Technology, Obscenity, Leisure: The Case of the TikTok Ban

It took a ban for TikTok to really become an object of interest for the mainstream media. On 3 April, 2019, a bench of the Madras High Court passed an interim order directing the Centre to prohibit further downloads of the TikTok mobile app; to prevent broadcast media from sharing content created on the app; and to consider provisions for the safeguarding of children’s privacy online on the model of the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act in the US. In the steady uptick of reports, opinion pieces and explainers that followed the banning of the app, it became evident that a cultural object that had caused sufficient consternation among members of civil society and lawmakers as to warrant urgent regulation, had actually passed below the radar of many. Recurring themes emerged in this press coverage – how TikTok had lately emerged as the favourite pastime of youngsters; how it had become a source of a new crop of influencers and content creators; and most crucially, how its domain had so far remained limited to the Indian small town, or to put it as one commentator did, evidently addressing an elite readership, “non-PLU types” (People like us). What became apparent in this retrospective effort to make sense of the app, was that a technological artefact charged with “encouraging pornography”, “degrading culture”, “causing paedophiles”, and spreading “explicit disturbing content” did not have the uniform cultural salience the High Court judgement would suggest. One cannot imagine, for instance, a similar flurry of explainers of what Instagram or Facebook is in the unlikely event that either social media platform were banned. It is in this contradiction between the app’s simultaneous popularity and anonymity that the anxiety around TikTok and its cultural invasion can be better understood.

There are precedents for this latest moral panic around a piece of technology. William Mazzarella has written extensively about the censorship boom in India concomitant with the explosion of commercial media post economic liberalization. Scandals caused by the circulation of amateur videos like the Mysore Mallige clip in 2001, or the 2004 Delhi Public School MMS, have attracted considerable scholarly attention. Indeed, the ur-technology prompting fears of cultural contagion was the cinema, which as Mazzarella observes, for the first time offered the chance of belonging to a mass public without being literate. The current furore around TikTok has much in common with these past instances of technophobia in relation to new media, and as such, seems to rehearse a debate that is at least a century old.

Like the earlier fears around cinema and the MMS, the anxiety surrounding TikTok is tied to the technology-as-such, rather than its particular content. Anirban K. Baishya in his study of the MMS form, notes how the iconicity of high profile cases has identified what is an aspect of cellphone technology with a genre of pornographic video, and rendered the mobile itself a libidinal symbol. The cultural denigration of cinema also has always hinged on its particular implication of the body in the act of watching films – any film. The Justice G. D. Khosla Committee on Film Censorship (1969) referred to film’s evocative potential, and its tantalizing ability to swap the viewer’s reality with the world presented on screen. In a similar vein, TikTok is indicted for its “addictive” quality and for leading children and indeed adults to waste their time on what is deemed a frivolous distraction. The incoherence of the judgment citing a host of phantom threats ranging from the exposure of children to strangers, “cruel humour against innocent third parties”, and even a reference to national security being jeopardized, suggests that what is truly at stake in the app’s popularity is the inability to regulate an innately unruly cultural object.

In this sense, TikTok troubles the already ambiguous legal definition of what qualifies as pornography, exemplified by the pithy summary offered by a US judge – “I know it when I see it”. The problem with TikTok is that it doesn’t precisely allow you to see. The ephemeral nature of the app, with short videos appearing momentarily and disappearing with a swipe of the screen, means that content exists in a state of constant circulation and dissipation. It is virtually impossible to apprehend an offending TikTok video unless it has been archived on other platforms, like YouTube and Twitter. It is further impossible to replicate an individual user’s trajectory on the app, dependent as it is on the idiosyncrasy of the algorithm. What is held objectionable in this absence of the discrete pornographic object, is the enabling nature of the technology itself to feed troubling tendencies among a vulnerable demographic. Namita Malhotra, in her pioneering monograph on the imbrication of pornography, law and technology in India, notes that the law has cultivated a strategic blindspot around illicit material, leaving it to be administered by other disciplinary structures like the family, school, office, etc. The expansion of technology, enabling access to both material and the means of production and distribution, forces the law to take note of what is otherwise “an open secret”. What technology endangers is thus the integrity of other societal institutions and regulatory mechanisms, requiring the law to step in, and in the process, show its own hand. Malhotra quotes Nishant Shah, according to whom “The State’s interest in pornography, then, is not in the sexual content of the material but in the way it sidesteps the State’s authorial positions and produces mutable, transmittable and transferable products as well as conditions of illegalities and subjectivities.” It is telling that the High Court in its criticism of TikTok, made reference to another infamous scandal, the Blue Whale Challenge, a largely apocryphal social media phenomenon tenuously linked to a string of teen suicides in the country in 2017. The invocation of Blue Whale along with the inchoate host of concerns flagged in relation to TikTok indicate a sense of impotence in the face of the elusive, insubstantial and cryptic nature of networked communications, and a consequent desire to reclaim lost mastery. What is obscene about TikTok, then, is the way it forces the law and the state to expose themselves.

In the event, the act of censorship becomes a means of restoring the state’s powers of regulation. Mazzarella discusses this in the context of the obscenity debates in the years immediately following liberalization. He notes, “On the one hand, liberalization was all about liberation… On the other hand, this liberation had to follow approved pathways, to be channeled into consumer brand worlds and identitarian, often chauvinistic, political affirmations.” He then contends, that in this context, censorship rather than proscribing desire, actually seeks to direct and therefore delimit desire which would otherwise overflow acceptable bounds. This might also explain what Malhotra elsewhere sees as the curious decision of the law to fixate on relatively innocuous, even inoffensive material in the cases where it must determine obscenity. Such a deflection of attention amounts to an averting of eyes, maintaining what she regards as the law’s habitual blindness – and therefore elevated distance – to abject material even as it extends its jurisdiction across new cultural sites. Whether in the case of the 2004 MMS scandal, where an individual Avnish Bajaj, the CEO of Bazee.com, was sought to be booked for the sale of the clip, or TikTok, where the parent company Bytedance was charged with the dissemination of pornographic content, the failure to pin down the culprit is compensated by redirecting the charge of criminality with the ultimate McLuhan-esque flourish – the medium is [conflated with] the message. Further, in choosing to prosecute TikTok as one-off cultural malware, the law leaves unaddressed a wider landscape of corporate media including Google and Facebook, which several commentators point out similarly act as gatekeepers of information.

Mazzarella’s study of fin-de-siècle media configurations in India is especially pertinent to an analysis of TikTok and its seemingly universal condemnation in an otherwise polarized public discourse. Writing about a time in history when the forces of globalization ran apace with currents of religious revivalism, Mazzarella noted how what initially presented itself as a gulf of public opinion between a cosmopolitan Left and the conservative Right, actually revealed an agreement in principle about the democratic potential of media. Taking a historic view of film censorship in India, he found that both liberal and reactionary sections of the middle class were united in a common attitude of paternalism towards subaltern audiences of the cinema. This was a class of spectator whose enjoyment of film was considered to subsist in a mimetic attachment to the screen, rather than the critical, disinterested engagement of the educated viewer. The insufficiently developed mental capacities of illiterate Indian audiences justified censorship, where in the political arena, it stopped just short of (but continued to tease the fantasy of) a benevolent dictatorship of the elite. In a post-colonial developmentalist schema, then, the problem of education haunted everything from film culture to political democracy. The coming of liberalization, however, caused a shift in the criterion of citizenship, making the imperative to consume the primary responsibility. And “the voluptuous idiom of consumerism” was one that bypassed the social capital and intellectual labour of education.

The criticism of TikTok seemed to similarly unite individuals on both sides of the spectrum. The initial calls to ban the app, including debates in the Tamil Nadu State assembly typified right-wing reaction to the perceived degradation of Indian culture by modern media. But several liberal commentators also chimed in with their disapprobation of the app’s encouragement of unproductive and silly behaviour. Thus, a similar argument was made albeit from different perspectives – the Right, as ever, took up cudgels on behalf of tradition, while the progressives mount a critique of taste.

Here, a further sense of obscenity is flagged. Why, for example, are the productions on TikTok considered offensive when the Bollywood templates to which they refer have become naturalized to the point of becoming banal? I would argue that TikTok is considered vulgar, not only because of the content of individual videos and their lo-fi, DIY aesthetic, but also, and this seems to be of essence, because the app encourages people to waste time and resources. This flies in the face of the old capitalist axiom – time is money! The spectre of such squandered productive capital is extended to the TikTok user himself, who as one journalist derisively remarked, represented the country’s proverbial “demographic dividend”. This is the millennial generation dubbed “the Dreamers” by reporter Snigdha Poonam, who comprise the largest potential youth workforce in history. Widely considered to constitute India’s prime economic advantage on a world stage, especially vis-à-vis neighbouring China, it is a demographic that has been ill-served by a slowing economy and diminished prospects of lucrative employment. Without a job, Indian youth are thought to spend endless, listless hours on TikTok, either creating or consuming mindless entertainment. And to add insult to injury, they are entrapped by an app owned by the very economic rival they were supposed to help edge out in global competition. TikTok, as an unofficial index of unemployment, unfolds in real-time the obscene spectacle of the attrition of national economic potential.

Change.org petition started by user Rocky Superstar. Screenshot taken by author.

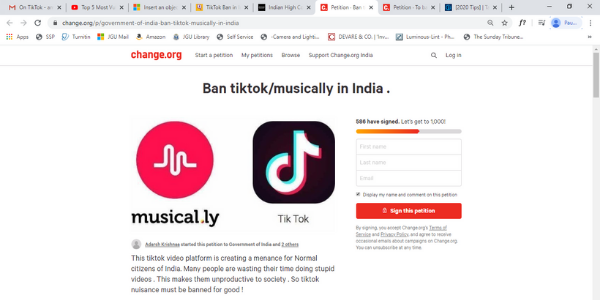

Change.org petition started by user Adarsh Krishnaa. Screenshot taken by author.

The cardinal sin of TikTok, then, is revealed to be the way in which – to put it in the words of The New Yorker’s Jia Tolentino – it “doesn’t ask you to pretend that you’re on the Internet for a good reason.” Or it can be considered symptomatic of what The Economist reports of Internet use in India – that the poor are increasingly persuaded to come online in pursuit of pleasure rather than older developmentalist imperatives. But what such interpretations fail to take stock of is the way in which leisure activities increasingly encode a form of latter-day capital. TikTok, encapsulates the logic of a post-Fordist economic order, where the separation of work and non-work is increasingly disturbed by the colonization by capital of all aspects of life. The idea of play-as-labour is central to the use of TikTok by the small-town, vernacular user, who deprived of other avenues, is acutely attuned to the app’s productive possibilities. What an educated class bemoans as the decline of creative standards is then actually an admission of insecurity – of the repudiation of specialised knowledge and expertise, and the consequent, revolutionary opening of the gates.

To return at the end to the point with which I began, the censorship of TikTok elucidates its cultural meanings. The belated “discovery” of TikTok by a literate and otherwise media-savvy class indicates the way in which this class is actually out of step with the manner in which labour, capital and pleasure are mutually implicated in a ludic rather than utilitarian economic order. In the chasm between the public who only took stock of its impact after the ban, and its early adopters who are conspicuous by their absence in public discourse, the subversive potential of TikTok is emphatically registered.

References:

- Bagchi, Shrabonti. “TikTok users don’t care for your opinion.” In Mint Lounge, April 19, 2019. https://www.livemint.com/mint-lounge/features/tiktok-users-don-t-care-for-your-opinion-1555642988767.html

- Baishya, Anirban K. “Pornography of place: Location, leaks and obscenity in the Indian MMS porn video.” In South Asian Popular Culture, 15:1 (2017), pp. 57-71.

- Emmanuel, Meena. “‘The future of youngsters and mindset of children are spoiled’, Madras HC directs ban on mobile app TikTok.” Bar and Bench, April 3, 2019. https://www.barandbench.com/news/madras-high-court-ban-tiktok

- Ghosh, Poulomi.”5 reasons why I think TikTok should be banned.” In DailyO, February 22, 2019. https://www.dailyo.in/humour/pulwama-rss-5-reasons-why-tiktok-should-be-banned/story/1/29602.html

- Grover, Gurshadabad. “Why the TikTok ban is worrying.” In The Hindustan Times, May 2, 2019.https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/why-the-tiktok-ban-is-worrying/story-9Q7Gpv9t1Uxavd8hYJnjDO.html

- “How the pursuit of leisure drives internet use.” The Economist, June 8, 2019. https://www.economist.com/briefing/2019/06/08/how-the-pursuit-of-leisure-drives-internet-use

- “India TikTok Ban: App Removed From Google, Apple Play Stores.” Livewire.com, April 17, 2019. https://livewire.thewire.in/out-and-about/tiktok-ban-google-apple-play-store/

- Malhotra, Namita. Porn: Law, Video, Technology. Bangalore: Centre for Internet and Society, 2011.

- Mazzarella, William. “The Obscenity of Censorship: Rethinking a Middle-Class Technology.” In Amita Baviskar and Raka Ray eds. Elite and Everyman: The cultural politics of the Indian middle classes. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Poonam, Snigdha. Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing Their World. Penguin Random House, 2018.

- Pundir, Pallavi. “Indian High Court Wants to Ban Chinese App TikTok for ‘Encouraging Pornography’.” Vice.com, April 4, 2019. https://www.vice.com/en_in/article/qvy7zp/indian-high-court-ban-chinese-app-tiktok-for-encouraging-pornography

- Sathe, Gopal. “From TikTok And PUBG To Github And Reddit: Behind India’s Internet Bans.” Huffpost, April 16, 2019.

https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/tiktok-pubg-github-reddit-india-internet-ban_in_5cb45248e4b082aab08886f2?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAALALS8NIDcByRm8u752gzbMcf3y0GptpmXekXgihUb2C1JIsd2ip2XYu698TtzJ80Ts1J5PQwFOXMCQdGgTJykD9jvxqZ1iQ4oeFhSenRSMuWvg7BccyRjNUifU8MJczzGL0e_JoO8B06x1DnhpYeQJ7XUs6sr5zLNsUs-zcNqtO - Shaviro, Steven. “Accelerationist Aesthetics: Necessary Insufficiency in Times of Real Subsumption.” e-flux Journal #46, (June 2013).

- Tolentino, Jia. “How TikTok Holds Our Attention.” In The New Yorker, September 23, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/09/30/how-tiktok-holds-our-attention

About The Author

Amrita Chakravarty is a graduate of the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU. A Cinema Studies student, her MPhil dissertation entitled “Expanding the Archive: Re-iterations of Film(i) History in Contemporary Media, Art and Cinema” looked at the diverse uses and manifestations of film history prompted by the proliferation of digital archival practices. Drawing from the fields of retro and nostalgia studies, and media archaeology, her research included a case study of social media, specifically digital platforms like TikTok and Dubsmash as new sites of fan activity and film discourse. She has been at Critical Collective since 2017, where she is now a Senior Researcher in charge of CC Cinema. She has previously written for BLink and ArtDose magazines.