Imagined and Lived Spaces of the Queer Kitchen

AUTHOR

Upasana Das

Rukmini Srinivas writes, in Tiffin: Memories and Recipes of Indian Vegetarian Food: “My mother, whom I lovingly call Amma, spent much time and thought in the preparation of the ‘everyday’ tiffin for me and my seven sisters…the tiffin that Amma made, usually one savoury and one sweet, would be a full meal for me. And every day it was a delicious surprise”. The school or office tiffin, most often cooked by our mothers, has been a social marker of class and caste. An entire (sometimes impromptu) community of people gather around individuals with ‘good’ tiffin, and mothers become these figures who must keep producing whatever the child or their community wants.

The kitchen housed in the space of one’s home, carries a certain patriarchal baggage — this is never transferred on to any public kitchens, where the food being unsuitable to one’s taste is not seen as much of a fault or failing. Experimenting with recipes that have been passed down through generations is seldom looked upon as something ideal, as it would interfere with the taste that a family member recalls from years ago. The patriarchal kitchen is a stifling and bone-numbing space, which privileges a certain Stepford-Wife-like mechanised outlook towards cooking — it is only when women step outside of the patriarchal walls of the home kitchen that they are truly afforded the opportunity to creatively experiment with their own culinary interests.

A year after COVID-19, we were working on ‘The Kitchen Studio’ — a workshop by the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), where we considered the politics of the kitchen, re-imagined spaces, and recalled women’s untold family histories. Meredith E. Abarca writes, in Voices in the Kitchen: Views of Food and the World from Working-Class Mexican and Mexican American Women, about viewing the kitchen as a studio and cooking as artistic expression among women in her community who enjoyed cooking and perceived the activity as empowering. My project partner Jyotsna Ramesh and I then suddenly wondered how queer people had re-imagined kitchens in their own way. What do they dream about when they visualise their ideal cooking space? What kind of community can grow around such spaces? How would labour be thought of in such a context? Anil Pradhan writes that, “in the context of gay food, the process of making food queer and more specifically, the idea of ‘queer kitchens’, play a crucial role in re-presenting, sustaining, and celebrating both queer culinary cultures and queer sexual expression…experimental spaces of culinary cultures have provided consumers, both queer and non-queer, an opportunity to participate in an appreciation of the non-normative through food.” In the 1960s, The Gay Cookbook added playfulness to a range of recipes, which were not presented in bullet points but in rambling paragraphs, bearing the tonal idiosyncrasies of a campy gay man. Written by the chef Lou Rand Hogan, it visualised an alternate space of domesticity and companionship.

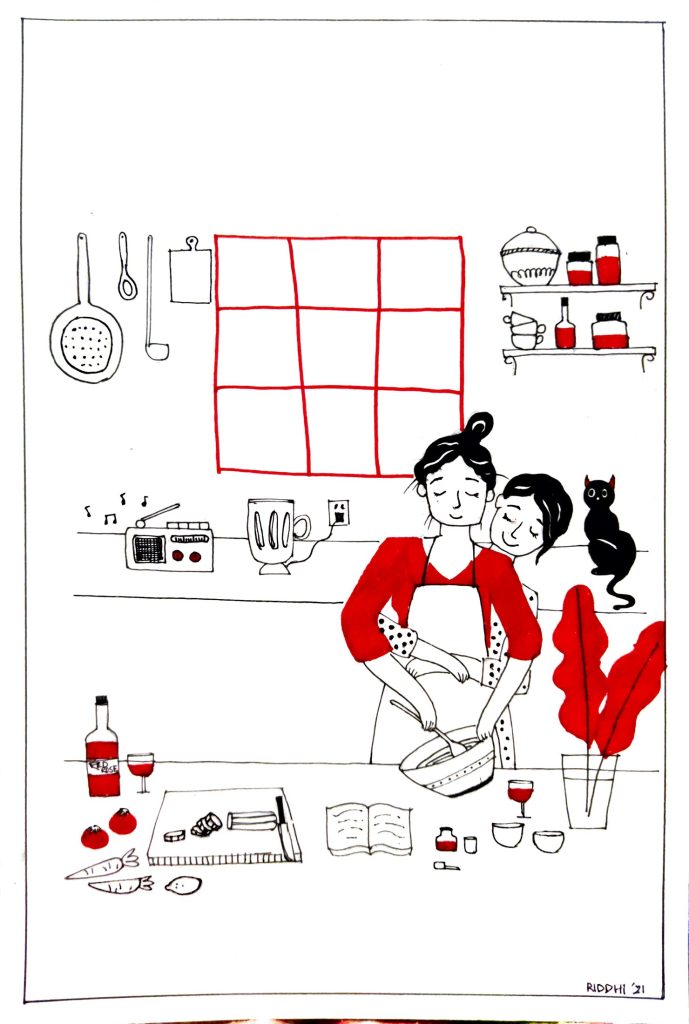

I knew a few queer friends, students, and restaurant owners in my city, Kolkata, and I approached them. The kitchen was a place to hand down tradition, said Riddhi, a friend. Sometimes it also becomes a space for companionship “where the domestic help and ‘bahu’ bond over their miseries and where during a gathering, the women can peacefully resent their families,” she said. For her, the kitchen then became a space that accommodated laughter and experiments. Raj, another friend, mentioned how they laughed with Kakoli maashi, who acknowledges her mistakes around the kitchen without judgement: “She cares even though she does not have to. Sometimes I have a stupidly hard time figuring out how to put the milk back in the fridge where everything is crowded but marvellously organised, and she offers to do it for me.” Riddhi recalled sharing work stories with her grandmother and mother while making dessert together in their home kitchen. They recounted how queer friends shared their cooking duties, not overwhelming each other with kitchen work, and taking pleasure in each other’s company while broiling a mean fish. Riddhi also brought up the tendency of mothers to cook what the men or their children want, instead of what they really want to make, mentioning how her uncle would get irritated if food was not cooked in keeping with his tastes.

Horlicks India recently broadcasted an advertisement featuring a working mother giving away most of a bowl of palak paneer to the entire family. Her children wonder where their mother is going to get calcium and iron from, and they get her a glass of Horlicks, two cups of which are said to provide the required amount of calcium, iron, and other nutrients. “At queer tables and in queer families, I would imagine this unhealthy habit of compromise would cease to exist and that people at the table would come to equally enjoy their meals. There would be an understanding among them about each other’s nutritional needs,” Riddhi said. Care was important in such spaces, since the act of cooking, for Raj, often came from the need to take care of people, be it friends or partners. Although they love eating alone, they would want their queer family to sit together and not merely discuss work but check in with each other at the end of the day: “On some nights, the table will be a floor dinner with pillows littered everywhere.” Their grandmother has a recipe for chilli chicken, which they plan to cook in a gathering. “My didu still has a lot of preconceived notions and is quite bigoted, I won’t lie,” they said. “I like the thought of inviting my queer friends over and making my homophobic and transphobic didu’s chilli chicken for all of us. I don’t know why but something about that feels very funny and powerful.”

Susan Sontag wrote in her diary on the last day of her marriage, that she had eaten a soft-boiled egg, orange juice, and a dish of apple sauce at ten in the morning after her husband Philip left with their son David on a trip. Apple sauce, which is mainly eaten as a side dish, is most likely converted into the main dish here, considering the size of an egg. Putting minimal effort into cooking and spending less time in the kitchen, making do with what is there and finding satisfaction in it, is also a kind of queering, as in a patriarchal family system, this would not work. For Pradipta, another friend, making something as mundane as home-cooked food funky with the use of absurd ingredients that usually don’t go well with each other but somehow do, was a way of parodying the mainstream. Welcoming and sharing food with people who are queer, on a table that doesn’t enforce the etiquettes of dinner at your father’s boss’ house is queer too. The music that is played, the people that come together, the ambience that is created, unhindered by fetters of judgement or roles, is what adds to the queerness of this ritual.

Kyle Fitzpatrick writes: “It is less about what is literally eaten, but it is more than just the presence of queer people at the table. Queer food is the food of a temporary utopia, one where unexpected eating styles and culinary creativity thrive, where things that seem too weird to work, actually work.” Raj mentioned that cooking was something they allowed themselves to be mediocre at and if it did not turn out to be good, it did not harm anybody. The spirit of going-along-with-it is what makes kitchens constructed outside the contours of conventional familial units feel so inclusive. Jennifer E. Crawford in her series ‘My Queer Kitchen’ with Xtra Magazine spills fudge sauce, upsetting the perfect structure, and it is fine, and this can be read alongside the fact that allowing oneself to be messy and make mistakes has no place in the normative kitchen. The Great British Bake-Off contestant Michael Chakraverty talks about his messy kitchen and unconventional cooking practices which has led to disasters like spilling flour. While baking in easy-bake ovens, drag queen Trixie Mattel burns food, creates a mini fire and makes nearly inedible cookies from decades-old dough — it is all fun and in alignment with the spirit of the queer kitchen she has created for herself.

Nandini, who was part of the Amra Odbhut Collective which started Adamant Eve – A Queer Feminist Café, and then the Amra Odbhut Café, resisted cooking until she was twenty, when she entered the kitchen after leaving an abusive situation. Her pleasure in cooking then came from her autonomy in choosing to cook, which was never afforded to her mother. Cooking for her is meditative and her kitchen is private — her relationship with cooking and food has helped her heal. The Amra Odbhut Café had a library with queer and feminist literature and, moreover, held movie screenings, and hosted music and dance-fueled evenings. Like the architecture of kitchens in our houses, the café initially had a small kitchen, which was later extended to accommodate the many people who came to be involved in the process of cooking. At an event where Nandini was overwhelmed, she had many community members come forward of their own volition to help her make coffee and bake cakes.

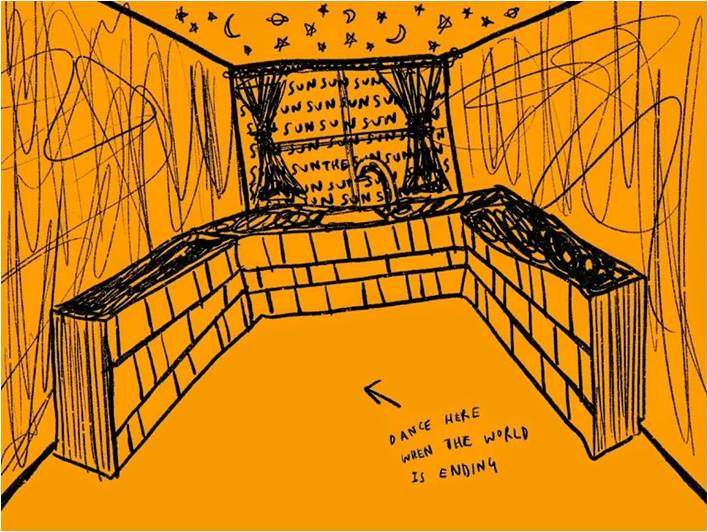

The kitchen is typically a room which is practical, which does not necessarily derive from our personalities in the way that maybe our rooms do. Raj said they had not thought about their kitchen, but they would like a disco light in their space. Although the kitchen in particular does not currently hold much significance for them, they visualise their queer kitchen as full of light, where they can bake cookies with their friend who dances all the while. The freedom and agency in the space is palpable. The kitchen becomes a happy space. It is no longer a space where one is stressed about the food or who will eat it and what they will think, or even just a space only for cooking. In one of our early conversations, Jyotsna had imagined having a kitchen library where she could read. Ways to prevent the cooking oil from affecting the book pages remain to be brainstormed.

“Privileges of class and caste of course continue to exist, as they do in queer spaces too”, Riddhi said, and the queer kitchen does not exist outside of that yet. But a sense of empathy and co-sharing is what they want to cultivate, towards building imaginative and freer futures. It is necessary to keep spaces like these accessible to queer people from all sections of society. For many who do not have many places to fall back on, these are some of the corners which become particularly significant.

REFERENCES & FURTHER READING

- Rukmini Srinivas, and Mohit Suneja. 2015. Tiffin: Memories and Recipes of Indian Vegetarian Food, 3. New Delhi: Rupa Publications.

- Blakemore, Erin. “In The Gay Cookbook, Domestic Bliss was Queer”, JSTOR Daily. January 10, 2021. https://daily.jstor.org/in-the-gay-cookbook-domestic-bliss-was-queer/. Accessed 6th July 2023.

- Abarca, Meredith E. 2006. Voices in the Kitchen. Texas A&M University Press.

- Rand, Lou. 1965. The Gay Cookbook.

- Peach, Lucky. “America, Your Food Is so Gay.” Medium. April 14, 2014. https://medium.com/@luckypeach/america-your-food-is-so-gay-274700774755. Accessed 5th July, 2023.

- Sarkar, Sohel. “Queer Pleasures of the South Asian Kitchen.” Medium. July 7, 2020. https://sarkar-sohel10.medium.com/queer-pleasures-of-the-south-asian-kitchen-ddf7bcf6f786. Accessed 28th June, 2023.

- Klassen Rosenbaum, Stephanie. 2016. “In The Queer Kitchen: ‘Food That Takes Pleasure Seriously'” NPR. July 5, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/07/05/484354089/in-the-queer-kitchen-food-that-takes-pleasure-seriously. Accessed 26th June, 2023.

- Xtramagazine.com. https://xtramagazine.com/series/my-queer-kitchen. Accessed June 15th, 2023.

- Foster, Allison. 2019. “This Queer Kitchen United the Queer Community through Food.” The New School Free Press. October 5, 2019. https://www.newschoolfreepress.com/2019/10/04/this-queer-kitchen-unites-the-queer-community-through-food/. Accessed 1st July, 2023.

- Bridsall, John. 2017. “How to Start a Queer Kitchen Revolution.” Vice. December 19, 2017. https://www.vice.com/en/article/xw4xyw/how-to-start-a-queer-kitchen-revolution. Accessed 1st July, 2023.

- Fitzpatrick, Kyle. 2018. “Queer Food is Hiding in Plain Sight.” Eater. June 28, 2018. https://www.eater.com/2018/6/28/17508420/what-is-queer-food. Accessed 1st July, 2023.

- Rasmussen, Crystal, and Tom Rasmussen. 2020. Diary of a Drag Queen. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Hart, Hannah. 2014. My Drunk Kitchen: A Guide to Eating, Drinking and Going with Your Gut. New York, NY: It Books.

- Pradhan, Anil. “Too Gay an Oreo!: The Cultural Connotations of Queer(ing) Food.” 2020. Café Dissensus. January 28, 2020. https://cafedissensus.com/2020/01/28/too-gay-an-oreo-the-cultural-connotations-of-queering-food/.

- Sontag, Susan, and David Rieff. 2009. Reborn: Early Diaries, 1947-1963, 149. London: Hamish Hamilton.

About the Author

Upasana Das is a writer and researcher currently working with DAG Museums. Upasana has been part of creative-research programs at the Foundation of Indian Contemporary Art (FICA), Asia Art Archive (AAA), Mumbai Academy of Moving Images (MAMI), Serendipity Arts Foundation (SAF) and Film Heritage Foundation. They were an Artist-in-Residence for Pickle Factory’s “Home for Dance” residency in 2021. They are also an Archivist at The 1947 Partition Archive. Upasana has exhibited their work at The Irregular Arts Fair 2020, Paprika Festival (Canada) 2020 and are part of the Beyond Borders programme by Young People’s Theatre (Canada).