Ṣadā: Her-story and Echoes of Nationhood

AUTHOR

Shweta Sachdeva Jha

fazā ye amn-o-amāñ kī sadā rakheñ qaa.em

suno ye farz tumhārā bhī hai hamārā bhī —Nusrat Mehdi1

To protect the peace around us forever,

Listen, this is our duty, both yours and mine.

This year, India completes 75 years of independence as a nation-state, while our perception of our nation-scape/nationhood becomes increasingly fractured and polarised. Women are in positions of power as well as agents of protest2 but where do they figure in our recollections of our past? And can that past be audible? This essay is a woman educator’s self-conscious response as she listens to a contemporary poetess and her she’r.

The Urdu word sadā can be written in two different ways although, when spoken, they sound the same;

سدا (Sadā) means ‘always’

صدا (Ṣadā) is ‘echo or call’

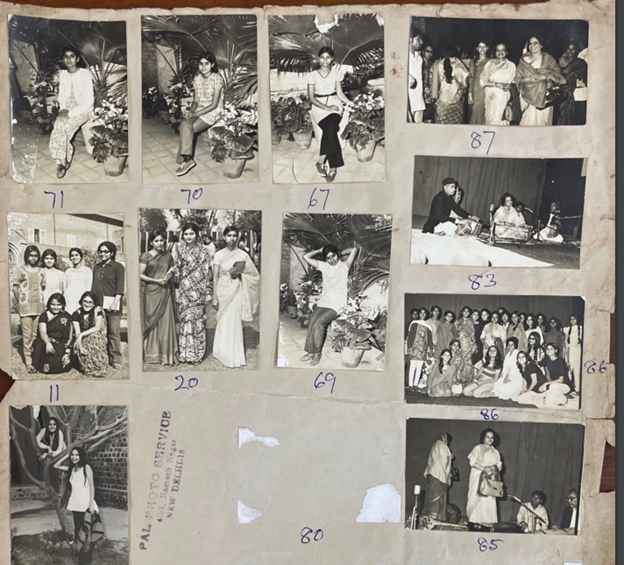

Moving from the first interpretation used by Mehdi to the second one, in this essay, let us listen to the echoes/calls of or by women in the past. I teach in Miranda House, a women’s college in the University of Delhi and I have spent the past few years pondering over college-going women’s archives and histories.3 Starting as a personal project and then growing into a collective, we have been documenting experiences of college-going women through their writings, photographs, and oral histories (via recordings) since 2019. A microcosm within the soundscape of the nation, Miranda House was founded in 1948.

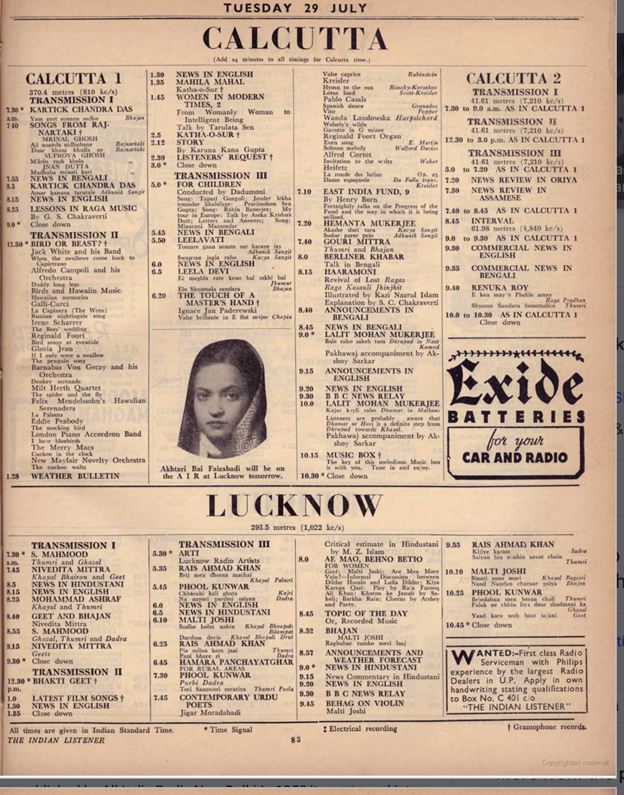

While young women thronged to colleges for higher education, Lata Mangeshkar’s (1929-2022) voice enthralled the audience of Hindi cinema in films such as Andaz, Mahal, and Barsaat in 1949. She ‘not only embodied the nation but sang the nation’.4 At the same time the strains of the soulful ghazals of Begum Akhtar (1914-1974) were audible on the All India Radio the same year. Initially known as Akhtari Bai Faizabadi, she had performed on stage and in films as a famous tawa’if singer5 earlier. But her marriage to Ishtiaq Ahmed Abbasi in 1945 meant she was no longer free to perform. In 1949, Begum Akhtar finally returned to the sound waves. She was the ‘Queen of Ghazals’ while Mangeshkar became the ‘Queen of Melody’. With the backdrop of the Indo-China War hanging over the Republic Day Celebrations in 1963, Mangeshkar’s rendition of ‘Ai mere watan ke logon’ would ultimately mark her indelible presence in the sonic history of our nation-scape.6 But how did women respond to these singers?

Begum Akhtar had performed at Miranda House on 7th March 1974, the 26th founder’s day of the college when many young women listened to her in rapt attention and awe. Although musical knowledge and tradition are often assumed to be patrilineal and gharana-centric, women like Akhtar had women shagirds (student/disciple)).7 Rekha Surya, an alumna of the college, had become her student in 1972. Akhtar passed away in October 1974 but an interview recorded in 2021 revealed the fondness with which a shagird recalled her guru and the unique experience of having memories and musical knowledge be shared and passed on between women.8

Beyond music and recording artists, listening to women’s memories or building sonic archives can deepen and interrogate our understanding of nationhood in ways that written texts often cannot.9 A fascinating instance of how listening unravels the gendered soundscape of our past lies in the life-history of Usha Mehta (25 March 1920 – 11 August 2000) and the case of the secret Congress Radio.

The story of the soft-spoken Usha Ben (‘ben’ for sister), a young girl of 22 in 1942, has now been published by her former student, Usha Thakkar, who compiled it from conversations and texts. Both these women later retired as academics from the SNDT Women’s University, Mumbai, again reminding us of how women’s colleges are significant though neglected sites of shared memories and sound histories.10

Responding to Gandhi’s call for the Quit India Movement in the year 1942, a group of young men and women, including Usha Ben or Radio Ben as she would be called later, initiated the idea of a radio station and a transmitter. Their efforts led to the Congress Broadcasting Station with its own transmitter, transmitting station, signal, and distinct wavelength. The broadcast went on air at 8.45 PM and was announced by the Bombay Congress Bulletin on 3rd September 1942. These programmes were a nightly event broadcasted from Bombay at 42.3 metres’ wavelength, though Radio Ben announced that they were speaking ‘somewhere from India’. Morning programmes and recordings of ‘Hindustan Hamara’ and ‘Vande Mataram’ were played on the radio. This continued till 12th November 1942 when the station was seized in operation by the British and the team arrested. Usha Ben was imprisoned for 4 years. The radio had been a major means of communication during the Second World War11, but Usha Ben forged our anti-colonial nationhood upon the anvil of the radio and made it a medium of protest.

Interview with Usha Mehta, posted on August 2017

Courtesy: The Press Information Bureau, Government of India

On the eve of Independence in 1947, Saeeda Bano started broadcasting with All India Radio in Delhi and became the first woman Urdu newsreader during the turbulent time of freedom and Partition. Bano’s immaculate Urdu diction made its way through the airwaves and into the homes of the newly minted citizens of Independent India.12 She was one of the many women broadcasters all over the world, a sonic marker of the women’s movement and feminist struggle in the twentieth century.13 Across the newly carved borders of the Indian subcontinent, the soundscape was shaped by women newsreaders, announcers, singers, broadcasters, and performers at radio stations in Lahore, Jalandhar, Lucknow, Madras, Delhi, Mumbai and many other cities and towns.14 Begum Akhtar, Usha Mehta, Saeeda Bano and Lata Mangeshkar belong to a long lineage of women who deftly used sound technologies to shape the sounds of a fledgling nation.

To trace this diverse lineage of sonic interventions by women, we need to shift our focus from sound-production and broadcasting to include listening practices. As we get inundated by multimodal content, the diversity of women and our pasts will become audible15 only if we turn into nuanced and discerning listeners and archivists of memories. Beyond the raucous noise of an enforced, singular nationhood lies a mellifluous, lyrical, and robust sonic past shaped by myriads of women if only we would listen.16

NOTES

- Her poetry can be followed at https://www.rekhta.org/couplets/fazaa-ye-amn-o-amaan-kii-sadaa-rakhen-qaaem-nusrat-mehdi-couplets

- Currently there are 11 women in the Cabinet Ministry and our President now is an Adivasi woman, at the same time throughout anti-CAA Protests, Sabrimala Temple Entry, Hijab controversy in Karnataka schools, women have been fighting against oppression.

- https://mirandahousearchive.in/. I gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr Avabai Wadia and Dr Khurshedji Wadia Archives for Women Fellowship (2020) to start the project. I lead the Miranda House Archiving Project team and it was started in 2019. Initially a personal project it has now become a collective team of teachers, non-teaching men and women, students and alumni. For more see the website.

- Vinay Lal, ‘Singing the Nation’ Open Magazine, 11 February 2022. https://openthemagazine.com/cover-stories/singing-the-nation/

- The history and contribution of tawa’if singers as recording artists is richly documented now both through textual and audible resources. See https://ignca.gov.in/Begum_Akhtar/index.html For more on Vidya Shah’s project on women recording artists see https://ncaa.gov.in/repository/search/displaySearchRecordPreview/IGNCA-AC_1382-AC/Lecture-on-Women-on-Record-Contribution-in-Music-(Vol.-I)

- Lal, Singing the Nation.

- Shanti Hiranand, Begum Akhtar: The Story of my Ammi (Viva Books, 2005).

- Oral History transcript, online interview of Dr Rekha Surya taken by Gayatri Punj, Devika Gupta 18 February, 2021, pp. 1-2 (Miranda House Archiving Project).

- For use of oral history see Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (Penguin Random House, 2017).

- I am grateful to the MHAP intern Jaya Narayan for informing me about Usha Mehta. Usha Thakkar, Congress Radio: Usha Mehta and the Underground Radio Station of 1942 (India Viking, 2021).

- In May 1940 the All India Radio had done listener based research in five major cities across 13, 507 listeners and found that more Indians were using the radio to listen to news hostile to Britain. Ibid.

- Saeeda Bano, Off the Beaten Track: The Story of My Unconventional Life trans. Shahana Raza (Zubaan and Penguin Books, 2020).

- See Christine Ehrick, ‘Radio and the Gendered Soundscape’, in Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay, 1930–1950, Cambridge University Press, 2015 pp. iii -iv.

- Begum Akthar was often called Akhtari Bai too. The radio magazine published by AIR is a great source to see how women singers like Akhtar performed so often on the radio for different stations. For example see The Indian Listener (April 21, 1957 pgs. 13, 20, 27, 39, 41, 44) https://worldradiohistory.com/INTERNATIONAL/Indian-Listener/50s/The-Indian-Listener-1957-21-04-1957.pdf

- Sound is the basis of our foundational knowledge and modernity is linked with sound as it becomes commodified and measured. See Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 2-3.

- I am thankful to my student Akshika Goel for her comments on this piece.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shweta Sachdeva Jha teaches English at Miranda House, University of Delhi. She won the Felix Scholarship to study for a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Her interdisciplinary interests range across women’s history, children’s picture books, Urdu popular literature, and digital archives. Parts of her thesis on the tawa’if have been published as chapters in Speaking of the Self: Gender, Performance and Autobiography in South Asia (Duke University Press, 2015) and The Bollywood Islamicate: Idioms, Histories and Imaginaries (Orient Blackswan, 2022). Her chapters on women’s writing in Urdu can be read in South Asian Gothic: Haunted Cultures, Histories and Media (University of Wales Press, 2021) and Sultana’s Sisters: Gender, Genres, and Genealogy in South Asian Muslim Women’s Fiction (Routledge, 2021). Her awards include the Avabai Wadia Fellowship by SNDT University of Women, Mumbai (2020) and the Tata Trusts-Partition Archive Research Grant (2021).