Pictorial Art in Bengal in the Age of Photo - Mechanical Reproduction

Author

Shaon Basu

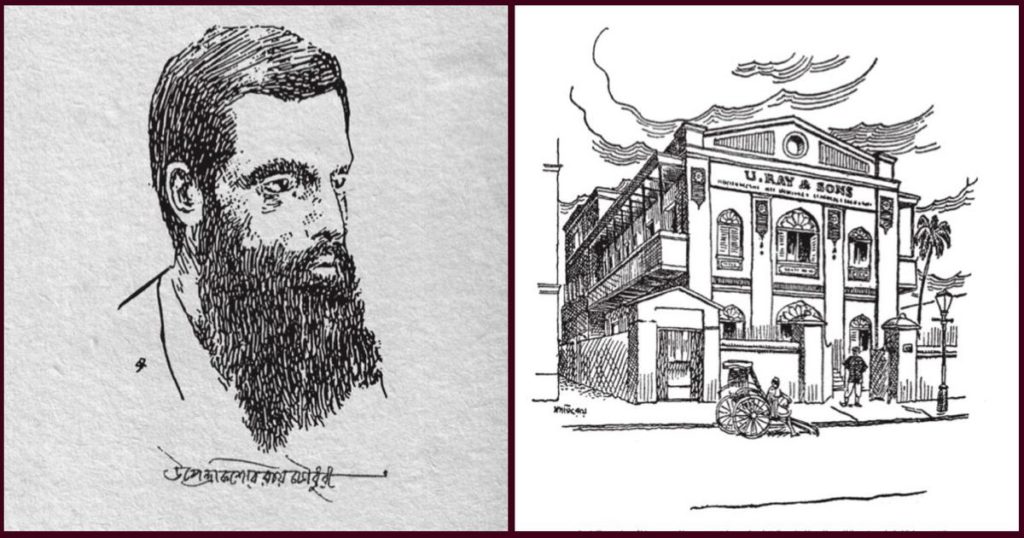

Upendrakishore Ray and the beginning of ‘half - tone’ image

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, Kolkata (then Calcutta) was a melting pot for artistic activities like picture-printing, fine arts and ‘Bazaar’ art, and studio-based photographic practices. Upendrakishore Ray (1863-1915) belonged to the first generation of practitioners of photography in Kolkata. His scientific flair mixed with the artistic passion led him to set up a photography business, specialising in bromide enlargements. But Upendrakishore’s life cannot be fitted into the prism of Bengali ‘bhadralok’ mentality (a mentality to be seen in a typically upper-caste and class urban intellectual of late nineteenth century Bengal upholding the Western values of ‘Enlightenment’). Before getting into the photography business, he spent his early career repairing violins in Dwarkin’s, one of the earliest music shops of Kolkata. As filmmaker Satyajit Ray, Upendrakishore’s grandson, succinctly put it: ‘Upendrakishore embodied a remarkable fusion of science and art, of East and West. He played the pakhawaj as well as the violin, conducted original research in printing technology whilst composing Brahmo devotional hymns, studied the heavens with a telescope from the roof of his house, retold the epics and rural tales in inimitably lucid prose for children, and also used oil and watercolour, or pen and ink, to produce pictures that were consummately Western in style.’1 Soon after reading the little that was available on the complex ‘half-tone’ technology of photomechanical process which does not compromise on the tonal gradation of the original photographic image, and also reproduces it for a fraction of the price of a wood-engraving, Upendrakishore ordered the requisite printing equipment from the Penrose Company in England and embarked upon learning this novel technology. It is ironic ‒ however, ‘not inappropriate’, as historian Chandak Sengoopta notes ‒ to picture the arrival of the equipment ‘in huge crates carried by bullock carts’ as the ‘symbol of colonial modernity.’2

Thus began Upendrakishore’s journey in mastering this new craft, heedless of time, expense, and even health, as his son Sukumar Ray has noted.3 Rabindranath commended highly of ‘the mental strength and effort required to master and then to improve this new craft in India, without any kind of assistance or advice.’4 Faced with a limitation of space at his Cornwallis Road house, he moved out in 1895 to set up a studio first in Sibnarayan Das Lane, and finally, in a larger house in Sukea Street. This house at 100, Garpar Road would be the office of the famous printing press ‘U. Ray and Sons’ for years to come, and would be known as Satyajit Ray’s birthplace in 1921, as chronicled in the memoir on his childhood titled Jokhon Chhoto Chhilam (When I was small).

Upendrakishore was already a writer in many Bengali periodicals dedicated for children. Sukumar Ray notes that in 1897, following profound disappointment with the poor quality of the woodcut illustrations made by him in the pages of his first publication Chheleder Ramayan, (curiously, although chheleder translates to ‘boys’, it was a gender-neutral term for ‘children’ at that time), his focus completely shifted to perfecting half-tone printing. In July of the same year, we have evidence of him claiming that he is now able to produce half-tone blocks ‘as very few persons in the world have hitherto produced’ and the blocks could produce patterns that were ‘simply innumerable’ following a rigorous scientific research that earned Upendrakishore international acclaim.5

The Age of Illustration

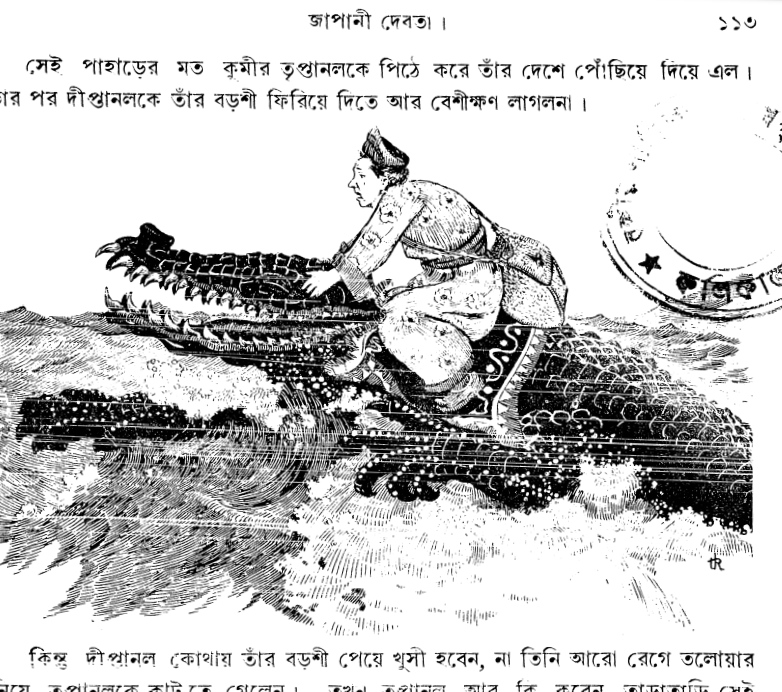

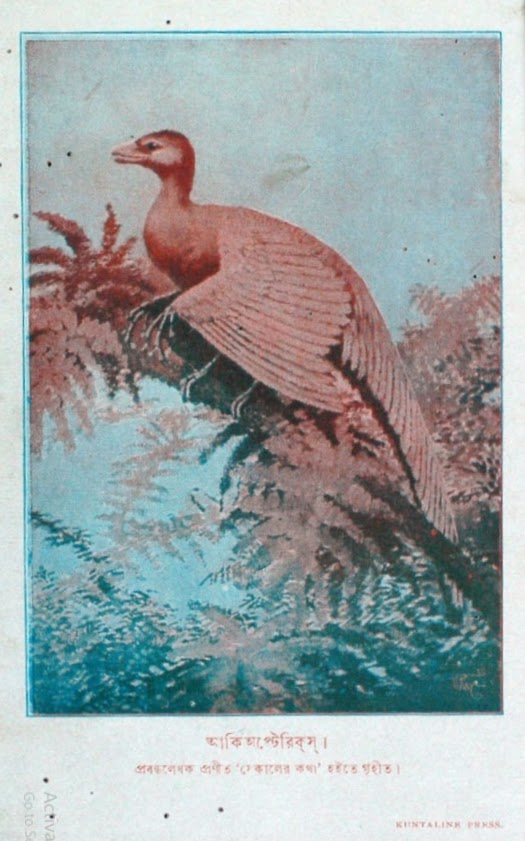

In 1910, from his new workshop in U. Ray and Sons emerged Tuntunir Boi (“The book of hummingbirds”) featuring illustrations of unprecedented quality. In 1913, Upendrakishore would launch his own children’s magazine, Sandesh, from the same press. But as early as 1903, in his second publication Sekaler Kathha (an illustrated book for children about prehistoric animals) he had a series of black-and-white illustrations of dinosaurs, and especially a multi-coloured frontispiece depicting ‘Archaeopteryx’ that won accolades from Thomas Holland of Geological Survey of India, Alexander Pedler of Bengal Government’s Public Instruction, and even the famous artist Ravi Verma for its scientific verity and aesthetic quality.

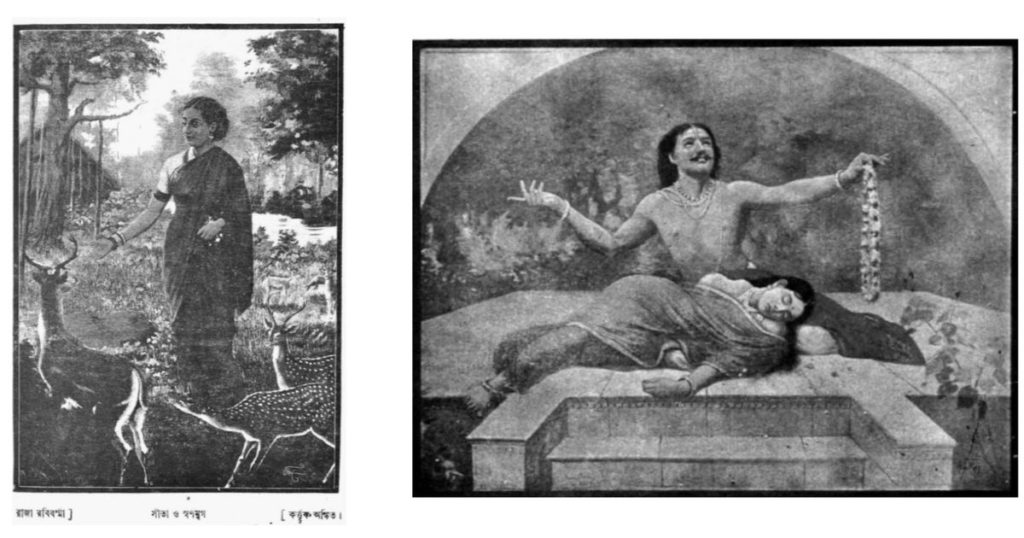

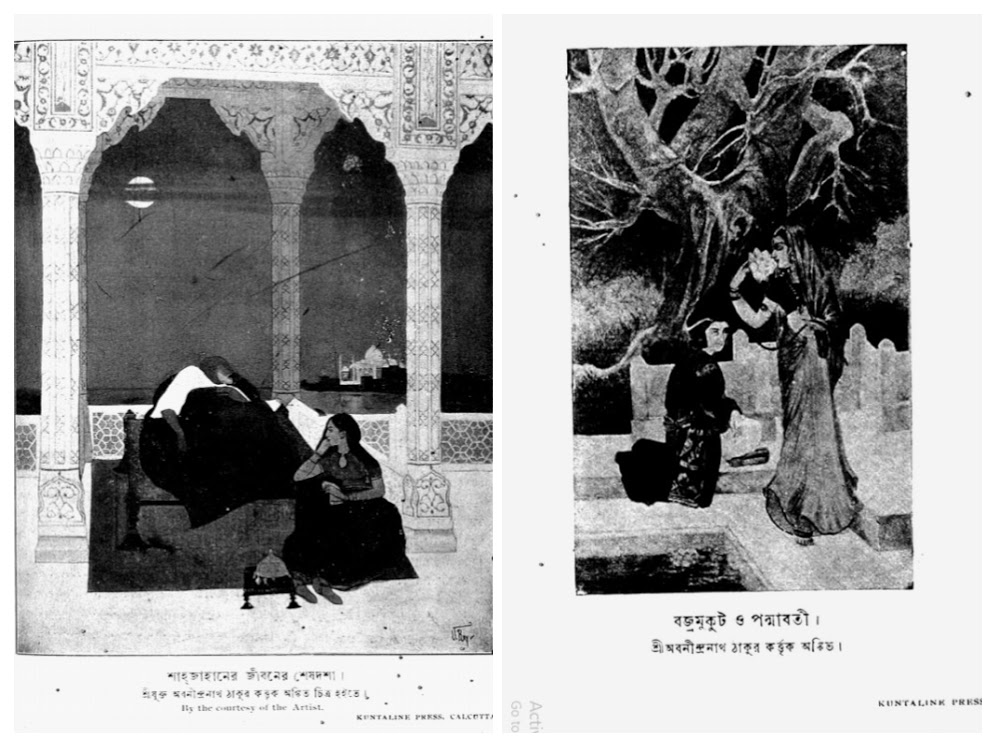

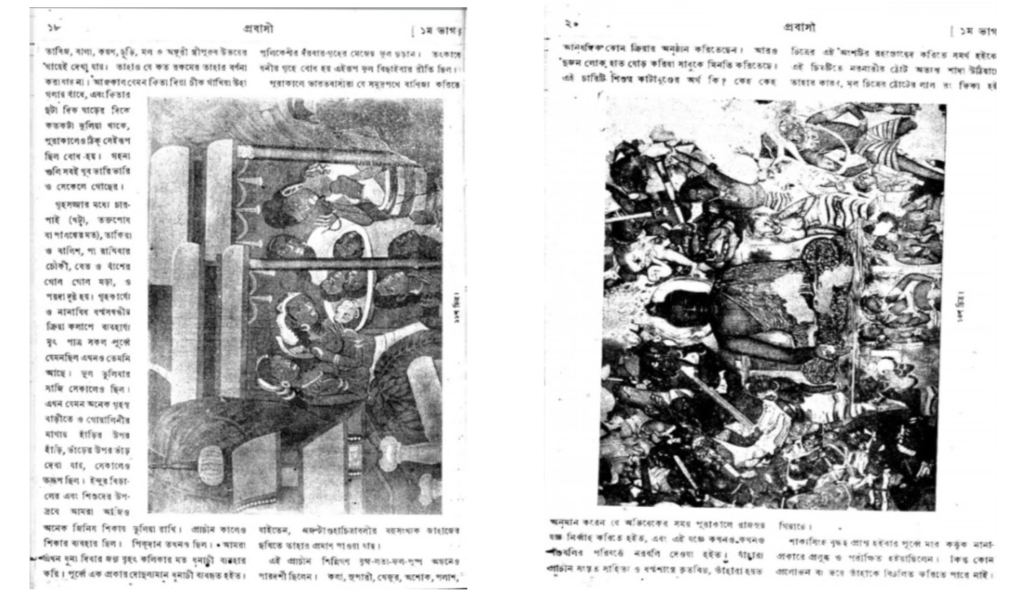

Ravi Verma’s praise for Upendrakishore’s works is not surprising. U. Ray and Sons were preparing brilliant half-tone blocks of several of Verma’s paintings since the inception of Probashi in 1901; and in 1903, Probashi carried out a three-coloured reproduction of Ravi Verma’s painting Aja-Bilas. It was to be the first multi-coloured reproduction of Indian painting in any Indian publication. Ramananda Chatterjee used to reproduce artworks from famous art galleries, bringing home famous arts of the Western world for his readers in Probashi. However, an ardent nationalist, Chatterjee soon realised that universal language of art can be used to forge a national unity, and noting that Indians were scandalously ignorant about the cultural life of the regions other than theirs, filled the pages of Probashi (Bengali-language; circa 1901) with pictures of art and heritage sites building a repository of art which could allude to a possible pan-Indianism. Chatterjee’s first magazine Pradip was so full of pictures that Rabindranath Tagore warned him to not spend so lavishly on illustrations lest he go bankrupt.6 But one could sense a shift in Chatterjee’s conception of ‘national art’ during the Swadeshi movement in Bengal (1903-1908).

Chatterjee earned accolades from the British for his keen eye on illustrations and design alongside its rich textual content in his English-language magazine Modern Review (circa 1908). British magazine Light’s review, after seeing the first two issues of Modern Review, was celebratory: ‘We are certainly surprised to see them. We have nothing more important-looking, more enterprising and more serious.’ Bande Mataram edited by Aurobindo Ghosh noted, ‘Its wealth of illustration is really wonderful and it spends it for the benefit of the readers with a lavish profusion which is really oriental … its wealth of illustrations pales before its wealth of articles.’ Chatterjee, with the help of state-of-the-art printing technology and also a sharp understanding of cultural politics of his time, launched as an editor a programme for aesthetic education for the masses of India.

‘It is because of Ramananda baboo’, Abanindranath Tagore once said, ‘that art has now reached the households … his diligent enterprising created the demand for pictures in public [sic]’. Tagore continued, ‘This wide campaigning of the Indian art was not possible even by the art society [sic]. We tried. It didn’t happen. … We would have left painting, but he did everything … to deliver pictures of arts of our country and abroad in each of the poor households.’7 Chatterjee also initiated an important practice of paying a sum of money to the artists and the writers as ‘honorarium’ for contributing to his magazines. This was unprecedented in this country. Note, however, that what started as an effort to bring together arts of all kinds became a mouthpiece for the Bengal School of Art, a highly mannerist art claiming to be truly Indian, following the Swadeshi uprising in Bengal.

On one hand, Chatterjee’s intellectual project of promoting ‘art’; and on the other hand, Upendrakishore’s vision for children’s education, sugar-coated in nirdosh amod (harmless entertainment) broadly characterises attitudes towards pictorial art in the following decades in Bengal. Upendrakishore’s open debate against the spiritual, non-naturalistic art of the ‘Bengal school’; his fidelity to the ‘criterion set by Western Academic norms’, assimilating ‘photographic, realistic values’ in his work made him an arch-European in the matters of pictorial art. In the West, half-tone was popularised as ‘the portraits of nobodies’; capturing every sphere of urban, popular life and earning the status of ‘the mass image’. In India, as we can see, it enjoyed a different life ‒ it was a vehicle for setting new (and often ‘high’) trends in visual culture ‒ literally adding many shades to the country’s diverse history of print culture.

Notes on Images

The first image is taken from the edited volume of Satyajit Ray’s writings, Sera Satyajit, published in 1991 by Ananda Publishers, Kolkata. Other images are taken from the CrossAsia repository of Bengali periodicals courtesy of Hiteshranjan Sanyal Memorial Archive in collaboration with Heidelberg University. They are accessible from the following link: https://www.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/Englisch/fachinfo/suedasien/zeitschriften/bengali/overview.html

Notes

1 Satyajit Ray, ‘Bhumika’, in Sukumar Sahityasamagra Volume 1, eds. S Ray and P Basu (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, 1989), 1.

2 Chandak Sengoopta The Rays Before Satyajit: Creativity and Modernity in Colonial India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2016), 133.

3 Sukumar Ray, ‘Upendrakishore Ray’ [1916], in Sukumar Sahityasamagra Volume 3, eds. S Ray and P Basu (Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, 1989), 79.

4 Rabindranath Tagore, ‘Samayik Sahitya’, Bharati (22): 1898, 764.

5 Siddhartha Ghosh, ‘Abol Tabol: The Making of a Book’, in Print Areas: Book History in India, eds. Abhijit Gupta and Swapan Chakravorty (New Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004), 243-44.

6 Rabindranath Tagore, ‘Samayik Sahitya’, 766.

7 Santa Devi, Bharat-Muktisadhak Ramananda Chattopadhyaya O Ordhasatabdir Bangla (Kolkata: Dey’s Publishing, 2005), 152. Text translated from Bengali to English by the author.

About the Author

Shaon Basu is an artist and independent researcher currently based in Kolkata. He recently completed his master’s from the Department of Art History and Aesthetics, MSU, Baroda. He wrote his master’s dissertation on the shifting trends in picture-printing in colonial Bengal.