Expected Time of Arrival

AUTHOR

Stuti Bhavsar

With the promise of promptness, Swiggy was accompanied by other food-based apps on my phone with 10– to 20-minute delivery as their USP – BlinkIt with its compression of time into a blink, BigBasket Now, where the now is conceived as an instance, or Zepto, which announces itself as a next-door neighbour with the tagline of being a last-minute app. Today, time as currency has become the most sought-after metric impacting product valuation[1] and our impulsive consumption behaviour[2], as apps shape our perception of which moments are worth cherishing or missing[3], advising the time-starved to save time and spend time otherwise.

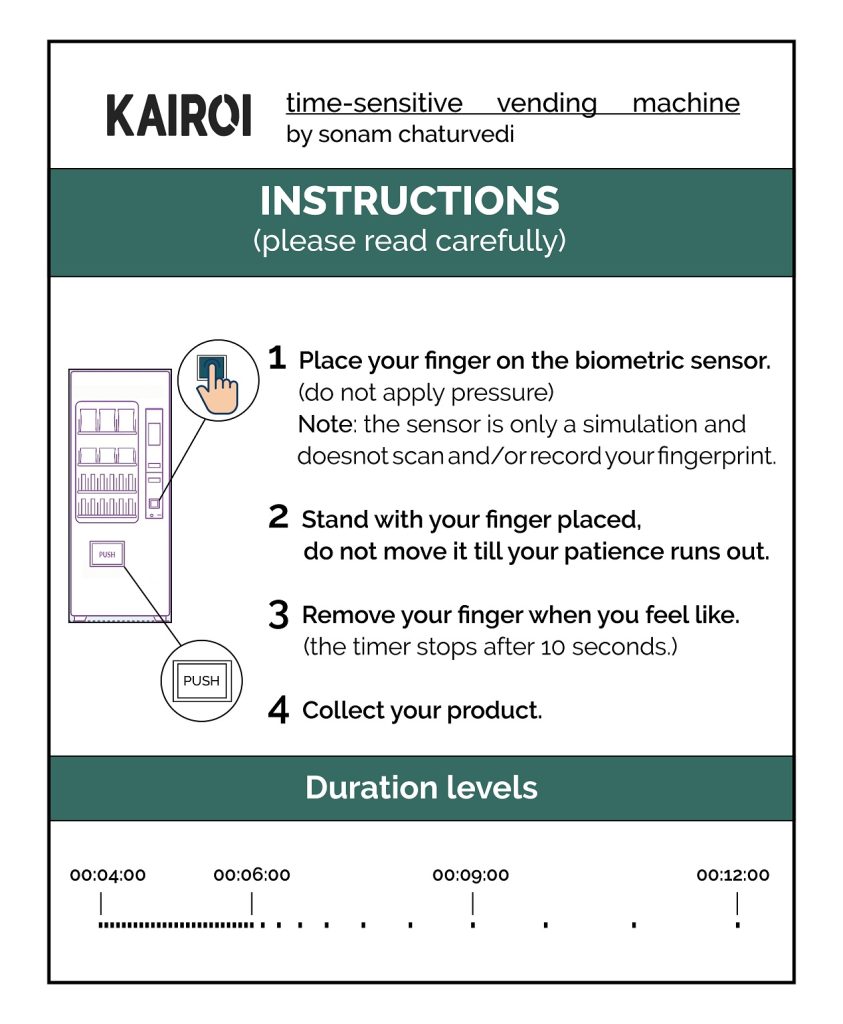

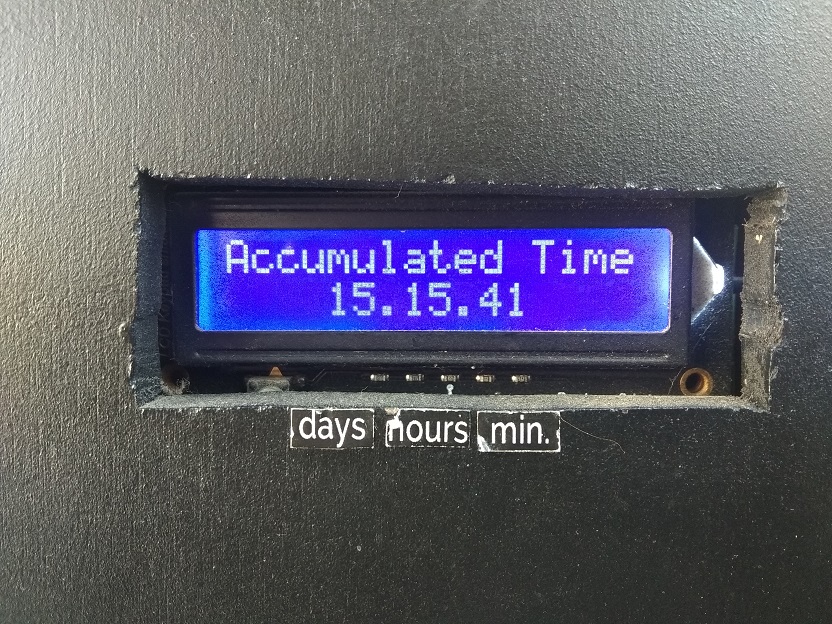

Often located in spaces of transit and stocked with processed foods, vending machines are another such interface—where visuals, marketing, and curated stacks replace the absent store owner and attendant—providing round-the-clock gratification, where convenience is paramount and waiting time is further reduced. Premised on the experiential dimension of contemporary consumption and the ways in which such interfaces shape our dispositions, desires, notions of value, and sense of belonging, this essay looks at Kairoi Times, a time-sensitive vending machine conceived by Sonam Chaturvedi in 2019. Installed near the canteen at Max Mueller Bhavan, Delhi and Kolkata, as part of Five Million Incidents, Kairoi (meaning ‘the times’ in Greek) substituted the monetary value of otherwise free processed food, with waiting time as the currency.

Kairoi at Max Mueller Bhavan, Delhi, 2022. Image source: Sonam Chaturvedi.

Simulating a machine that is commonplace in most urban areas, what intrigued me was Kairoi’s defiance of serving as per expectation, which came to reflect a range of factors that shape our habits, the value we ascribe to processed foods, and the impact it has on the formation of our personal and social selves. With a finger placed on a simulated biometric sensor, the stack revealed familiar but temporally-specific products upon patient gazing. These ranged from Frooti and Uncle Chips, manufactured by Indian industries that were subsumed by MNCs post liberalisation, to imli candies, Natkhat, and Phantom Cigarettes, produced by local small-scale industries, alongside other items in the stack that were manufactured by emerging corporations pre- and post-Independence and which, in many ways, shaped the national consumer imagination.

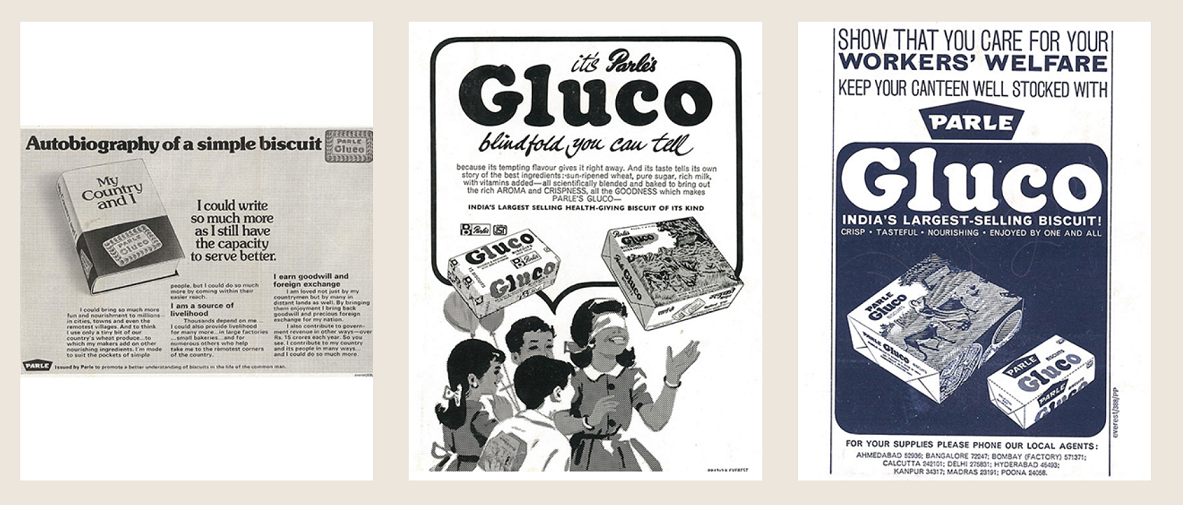

Britannia (Little Hearts, Bourbon) introduced mechanised food production to India and played a key role in supplying biscuits to the British Indian Army during World War II. Parle (Parle-G, Kismi, Frooti, Monaco) was the first Swadeshi confectionery to create affordable Indian alternatives to imported biscuits and candies. Whereas, Nestle (Maggi, Kitkat) was invited by the government to develop the dairy economy post-Independence. In turn, the consumption of products manufactured by these companies became a way to participate in nation-building and serve the values they espoused.

Beneath the products, instead of prices or timestamps, words denoting duration were mentioned, like ‘soon’, ‘simultaneously’, ‘lapse’, ‘longing’, ‘exhausting’, etc. They signified how the computed time didn’t always correspond to its lived experience, where the latter (along with the product’s value) was more often shaped by nostalgia, nutritional promise, access, rewards, and packaging narratives used by corporations banking on hunger.

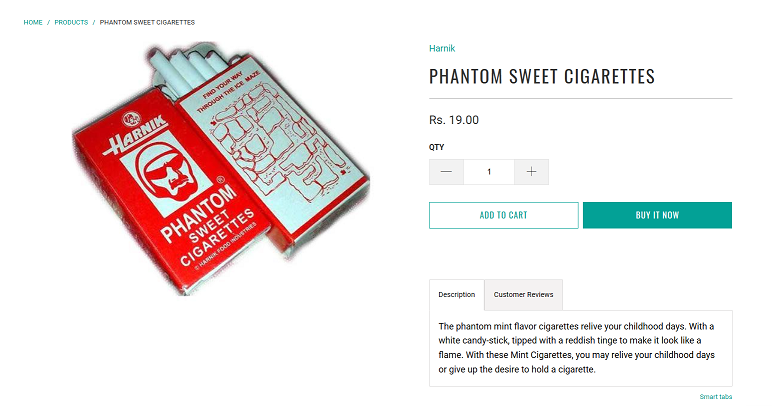

In a conversation with Sonam on the machine’s refill frequency, it was interesting to note how Phantom Cigarettes with the highest timestamps were refilled faster than Parle-G and Little Hearts, with comparatively lower timestamps. These observations reflect that product values are contextual, and as reminded by Neil Cummings, “… (values) are not properties of things themselves, but judgments made through encounters people have with them at specific times and in specific places.”[4]

Parle-G’s availability on the stack and its relevance[5] for today’s youth reflect the mnemonic value through which the biscuit of the masses—made using refined wheat, once a luxury[6] and now a staple—has endured in the market. While its stable price over the last few decades has sustained trust in the biscuit’s nutritional quality and continual accessibility, its unchanged packaging and tagline have served as tools to aid recollection and nurture collective memories. Heavy on nostalgia, its recent advertisement maintains the latter—with decades encompassed within a minute—where its consumption is illustrated to have impacted historical moments within Indian history, to speak to today’s generation about the processes that have gone into shaping their present self.

Accompanied by the crowdsourced #YouAreMyParleG campaign, their trademark ‘g for genius’ personifies professional ethics and success stories driven by moral ideals and resilience, where interpersonal care extends to the nation – continuing the brand’s legacy of being swadeshi and creating a certain kind of cultural conscience. While Parle-G’s consumption reflects embodied values that transcend mere habits, the value of Phantom Cigarettes in the stack is rooted in the difficulty of access.

With their form and packaging modelled after real packs of cigarettes, as a candy, Phantom Cigarettes once offered teens the thrill of transgression, where its aesthetic mimesis lent the item a cool quotient and a glamorous value. Believed to entice[7] young adults into chronic smoking as adults, its semi-ban by the government only strengthened the craving for the candy. Seeing people who remember them patiently wait before Kairoi allowed one to observe how this renewed accessibility also led to the reconsideration of the product’s value. In fact, its current availability through online channels very much attests to its survival despite large-scale withdrawal from grocery shops. This was achieved through careful rewording (sticks instead of cigarettes as in the American market) and repackaging (a substitute for those who’ve quit smoking to fulfil their desire of holding a cigarette), which also facilitated their availability at Kairoi.

Sometimes as an alternative to products stigmatised by society, and other times, as a substitute for products that are financially and socially unattainable, many items in the stack employ mimesis of form and consumption experience, where imitation informs their value. Some examples would be the Monaco biscuit (a snack advertised as the life of tea parties, a colonial consumption context later adopted by the Indian elite), Little Hearts (the Indian version of the local French treat Palmier, now synonymous with being a conduit for all kinds of love), Parle-G (a nutritious, affordable, energy booster and supplement), and Frooti (a packaged drink with a long shelf-life, as sweet and fresh as hanging mangoes).

In the past, the consumption of a few of the above products reflected the emergence of an alternative national identity and a neo-elite public sphere that mimicked colonial tastes and consumption behaviours. Being high in sugar, salt, and fat content, these products also form a larger visual and hunger landscape where the preference for processed foods signals a longing and evokes “the desire to be modern but also appeals to a long-standing sensibility which regards fried and sweet foods as luxuries.”[8] Today, however, as Amita Baviskar analyses, the consumption of otherwise elite snacks in small, affordable packages has paved the way, albeit temporarily and sporadically, for the lower classes and the marginalised to participate in a desired and aspirational modernity.[9]

Although the decision of using small package sizes was a technical and operational one within Kairoi, it demonstrates how buying capacity comes to be built, pushing back against the assumption that processed food is accessible to all classes of society at all times. Moreover, with many corporations nowadays aiming at a 10-minute delivery service for a largely urban audience, the work also questions convenience and how it often comes at a cost borne by delivery persons within a largely unregulated gig economy.[10] Additionally, the machine’s wait time leads to a recognition of the labour behind automated and unmanned food interfaces, and who can/can’t afford the time to take a break, pause, and wait, provoking a critical reflection on emergent consumption behaviours.

About the Author

Stuti Bhavsar is an artist, writer, and researcher currently based in Bangalore. Her interests and concerns are rooted at the intersection of the bodily sensorium, the everyday environment in relation to the historical, and the interaction between a part and a whole. She is also invested in seeing how time and labour manifest spatially, physiologically, and in the conditions generated by interfaces – primarily by probing light as a vector.

Stuti did her graduation in Painting from The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in 2019 and post-graduation in Visual Arts from Ambedkar University, Delhi in 2021. Her essays have been published by organisations such as ASAP|art, Museum of Art and Photography, and Home Sweet Home. Since 2021, she is a copy editor and researcher for Reliable Copy – a publishing house and curatorial practice in Bangalore, dedicated to the realisation and circulation of works, projects, and writing by artists.

Notes

[1]Here, time is meant as delivery time, processing time, and preparatory time, with the latter being quite important within the on-site dining experience.

Singh, Sakshi. “Why kitchen preparation time plays a significant role in food delivery biz”, Restaurant India.in, 2022.

[2] Gent, Edd. “The delivery apps reshaping life in India’s megacities”, MIT Technology Review, 2022.

[3]Through the use of familial, nostalgic, nationalistic, and popular tropes within their push notifications, the apps create an anxiety of ‘missing out’ and mitigate it by providing offers during sports matches, with rewards and discounts during festivals and holidays, or ways one can better celebrate ‘Father’s Day’ with their premium products. Moreover, their everyday personalised notifications around meal times, through wordplay and careful analysis of order summaries, evoke a sense of care and familiarity, where the app purports to remember the consumer’s favourite and check on their needs constantly, just like a loved one would.

[4]Cummings, Neil., Lewandowska, Marysia. “Foreword”, Value of Things, Birkhauser, London, 2000.

[5]However, in the last few years, its relevance—as a product for the masses—for the present youth and whether it will stand the test of time have been questioned. Even as it was marketed as a ‘complete meal’ for migrant workers or as a staple during calamities and crises, the biscuit’s sales have plummeted in the face of competition from other brands with trendier ads, healthier options, and accessibility to gourmet and international range of products (through which one aspires to be a global consumer), with packages drawing upon on more developed reward systems and enticing offers.

Singh, Abhishek. “In a decade or two, Parle will be forced to stop producing Parle-G”, TFIPOST, 2022.

[6]Sinha, Arun. “Why the rich want the poor man’s food”, Free Press Journal, 2023.

[7]Before Harnik started manufacturing Phantom, most of the available candy cigarettes in India were imported. Secondly, the candy’s semi-ban was almost a worldwide movement and so was its later re-packaging and renaming.

Klein, JD., Clair, SS. “Do candy cigarettes encourage young people to smoke?”, BMJ, 2000.

[8]Baviskar, Amita. “Food and Agriculture”, Cambridge Companion to Contemporary Indian Culture, Vasudha Dalmia and Rashmi Sadana (eds), Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[9]Baviskar, Amita. “Consumer Citizenship: Instant Noodles in India”, Gastronomica, 18 (2): 1–10, 2018.

[10]Singh, Karan Deep., Schmall, Emily. “Need an Onion? These Indian Apps Will Deliver It in Minutes.”, The New York Times, 2023.

All references were last accessed on 18 July, 2023.