How Many Lives Does A Fruit Live?

AUTHOR

Shankar Tripathi

It was always the smell that first caught my attention. A smorgasbord of musky vapours, the room would be filled with its wafting hints of banana, pineapple, and rotten onion. Riveted to the ground, I would find myself carefully examining its cleft parts, wondering how the scent of something so familiar – a fruit that has nourished civilisations for thousands of years (and countless dinner conversations about my nutritional intake) – could feel entirely alien and distant. Ironically however, I found this all-pervasive miasma enchanting as well as nauseating, and remember being mesmerised by it when I first encountered Sajeev Visweswaran’s works.

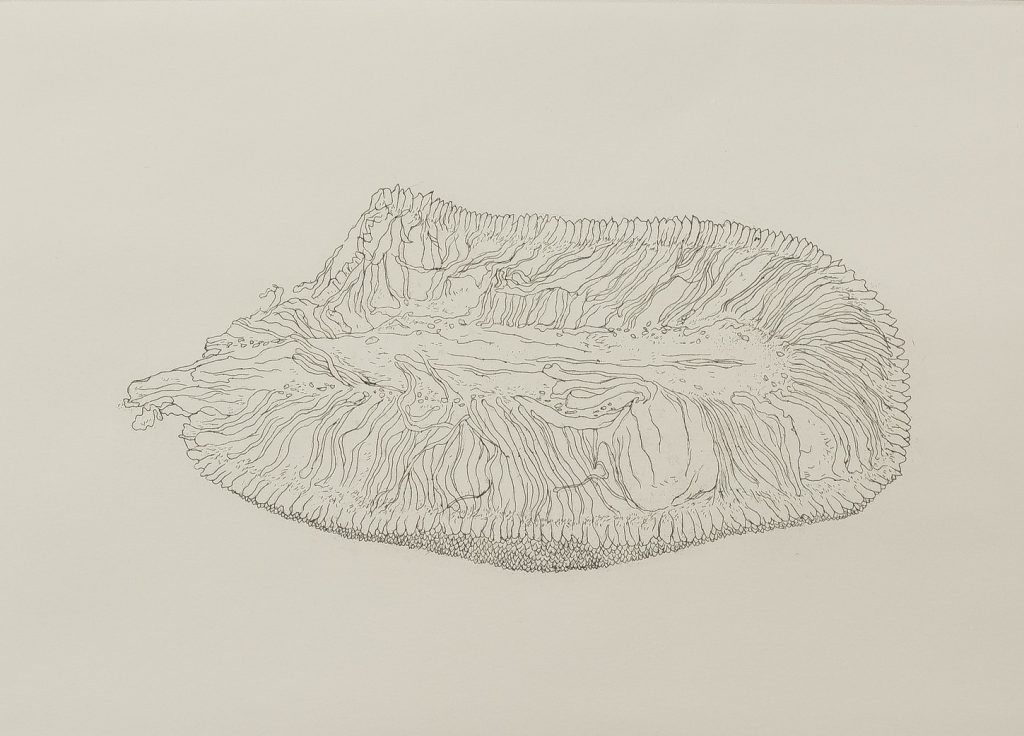

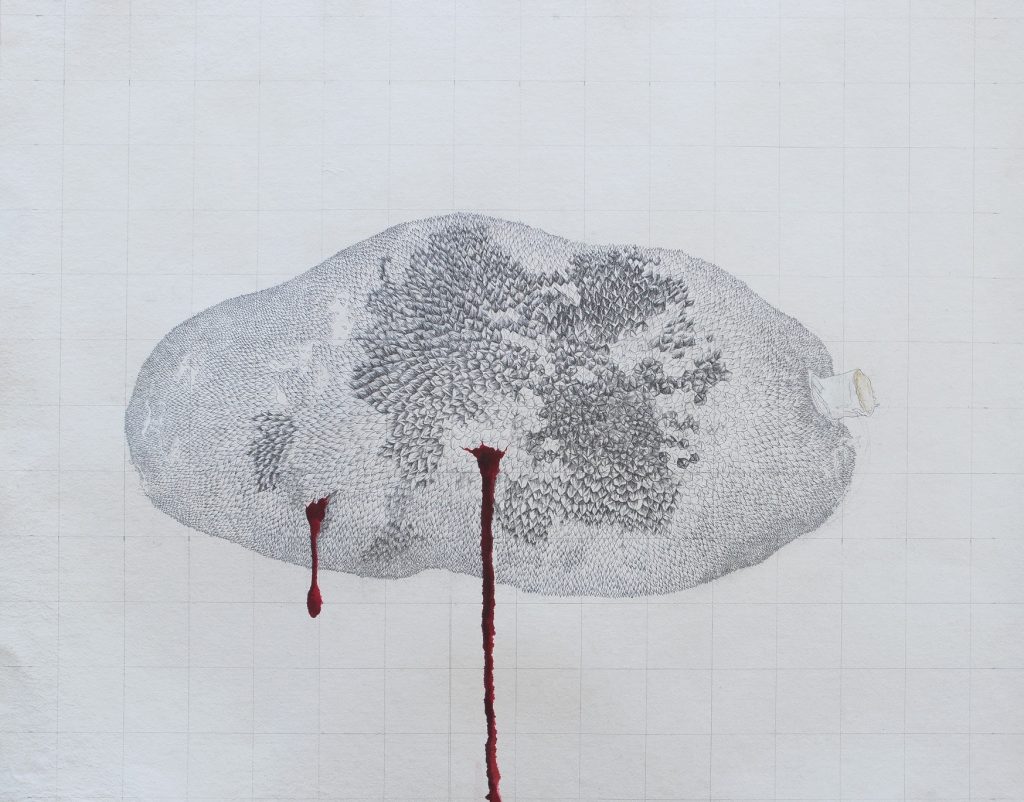

Coming infinitely close to its exposed, fleshy sinews, I saw Sajeev’s hand meticulously trace every rhizomatic connection in front of him, not once leaving the trail of fibrous networks that lay severed from the fruit. His clinically precise lines felt measured and composed, detailing centuries of dietary evolution with delicate profundity. Sajeev’s surgical dissection met no resistance – his pen gliding effortlessly over the paper, registering intricate layers of its reality. In looking at his drawings, I was witnessing his deliberate attempt at removing cells upon cells, noise over noise, till what one was left with was the cleanness of a line.

To look at Sajeev’s works thus meant witnessing his event, a transformative moment in the structure of his work – a deconstruction, if you may – where he bled out colour and context, freeing the object from the grasp of all things temporal and spatial. By his hand, in sieving out the tiniest of bumps and the most wayward of lines, a wholly impersonal, innocuous, and seemingly innocent object was transformed into something real, personally felt, and tangibly appreciated. What I found most interesting was that in observing the universality of his line – its cold, calculative, anatomical estimation – I spectated on the particularity of Sajeev’s experience. His two-dimensional visuality suspended the object, distancing the viewer and yet bringing to the fore the totality of its direct circumstance. I saw his meal, and hungered for my sustenance.

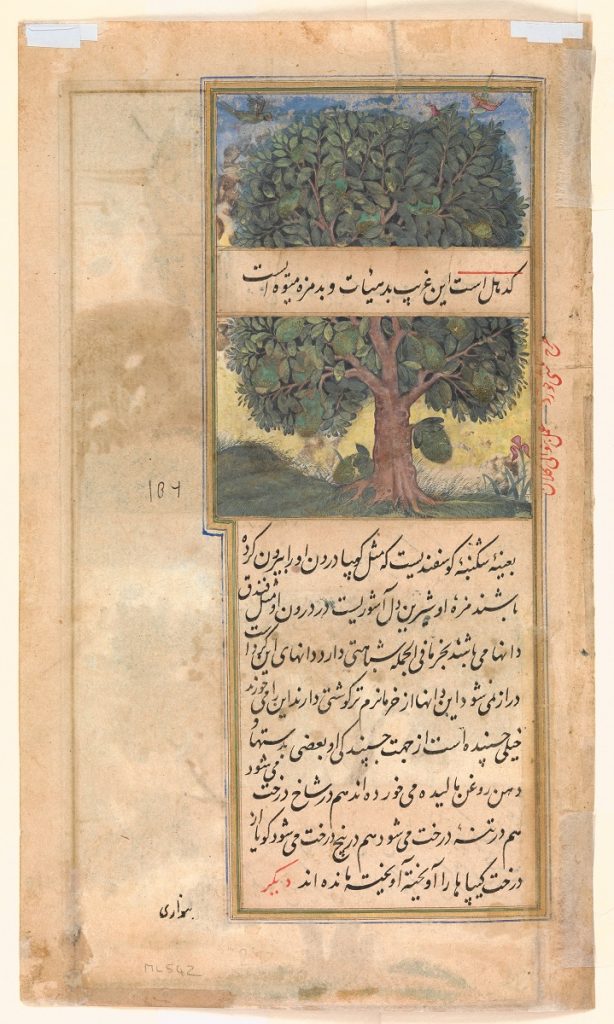

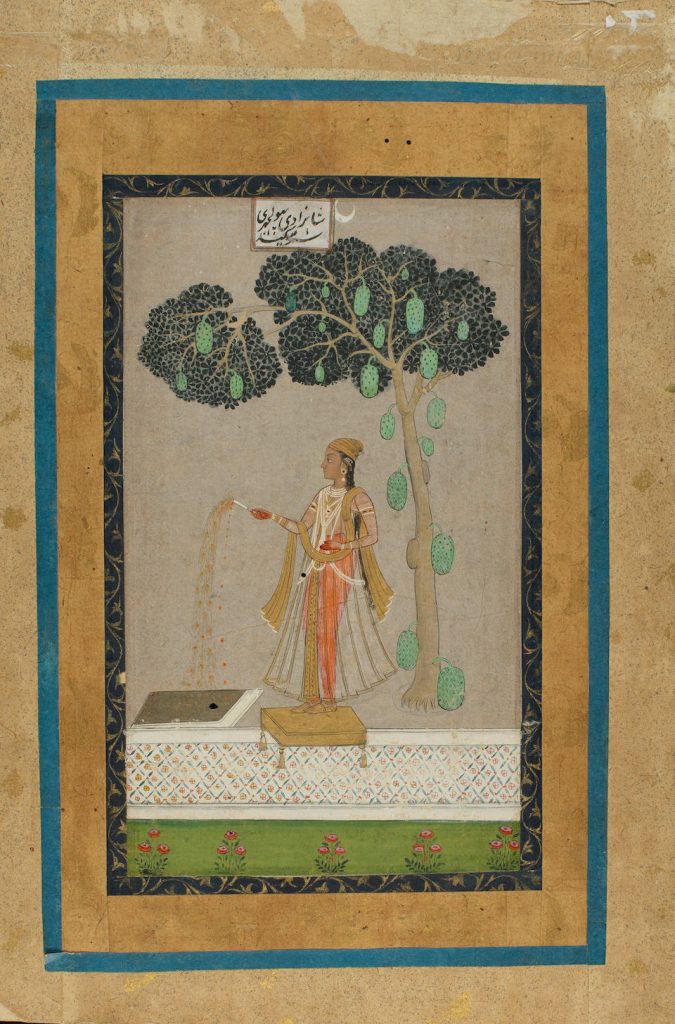

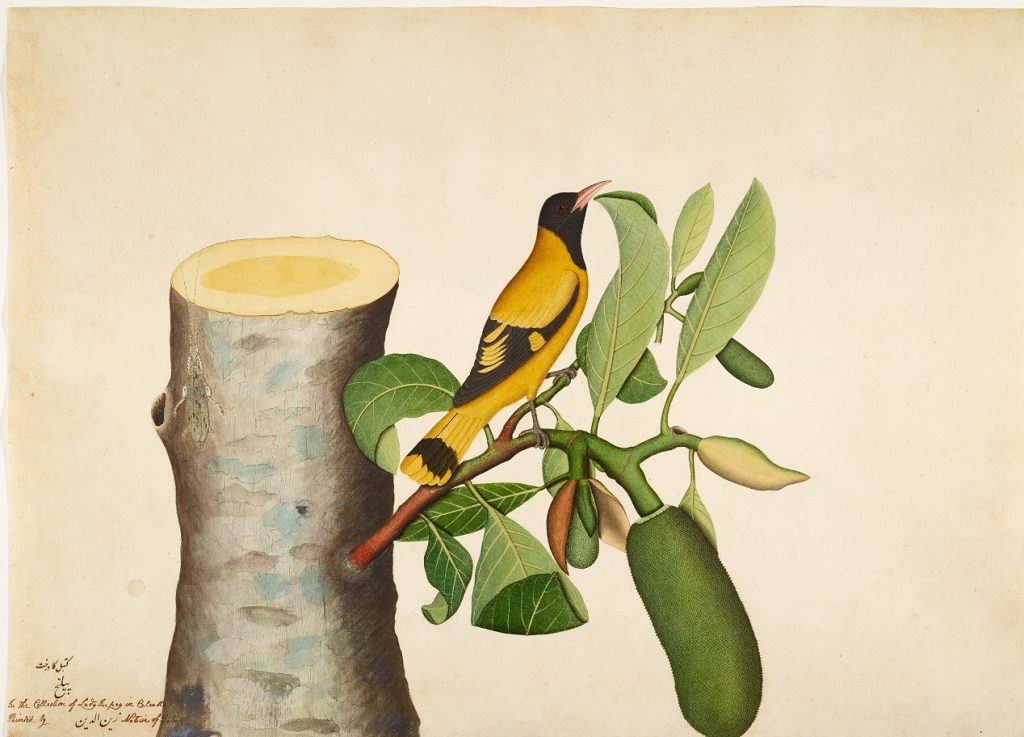

Sajeev’s hypnotic lines are certainly arresting – curiously suggestive yet nonchalant – but this profound punctum[1] introduces an important deliberation on the image he creates. Does his (and by extension, our) intervention produce vigour and movement for an otherwise passive bystander to the process, or is the fruit already animated with a richly-layered history of action and symbolism? I am reminded of a charming folio from 1589 that cuts through this very enquiry Sajeev has introduced. Delicately balancing ink, watercolour, and gold on handmade wasli paper, the royal atelier of the Mughal Emperor Akbar chronicled the subcontinent’s rich culinary heritage in the Baburnama, or the memoirs of Babur. The ornate folio, lettered in the nasta’liq script and abounding with an unparalleled naturalism in colour, style, and technique, captured the gastronomical habits of Genghis Khan’s descendants in regal fashion. In stark contrast with the clinically cold lines of Sajeev, Akbar’s artists visualised a curiosity of the natural world, a marvel of epicurean understanding that provided them with sustenance on and off the battlefield.

What the Baburnama (and other culinary treatises that emerged during this period, like the Supa Shastra from Vijayanagar[2]) did was capture an idiosyncrasy of the land that felt explicit in its excitement. It was celebratory of the soil from which it grew, and tenaciously tender and juicy in the face of scorching elements under the sun. In other words, to see such fruits grow, to live around them, and to eat them in manners hitherto unimagined – was fun. This was a time when every mycelial root spread over the country would gather around with mouth-watering dishes like kothal guti lau pat khar from Assam or panasa pottu kura from Andhra Pradesh (I’m personally more of an appam type of person). No longer mere curiosities, such fruits were venerated, celebrated – regardless of how prickly or unattractive their exterior may be, they were a cause and participant of feasts and celebrations, with ballads sung in their names.

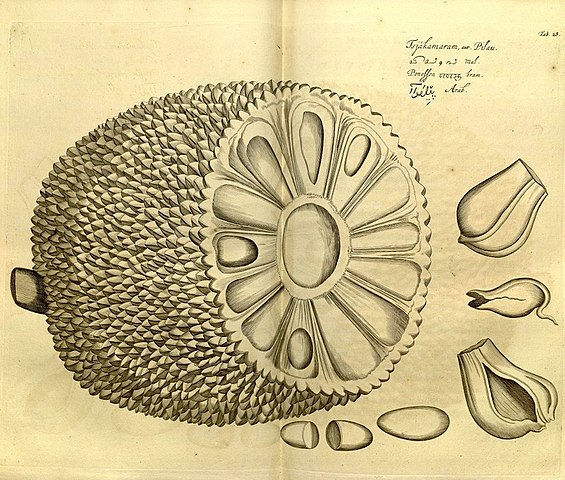

It was only with the arrival of the 17th-century European that our understanding of what we ate changed dramatically. When Dutch settlers captured and studied edible specimens from the Malabar coast for the completion of Hendrik van Rheede’s treatise, Hortus Malabaricus (‘Garden of Malabar’), they produced an academic tome that harnessed such fruits to formulate medicinal treatments exclusively for colonials. The copper plate engravings of the Hortus and the subsequent Company paintings a century later, while perfecting a naturalism of shape and form, considered such foodstuff in a disjointed, aloof, and exoticising manner. Theirs was an academic realism that coldly objectified every minutiae of our reality, recording our gastronomic varieties for the implementation of governance; in precise strokes, modern pigments, and scientific methodology, the art of the subcontinent became a knowledge-building exercise towards the consolidation of Empire. How is it possible that in less than a hundred years, we went from enjoying an abundance of fruity nutrition for everyone, to an imperial system of classification that exercised control over the same?

I apologise if this essay suddenly became a slightly dreary whistle-stop history lesson, but such a provocation is not without merit. When I began ruminating on the visual history of this fruit, I was wholly unprepared for its wondrous and rare – its aja’ib wa-ghara’ib – reality. The totality of my understanding, hitherto this moment, was grossly limited to gorging on spoonfuls of kathal biryani. Therefore, when I saw Sajeev’s works for the first time, I did not simply witness his patient and meditative hand studying a nutritious item of produce – I saw its very potency. It was a potentiality to influence as well as disrupt our understanding of dietary practices; from sensuous and glamorous appreciation by emperors to being tempered by a cold and scientific rationality at the hands of administrators and scholars, I saw a seemingly innocuous and juicy tropical fruit become magical and perplexing across time and space. Sajeev’s canvas was colourless and lacking visual context, and yet rested on a terse history of wonderment, exploration, and conquest.

It is this particularly auratic and characterful history that allows me to wonder just how volatile this fruit is further going to be. There is a large drawing on paper that permits Sajeev to contemplate on an abject reality it would (or possibly, already has) come to inhabit today. His pencil has examined its edible topography, not rushing through a single millimetre of the fruit’s fibrous protrusions, but with an explicit coagulation of conflict and horror. Through a sedate and dignified smear of blood dripping down, the fruit for him is transformed into a sardonic metaphor – a trickster – that is able to define societal attitudes towards culinary agencies. Whether it is contemporary cinema nonchalantly measuring a person’s life against its economic and political value[3], or religious dogma disallowing people from eating it[4], the ‘people’s fruit’ is slowly entering into a disquietude that is deviant and threatening. Perhaps that is why Sajeev’s work seems like it has only been half-bitten; a vessel of anger, filled with blood instead of pulp.

It is entirely possible then, to witness it becoming even more repugnant, an unbearable nausea of banana, pineapple, and rotten onion – or maybe, all we are doing is unfairly blaming a mere jackfruit.

About the Author

Shankar Tripathi is a writer and curator based in New Delhi. Formally trained in art history from Jamia Millia Islamia, Shankar’s graduate thesis questioned the various structures of visuality and countervisuality that informed travel posters and advertising narratives for India during the 1940s-1970s. Focusing on visual and cultural histories, his writings have been featured in spaces like The Punch Magazine, Live Wire, DeCenter Magazine, Indica Today, among others. He was one of the recipients of the Second Young Writers Award in Lens Based Practices (2022) given by Critical Collective and MurthyNAYAK Foundation for writing on Dayanita Singh’s ‘File Room’ series. He currently works with Anant Art Gallery.

Notes

[1]The ‘punctum,’ for Roland Barthes, was that point (literally, a hole) in a photograph or an image that affects the psyche and invokes a response which is more than a casual appreciation – in effect, it is what ‘pricks’ the spectator into appreciating a work beyond its mere formal beauty. See Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), 94-96.

[2]Colleen Taylor Sen, Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India (New Delhi: Speaking Tiger, 2016), 168, 170.

[3]A major plotline in the Netflix film Kathal (dir. Yashowardhan Mishra, 2023) is the disappearance of a lower-caste woman, whose investigation is stymied by the local MLA’s call to divert all security resources in finding his stolen jackfruits.

[4]Strict codes of Jain vegetarianism classify the jackfruit as abhkashya (literally, ‘not worth eating’). Its milky sap is seen as the bloodline of the plant, and by cutting or plucking the fruit, Jains believe that the living organism is killed – motivating a strict abhorrence of the act.