Drawing Dissent: Political Cartoons in Modi’s India

Author

Prabhnoor Kaur

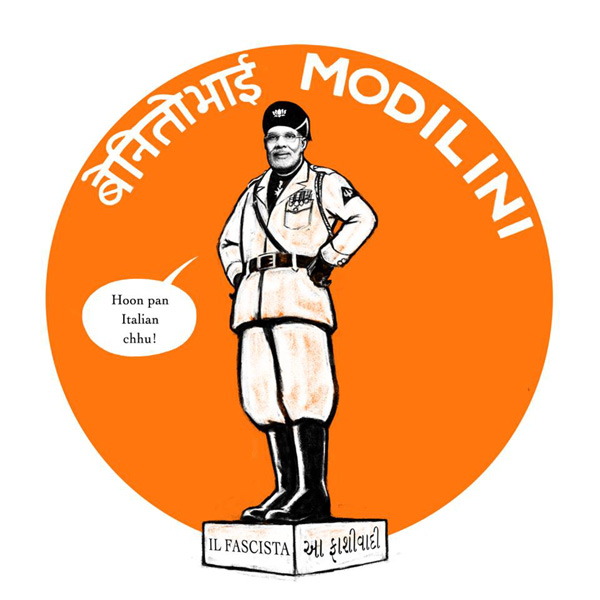

In early 2014, Indian cartoonist and graphic novelist Orijit Sen, angry at the state of this country posted one of his latest works on Facebook.[1] The work featured the face of Narendra Modi on the body of a soldier. The heading reads ‘Benito Bhai’ on one side, while the other says ‘Modilini’, a portmanteau of Modi and Mussolini. The cartoon of Modi claims to be Italian (in Gujarati) while the pedestal he is standing on labels him as a fascist. In a country where censorship is on the daily rise, what compelled Sen to make such a statement? Further still, why share this cartoon instead of simply making his claim?

Political cartoons work along an axis of semiotics, or signs standing in for larger ideas that can be read through the lens of context. These cartoons work in hyperbole – satirising situations and aggrandising characters. Political cartoons are effective due to their use of humour as a tool of reflection on the often dire and depressing realities of our world. Humour creates a sense of community, as it is often a shared experience. In the case of political cartoons, the shared experience is between the cartoonist and the reader, and the shared experience of living in the same context that the cartoon dialogues with. Cartoonist Orijit Sen echoes this thought, ‘At some level, my work uses humour and satire and poking fun as a method – it’s actually a form of distilled anger. […] A lot of work comes out of this sense of feeling hopeless and frustrated.’[2] This approach to use humour to explore deeply heavy subjects effects the core functionality of political cartoons by working along the axis of theories of incongruity, in which absurdity, parody, and humour are used to break patterns of assumption of what is ‘normal’.[3]In this case, by channeling the anger through humour, the cartoonist invites the readers to consider where the punchline lies.

This anger came to a head when, in the midst of a global pandemic, the Modi government passed laws that would open up Punjab’s agricultural sector to the global free market. Farmers that were already under boulders of debt knew this meant that they would be priced out, leading to destitution. Farmers began to speak out against these bills, protesting in their states, yet their voices were not heard. Cartoonist Satish Acharya posted one of his works on Twitter, featuring farmers climbing over a TV set, trying to dig their way into the news that only pays attention to Rhea (Chakraborty) and Kangana (Ranaut). Within the frame of this drawing, we see a sea of farmers behind the television set – calling attention to the number of voices being pointedly ignored. The scaling up of the TV points to the crucial role played by the media in shaping our social consciousness; hence placing importance on the effort to be heard by the farmers by climbing onto a TV set thrice their size.

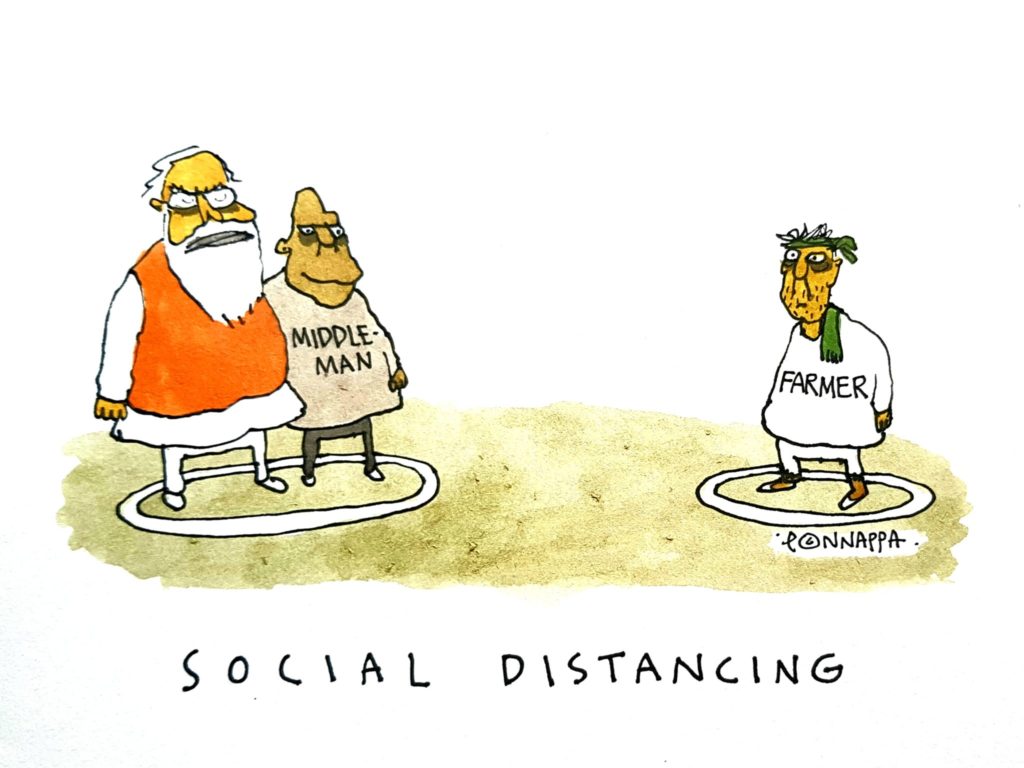

Amid the pandemic, millions of farmers and their supporters took to Delhi to protest these laws. Still, the higher ups refused to meet with them. Nala Ponnappa highlights the irony of this in his cartoon, which shows an exhausted farmer, PM Modi and ‘the middle-man’. This cartoon depicts the PM and the middle-man standing side by side, proclaiming social distancing. Moreover, the middle-man is nowhere close to the middle! Ponnappa’s cartoon with a wink and a nudge makes the reader consider all the excuses being offered for the lack of negotiation.

The farmers occupied the perimeter of the city, blocking highways and refusing to be silenced. The authorities pushed back, constructing blockades and spraying the protestors with water.[4] This protest was the largest worker strike in history, joined by supporters from all across the country and beyond.[5] No concessions were made. Figures from all over the world called attention to the movement, and still no response. As winter sunk in and there seemed to be no end in sight, many farmers lost or ended their lives – a count from May estimating around 500.[6]

A cartoon shared by a Twitter user, signed only with the artist tag ‘Noor’, depicts a haunting image: PM Modi stands addressing a crowd, microphone in hand. The cord snakes behind him and a farmer has fashioned a noose from it to hang himself. Again, there is the same turning of the back from the PM. The cartoon clears that the bells and whistles rung are to distract us from what is happening behind the scenes. The fanfare covering up farmer’s voices becomes the weapon of crime. Over 4000 people liked this image on Twitter, and 6000 retweeted it. Without any words or captions, this image resonated simply through a shared context and timeliness. It implicated those in power without saying anything.

In traditional print media, political cartoons work in tandem with an editorial or text, but with the internet landscape, these images are shared without that supporting context. It is assumed that the person engaging with the work will understand the references, as they are in our internet stratosphere, which often works as an echo chamber, curating feeds to reflect personal beliefs. Within the late-stage attention economy shaped by easy, consumable news bites and Instagram infographic culture, political cartoons are already cut to size.[7] As such, political cartoonists such as Noor can disseminate their work without the reliance on mainstream print culture and receive immediate engagement and response. In the image-proliferated internet, the political cartoon lives as its own entity as opposed to a supplemental point to a written text.

The role of political cartoons is diagnostics, not remedy. By nature, cartoons exaggerate certain details and make wry comments to convey the heart of the issue. For those who are clued into the conversation, are able to make the connections or at least understand the sentiment. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. I would like to return to the Orijit Sen image: the statement Sen is making, of calling Modi a fascist, likening him to infamous Mussolini, is certainly not spoken in isolation. However, the quippy nature of the comment as well as the dichotomy of the image from the persona of the PM (in a kurta and a vest) makes Sen’s cartoon a mainstay in memory. Within the context of the cartoons by the other artists, as well as from lived context, the parallel Sen is drawing does not seem so farfetched. By and large, the role political cartoons play in dissent is to expose the truths about their subject by making them larger than life. Where an editorial examines a situation, propose ideas, and explanations; political cartoons instead act as catalysts to bring to light the reader’s own understandings of the context. In that sense, an editorial can be looked at as a window where a political cartoon serves as a mirror. It pushes the reader to lean in look closer. Under that magnified gaze, readers of the cartoon are able to see the myth-making at work – as Acharya, Ponnappa, and Noor clearly point out, the myth being crafted about Modi is his negligence. It is the refusal of the demands of the country’s people in favor of international corporate interests. The point of political cartoons is to channel anger through a pen, to see the characters through the eyes of the artist, and to do something. They are a call to action.

Notes

[1] Samira Bose, “’Self-censorship is like a termite eating a society from within’: An Interview with Orijit Sen,” The Caravan, December 25, 2015, https://caravanmagazine.in/vantage/self-censorship-is-like-a-termite-that-eats-society-from-within-an-interview-with-orijit-sen.

[2] Kanika Katayal and Bharathy Singaravel, “Orijit Sen: The idea of India is under threat now more than ever,”Indian Cultural Forum, March 29, 2019. https://indianculturalforum.in/2019/03/29/orijit-sen-the-idea-of-india-isunder-threat-more-than-ever/

[3] Dan O’ Shannon, What Are You Laughing At?: A Comprehensive Guide to the Comedic Event (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2012) : 35-37.

[4] Varinder Bhatia, “Explained: Who are the Punjab, Haryana farmers protesting at Delhi’s borders?”, The Indian Express, January 30, 2021. https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/punjab-haryana-farmer-protests-explained-delhi-chalo-farm-laws-2020/

[5]Nitish Pahwa, “Why India just had the biggest protest in world history,” Slate, December 9, 2020. https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/12/india-farmer-protests-modi.html

[6] Anju Agnihotri Chaba, “477 protesters died during six months of Delhi morcha, 87% from Punjab: SKM”, The Indian Express, May 27, 2021. https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/chandigarh/477-protesters-died-during-six-months-of-delhi-morcha-87-from-punjab-skm-7331842/

[7] Jenny Odell, “The Anatomy of Refusal”, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (2019) Melville House, London, 63-95

About the Author

Prabhnoor Kaur is a writer and creative based in Delhi-NCR. She holds a BA in Art History and BA in Screenwriting from Chapman University in Orange, California. Her research interests include print culture and the history of South Asian labor in the West Indies. When not writing, you can find her making fresh pesto from her beloved basil plant.