Grids of Grief: Climate, Caste, and Coastal Memory

AUTHOR

Indhu Kanth

Every grain remembers, each wave forgets…

The sea lives, they say, in rhythms you can almost feel under your skin – a pulse in the breeze, a pattern in the clouds, the subtle pull of tides whispering against your ankles.

For centuries, the Pattinavars1 have tuned their bodies and nets to that pulse: reading the direction of the Vanni and Kota winds2, noting the color of the water. They’ve drawn Kolams3 on thresholds in rice flour to beckon crabs, prawns, and tiny shorebirds. These gestures have been their padu4: a spoken, unspoken code of rotational fishing rights enforced by Oor (village) panchayats with the weight of caste, custom, and collective care.

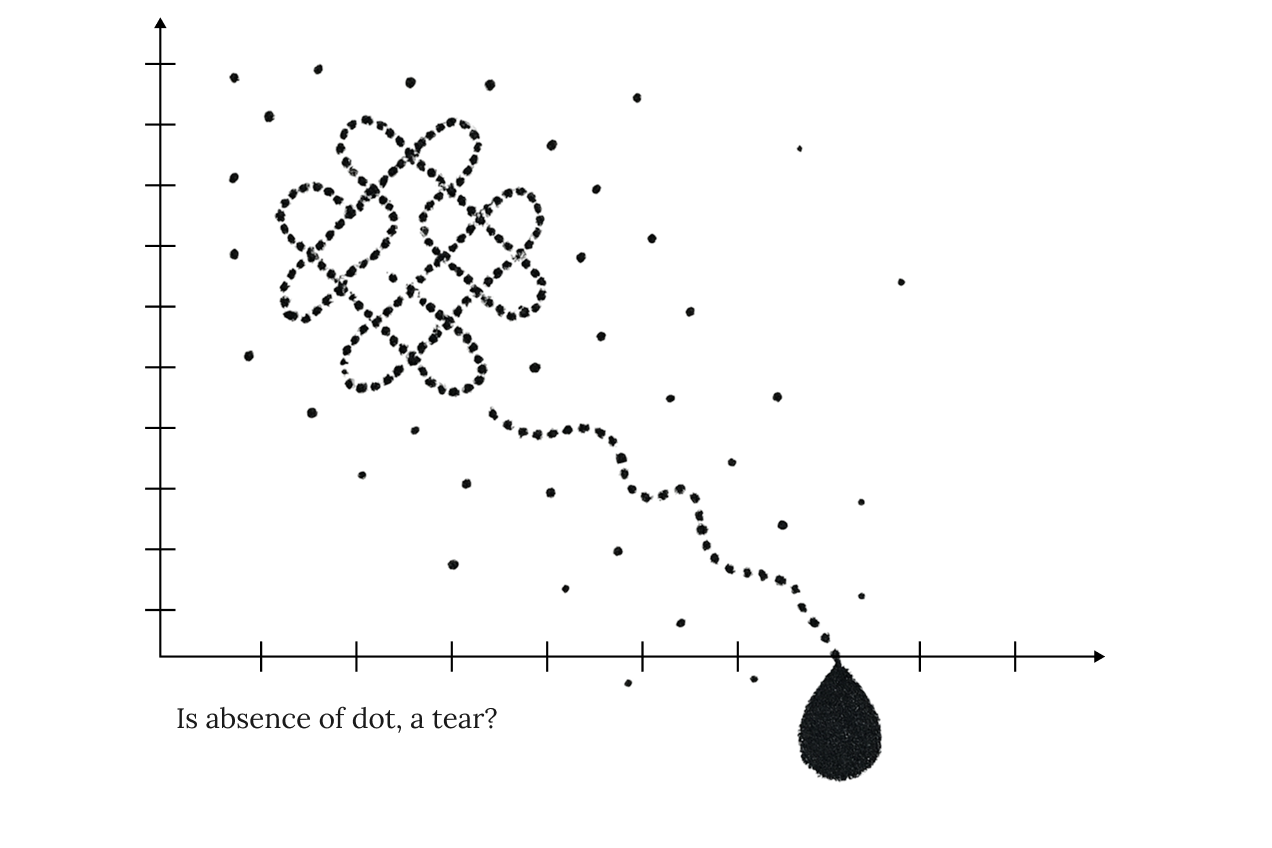

Recently, I walked the Coromandel Coast at dawn and watched women trace kolam in rice flour across cracked concrete. Minutes later, a fishing trawler’s wake washed it away.

I wondered – can we ever TL;DR this grief, this solastalgia?

Trawlers roar in, engines thrumming through Ennore’s mangrove roots. Steel mills dump slurry into once-clear creeks.

What happens when the very air you lean into to predict tomorrow’s catch becomes synthetic? When the young men who used to lash the catamaran to deep-sea currents trade that timber boat for a day’s wage at the steel plant?

The nets come up empty; the kolam dries to chalky silhouettes.

How do you compress the memory of a disappearing ritual, of lore, of a fish shoal that learned to avoid our nets?

Today, those embodied knowledges lie wounded on the beach like half-buried wrecks. The sea’s pulse is practiced only in memory.

We live in a world that wants coastal wisdom in a tweet and climate collapse in an infographic. And in doing so, we’ve engineered away the very thing that makes us human: the messy, beautiful labor of sitting with loss and longing, of letting the sea and its communities change us from the inside out.

I tried to trace the fractures – not only in the coastline, but in the caste-bound padu, in the ritual economy of welcome, in the porous lines between human and more-than-human life.

I ask: how does art emerge when the sea itself is receding?

How do these dwindling rituals become both archive and act?

Once, the sea was our only teacher…

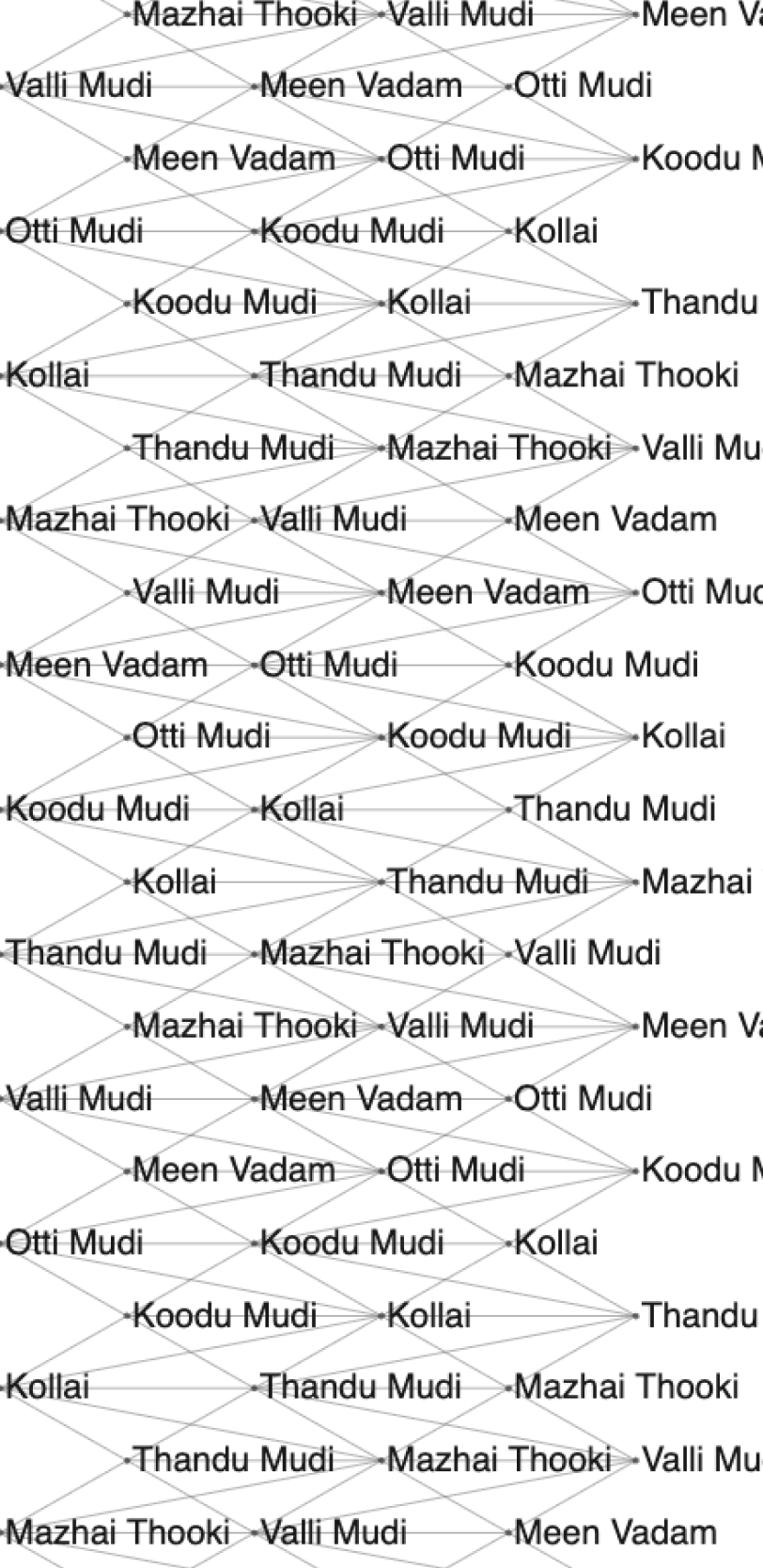

On the Coromandel Coast, a net is more than a net. It is a record of wind direction (vannikai), of sea-current shifts (karai thanni), of fish migrations. Grandmothers had names for every knot (valaichu), every eddy where Garfish (kolameen) gather – teaching grandsons how to plait (kollai) a rope so fine that a single drop of sweat seals the knot.

“You watched the Kota wind rake the water’s surface; you read the Nila jal, that dark blue patch, as a memory of upwelling. You learned that dabjal, the green coconut-water currents, meant lean days ahead.5”

Before fish-finder apps and industrial harbors, the Pattinavars had no choice but to learn the coast’s grammar with their bodies.

“You didn’t grow impatient when your grandfather recited the same fishing saga for the hundredth time, describing tides and moon phases in agonizing detail. You sat cross-legged on the sand because you knew that every telling was both the same and entirely new, shaped by the day’s clouds and your swelling sorrow from the empty nets.6”

Today, we’ve built devices that tell us when valaivicchi (fish schools) pass, then ignore the rituals that taught us to wait, watch, and wonder.

We demand CPUE graphs (catch per unit effort) while the bottom of the ocean pines for its coral.

“My grandmother still tells me how the thalai kattu (the forehead knot) bestowed village membership. I cry every time. Not because the story changes, but because I change. Because each tsunami anniversary, each new chemical spill, makes that story ache differently.7”

But you can’t install empathy like an app update. The waiting, watching, the stammering prayers to Neelatchiamman (Goddess) – that’s their teaching.

Remember when caste was a covenant…

Oor panchayats once wove caste, custom, and care into padu – the rotational fishing rights that kept no one hungry or greedy. The chief’s word was law, but ritual tempered power: fines for chopping mangroves, social ostracism for selling nets to trawlers.

After the 2004 tsunami, those panchayats reactivated padu to allocate relief boats and nets. But the social cracks ran deep.

Mechanized-boat owners – often upwardly mobile Chettiars8 – dominated aid distribution. Widows and Pangali9 families from the lowest rungs got dusty packages, told to wait twelve months. Ostracism hovered beneath speeches about equity.

Youth left for factory jobs. Panchayat meetings emptied. Their rituals went into hiding.

At dawn, women no longer trace kolam in rice flour. Now kolam blooms in acrylics: hard, ornamental, uninviting. Even sacred birds know better than to land.

Communities gather on the strand, tethered to memory, praying to Mariyal (gods of fire and water).They trace symbols in broken rice flour and weep.

These tears aren’t data points. They’re maps with no legend.

Tell me you “get” that, and I’ll ask you to chart the agony of seeing a well or pond dry in April.

And so we drew our grief on walls…

Art on this coast is sprayed on seawalls that crack in the monsoon. It’s pamphlets showing tsunami photo archives stapled to fishing huts. It’s tiny shrines in broken shells and bits of plastic. Out of these fractures, a new canvas emerges.

It is not white-walled nor well-lit; it is sand-dusted and waterlogged. These works embody spatial and emotional metaphors of fragmentation. Grids of grief appear in both tactile and digital realms. They demand viewers navigate a fractured visual field – part archive, part action.

Kolam Festivals & Guided Kolam Tours

In many Tamil coastal regions, collaborative kolam festivals invite participants – youth and outsiders alike – to co-create intricate patterns while discussing community histories and local environmental change. A few organizations offer guided tours for visitors to observe and honor such festivals and practices.

Kannagi Nagar Murals (Chennai)

After the 2004 tsunami, the resettlement colony of Kannagi Nagar became known for its large-scale murals. Artists, many from fishing communities or with strong coastal identities, have transformed walls into visual storytelling canvases exploring themes of survival, memory, resilience, and hope after disaster.

Wetlands Celebration (Pulicat)

World Wetlands Day is observed annually as “Pulicat Day,” featuring catamaran races, ecology quizzes, kolam competitions, and folklore performances. These events weave together ecological conservation and cultural memory, and often see fisherwomen and children as lead participants. Over 120 fisherwomen have been empowered through palm-leaf crafts, linking traditional creative labor to environmental protection and new economic pathways.

Speculative Futures: Repair or Rewilding?

This is not romantic nostalgia.

The sea is receding – scientists warn 30 cm by mid-century. Art cannot paper over these wounds. We must practice a “radical remembrance”.

Seeing kolam lines not as pretty motifs but as calls to cross-pollination; Hearing nets not as loss, but as living archives of weather lore. Knowing that every eroded dune holds a caste story, a mangrove prayer, a forbidden padu tale.

What happens when we invert the gaze?

Can we imagine a kolam drawn by drones scattering seed-bombs of mangrove propagules? Or padu enforced by blockchain contracts, granting rotational rights visible on GPS-mapped chairs?

If art is to be resistance, it must dissolve the walls between gallery and gutter, between padu and protest.

We must draw sketches in sand that outlive the tide – by sparking uprootings of institutions, of industrial investments, of extractive mindsets.

But if we refuse to pause – if we never linger with a story for longer than a scroll – we’ll become creatures of surfaces, skimming endlessly yet never drowning in depth.

Unlike the 24‑hour news cycle, the sand in our shoes and the salt in our hair remain. They linger.

Next time you are near a shore, press your feet into that shifting sand.

Feel the pulse. Just pause.

The next time you see kolam, don’t just photograph it. Offer a handful of rice. Stay a while. Let the tide claim your footsteps.

Because that is the real story:

We’re not here to summarize or compress lives, but to live them – in all their blur and beauty, in all their raging seas and ritual lines – until we learn to draw life again.

When the sea is receding, all that remains is what we choose to draw and who we choose to feed.

Notes

- Pattinavars are a maritime Tamil community primarily found along the Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu, India. They are traditionally involved in fishing, seafaring, and trade. The term “Pattinavar” itself means “inhabitant of a port town”.

- The Vanni winds are locally known as seasonal, dry winds associated with the dry season. These winds tend to come from land masses and are hotter and drier. They influence local climate and agricultural cycles but are not as strong or regular as monsoon-driven winds. Kota wind is used regionally to denote strong, seasonal winds that funnel through mountain passes or coastal gaps. These winds can be associated with the monsoons or the transitional periods between them.

- Kolam is a traditional South Indian art, mainly in Tamil Nadu, featuring intricate geometric and curvilinear patterns drawn at home entrances. Made with rice flour, chalk, or colored powders, kolams are believed to invite prosperity, welcome guests and deities, and serve as a ritual offering to non-human life like birds and insects.

- The Padu system is a traditional method used by fishing communities in India, particularly in regions like Pulicat Lake and Vallarpadam Island, to manage access to fishing grounds

- Romayas, 38, second‑generation boatman from Vizhupuram.

- Murugesan, 67, Pattinavar elder of Nagapattinam who still reads tides by hand‑made charts

- Lakshmi, 46, fisherwoman from Cuddalore whose childhood revolved around granddad’s stories.

- A prominent mercantile and banking community from Tamil Nadu, traditionally known for their wealth, business acumen, and social influence. Many Chettiars belong to higher caste groups and are often upwardly mobile, owning mechanized boats and controlling local economic resources.

- A historically marginalized community in Tamil Nadu, often associated with lower caste status and traditional occupations considered “polluting” or outside the mainstream social hierarchy. Pangali families frequently face social exclusion and economic vulnerability.

- Velvizhi, S., Thamizhazhagan, E., Suvitha, D., Mubarak Ali, A., Arokiya Kevikumar, J., Lourdessamy Meleappane, C., & Fish for All Research and Training Centre, M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation, Poompuhar, Tamil Nadu. (2021). INDIGENOUS TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE OF FISHER FOLKS IN MANAGING THE OCEAN STATE CONDITIONS, WEATHER VARIABLES AND FISH AVAILABILITY – A STUDY FROM TAMIL NADU AND UNION TERRITORY OF PUDUCHERRY [Journal-article]. World Journal of Pharmaceutical and Life Science, 7(5), 57–65. https://www.wjpls.org/admin/assets/article_issue/65042021/1619693600.pdf

- Raja, Selvaraju & Rajamanickam, Geetha & Kizhakudan, Shoba & Vivekanandan, E. (2014). Traditional Knowledge among fishers of Coastal Tamil Nadu with special reference to Climate Change. 10.13140/2.1.1195.0722.

- Rathakrishnan, Tr & Ramasubramanian, Muthuramalingam & Anandaraja, Nallusamy & Suganthi, N. & Anitha, S.. (2009). Traditional fishing practices followed by fisher folks of Tamil Nadu. Indian journal of traditional knowledge. 8. 543-547.

- Balasubramanian, G. The Role of Traditional Panchayats in Coastal Fishing Communities in Tamil Nadu, with Special Reference to their Role in Mediating Tsunami Relief and Rehabilitation Contents.

- Muthupandi, Kalaiarasan & Neethiselvan, Neethirajan & Gayathre, Lakshme & Mariappan, Sangaralingam & Ragavan, Velmurugan & Kalidoss, Radhakrishnan. (2024). Indigenous fishing gears of the Pulicat lagoon of Tamil Nadu. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 23. 583-593. 10.56042/ijtk.v23i6.11830.

- Bavinck, M., Vivekanandan, V. Qualities of self-governance and wellbeing in the fishing communities of northern Tamil Nadu, India – the role of Pattinavar ur panchayats. Maritime Studies 16, 16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40152-017-0070-8

- Madhanagopal, Devendraraj & Pattanaik, Sarmistha. (2020). Exploring fishermen’s local knowledge and perceptions in the face of climate change: the case of coastal Tamil Nadu, India. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 22. 3461-3489. 10.1007/s10668-019-00354-z.

- FSS:HEN612 Traditional Ecological Knowledge Systems. https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/podzim2011/HEN612/um/26486599/