Receiving art with vulgarity

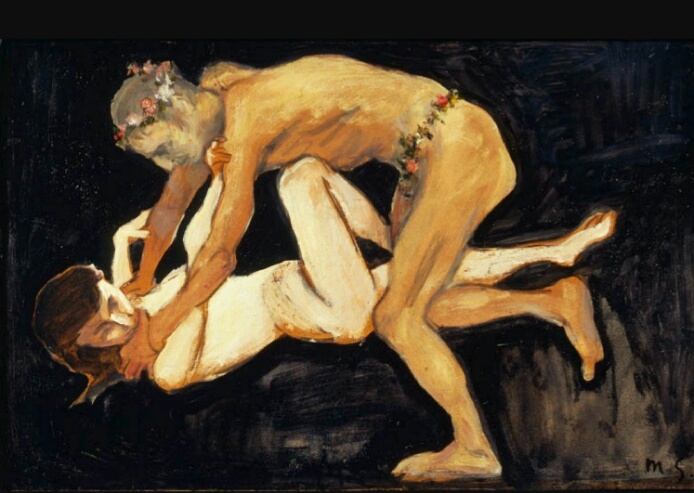

Painting: Faun and a Girl by Max Slevogt Source: Wikicommons

If vulgarity is unrefined or coarse then why do artists bother (if at all they do) intentionally imbibing it? Antonin Artaud’s “Theatre of Cruelty,” sought the ridding of humankind’s repressed energy and rejuvenating them as its purpose. Artaud says in his seminal work The Theater and Its Double (1938), “The theatre will never find itself again except by furnishing the spectator with the truthful precipitates of dreams, in which his taste for crime, his erotic obsessions, his savagery, his chimeras, his utopian sense of life and matter, even his cannibalism, pour out on a level not counterfeit and illusory, but interior.” The inherent repressed desires of mankind are realised through vicarious thrills—be it the gladiators in Rome combating to death, or twentieth century circus where women dressed in raunchy clothes and leaned their heads inside a lion’s mouth. One may smile, make faces or puke through the performance but the eyes want more!

In 1974, Marina Abramovic, a performance artist from Serbia created a performance called Rhythm 0. During the performance Abramovic became willfully passive and stood quietly in the gallery for six hours, during which audience members were invited to use one of 72 objects placed on a table to interact with her. The objects ranged from feathers, chocolate cake, roses, to a pair of scissors, a knife, a gun, bullets and chains. Initially, the audience started with placing a rose in her hand, kissing her, and feeding her cake. It was soon followed by taking scissors off the table and cutting off all her clothes, a man trying to rape her, another loading the pistol and pointing to her head, another man cutting her close to neck and drinking her blood. She stated, “After six hours, which was like 2 in the morning, the gallerists came and announced that the performance was over. I started moving and start being myself, because until then I was there like a puppet just for them, and at that moment everybody ran away. People could not confront me as a person.” 5 To see a silently standing artist, and however anointing or disfiguring her was at the audience’s discretion alone.

- Aamir Butt, “Manto: The tormented genius” THE NATION, January 18,2016,

https://nation.com.pk/18-Jan-2016/manto-the-tormented-genius - Navarasa: The nine emotions widely accepted in Indian art aesthetics

- The research was commissioned by Encore Tickets where the team monitored heart rates and electro dermal activity of 12 audience members at a live performance. The team found that alongside individual emotional responses, the audience members’ hearts were also responding in unison, with their pulses speeding up and slowing down at the same rate.UCL,” Audience members’ hearts beat together at the theatre” (November 2017),

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/pals/news/2017/nov/audience-members-hearts-beat-together-theatre#:~:text=New%20research%20led%20by%20the,you%20know%20them%20or%20not. - Freedom Cole, “The nine affects and the Navarasa” (March 2015),

https://shrifreedom.org/ayurveda/rasa-and-bhava/ - Natalia Borecka,“The Most Terrifying Work of Art in History Reveals The True Cost of Passive Acceptance”LONE WOLF MAGAZINE, April 16,2016,

https://lonewolfmag.com/most-terrifying-work-of-art-passivity/amp/ - Apsara: Celestial Nymph

- Bhavana Akella, “Khajuraho temples defined India globally as Kamasutra land” DECCAN HERALD,September 8, 2015,

https://deccanherald.com/amp/content/499793/khajuraho-temples-defined-india-globally.html