The Rambles of Fatigued Listening in 5¼ Movements

AUTHOR

Suvani Suri

Movement 1: The Burrow of Unsound

The air smells pungent and arid. Fatigue traverses and slowly fills up the site of what once was a burrow, now turned outside-in. Heavy and dazed eyelids gaze at the last remaining parts of the immaculately constructed stone walls, hearkening back to that moment when a faint whistle first slithered into the labyrinthine passages of the burrow. The crumbling walls are starting to heave and sigh, occasional rumbles giving way to a steadier, humid rhythm spreading all the way through the cracks of the floor into the pulsating pores of the skin.

The story of Kafka’s Burrow1 is one that brought me to uncanny sounding and resounding. It is a tale of anxious listening. A nameless and undefined creature inhabits the story. It is most likely a mole or a badger, going by the signs that lie scantily strewn across the volume of a convoluted underground fortress. A register of hyper-listening is invoked by a piercing sound that hears the mole, even before it feeds into the signal at the edge of sleep and wakefulness. Like an earworm, the “inaudible whistling”2 wriggles its way from the depths of the mole’s interiorities all the way into its aural faculties. From an inside to an outside, from refuge to peril, it spirals all the way through the wormhole into the extimate. Driven to the edge by the task of locating the source of this acousmatic sound, the mole steadily enters into a state of neurotic surveillance3, a sousveillance. The whistle is writing the mole as it keeps looping into a feedback of its own making, eventually demolishing the burrow. In a bid to excavate its way out of the clutches of the disconcerting unsound, a circuitous route is taken by the mole towards what seems at first like an urgent escape but then it homes in on the task of identifying the bug. Scuttering up to the thresholds of an erstwhile burrow, now dizzy with exhaustion and yet not being able to metabolise the inexhaustible ringing, this marks the first retreat. A retreat into the orbit of the dislocated voice overflowing with weird echoes that brush against the undulating surfaces of a future anterior and bounce back into the unhomely present.

Movement 2: Anxious Listening

There’s a peculiar anxiety that I experienced when encountering the archive of the Linguistic Survey of India (LSI)4. An acute sensation that I often relate to a contingent tryst with spaces, situations, scenes and worlds that feel oddly familiar, while being complete strangers. The split felt within a fleeting moment, when strangeness exudes an uncanny intimacy and pulls one into the necessity of tuning into frequencies other than of one’s own, an inside-out.

The LSI was an ambitious colonial project, headed by George A. Grierson and conceived with an administratorial intent. It produced a massive collection of voices, sounds, and utterances in various languages and dialects captured from all across the Indian subcontinent in the years from 1914 to 1928. It bloated and bulged in all directions to contain abundant histories in the form of songs, ballads, stories, and polyvocalities. In my second attempt to retreat from the burrow, I fell through the cracks and cavities of the phonographic recordings.

All in all, the LSI audio archive is filled to the brim with the weight of listening. It interlocks with the anxieties of the monarch in Italo Calvino’s A King Listens5, who is so consumed with the paranoia of revolt by his subjects that he wants to (over)hear every single acoustic signal in the burrow of his castle. One day, his excessive listening is interrupted by a singing voice. In a similar manner, Griersom dreamt of the expansion of the empire, fuelled by the hunger for ears that could hear, interpret and anticipate every language that was ever spoken in the subcontinent. The coloniser’s body is covered with sinuous horns that perform acts of auditory espionage and extraction. An excess of hearing that bores deep into the systematised and structural languages of caste, class, race, and borders, to extract, swallow, fortify and accumulate. A hungry listening.6

Movement 3: Hypnagogia

A curious high-pitched buzzing could be heard from afar as I slipped into a light stupor. The burrow is a dream. In the state of hypnagogia, all I could hear was the rising anxiety of the mole. I sensed the swelling panic of the creature, scurrying around, trying to locate the source of the sound with its own pulse. The burrow of the archive, the archive within the burrow.

The shimmering whistle would continue to float in my ambit for days to come, at times ebbing from my feet and trailing behind wherever I went, at other times causing me to stumble, then flying away into the distance and peeking at me from behind one of the nooks of Castle Keep7. What does this acousmatic sound gaze at, so piercingly? The arrhythmic throb of a metronome breaks the syncopation of anxious fatigue. It got foggier and denser in the archive, until I heard the colossal sigh. The third retreat in which I fall out of my slumber.

The sigh felt like a deep cut, an edge which opened into the vast continuity of a hypnagogic state of listening. This is a state adrift between an alert inertness and a wobbly state of ludic awake-ness. The uncanny resonances of fatigued histories– an association of bodies and voices that constituted the archive of the LSI– pulsated with the anxiety of an encounter with the unfamiliar yet known that overwhelmed me. Is it that the listener is like a tapehead activating the record of archived languages in/of bodies or is the shellac record dreaming up the listener with every spin, with truths emerging at the slippages of captured bodies and languages?

Fatigue can produce certain conditions of listening that emerge from within the repetition of its strain. A litany of movements stretches infinitely and suspends the fatigue until it descends into a thick cloud upon which one is afloat and listening. It’s something other than the white noise machines that induce sleep. Neither does it come in shades of pink, black or blue. Perhaps it is closest to a periwinkle noise. A misty buzz that, on one hand, bypasses the state of hyper-vigilance and on the other, steers clear of slinking into a snug hypo-alertness akin to passivity or numbness. Rather it has this angular frequency that produces a parallax and drifts into the subterranean acuity of listening. A double movement of fatigue contains the possibility of tuning out of the regime of calibrated time and mastery into the realm of real and finite instances. This earmarks the composition of a score that falls outside of the ceaseless conveyor belt of real-time.

Movement 4: Muzac

A movement in two instances.

I. The Miner’s Ear

In her essay ‘The Miner’s Ear’, Rosalind Morris invokes the image of the mole and the burrow via Vilakazi’s poem that recites/ resides in the suffocating space between the sounds of the mining machines and the eventual bodily breakdown.8

An excerpt from Vilakazi’s poem (as cited in the essay) that ventures into a mythological narrativisation of the mines-

“one day a siren screeched

And then a black rock-rabbit came,

A poor dazed thing with clouded mind;

They caught it, changed it to a mole:

It burrowed, and I saw the gold…” 9

Rosalind Morries writes– “The whites, observes Vilakazi, were rendered stone by the love of gold, devoid of human affect in their holes, as the (black) moles sent down were reduced to an animal status through the murderous magic of displacement and wage labor.”10

II. The Worker’s Clap

Gene Autry’s 1942 hit ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas’ somehow earwormed its way into the Muzac Inc. playlist for factory workers. These were hours of bespoke playlists designed to keep playing and to control the pace of productivity with their invisible rhythms. This song punctured the assembly line with a resounding clap in its bassline. The factory fell into chaos as all workers paused the operations to clap hands in time with the song’s chorus. The Muzac company’s president later acknowledged, “Once people start listening, they stop working”.11

Etymologically ‘Fatigue’ can be traced to the latin phrase ad fatim— a sense of satiety or a surfeit. In other words, a satisfaction produced via an excess of indulgence. How could a fatigued listening hijack the phantasmagoria of a sensorial excess produced in a system or a structural assemblage? What could it tear up into? A clap. A sigh. A whistle. A scream?

The scream is a curious object of sound, its appearance almost like a sharp cut, an abrupt opening, a counterpoint, an overture, an insertion, an irruption. An ear-splitting scream. The splitting into two is of the time before the scream and the time that becomes of it. A scream is not a yell, it isn’t a shout, it isn’t a shriek. It isn’t also a cry or a howl. A scream is a strange one. It could be bits and parts, sections and wholes of all of these and yet not be like any of these. Its uncountable effects and pulsations signify a material diffusion into an immaterial whole.

I would like to scream but have always found myself unable to. The most I can manage is a shout, a holler, a yell perhaps. I would like to write a scream as the fourth movement towards burrowing into the archive of unsound. It hides in one of the grooves of a record, adjacent to the sigh.

Movement 5: Drifting

The blurs and fragments of the Parable of the Prodigal Son, translated to Urdu and performatively narrated by Baqir Ali in Recording No. 6825 AK12 unfold into this immense sonic landscape of labour. It is an uneasy and breathless topography bubbling with the rhythm of precise renditions, only to be broken by glimpses of contingent utterances.

The dizzying and continuous repetition of the record doesn’t let you hear it until the scratch on its surface meets the fatigued ear. And then one catches it all in a flash as the inexhaustible sigh spills out. Within the crackle and glitches of recorded sound, the exhalation keeps open the discrete aperture in the voice, if only momently.

I often go on these drifts and nibble away at the voices in the air. Is there a name for the dislocation experienced when the sound of a language feels like home and yet resists comprehension? The traces and residues produce a shaky distance which then gets traversed by a scattered listening. What if one is to sing a song yet to be written in the voice of Hassaina or Baqir Ali? A mellifluous refrain that transmits earworms into the years of a future past. They chew on the knots in the archive, breaking it down and releasing more metabolic agents into its burrows. What we have is a ((k)not)archive, that preserves the inaudible duration conjured by each recorded voice at the precipice of sound and unsound.

“All grooved disc media is susceptible to warpage, breakage, groove wear, and surface contamination. Types of surface contamination include: dirt, dust, mould, and other foreign materials, all of which can abrade or damage the grooves and diminish playback sound quality. Excessive surface damage and groove wear are generally identifiable on discs that have a dull surface, scratches, pits, and/or cracks.”13

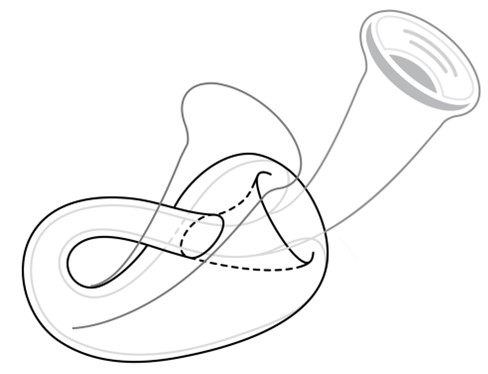

Movement 0 or 5¼ : The Klein Horn

A counter-movement back to the acoustical unconscious of the disc(s). The symptomatic appearances of the scratches and freckles on its surface. Every time it is played, the gashes produce a new sonorous topography and an infinite listening that does not seek but emerges from within the punctures of an abyss.

A macro-zoom into the grooves of the shellac discs containing the constellation(s) of voices, reveals an uncanny resemblance to the inside of a mouth. The gentle curves, undulating surfaces, and palatine folds make room for and generate the conditions for seismic shifts, as the listening body approaches. Palate Tectonics, the theory of geotrauma processed as thoracic impulses and speech acts, proposed by DC Barker14, hearkens back to the rumbles of a past and the futurity of tectonic sounding produced by fatigued listening.

The fifth and a quarter of a movement takes place in the minor occurrence of a sigh. It is carried alongside the light tremors in speech, a stuttering breath, sporadic pulsations and weary strains of the vocal cords. Radiating from an oneiric epicentre, the vibrations invert and scrape out the historical discontinuities occurring across fatigued landscapes beyond merely the geological, anatomical or biopolitical.

Shaped like a trumpet, the winding rooms in the burrow of Grierson’s archive are now infected and laden with a deep and reverberant sigh. The sticky sigh holds a desire to whisper outside of the register of what the phonograph can hear. The air smells pungent and arid.

ENDNOTES

- Kafka, Franz, “The Burrow.” 1992. In The Complete Short Stories of Franz Kafka, edited by Nahum N. Glatzer. Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir, Tania and James Stern. 325-359. London: Vintage.

- Ibid.

- Schuster, Aaron. “Enjoy Your Security: On Kafka’s “The Burrow” – Journal #113 November 2020.” e-flux. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/113/359952/enjoy-your-security-on-kafka-s-the-burrow/.

- Grierson, George A. 1903-1928. “Linguistic Survey of India.” The Digital South Asia Library. https://dsal.uchicago.edu/books/lsi/.

- Calvino, Italo. 2009. Under the Jaguar Sun. Translated by William Weaver. London: Penguin Books, Limited.

- The phrase ‘Hungry Listening’ has been formulated by Dylan Robinson in his evaluation of settler colonial listening modes and perceptions. (Robinson, Dylan. 2020. Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.)

- Castle Keep, in Kafka’s story, is a secret retreat- a burrow within the burrow- which the mole has arduously constructed for safekeeping its stores

- Morris, Rosalind C. “The Miner’s Ear.” Transition, no. 98 (2008): 96–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20204249.

- As cited in Morris, Rosalind C. “The Miner’s Ear.” Transition, no. 98 (2008): 96–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20204249.

- Ibid.

- Blecha, Peter. 2012. “Muzak, Inc. — Originators of “Elevator Music”.” HistoryLink.org. https://www.historylink.org/File/10072.

- Recording No. 6825 AK, Digital archives, Linguistic Survey of India, Gramophone Co.,Calcutta, Europeana sounds, National Library of France, public domain. https://www.europeana.eu/en/item/2059219/data_sounds_ark__12148_cb41483352r

- “PSAP Phonograph Record.” Preservation Self-Assessment Program. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://psap.library.illinois.edu/collection-id-guide/phonodisc.

- Moynihan, Thomas, “TH1. Barker Spoke.” 2019. In Spinal Catastrophism: A Secret History, 57-74. London, United Kingdom: Urbanomic.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Suvani Suri is an artist based in New Delhi. She works with sound, text and intermedia assemblages and has been exploring various modes of transmission such as podcasts, auditory texts, sonic environments, objects, installations, fictions, experimental workshops and live interventions. Her research interests lie in the relational and speculative capacities of listening, voice, aural/oral histories and the spectral dispositions of sound that can activate critical imaginations. Actively engaged in thinking through the techno-politics that listening is embedded in, her practice is informed by the processes of production, mediation, perception and distribution of sound. Alongside, she composes sound for video and performance works and teaches at several universities and educational spaces where her pedagogical interests conflate with a sustained inquiry into the digital and sonic sensorium.