The Botanical Imagination

It is a truth now universally acknowledged, not least in recent articles in The Guardian and the BBC that the extinction of plants spells “bad news for all species,” and is being rapidly exacerbated by human destruction of the natural world. According to Dr Rob Salguero-Gómez from the University of Oxford, plants provide us with “food, shade and construction materials,” as well as “‘ecosystem services’ such as carbon fixation, oxygen creation, and even improvement in human mental health through enjoying green spaces.”

With the irreplaceable role of plants in our lives and surroundings, it is no surprise that artists have continually depicted the botanical world for both aesthetic and documentation purposes. Poised between art and science, botanical art has both aesthetic and utilitarian value. In India, this genre is largely associated with the Kampani (Company) school of painting, a naturalistic Indo-European style that became prevalent in the late 18th century when the East India Company sought to document the flora of the country. But depictions of plants go back much further in Indian art history, and were seen “on temple walls, pottery designs, motifs on woven carpets and embroidered textiles, […] illustrated folios from medieval manuscripts of Hindu epics,” and detailed in highly stylised forms in miniature art.

It is not only plants that face extinction. In Marg magazine’s recent issue (December 2018 – March 2019) titled Ars Botanica: The Weight of a Petal, historian and curator Sita Reddy says, “Today, with botanical art disappearing by the archive, and trees, forests or entire ecosystems at the whim of a malicious executive order, it seems more urgent than ever to compile some of these dispersed art historical resources. To refigure the botanical archive.”

While Marg drew attention to the rich, vibrant and largely unacknowledged history of botanical art in India, this essay seeks to explore the work of three contemporary Indian women artists who use plants as a motif, medium and metaphor to comment on issues of both personal and global significance. Belonging to a generation that has been educated in various sciences, the “diversity of interest [of these artists] allows for an exploration of the transcultural through the lens of the sciences, which function in a “universalist” sense wherever science is practiced – even if context favors one direction over another.” Incorporating but looking beyond aspects such as documentation and revival, the artists explore the botanical as an inquiry and a recreation of memories, reminding us of the value of our ecosystems and why we should be concerned about their loss.

GARDENS FROM THE PAST

For Samanta Batra Mehta, nature is “a metaphor for the body (and vice-versa) and as a site for germination, nourishment, degradation, trespass, plunder, colonisation and transgression.” Though the plant forms she depicts are an artistic rendering rather than an exact replica, they are informed by historical botanical illustrations, and by observing the plants in places where she has travelled and lived, including Mumbai and New York.

Mehta also draws upon accounts and memories of the ornamental and kitchen gardens created by her grandfather – a botanist, college professor and agricultural scientist who fled violence during the Partition of 1947 – which he had to leave behind and eventually nurtured again in North India. Mehta says that “these fantastical gardens conjured by my families’ collective imagination, the larger debates underpinning them and themes in my own migration to New York appear frequently in my art.” She pays homage to her grandparents’ journey in Return to the Garden, 2019, where she “transcends time” by superimposing botanical and anatomical drawings, symbolising life, in red ink on vintage photographs and antique book leaves.

Samanta Batra Mehta, (top) Return to the Garden; (bottom) detail images, 2019, ink drawings made with hand dipped stylus, vintage/antiquarian photographs, book pages, map (20 parts), installation variable, approx. 75 x 75 inches. Photo courtesy the artist and Tarq Gallery, Mumbai

PAGES WITH PRESSED FLOWERS

A GREENHOUSE OF POSSIBILITIES

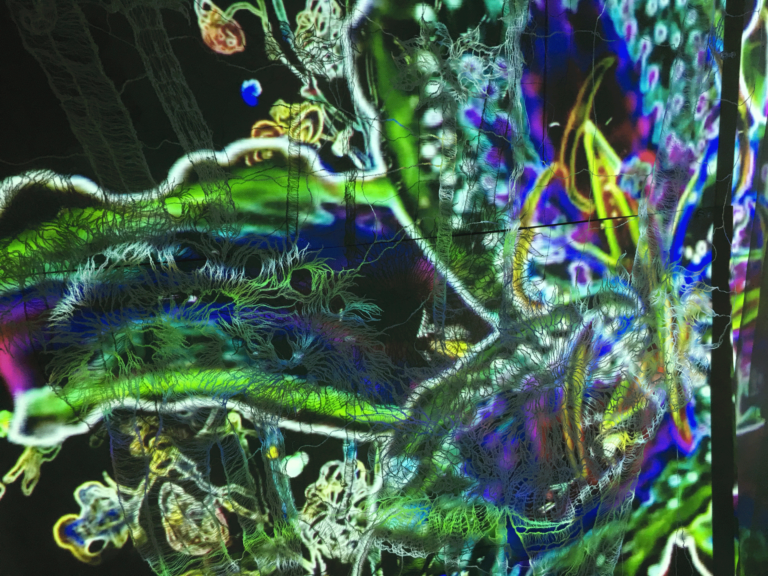

Elsewhere, Devasher said that she had been “exploring some ideas put forward in Goethe’s Botanical writings in which Goethe’s search for “that which was common to all plants without distinction” led him to evolve a purely mental concept of the archetypal plant. This archetype, when translated into art by some of his followers, resulted in what one writer has described as a ‘botanist’s nightmare’ consisting of all known leaves and flowers combined around a single stem. […] What result are hybrid organics that float in a twilight world between imagined and observed reality…forms in constant flux, in a state of continuous transformation. They could be denizens of a science-fictional botanical garden, specimens in a bizarre cabinet of curiosity or portents of a distant future.”

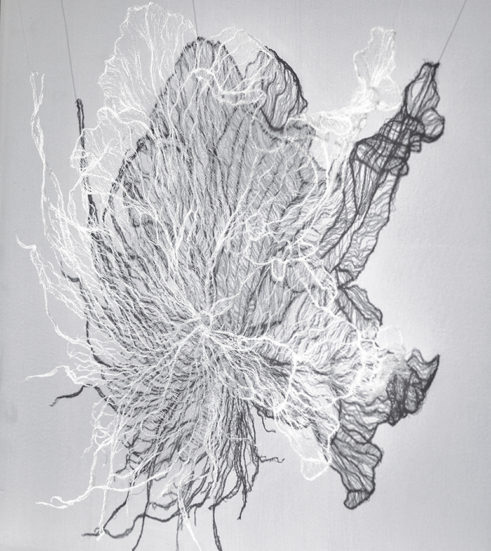

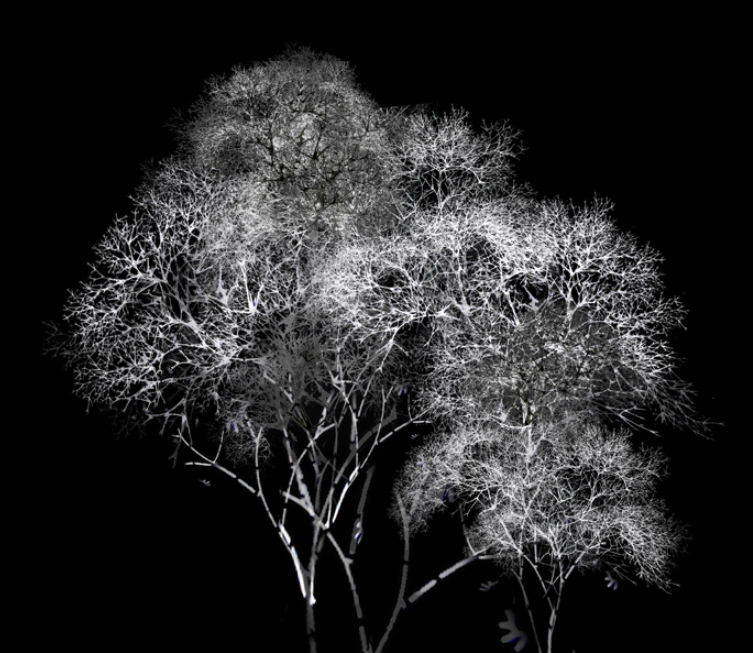

Interested in patterns, Devasher thinks of the botanical as a way to explore the mathematical in an engaging manner. In Arboreal, 2011, a video and photography-based work, the artist draws upon the Lindenmayer system of modelling plant growth and development. The recursive nature of the system creates branching, or fractal forms reminiscent of trees in the natural world. According to an exhibition statement by gallery Nature Morte, “If we consider the Arboreal video to be the archetype or ideal tree, then the Arboreal prints are a window to the other trees that could also have been. Once again these are generated by the layering of selected still frames of video, stacked one on top of the other. What results is a digital forest, a greenhouse of possibilities.”

The speculative or science-fictional perspective is explored in works such as AtlasPhaenogamia or the Atlas of Mimetic Flowering Plants, 2018 and the Genetic Drift series, which are as much about botanical accuracy as subverting it to consider a new visual vocabulary altogether. Atlas draws from specimens found in the R. L. McGregor Herbarium at the University of Kansas, deposited as far back as 1893, but the artist alters them to resemble varied animal forms. The process of creation involved photographing the specimens, and then modifying the images using Photoshop, pencils and acrylic. The series Genetic Drift presents hybrids – layered composites created using nearly 300 photographs and drawings collected by the artist in botanical gardens across the world.