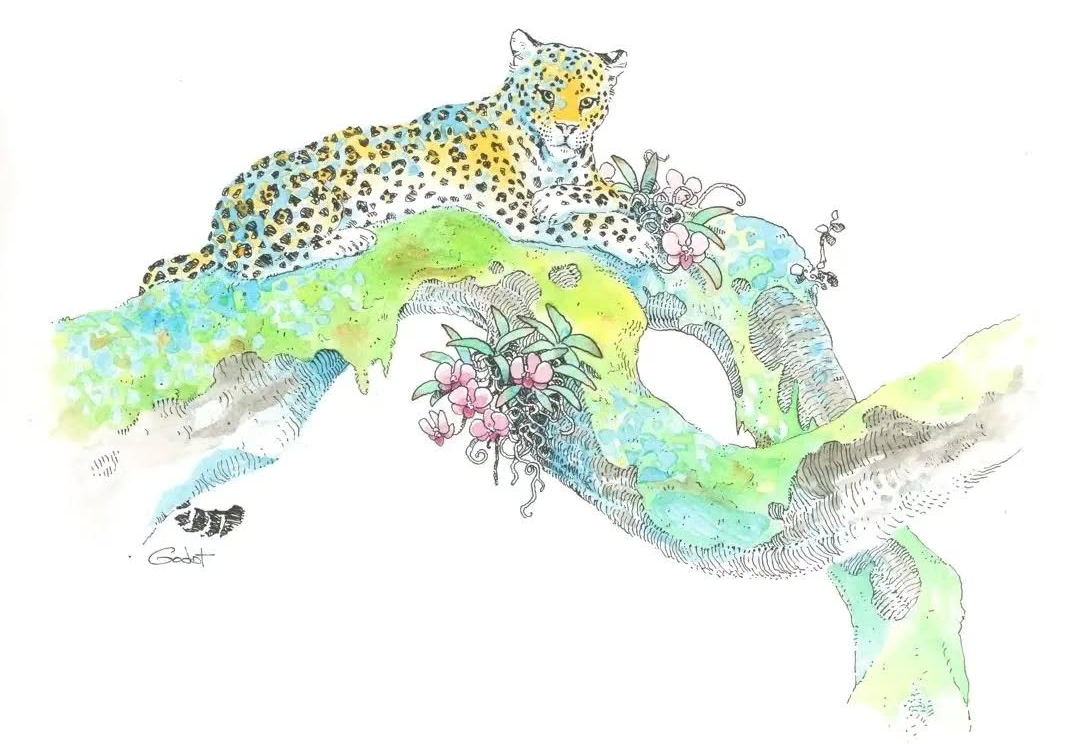

Over the past five years, Amche Mollem has evolved into a kind of para-institution, where legal and scientific expertise converge onto political pressure points, and young artists across Goa, with their otherwise individual practices, have been invited into the movement. Over the past five years, both professional and amateur artists have created and shared work to revive interspecies empathy and kinship among a public that has grown steadily disconnected from the natural world, and has become absorbed into the development-first narrative driving India’s economic and industrial policies. Artists such as Svabhu Kohli, Deepti Megh and Nishant Saldanha have contributed illustrations for social media campaigns and installations at art festivals, depicting endangered species threatened by development projects, explaining complex food webs and migration patterns in Mollem and beyond, highlighting human-animal relationships, and stressing the importance of preserving these natural spaces. While legal support for the movement has come from the NGO Goa Foundation, artistic interventions in the form of workshops and public installations have been facilitated by organisations like the Serendipity Arts Foundation, the Museum of Christian Art and Arthshila Goa, reaching a wide cross-section of residents. By moving through several nodes and forms of engagement, the art becomes completely enmeshed with the activism: functional, organic, and instrumental in translating legal and scientific arguments into accessible visual language.

A less direct yet effective form of ecological art has emerged in recent years through public-facing invitations to witness the climate catastrophe. One valuable example is the 2008 festival 48°C Public.Art.Ecology in Delhi. Artists including Ravi Agarwal, Navjot Altaf, Atul Bhalla, CAMP, Sheba Chhachhi and Krishnaraj Chonat presented interactive, site-specific installations, supported primarily by the Urban Research Group, and to a lesser extent by the Goethe Institut and the Delhi Development Authority. While some projects suffered from shallow engagement or didactic spectacle, 48°C was a landmark undertaking that brought ecological art out of galleries and into the public sphere where artists had to cater to an audience that was almost entirely unconnected to the art world and art discourse. Installations were placed strategically near busy interchange stations along the Delhi Metro’s Yellow Line to attract the city’s general public. The festival’s focus on scale, legibility, and the voluntary engagement of the viewer allowed the works to reach beyond art audiences and create moments of provocation and reflection in urban spaces. The shock value of some installations and the interactive nature of others sparked enough meaningful engagement that 48°C is now seen as an overall positive step in the history of ecological art in India.

While a healthy presence in the public sphere remains crucial for maintaining the relevance of ecological art, it is equally important for artists and the institutions which support them to ask: why do artists matter in a climate crisis? The 2017 performance Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness, organised by KHOJ International Artists’ Association and Zuleikha Chaudhari, addressed this question directly. Framed as a mock hearing on the Indian Rivers Interlinking Project, it featured artists as witnesses being examined by lawyer Anand Grover and defended by Arpitha Upendra. The performance became a Socratic dialogue on the role of the artist as an agent of change. For this reason, Landscape as Evidence: Artist as Witness can be read less as a performance and more as a critical text. It opened up a complex discussion on the role of artists in legal and environmental issues, giving equal space to knee-jerk arguments like those found in Instagram comment sections, and to nuanced commentary on the social responsibilities of privileged artists and the value of empathy over economic anxiety.

What emerges across these examples is a clear call for art to move beyond functioning merely as a site of representation and become an infrastructure of relation. The most potent ecological artworks are those that generate publics, assemble knowledge, and foster coalitions across differences. They do not treat nature as a sublime and distant aesthetic object, but situate it as a terrain of struggle shaped by law, extraction, dispossession and resistance. They help rethink planetary coexistence not through universalising narratives, but through a patchwork of situated, entangled and politically conscious practices.

Bijolia, Disha. 2022. “Inside An Artist-Led Campaign That Saved Goa’s Biodiversity.” Homegrown, October 26. https://homegrown.co.in/homegrown-creators/inside-an-artist-led-campaign-that-saved-goasbiodiversity.

Das, Arti. 2023. “A Future for Forests: Amche Mollem.” ASAP, April 5. https://asapconnect.in/post/552/singlestories/a-future-for-forests.

Demos, T.J. 2013. “Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology.” Third Text, 27: 151–61,doi: 10.1080/09528822.2013.753187.

Fowkes, Maja and Reuben. 2022. Art and Climate Change, Thames & Hudson.

Roy, Sreejata. 2024. “Socially Engaged and Public Art in India: A Chronology from 1990 to the Present (Part 1).” Field, 1 (28). https://field-journal.com/issue-28/socially-engaged-and-public-art-in-india-a-chronology-from-1990-to-the-present-part-1/.

Zitzewitz, Karin. 2022. Infrastructure and Form: The Global Networks of Indian Contemporary Art, University of California Press.