Karagattam: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

Since the times of Silapathikaram,[1] Karagattam has been extensively practised as an invocation to the village deity Mariamman, to bless the lands with rain.[2] Karagattam literally translates to “pot-dance”. Karagam is a decorated brass pot which is sometimes personified as the deity and is named Sakthi Karagam. Pots with simpler decorations called Atta Karagam are used in dance. Karagattam is accompanied by the spirited folk tunes of Naiyandi Melam.[3] Many folk artists believe that over the course of history, Atta Karagam became a common feature of temple celebrations[4] along with other folk performances.

Image: (Right) Image of Sakthi Karagam (Left) Image of Atta Karagam. Source WikiCommons (Right) | Blog – Local Newspaper in Porur (Left)

In July 2016, the Madras High Court mandated the avoidance of “obscenity” in Karagattam performances.[5] They laid down conditions to be abided if the organizers of such performances wished to host any “Dance and Music” evenings. This essay explores the possible reasons that brought this folk form with over fourteen hundred years of history under the judicial purview.

DUALITY OF KARAGATTAM

Oral traditions indicate that Karagattam evolved from the practice of head priest fetching pots of water for worship at the temple. The delicate act of balancing the pot on their head created the ritual—Sakthi Karagam. Karagattam came into existence when more movements were added to this. Initially, only the head priest danced with the decorated Karagams. Over time, when other male members joined the celebrations, Atta Karagam came into existence. Performers often adapted to the local dialects and a typical repertoire was structured as mentioned below[6]:

- Kumba Attam: Salutations and introductions for the evening.

- Mookaayi Vesham: The artists dress-up as the elderly—dance and talks wisdom.

- Kuravan-Kurathi Vesham: The artists perform as a couple talking about current affairs amongst others.

- Nalla Thangaal Kathai: The main performance commences, usually relating to issues pertinent to social awareness.

- Pei Attam: The artists perform to fast-paced beats, often entering a trance.

- Mangalam – The final performance of the evening, upon which the rituals conclude.

From the repertoires, the Kuravan-Kurathi Vesham (gypsy) gained popularity in small villages across the districts of Tamil Nadu including Villupuram, Madurai, Thutukudi, and Tanjore. The Kuravan-Kurathi dance performance portrays artists as sharp-witted couples discussing current affairs, politics, and social issues. With the increase in audiences’ interests, it became a stand-alone full-length performance.

Image: Image of Kuravan Kurathi Attam | Source YouTube Thumbnail

To ensure that the audience stays for the duration of the performance through the night, it started to become more “entertaining”. Slowly the aspect of dance in the performance receded and it took the form of skits comprising dialogues laced with double entendres*; the dancers interacted with musicians with suggestive insults and flirty conversations*. Over time they also added sexually suggestive and gyrating displays*. The use of karagam and traditional dancing was reduced. The attire of the womxn performers (female and transgender) turned skimpy – shorter skirts, highlighted bosoms, exposed midriffs with a lot of sequins, frills, and sometimes even a decorated headgear. Even though, it should have been called as Kuravan-Kurathi Attam(KKA),[7] the troupes fearing low audience turnout and to secure performances, retained the name of Karagattam.

Current day searches for Karagattam on YouTube shows two distinct forms, unmistakeably differentiating KKA from Karagattam. Typically KKA videos are titled “Very Hot” with sexually suggestive thumbnail images/stills.

Image: YouTube screen grab of Karagattam search results

Erotic Narratives

Image: Image of Kalpa Vriksha as seen in Tanjore Big Temple | Source WikiCommons

Erotic narratives are common in Hindu pantheon—they manifest as sculptures and form a major part of literature. A large part of bhakti poetry has erotic references which, usually is blindsided by those who read/recite them. Through moral judgements and conditioning of “modesty and indecency”, most communities slowly modified and moulded perceptions of eroticism and vulgarity.[8] While eroticism was considered an integral component of Bhakti and of higher aesthetics, vulgarity was cheap and vile. Women in general, were expected to keep their heads low, wear loose-fitting clothes to not expose their bodies, and talk in hushed tones. However, the female KKA performers danced and spoke, unfettered by these notions. The traditional society shamed the performers for being polluted and filthy. Their skin colour, caste and social class made them vulnerable targets and were deemed “characterless and prostitutes”. The normalization of shaming made it easy for men in society to look at them as objects of sexual desire. The society shamed womxn (performers and non-performers) to live in the mould of patriarchy, where female KKA performers were cited as examples of how not to be. Through the shaming patriarchy establishes a structure of power that allows men to get away with physical violence, and sometimes rape that happens outside the performance arena. Instances of violence against these womxn are brushed under the carpet as they are “asking for it”.

The society and audience seemed to forget that the bawdiness of KKA stems from the performance and not the performers.[9] The subtle eroticism over time changed to sexual innuendos, explicit insults, and suggestive acts of varying degrees of raunchiness, which led to a cheering crowd. The form provided comic relief for men, highlighting Freud’s hypothesis that the enjoyment of a joke is connected with what is repressed in a society.[10] The inhabitants of villages saw KKA as a coming-of-age experience for adolescent boys, and normalized KKA performers to be eyed as “things to satiate male desire”. Amidst a patriarchal society, nobody questioned any of this, including the treatment of the performers. The performers had no respect in this society and their privacies were constantly violated.

Audience and Social Encounters

Image: YouTube Thumbnail – Sexually Suggestive and Gyrating Displays | Source YouTube Thumbnail

The audience that KKA caters to is predominantly male—adolescent boys, young, and middle-aged men. The organizers of KKA have clear requirements specific to female body exposure, the number of womxn performers, the duration, and the lewdness of the performance. Each of these factors affect the remuneration. The most respected (powerful/elderly) men in the village preferred not to be seen at KKA, and would promptly leave after the inauguration. These performances did more than just cater to the pleasure of cis-heterosexual men; they were spaces where gestures of power took place. Political parties hosted KKA to entice men to cast the votes in their favour. The performers constantly shamed and shunned, male gaze had driven KKA to the murky depths of misogyny. Despite regular incidents of aroused, drunken men attacking the womxn performers, the organizers take no responsibility of their safety and well-being. These performances, essentially, have become a local Tamil Nadu version of strip-tease without any of the protections extended to those who perform.

Artists

Image: Image of Traditional Performance | Source Pinterest

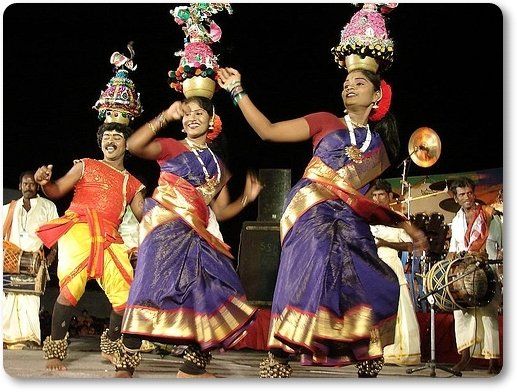

The artists who practise the traditional form are proud of their form, and often do not identify with KKA as a practice. The form of Karagattam has transformed over the years—traditional performers hold their karagam at all times; the female performers wear a saree; they dance and incorporate acrobatic movements during the show, with less or no space for skits. Unlike KKA, the organizers have little say over any aspect of traditional performances.

The artists succumb to the demands of their social world to sustain themselves. Many female KKA performers do not want their children to perform. To distance themselves from being objectified, they call their work as a “service” to lust.[11] Karagattam artists, especially women, receive meagre payments as income.[12] An artist earns up to INR 2000 per performance. Optimistically one performs for 50 nights a year. Even after many jobs, the performers find themselves caught in a cycle of debt. On the other hand, a KKA performer earns more than a Karagattam performer, typically around INR 3000 per performance with more opportunities.[13] Those who perform the KKA are usually related, where they would have started young to earn for the family. Unfortunately, family and economic circumstances bind them to the practice.

Predictably, many artists welcomed the regulations laid by the Madras High court. It included guidance on the timing, content, and attire. It also made the presence of policemen compulsory. While this move is cheered, it dented their income and opportunities to perform. The traditional artists claim that many enter KKA for money and have no Karagattam training. Traditional practitioners choose to remain disassociated from KKA due to its insinuations.

In a nutshell, with most of KKA being performed in interior parts of Tamil Nadu, legal interventions are at best a stop-gap measure.[14] Discussions without judgment and censure, along with active participation of the state government is essential to protect the interests of artistes.[15]

Header Image: (Right) Still from Kuravan-Kurathi Attam (Left) Image of Traditional Form of Karagattam. Source YouTube Thumbnail (Right) | Blog – India Link (Left)

Sexually Suggestive Content

[1] Silapathikaram is among the earliest and crucial texts from Sangam literature (5th-6th century).

[2] Krishnadas, Priya. Folk Performing Arts: Tamilnadu. Chennai, TN: Madras Craft Foundation, 2008.

[3] Nayandi Melam is the musical ensemble which includes percussion instruments – Parai, Udukku, and Thavil, and wind instrument – Nadaswaram.

[4] Temple Celebrations are called Kovil Thiruvizha which occur in the tamil months of Chitthirai (Apr-May) and Aadi (Jul-Aug). The temple celebrations take place through the night with various music and dance performances for the devotees. Depending on the customary practices, the celebrations usually ends during day break with the ritual.

[5] Imranullah S, Mohamed. 2016. “Avoid Obscenity in ‘Kathakali’ and ‘Karagattam’: Madras HC.” The Hindu, July 18, 2016. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Madurai/Avoid-obscenity-in-‘Kathakali’-and-‘Karagattam’-Madras-HC/article14495864.ece.

[6]Dharmalingam, B.,et al. “Dance Formof Karagattam-TheRegional Folk Dance inTamil Nadu.”ShanlaxInternational Journalof Arts, Science andHumanities, vol. 7, no. 1,2019, pp. 71-75

[7] “Plea to Ban ‘Kuravan Kurathi Aattam.’” The Hindu, September 25, 2019. https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Madurai/plea-to-ban-kuravan-kurathi-aattam/article29510912.ece.

[8] NARAYANAN, RENUKA. “Madras HC’s View on Obscenity in Kathakali, Karagattam Seems Obscene.” Daily O, July 26, 2016. https://www.dailyo.in/politics/madras-hc-kathakali-karagattam-south-india-p-devadass-sadir-bharatnatyam-aadi-mariamman-tamil-nadu/story/1/12010.html.

[9] Karthikeyan, Divya. “Karakattam: A Folk Art Languishing in the Web of Morality.” The News Minute, August 1, 2016. https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/karakattam-folk-art-languishing-web-morality-47443.

[10] Henderson, Schuyler. “The Joke and Its Relation to the Unconscious (Review).” https://med.nyu.edu/, March 20, 2008. http://medhum.med.nyu.edu/view/12852

[11] Diamond, Sarah Louise, “Karagattam: Performance and the politics of desire in Tamil Nadu, India” (1999). https://repository.upenn.edu/dissertations/AAI9937718

[12] Basu, Soma. “A Care for Karagattam?” The Hindu, June 11, 2014. https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/society/A-care-for-Karagattam/article11642228.ece.

[13] “Dalit History Month.” Dalit History Month (blog). Medium, April 21, 2020. https://medium.com/@dalithistorynow/swetha-surviving-transphobia-thriving-through-dance-4d25fe67fe21.

[14] “Maridurai vs The Superintendent Of Police on 27 February, 2019,” February 28, 2019. https://indiankanoon.org/doc/128862852/?type=print.

[15] Thanks to Vishwa Bharath (percussionist, folk artist and trainer based in Chennai) and Thanjai G Raju (3rd generation folk-artist who has his own crew in Chennai) for sharing their insights on Karagattam.

Author Bio

Lakshmi Venkataraman is a freelance writer and arts manager based out of Chennai. She has worked on projects with the Prakriti Foundation, the Chennai Photo Biennale and been part of teams at the Bangalore Lit Fest, Nalandaway’s Youth Summit and Fundraiser, BK50, Natya Darshan and other productions/events. She writes content for business houses and start-ups regularly. Her love for stories prompts her to put up flash fictions, and she sometimes dabbles around in poetry as well. Marrying both her passions, she is now exploring art writing.