Building Bodies of Song: Community Singing and Vernacular Song Archives in a Pandemic

AUTHOR

Shruthi Veena Vishwanath

साखी

Sakhi

8:55 AM

(Everyday from 31 Mar to 6 June, 2020)

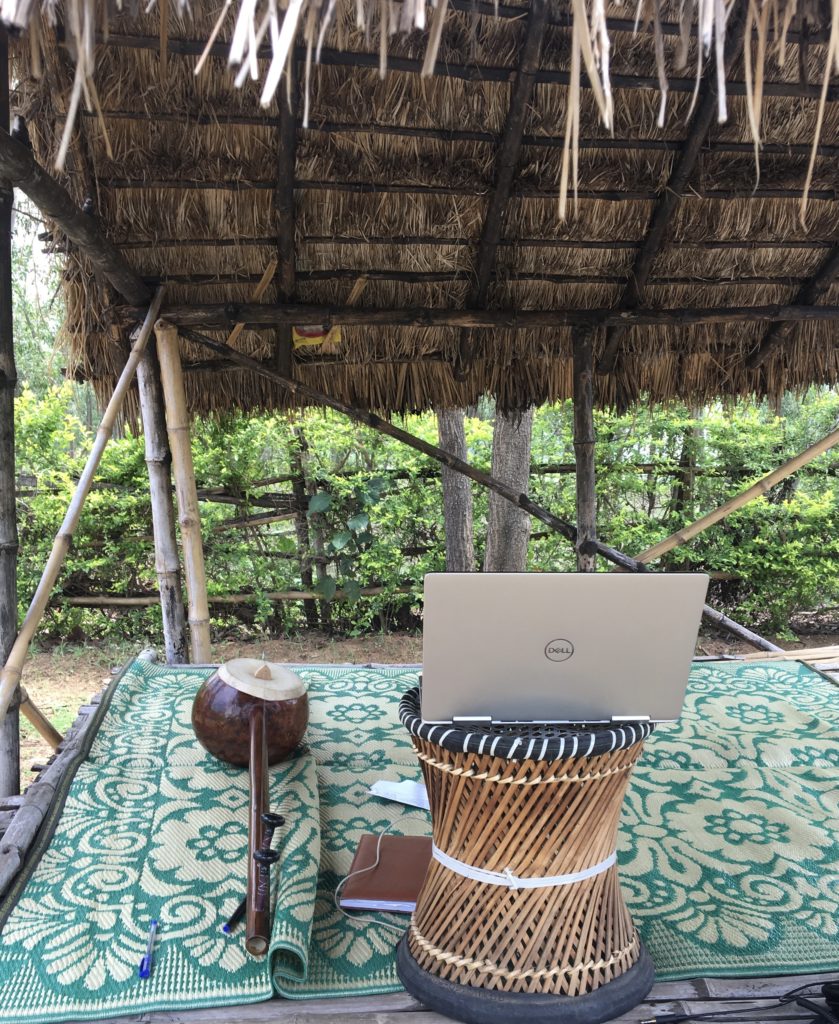

Arshinagar, Gourbazar, West Bengal

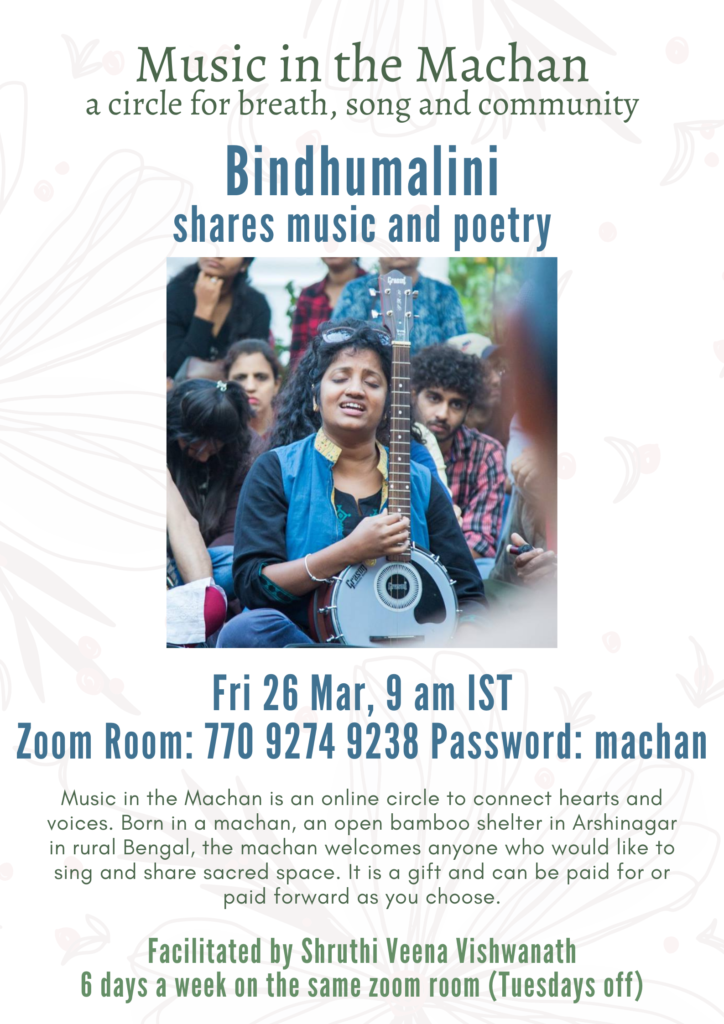

With a bit of acrobatics, I can manage phone, tripod, ektara, bama, ghungroos, all at once. I take them to the Machan, an open bamboo structure in the centre of Arshinagar. Two minutes later, I am sitting on the platform, cross-legged, tripod on the red earth, squinting into my phone to check if the internet gods are on my side. When the home screen clock flashes 9:00, I go to ‘Start Meeting’. Deep breath. Smile. It’s the only concert that’s going to happen for a while. “Good Morning!”

ಗಮಕ

Gamaka

I never believed in online music. My YouTube presence is fairly sparse, my website hasn’t been updated in 30 months. I used to laugh at fellow musicians who said they taught on Skype. But when the pandemic hit, I wondered what I could do in a world full of suffering, and I realised I needed to offer what I knew best: song.

At some point, caught between teenage angst and math tuitions, we begin to forget. The image of the two mountains with the sun and the river disappears from our drawing books, we forget to do a little jig when we are happy, and music becomes the FM channel while stuck in morning traffic. The groove and voice that make us who we are get forgotten with conditioning, pushed deep down into our bodies.

தானம்

Taanam

This has always felt strange to me: I know 6 languages, and yet English is my language of thought and expression. In the other 5, I get called out one way or another. I cannot read or write in my mother tongue, although I speak it. One language betrays my caste markers, I’ve been told. In another, I cannot speak more than 2 sentences without stumbling.

And yet these languages are all me, in delightfully contradictory ways. When I sing these languages, I feel whole. The pronunciation is easy and the changing musical idiom becomes a portal to different parts of me, parts that have been sidelined in my formal education. The more languages I sing in (about 15 more languages currently, from not only South Asia but also Eurasia), the more my body and breath become my own. English then becomes a mere medium for expressing verbally when I have to, and for singing a few songs that I love.

“Till I came here, I always thought that this (regional language) music was very removed from my world. I thought I would never be able to sing like this, sound like this, even though it spoke to me and resonated with me. The Machan has made it really accessible. Of course your facilitation, but beyond that, everyone in the space has helped me out—with pronunciation, with mistakes. I try and feel it and honour the legacy of where this music comes from.”

(Kavya Srinivasan, part of the Music in the Machan community)

আখর

Akhor

A month into this song experiment, I realised that this group of people had the resources to help alleviate the terrible on-ground situation in rural Bengal, where I was locked down for the first three months of the pandemic. A simple call on the group raised enough money to get basic rations for 200 families for 2 months. Song suddenly had power.

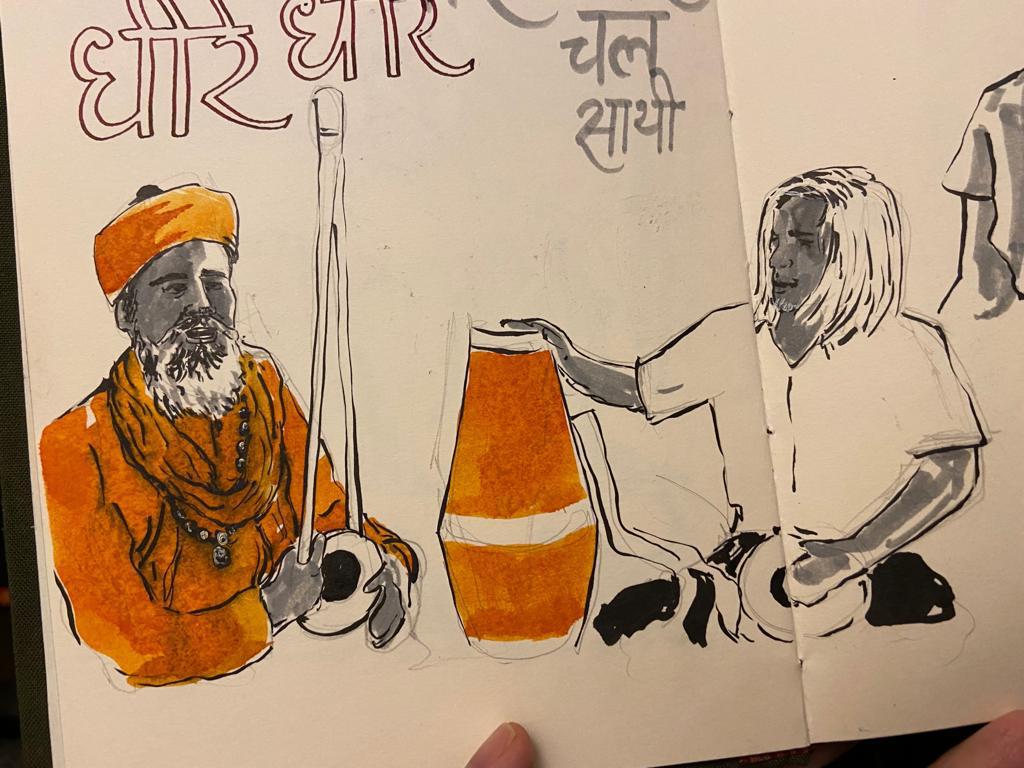

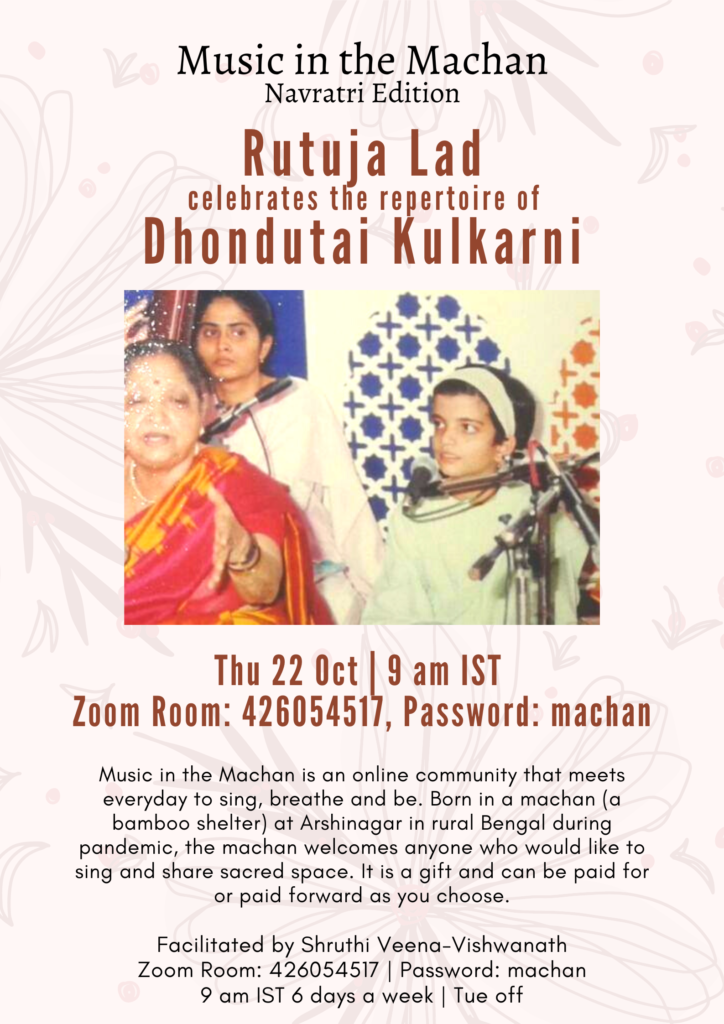

I also wanted to bring guest artists to perform and teach, since all concerts had stopped. I invited my host Uttam Das, a musician with deep knowledge of North Bengal folk, Baul, and Kirtan to teach a song. It was a ‘goshto gaan’ (grazing song) from Gourbazar, the village where we were based. Usually, people teach popular songs, but Uttamda chose to teach something close to his heart. That set the tone.

We had guest musicians once a month. Radhika Sood Nayak with Punjabi Sufi, Prahlad Singh Tipaniya with Kabir in the Malwi style, Vedanth Bharadwaj with songs from MK Gandhi’s Ashram Bhajanavali, Purabi Bhattacharya with Assamese and North Bengal folk songs, among many others. Musicians from West Bengal, the land that most lovingly nurtured this music offering in its early days, tuned in from Gourbazar and surrounding areas. Nemai Das Baul, Netai Chandra Das, Shyamsundar Das Baul came to perform and teach Baul songs. Anathbandhu Ghosh shared Geet Govindam and Vaishnava songs. Mir Basu Barkat Khan, a Mir musician from the village of Pugal, Rajasthan, did a 4-part taught series on Sufi songs in Saraiki and Punjabi.

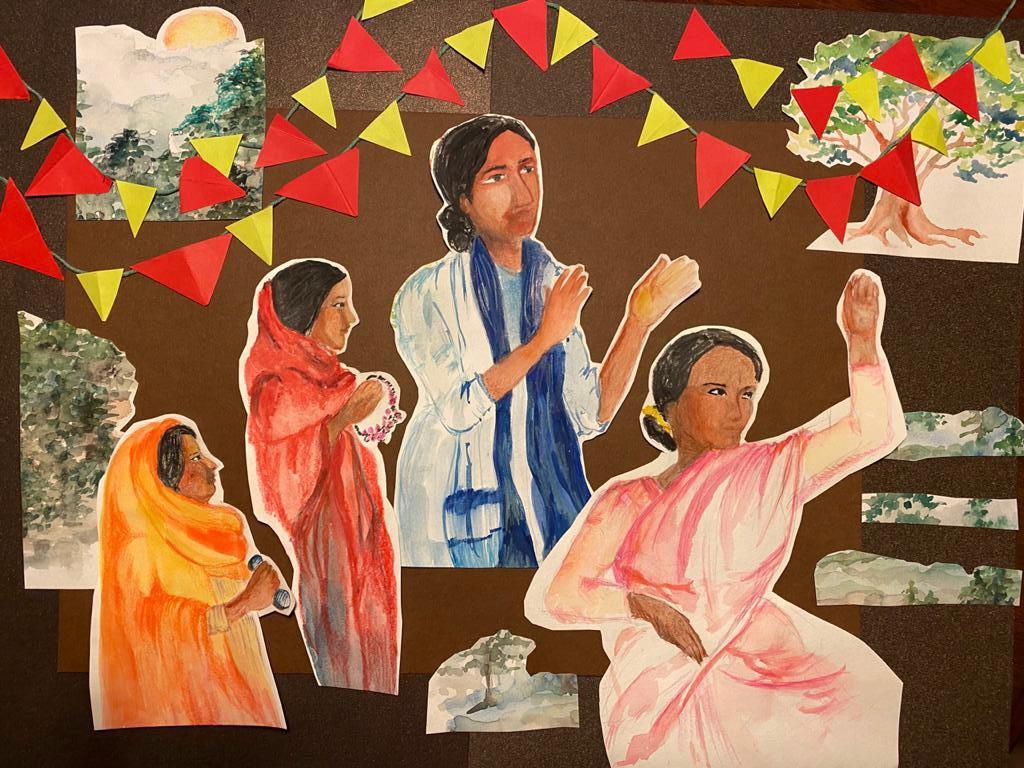

What was critically important for me was that the guest artists also shared their authentic artistic selves at Music in the Machan, and these guests were as diverse as my networks and budget could permit. Rina Das Baul, a rare woman performer in the Baul world, sang one morning and later came to teach. Rafia Biwi, another exceptional woman artist in the Fakiri tradition, came with Tajera Biwi, Nurjahan Biwi, and Nasera Biwi, travelling 9 hours from Murshidabad to Gourbazar, to perform wedding songs. Rafiadi is well known in the region, but the other women had their names on a poster for the first time. Ramakka Jogathi, a wonderful chowdaki player and singer from a North Karnataka community of transwomen called Jogathis, shared her music with us. Shilpa Mudbi Kothakota, herself a brilliant performer and researcher, joined in to support Ramakka with translations.

“Mostly, I am just too shy to sing unless called upon. And yet, the songs stay. So many whose meanings I don’t know, so many that I never imagined would speak to me, and yet the songs stay…”

(Isha Nigam, part of the Music in the Machan community)

जोड

Jod

Singing for an hour a day initially felt like a concert, then later like a public riyaaz session. But soon, I wanted to hear voices other than my own and that of other professional artists. This desire sprang from my belief that we all have a voice and a song waiting to emerge from underneath layers of conditioning.

With time, the community started to sing. Somebody shared a song dear to them, others followed. Then we did ‘rounds’- one song in a session would travel around in a circle (or Zoom rectangle) and everyone would sing a verse or a fragment of the song. Jayaram, a member of the Music in the Machan community, was the one to fearlessly jump in and sing right after me. Others were soon motivated by him, and the fear and hesitation slowly faded. To this day, it is (unspoken) tradition for him to kickstart a round.

My regular co-musicians Shruteendra Katagade and Yuji Nakagawa, accomplished artists on the tabla and sarangi respectively, got inspired and came to share songs. Yuji shared a deeply moving tribute to his guru Dhruba Ghosh, on his barsi. Shruteendra has come several times since to share the compositions of his guru’s father, Dinkar Kaikini. He has even started singing a song or two occasionally in our concerts together, leaving the tabla for a few minutes to use his voice.

“I’ve been assimilating these songs all my life. But suddenly the songs with their layered meanings burst out. Perhaps I needed a platform to share it with people, and the Machan encourages you to speak your true self. I now feel like a bowler who can also bat and wicketkeep! The music in me has deepened…”

(Shruteendra Katagade, tabla player, teacher and vocalist, on Music in the Machan)

خانة

Khana

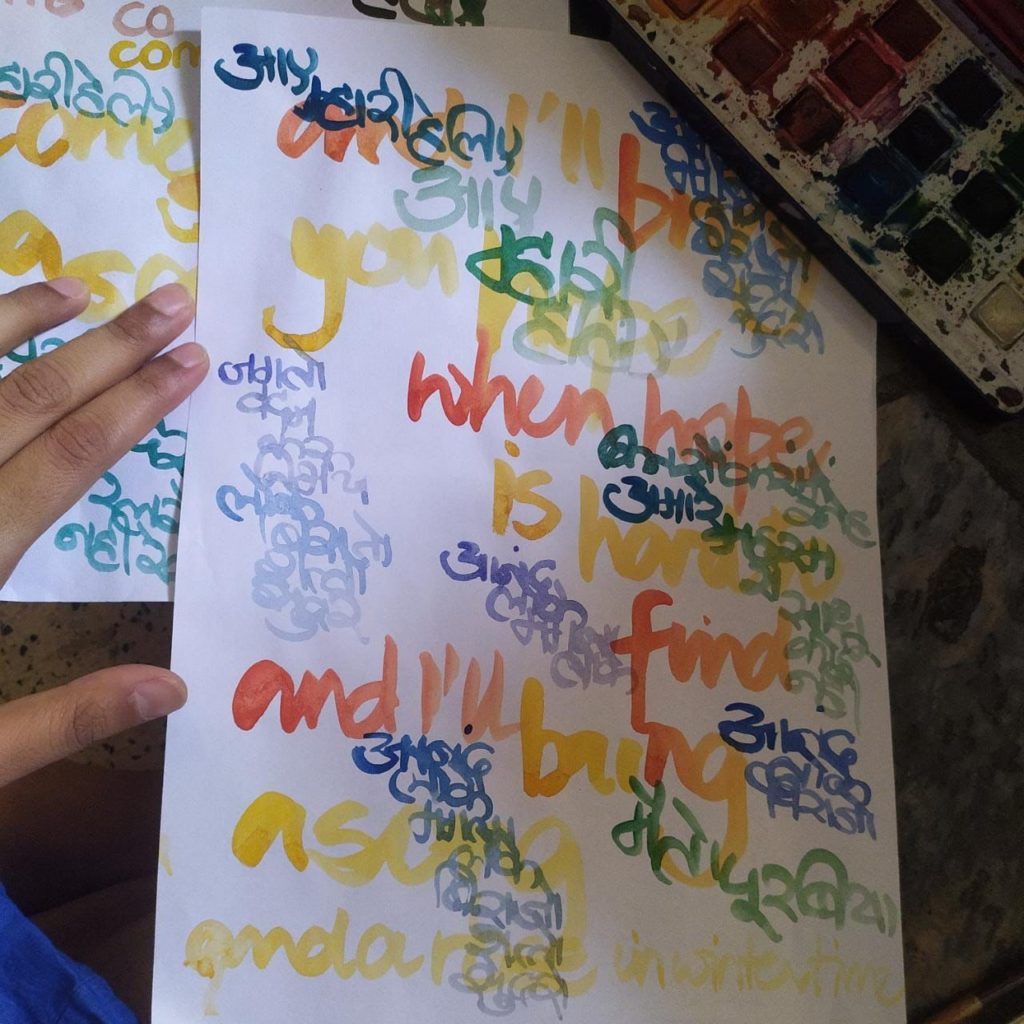

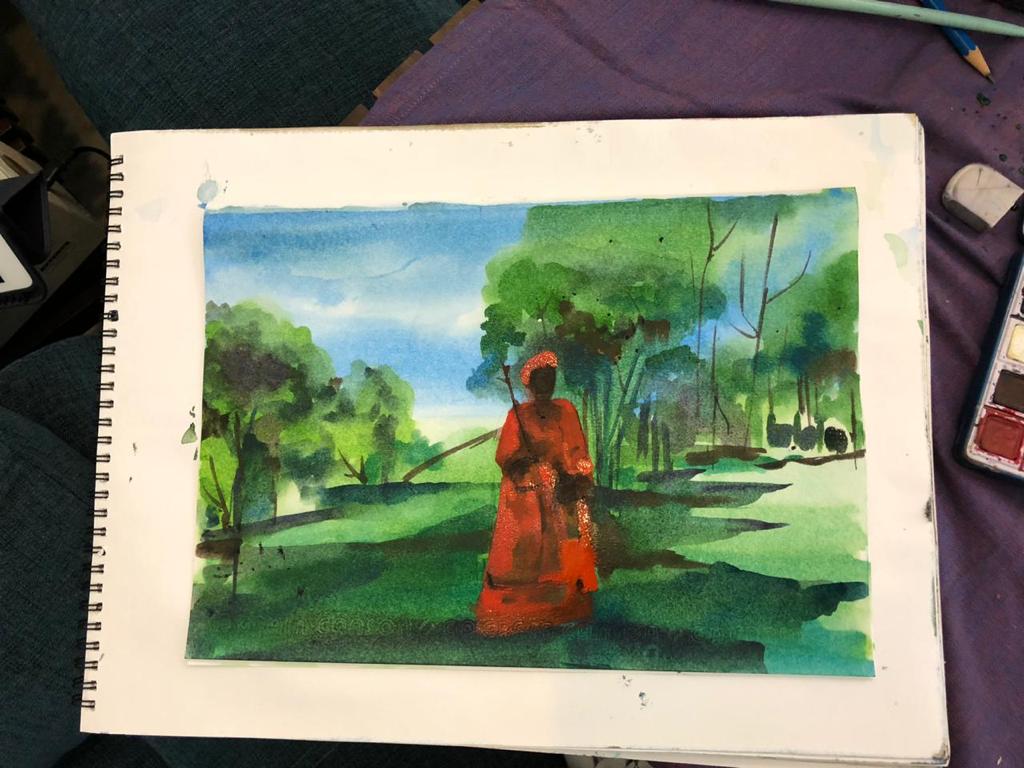

In the early days of Music in the Machan, around the same time that we came up with the name, folks who sang regularly started gently nudging me to record the sessions. As someone who has done hours’ worth of recording at concerts right from childhood, with no patience whatsoever to catalogue and label, I was reluctant. But then someone couldn’t come for the live sessions because they were caring for an aged parent, and I agreed. Sarada and Anisha, two people who have been there since the first day, started recording and uploading sessions onto YouTube as unlisted entries. They also started a shared document to compile lyrics. Several members volunteered to type or translate songs. Keerthana, Adithya, Kaustubh, Aanchal, Veena and others started drawing in response to the Machan sessions.

I had been holding Music in the Machan 6 days a week for 2 years and 3 months, without a significant break. When I got an invitation to tour abroad for 6 weeks, I wondered what would happen to the space. Would it fizzle out? We had had some members of the Machan community lead the occasional session, doing art and song and yoga. We had had some group sessions on the odd day that I didn’t have internet. But 6 weeks?

People took the responsibility of leading the sessions in rotation. Someone would volunteer every day. There was not a single day that the session didn’t happen. I had started and led the Machan, but somewhere along the way, Music in the Machan had truly become a community.

చరణ

Charana

Within any community, disagreements may happen. Music in the Machan is no exception. We are, after all, a microcosm of the fragile world that we live in. But we have tried to work through these conflicts and have had Machan sessions specifically to ensure dialogue. There are times when a song or story shared by someone has made me uncomfortable, and I’m sure people have been made uncomfortable by some of my choices of song or word. When I wanted to share a bunch of guidelines that reflected my personal politics, I was asked by a friend: “Do you want to be in an echo chamber or to create a source of infinite light? Do you want the Machan to only be a space for people like you?”

I didn’t share the guidelines.

The songs we have taught and shared—a majority of them from oral Bhakti, Sufi, Baul, Nirguni, Vachana traditions—have been on the frontlines of our wrestle with questions of caste, gender, and religion for centuries now. That isn’t entirely by accident. While these themes are the central aspect of my personal repertoire, any song circle that has gone on for over 800 days (almost consecutively) needs songs with nuance to thrive. These songs have historically risen from the people. By the people, for the people, always resisting power structures. For the Machan to reach people and truly become a place for embodied songs, we who constitute it need to keep asking difficult questions, within and beyond.

Encore

Music in the Machan meets on Zoom from Monday to Saturday at 9:00 AM IST. The archive of songs, recordings, and lyrics is open to anyone who wishes to access it. The Machan is a gift that can be paid for or forward into the world. Anyone is welcome! Write to [email protected] to know more.

Music in the Machan will have its first offline retreat in Goa in September 2022. It will have guest artists and community singing as well as learning.

Some Guest Musicians

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shruthi Veena Vishwanath (she/they) is a singer, songcatcher, stirrer of herstories, educator and curator. Her practice celebrates mystic music traditions from South Asia and beyond. Their work strives to bring voices that aren’t known, especially women’s, to the fore, and she has composed and researched extensively on various folk, spiritual, and mystic songs from West, South-West and Central India. Trained in classical music for many years, they later dived deep into the roots of mystic traditions, travelling, and learning from traditional practitioners in rural areas. Shruthi has performed at festivals and venues across the world (Jaipur Literature Festival, Rajasthan Kabir Yatra, NCPA, India Habitat Centre, to name a few), spoken at leading universities on music and poetry (IIT Bombay, UC Berkeley, etc.) and received multiple grants for research and performance (IFA, Sahapedia, Gender Bender). She particularly enjoys contextualising music and poetry for young people, and teaches people across age groups. She currently leads an inclusive online community for song-learning called Music in the Machan.

Cover Image: Kaustubh, from the Music in the Machan community