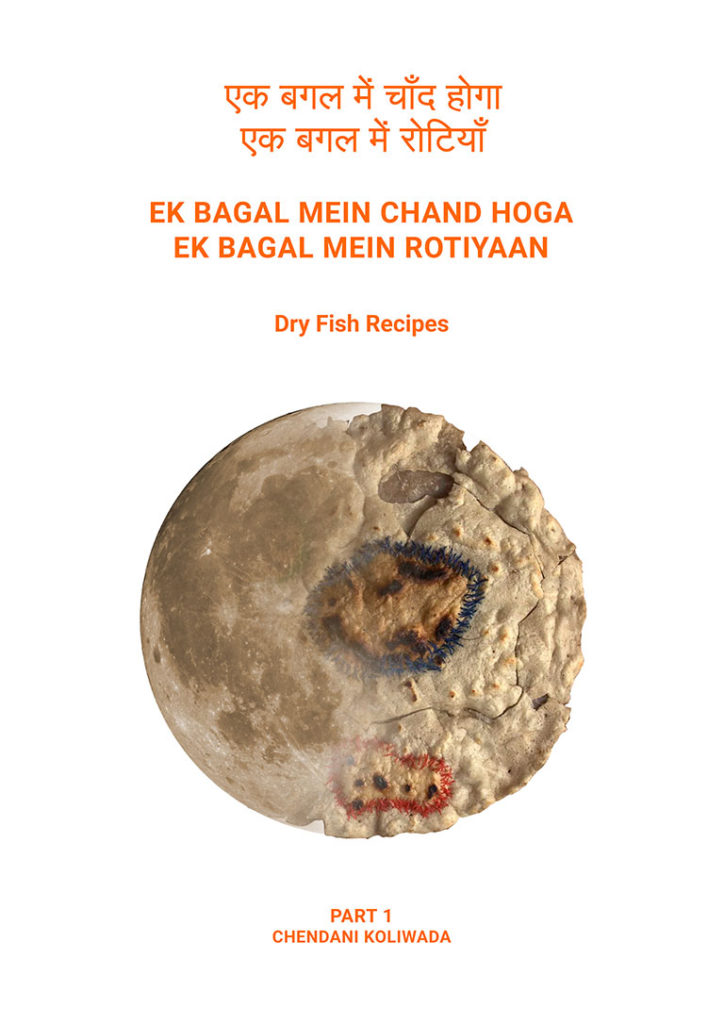

एक बगल में चॉंद होगा एक बगल में रोटियाँ

On One Side Lies The Moon, On The Other Lies The Bread

AUTHOR

Parag Kamal Kashinath Tandel

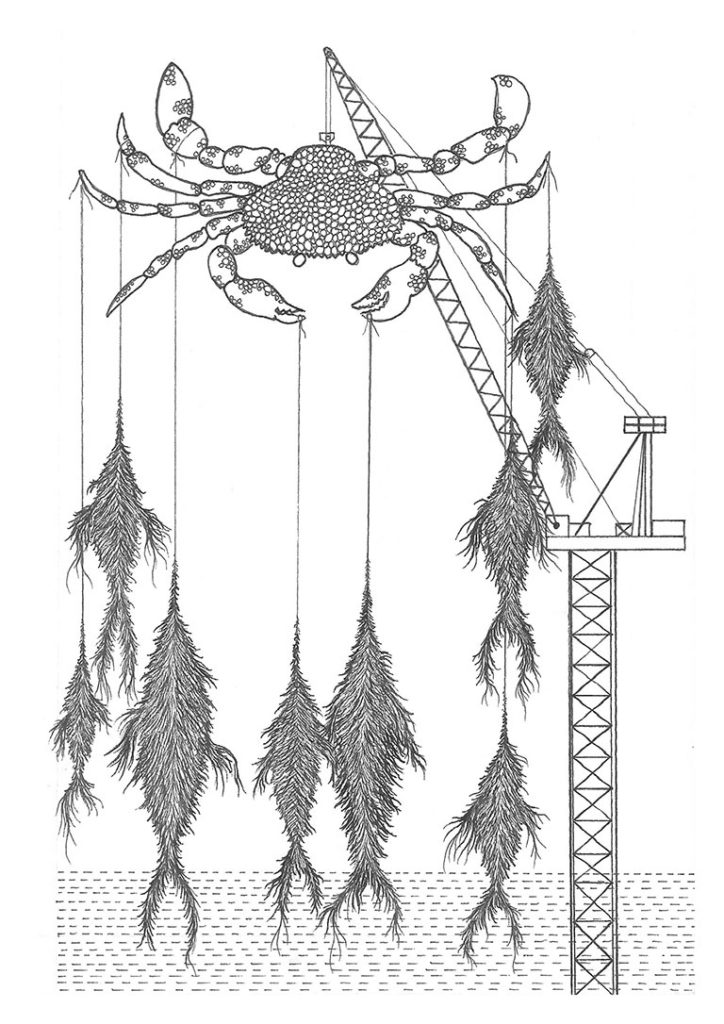

The title of this essay is a lyric that looks closely at the two complexions of the moon—as a star, and a metaphor for bread. It relates to the Son Koli community, comprised of fishermen in Mumbai, and their dependence on the moon. The functionalities, literal and allegorical significances associated with the moon since ancient times as well as today are pertinent to us, when many of Mumbai’s local, indigenous vocations and traditions are on the brink of extinction. Since the past decade and a half, there has been a shift of occupation in the Koliwadas (fishing villages) in and around Mumbai. Fisherwomen have started selling rice rotis to restaurants in Mumbai. Today, you will come across five to fifteen women in each Koliwada who produce between two hundred to four hundred handmade rotis every day. This is a direct consequence of the deserted river estuary and ocean, as well as rapid urbanisation and industrialisation which has polluted the water bodies of Mumbai, and ruined the naturally thriving environment of river estuaries and mangrove forests, depleting many species of aquatic life. This essay is part of a larger project that employs a socially-engaged performative research methodology to collect evidence in the form of intangible and tangible narratives related to the ecology of indigenous people. It is a long-term engagement to create handmade manuscripts in order to archive the shifts in the lives of communities living on the peripheries of the ocean. Each manuscript will be published as a work of art upon the culmination of the project.

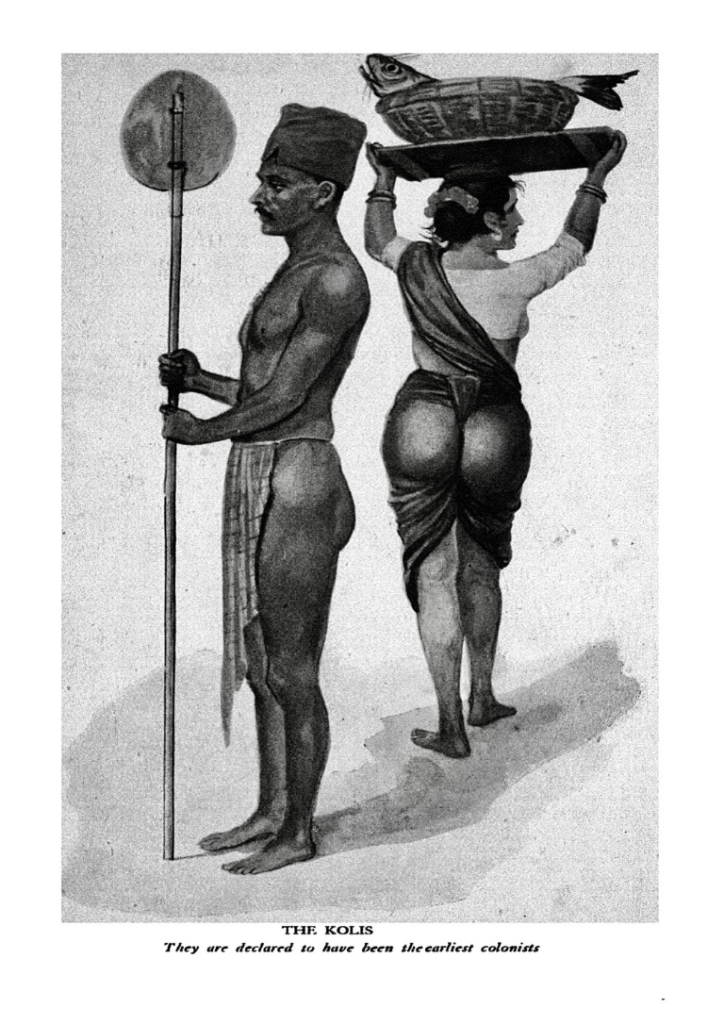

Son Koli tribes are indigenous inhabitants of Greater Mumbai, Navi Mumbai, and Thane which together form a megalopolis. Their genealogies on the seven islands can be traced back to the Stone Age. There are more than 275 Koliwadas in and around Mumbai, and each Koliwada has its own social and cultural practices. Although the city has grown around them, these isolated villages have retained their own identities in Mumbai. They are self-sufficient, situated on self-sustaining lands, and not dependent on the city’s infrastructures. Koliwadas have their rich natural resources and cultural existence. But in recent times, these sea-facing villages are being eyed by developers as prime properties and as the land of opportunity. Can one imagine the fisherfolk community without an oceanfront?

Amidst the kaleidoscopic confusion that characterises the population of Bombay, Son Kolis stand out distinctly, retaining the essence of their traditional culture even today. A number of books, travelogues, documents, and articles have referred to the ‘Koli’ tribe. One common factor underlying all these references is that the Kolis are always associated with the fishermen of Bombay – “older than the coconut palm, older than the Bhandari palm tapper are the Koli fishing folk of Bombay among whom, if, in any one tribe, one must seek for the blood of the men of the Stone Age.”[1] Their degree of aloofness from the rest of the urban population and the slight amalgamation of the new with the old has presented a culture that is both elusive as well as intriguing. This elusive quality proved too attractive and led me to study their way of life, the extent to which they have been urbanised, as well as their ancestry. The questions addressed in this research project are: Are they as traditional as they look? Are they truly the original settlers of Bombay and the Konkan Coast as most texts describe them to be? Are they synonymous with the Mahadev Kolis? When did they cease being a tribe and why?

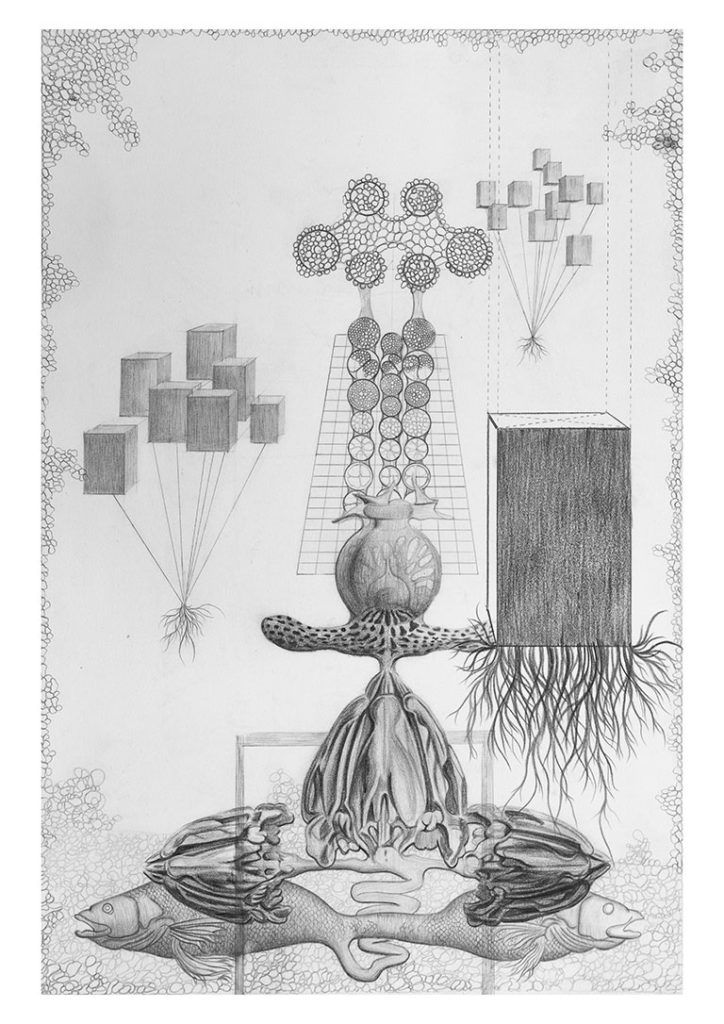

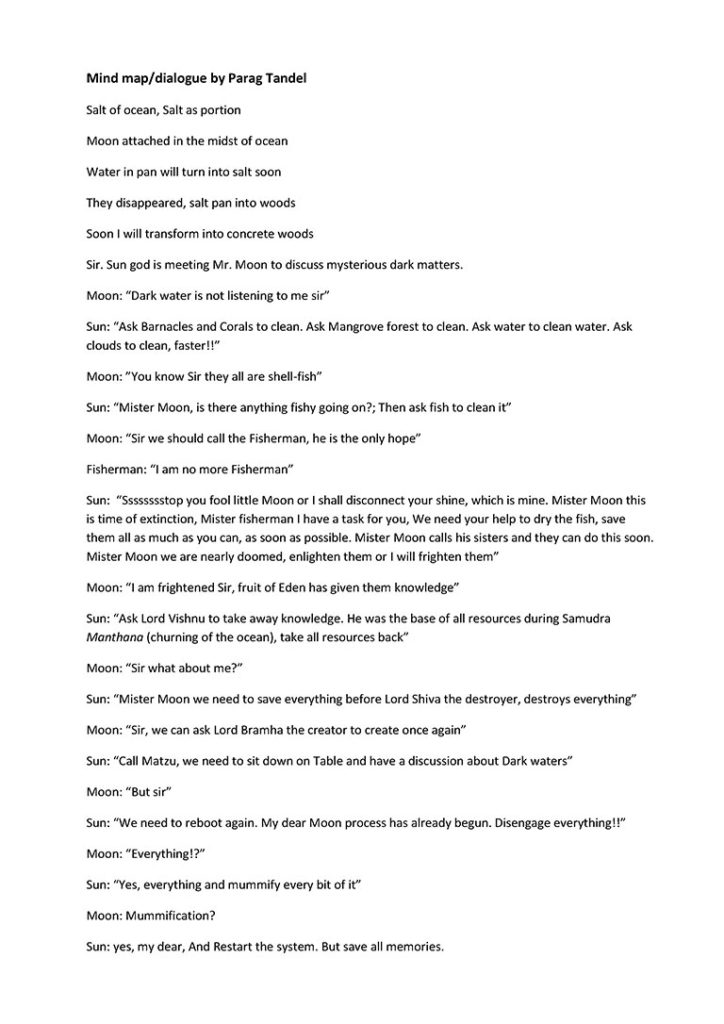

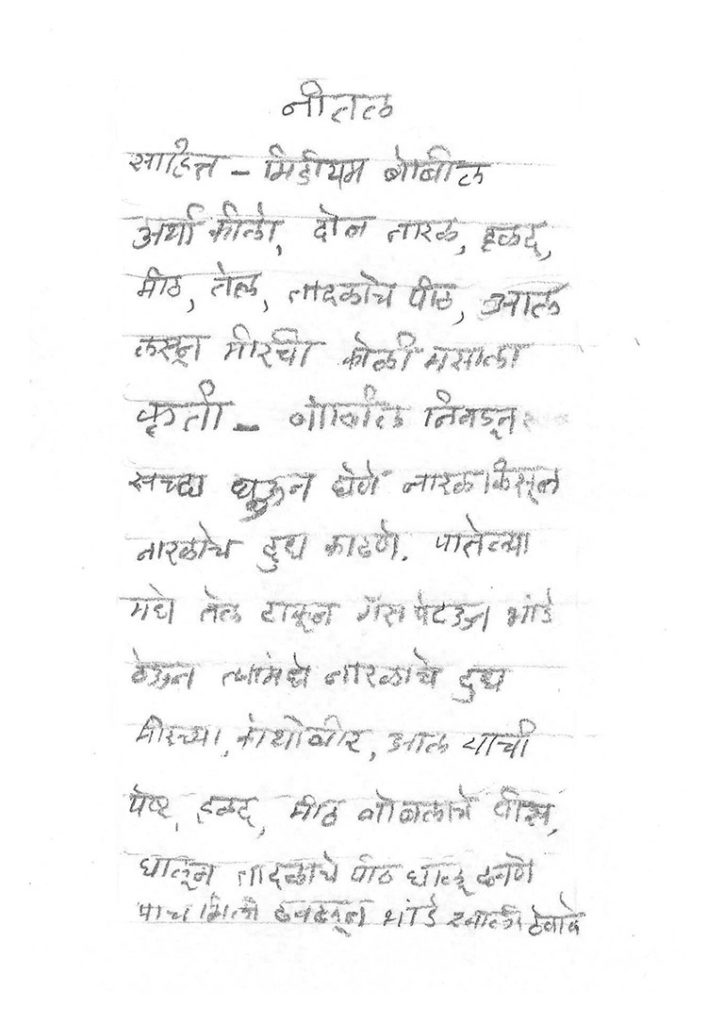

Out of the 275 villages in the megalopolis, my case study started with twelve Koli women from Chendani Koliwada in Thane (a central suburb of Mumbai). Chendani Koliwada is an ancient port which lost its traditional livelihood and local language a decade ago making it crucial to study the ecology of this village. It began with a contest of making a roti with the largest diameter and a revival of old, lost dried fish recipes. Handwritten recipes and narratives were recorded in a manuscript by these women from Koliwada. Being a visual artist, I mapped their oral narratives in the form of diagrams for each recipe. The women also treasured a few found materials from a nearby river estuary as evidence of the dead water bodies. The research-based performance culminated in an exhibition of found objects and various types of dried fish, used in the recipes, which were mummified by the women, symbolising the preserving of the evidence of loss.

The Son Koli is a matriarchal community. For the past few centuries, till the mid-twentieth century, they were traders whose major trade routes went through the ports of East Africa, Persian Gulf, Gulf of Oman, Gulf of Aden, Arabistan, Rangoon/Yangon and Sri Lanka. In those days, fishing was not such an intrinsic part of their lives, but rather a form of art or tradition. The men used to travel for six to seven months of the year, so the women were solely responsible for overseeing family matters. I see this present tradition of roti production as a stand taken by the women of the Son Kolis to be responsible for the sustenance of their families. Koli women take the lead in the management of domestic affairs, the entertainment of guests, the control of the family purse, and planning and participation in festive occasions.[2]

Roti is a basic staple food that is a part of the daily breakfast in the community and wider region, accompanied by any dry fish dish. In the afternoon, Kolis have rice and fresh fish ambot (curry), as the women are busy segregating and drying the fish that they must cook instantly. For dinner, they eat roti made of rice flour and ambot again. Rice has been a common staple food for the past one and a half centuries. Earlier, roti was made of ragi, sorghum, and Patni rice. Conducting a contest was crucial, as selling rotis for a livelihood is seen as a very inferior job in the community as compared to fishing. The contest strengthened the morale of the women and moulded the minds of the community, much like what public sculpture is about – the ‘shaping of minds’.

It is an old ritual to collect and preserve dry fish for food security during pre-monsoon as fishing activities are halted in the monsoons because the seas are stormy and the fish need to mate to replenish their population. The Kolis believe that dry fish tastes best during this time. Dried fish recipes are also cooked on occasions like death ceremonies as a symbol to ensure a secure food repository in the afterlife. Preparations using these recipes cannot be found in restaurants; I still haven’t found any restaurant which exclusively serves dried fish, surely because of its overpowering odour.

Sculptural outcome as evidence - Mummified fish

Later, I requested them to bring similar fresh raw fish which was cooked for the dry fish contest. Together we applied a coating of natural neem resin and lacquer on the fish which was dried and then wrapped in linen like in the Egyptian mummification process. The Egyptian mummification process was influenced by the ancient fish-drying technique that involved the use of salts to remove moisture, which is still used in the Kippered fish technique. Mummification has evolved since its invention and has been applied for many different purposes.

The Blue Revolution is also known as ‘Neel Karanti’ and its goal was to attain economic abundance in the country and encourage the fisherfolks and fish farmers to participate and contribute towards food security in India. It was seen as an asset to generate revenue and create employment and livelihoods. Deep-sea fishing was introduced and highly recommended to artisanal fishing communities. The Blue Revolution introduced bottom trawling and midwater trawling. Bottom trawling is highly disadvantageous because the trawl is dragged across the seafloor, scooping up everything in its path, including non-edible marine species. This whole catch is then segregated into edible and non-edible/by-catch stock. The non-edible catch is then dried and crushed into a powder and supplied to animal husbandry, poultry, and fish farming industries. These farmed animals, poultry, and fish are grown in an unnatural, controlled timespan and environment. They are injected with steroid hormone implants used for growth, and to grow fast they need nutrition which is provided in the form of dry fish powder and other artificial supplements.

In 1960, the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation was founded and many heavy industries, chemical plants, and nuclear plants were set up in and around Mumbai. It seemed manageable for industries to discharge effluents into the estuaries of Mumbai back then. But they never thought of its impact on the future, which would result in deserted water bodies. These people have been trying to restore the fishing zones since the last few years, but their greatest setback has been the impact of the city’s untreated waste. The problem with waste discharged from human activity is that we don’t view it as an asset. We need to see it as an asset and develop a new culture of recycling and upcycling.

Architects, masterplan makers who develop vertical cities that include gardens, playgrounds, swimming pools, sewage pipelines, and other amenities, need to organise waste management and its treatment more efficiently. Oceans, rivers, and other natural water bodies are not dumping grounds for human waste.

Developers and architects must consider indigenous populations before planning new smart cities. The estuarial oceanfront villages are not slums but residential spaces of these communities that have been thriving since ancient times. These spaces have been designed keeping the social aspect in mind; the Koliwadas bring together minds and develop solidarity more organically as compared to vertical cities. There is an honour in this expanse which is lacking in the megalopolis. The knowledge system and cognitive skills of these indigenous communities are inseparable from their lands. Hence, it is important to understand that pollution not only leads to the loss of livelihood but also a slow degradation of their morals and beliefs of ‘Naturalism’ which is pertinent to their existence.

Notes

1 The Bombay of the olden day has been described as “the desolate islet of the Bombay Koli fishermen” (Da Cunha, 1900:5), (Gaz.Bom.City & Ils, II ;2)

2 Strip, Oliva; Strip, Percival. The Peoples of Bombay.Thacker. 1944. P 21.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Parag Kamal Kashinath Tandel is a visual artist and sonic autoethnographer of the Son Kolis (fisherfolk) and indigenous people of Mumbai. He is the co-founder of Tandel Fund of Archives, a socially engaged ethnographic archive and pop-up museum of the Koli community. He lives and works in Thane, Maharashtra.