Jonaki – The Birth of Assamese Nationalism

Author

Jahnabi Mitra

The Lack of an Assamese Identity

The efforts to establish an ‘Assamese’ identity have a long history going back to the Yandaboo Treaty. For the longest time in Assam’s history, the Assamese language couldn’t establish its identity as under colonial rule, regulations made it difficult for the Assamese community to organise and fight for its sovereignty. Assamese was long considered simply a ‘dialect’ of Bengali. With a lack of literature and printed material in the Assamese language, the problem of identity quadrupled due to the usage of same script in both the Bengali and Assamese languages. Schools in Assam declared Bengali as a medium of instruction in April 1836.

A contradiction arose from this: ‘If we do not have exclusiveness of language in a territory, how can a language serve as a yardstick of identity for a particular group within a geographical boundary?’1 To do away with this apparent contradiction and to territorialise language, the concepts of language and dialect are invoked and legitimised. This leads to a crucial question: Is it important for a language to have its own script for it to be recognised as a separate language? If so, how could Manipuri establish its separate identity before the creation of the Meitei script and while relying on Bengali as its script?

The Manipuri community went through a similar struggle, where they fought a long battle to revive its lost script Meitei Mayek. Before long, the original script of Manipur was abolished by the King, Pamheiba in the latter half of eighteenth century, who decreed its replacement with Bengali script. The Meeteis2 have been discarding their own script for about 250 years. Thus, despite the efforts seen in late twentieth century to revive the Meitei Mayek script, the community’s complex relationship with the Bengali script persisted. In 1907, when Manipuri was introduced as a mother tongue in lower primary classes there was a decline in the number boys attending schools. Bengali was eventually re-introduced in schools as a consequence.3

Need for Linguistic Identity

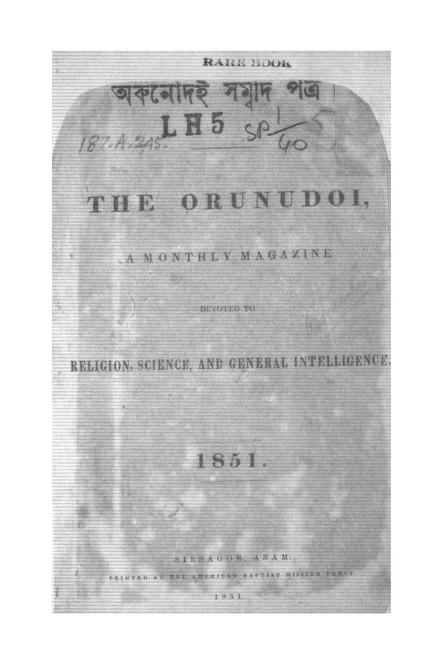

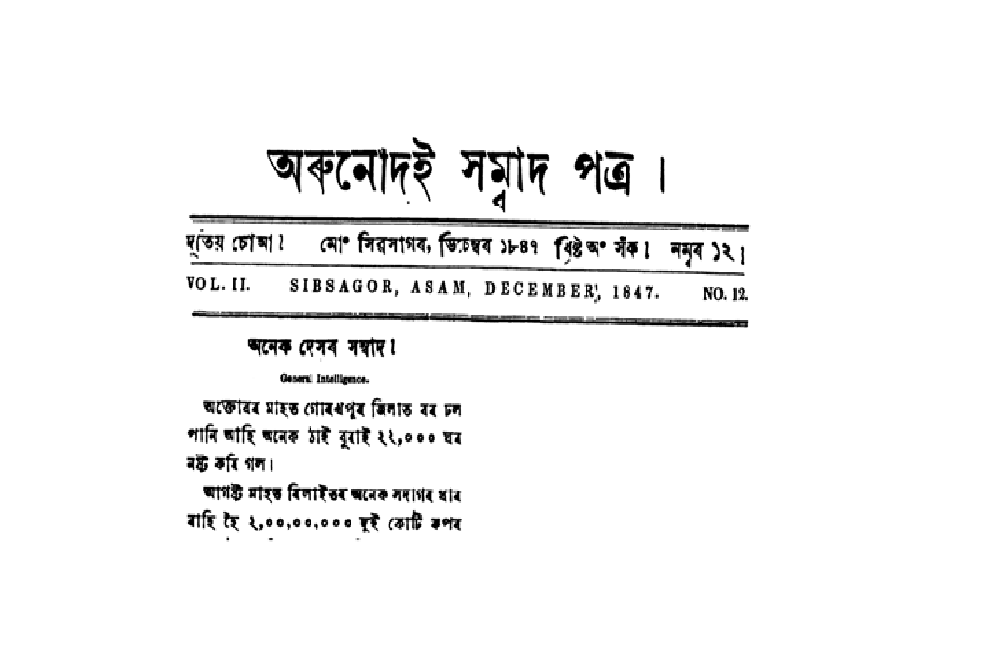

It wasn’t Jonaki that set the tone of print nationalism; rather Jonaki did the job of carrying forward the marshal which was alight. It was rather Arunodoi (pronounced as ‘Orunodoy’), published by Mission Press from Sibsagar that first established the culture of print nationalism. The magazine was backed by Baptist Missionaries in Assam who served as patrons with the agenda of popularising Christianity. Writings on opium usage, opium production in Assam, and development of the West as an outcome of the spread of Christianity were frequently published in Arunodoi. It was understood by the middle-class Assamese intellectual community that the magazine was more of a mouthpiece of the Christian missionaries, yet it helped in unifying the linguistic identity in the region which the Assamese community felt to be lacking until then.

More importantly, it was the ardent need of the speakers of a language-based community to be seen and recognised as separate from the other, dominant language-based community that led to the establishment of Assamese as a formal language.

The official medium of instruction in schools and language in the courts in Assam changed to Assamese in 1873, a restoration after 37 years, and soon after the publication of Arunodoi came to an end in 1883 when the Baptist Mission printing press was sold.4

*

Before Cotton College (now Cotton University) was established in1901 in Guwahati, Calcutta (now Kolkata) was the hub of higher education for Assamese students. What unified these Assamese students in Calcutta was a feeling of alienation and ‘exile’ in a land of Bengali linguistic majority.

In the beginning there were three messes for students coming to Calcutta to study: two Hindu messes, one at 50 Sitaram Ghosh Street and 62 Sitaram Ghosh Street respectively, and another at 33 Muslim Para Lane. Eventually with the increasing influx of students, more messes were added in 67 Mirzapur Street, 107 Amherst Street, 14 Pratap Chandra Lane, Eden Hospital Street mess, etc. Influenced by the western culture of having intellectual conversations in coffee houses, salons were organised in these messes by Assamese students every Wednesday and Saturday. One such tea party at the 67 Mirzapur Street mess on 25 August 1988 took the shape of ‘Axomiā Bhāxā Unnati Xādhini Xabhā’ and the aforementioned tea party converted into the first ever meeting of the literary organisation which eventually birthed Jonaki.

‘Bhāxār bikāx holehe jātir bikāx hobo’ (The nation develops only when the language develops) was the ideological impetus driving the organisation and Jonaki. It had the intent of equalising Assamese language to world languages and standardising its form.

Alternatively, it is understood that students pursuing higher studies in Calcutta were greatly inspired by cultural and intellectual activities in Bengal. For instance, institutions like Calcutta University founded in 1857, Asiatic Society of Bengal founded in 1784, Vernacular Literary Society, Oriental Literary Society, Banga Heet Sabha were working to usher an era of intellectual activity and social recognition.5

Axomiya Bhaxa Unnati Xadhini Xabha decided to publish a monthly magazine which came to be known as Jonaki (The Moonlight). On 9 February 1889, the first issue of Jonaki was published under the editorship of Chandra Kumar Agrawalla. The publication of the magazine aimed to be monthly, yet remained untimely over the years with sometimes having 12 issues a year and at times six or seven. In 1898, Jonaki had only one issue before finally having its last publication from Calcutta in 1899. Jonaki’s publication halted for a year until 1901 when it was revived in Guwahati until its final issue in 1903.6

Understanding the need of the time

What remains relevant for us still, are the recurring themes of ‘linguistic identity’, ‘progress of the community’, and ‘fear of outsiders’. The magazine did not have an editorial, instead it had a segment named ‘AtmoKotha’ (Self-sketch) which portrays the ideology behind Jonaki and Axomiā Bhāxā Unnati Xādhini Xabhā. The very first edition of Jonaki has its objective in what they believed to be the need of the time, clearly stated as:

“Politics is outside our state of affairs. We should concentrate only on the welfare of the subjects of our servile nationhood. Our subject matters will be literature, science or society – we would strive to comprehend these topics and publish materials in them.” It continues: “Objective: development of the nation, and ‘Jonak (moonlight)’…Works are going on everywhere at a crashing speed, will the Assamese sit down idle at this hour?” (Translated by: Uddipan Dutta)7

Further study of the text conveys that the remarks ‘sit idle at this hour’ or shining moonlight has to do with construction of linguistic standardisation and building Assamese nationhood.

The apprehension of the Assamese community of being outnumbered economically and culturally is repeatedly seen in the contributions to the magazine. Critical discussions on how the Assamese community would progress were explored in numerous articles. The very first issue of the magazine published a piece by Kamalakanta Bhattacharya titled ‘Jatiyo Unnoti’ (National Progress). The fifth issue published yet another piece by the same author titled ‘Axomiyar Unnoti’ (Progress of Assamese Community). Eventually, there was a series of essays authored by Bhattacharya from the second till the twelfth issue tited as ‘Axomar Unnoti’ (Progress of Assam). Panindranath Gogoi published a similar piece titled ‘Axomar Unnot ne Abonoti’ (Progress of Assam or Degeneration).

We get a peek into this fear and apprehension of outsiders in Bhattacharya’s essay where he writes: “…The outsiders or foreigners are raking in the wealth of our land. But our store is empty; we do not know what trade is. If someone comes out bravely to do business, his endeavour soon gets fizzled out for the want of determination and perseverance. I cannot say how many days will pass like this. But we can hope that the education would help the Assamese people to learn trade and commerce….”

Is linguistic nationalism possible?

Quite remarkably the need for linguistic nationalism is not something that we saw only in Jonaki. About a hundred years later, Assamese print and television media continues to discuss how to create the Assamese identity and how the Assamese community may survive both as a cultural idea and in terms of population strength. The need to pursue a ‘pure’ linguistic identity has existed in many different communities across history. Yet ironically, linguistic communities which resisted change in grammar and dialect died sooner than the ones which accepted transition in their form. Most modern Indian languages today are spoken in a manner nowhere close to their original form–tracing a long history of shifts and changes.

Periodicals, newsletters, and journals would continue to remain an accessible source that represents the apprehensions and anxieties of a community in its historical context. Words written in periodicals have immediacy, a palpable urgency that books fall short of. It is this that makes them an essential part of enquiring into the past.

The history of print nationalism in Assam follows a long route. After Arunodoi and prior to Jonaki notable attempts were made by Assam Bilasini, Assam Bondhu, Mou, Assam News, etc. The role these magazines played in the creation of Assamese identity is truly remarkable, as even today the history of Assamese literature is categorised in three stages, all named after magazines – ‘Jonaki Age’ (1889–1929); ‘Abahan Age’ (1929–1940); and ‘Ramdhenu Age’ (1940–1970).8 Jonaki is still a popular name across all bookstalls and holds a sacred place in their personal collections in the community, besides striking a chord with many minds in the region; continuing to echo as a clarion call.

Notes

1 Uddipan Dutta, “The Growth of Print Nationalism and The Formation Of Assamese Identity in Two Early Magazines: Arunodoi And Jonnaki”, Sarai Newsletter, July 17, 2007, https://sarai.net/independent-fellowship-abstracts-2004-05/

2 The Manipuris call themselves by the name Meetei or Meitei. Etymologically, the term ‘Meetei’ is derived from the words ‘Mee’ + ‘Atei’, ‘Mee’ means ‘Man’ (person) and ‘Atei’ means ‘Other’, so the word ‘Meetei’ means ‘other person’.

3 Ningamba Singha, “Manipuri Language Movement an its Impact on Education and Eighth Schedule in Assam”, Global Journal for Research Analysis VIII, no. 8, (August 2019): 30–33.

4 Dhruva Saikia, “Assam Newspaper From Brown’s Arunodoi to Sankar Rajkhewa’s The Sentinel“, The Northeast Window, 22 October 2019.

5 Aradhana Saikia Bora, “The Role of Periodicals in Constructing the Literary Culture of Assam: An Overview”, Research Scholar 2, no. IV (November 2014): 182–99.

6 Nitumoni Sarma, “The Role of Journals in the Development of Assamese Literature in the British Period (1826-194s7)”, IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science 15, 3 (2013): 76–7.

7 Jonaki, 9 February 1889, Calcutta. Translation cited from: Uddipan Dutta, “The Growth of Print Nationalism and The Formation Of Assamese Identity in Two Early Magazines: Arunodoi And Jonnaki”, Sarai Newsletter, July 17, 2007, https://sarai.net/independent-fellowship-abstracts-2004-05/

8 Pranita Sarmah, “Impact of Magazines in Creation and Development of Assamese Short Stories”, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) III, 8, no. 06 (June 2019): 45–50.

About the Author

Jahnabi Mitra is a psychologist and an independent researcher from Guwahati, Assam. She is currently working as a faculty member at the Department of Psychology, The Assam Royal Global University. When not teaching, she dabbles in photography and writing. Her photographs have been represented in Through Her Lens- Reframing the Domestic and The Space Without by Zubaan Books Pvt. Ltd. in collaboration The Sasakawa Peace Research Foundation; additionally on 0 print magazine, Angkor Photo Festival and has been Long-listed for Toto Funds the Arts. Her writings have been published by Kitaab International, Café Dissensus, Agents of Ishq, GPlus and LiveWire.