The Course of a People’s Land

AUTHOR

Satyam Yadav

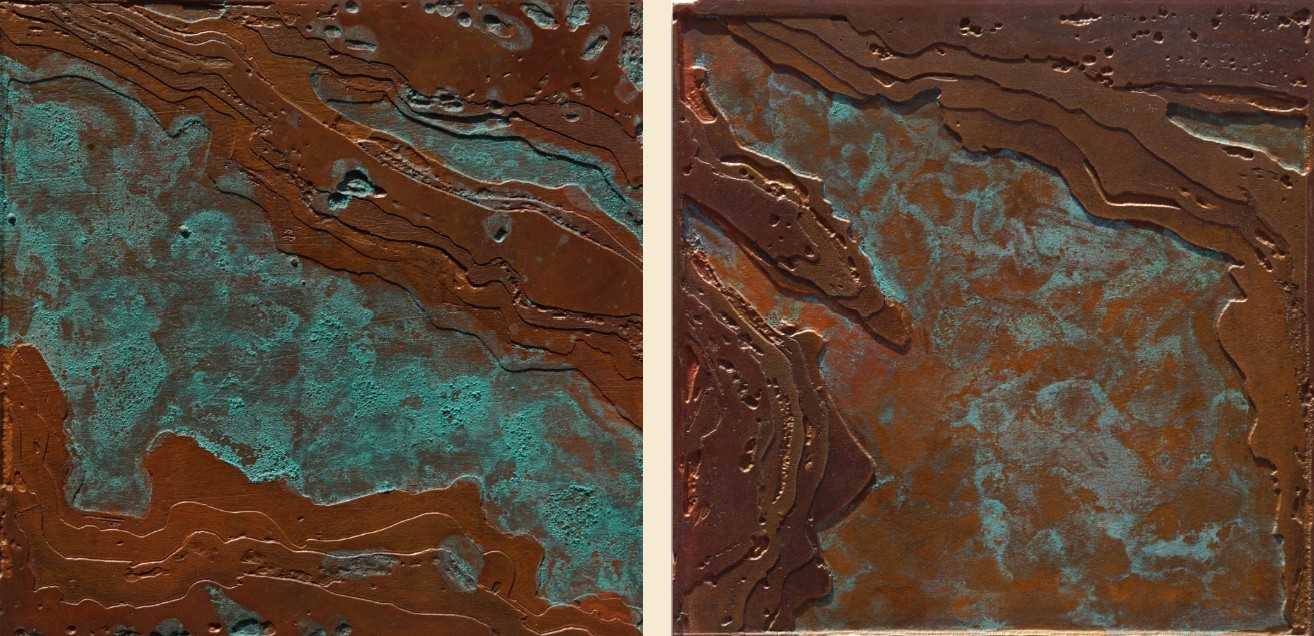

Earlier this year, amidst some exceptional practices on view in a group exhibition at the SOAS Gallery in London,1 I came across a familiar artwork — or a close version of it — that I remembered seeing a long time ago in Delhi. Seemingly an aerial view of an open-pit mining site, each iteration was uniquely reproduced in a grid of about 30 copper plates, mottled with pools of striking blue-green patina filtering out from seams across its metallic surface. Like before, I found myself deeply intrigued by the materiality of the work – not to mention the peculiar rendering of the landscape.

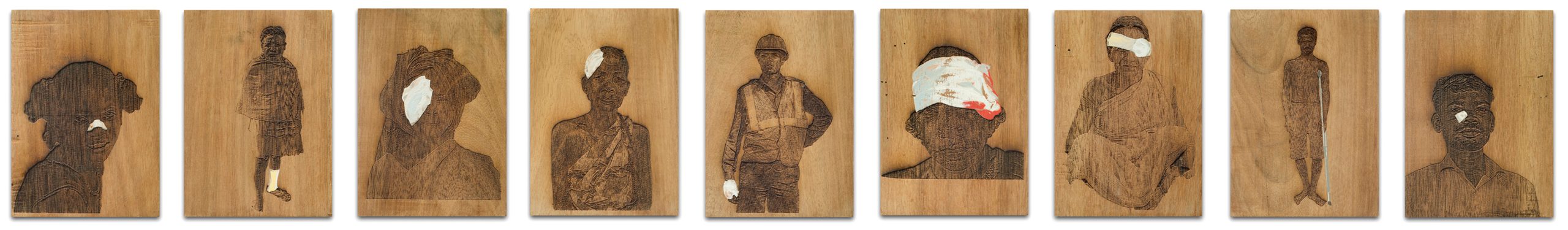

Barren mine sites are a recurring image in artist Sangita Maity’s (b.1989) multimedia practice, which spans photography, photo-etchings, serigraphy, woodcuts, and more. Moving between portraiture and scenes from everyday life, Maity examines how forces of statist extractivism — including mining, hydroelectric projects, and industrial farming — overlap with labour conditions and cultural disembodiment of tribal communities, alongside environmental degradation across the states of Jharkhand, West Bengal and Odisha.

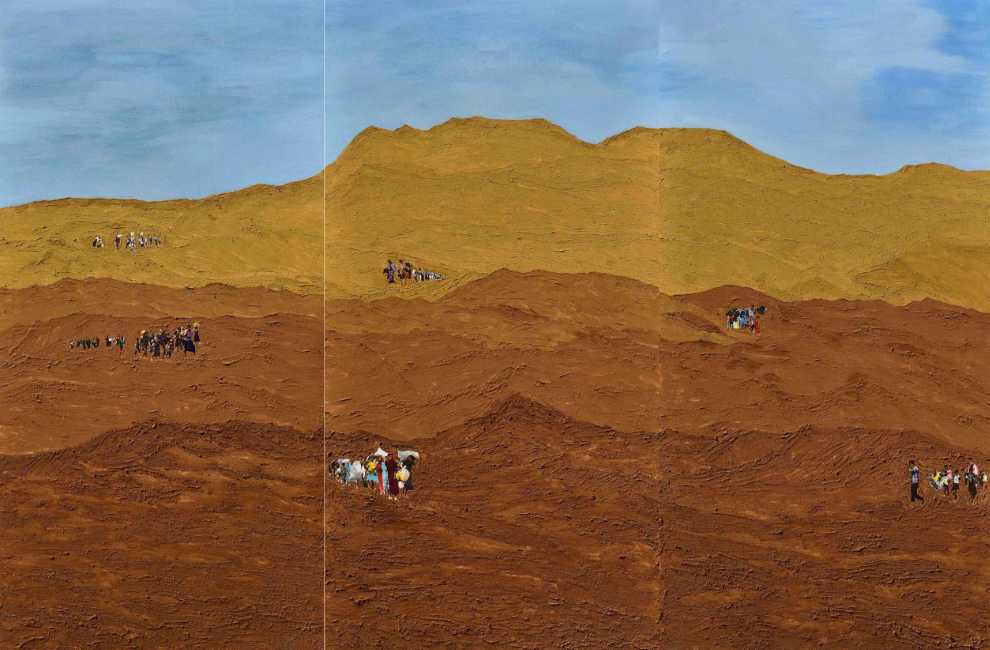

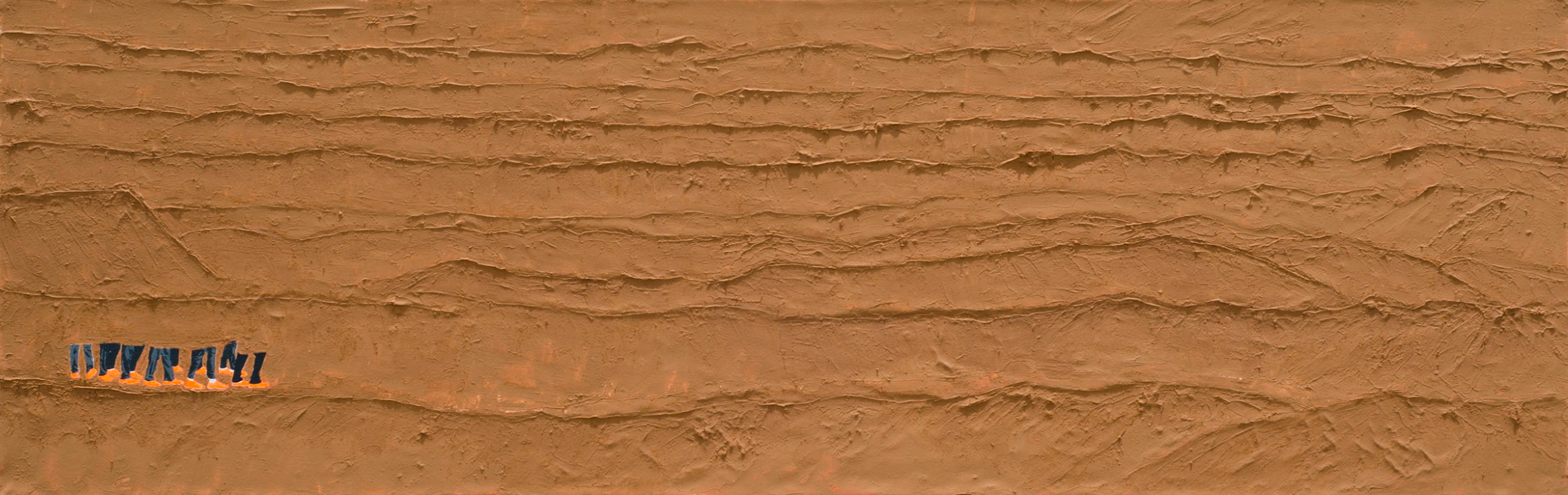

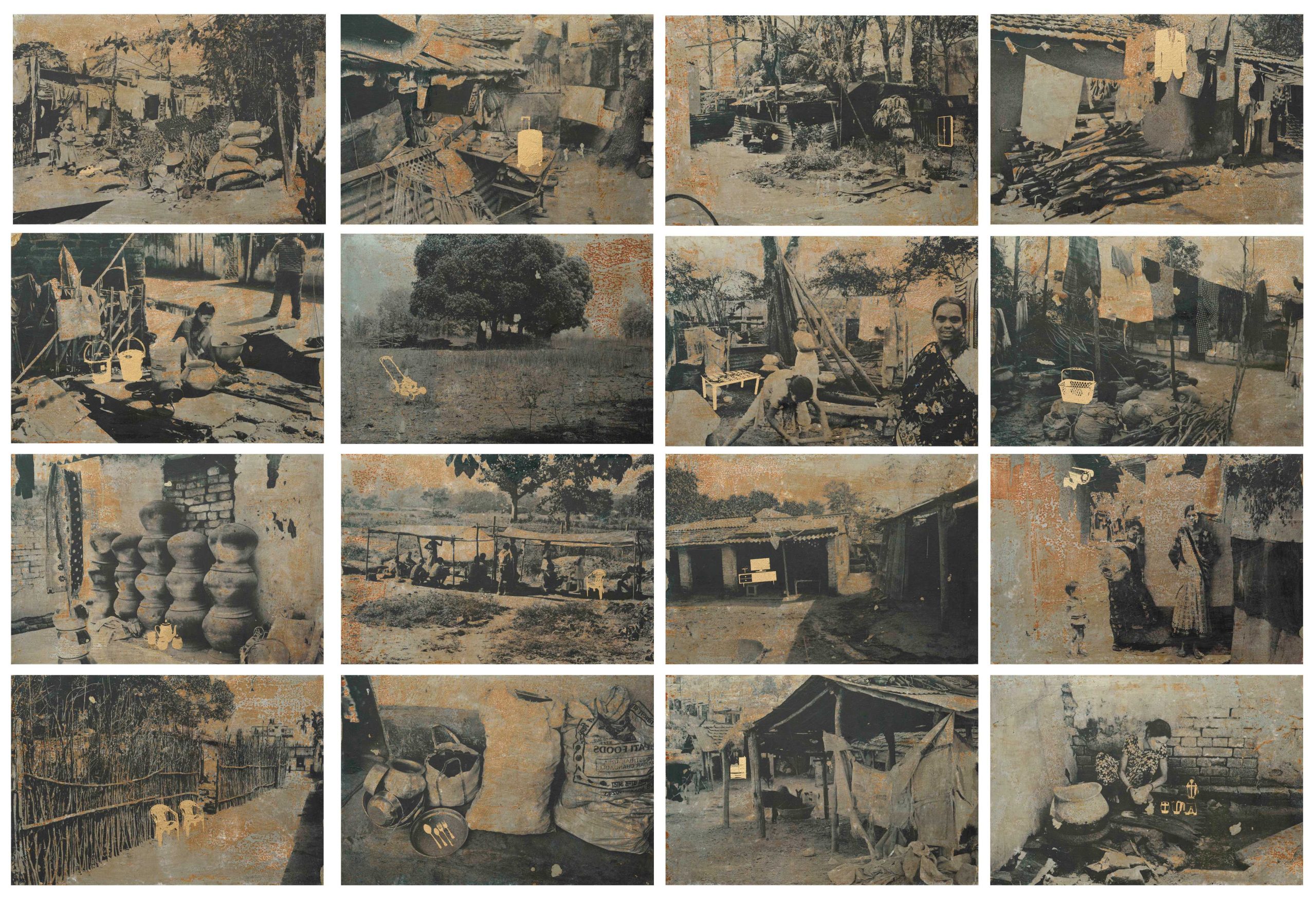

There is an anthropological pulse to Maity’s process: testimonies are methodically indexed into an archive that not only documents, but also re-envisions an epistemic framework capable of accommodating otherwise overlooked subaltern narratives. In They are Looking For a New Village (2022), made using serigraphy printing and soil applied impasto onto canvas, groups of people appear dispersed against a desolate expanse of land. The ochre-yellow laterite soil — sourced from her fieldwork in the villages of Keonjhar, Belpahari, and Jhargram — lends a political contiguity to the work, while the imagery of relocation hints at mass displacement in the area. Made in the years following the Covid-19 pandemic, it is interesting to also think about Maity’s imagination oscillating between the country’s urban metropolis and its peripheries — a condition tied as much to economic necessity as to a slow attrition of identities. The latter, perhaps, finds sharper resonance in an earlier work, When They do not Dance (2018), where she depicts only the uniform-clad legs of mine workers, suggesting a form of assimilation that both dispossesses Adivasis of their cultural distinctness, while homogenising them within an industrial workforce.

The textural depth and multiplicity of applications afforded by serigraphy make it one of Maity’s preferred techniques, which she applies across metal plates, paper, and canvas. Series of smaller-sized works like Portraits from Different Land (2019), Untitled (2021), and Introduction of a Different Way (2019), are clearer and concise, as they limn an intimate portrait of people’s daily routines. They are especially attuned to the tensions and complexities that arise with the acceptance of modernity as labour gets mechanised, and older ways of living grow obsolete. The inherent violence of being “othered”, encoded within these encounters, does not go unnoticed, and is inscribed in works such as When They Stopped Dancing (2018) and How They Looked At Us (2021). Elsewhere, in Wall of Traditions (2021) and sculptures like Dysfunctional Tools (2022), she chronicles baskets, drums, air-dried corncobs, pots, harvest straws, and agricultural tools with an attentiveness that foregrounds endangered customs and knowledge systems not as romanticised relics, but as critical counterpoints that lay bare the promises and failures of “development.”

Although trained as a print-maker, there is merit in situating Maity’s choice and treatment of metals like iron, copper, and brass both within the history of sculpture-making, and also, within the region’s indigenous craft traditions like Dokra (lost-wax casting), to understand how she frames the social ecology of minerals, alongside considering divisions between ‘high art’ and ‘craft’. In Untitled (2022), she props up brass figurines of mining equipment, and worker safety gears like helmets, vests and boots onto paintings of traditional architecture features like the chabutra and wooden chaukhat. Similarly, in her series, In a Span of 15 Years (2023), brass airbricks symbolically bridge transitions between homes made of mud to those of concrete. Through such frequent material juxtapositions, Maity is able to promptly interlink people’s labour and land — the terms and conditions to which are regularly negotiated under a neo-colonial, capitalist order.

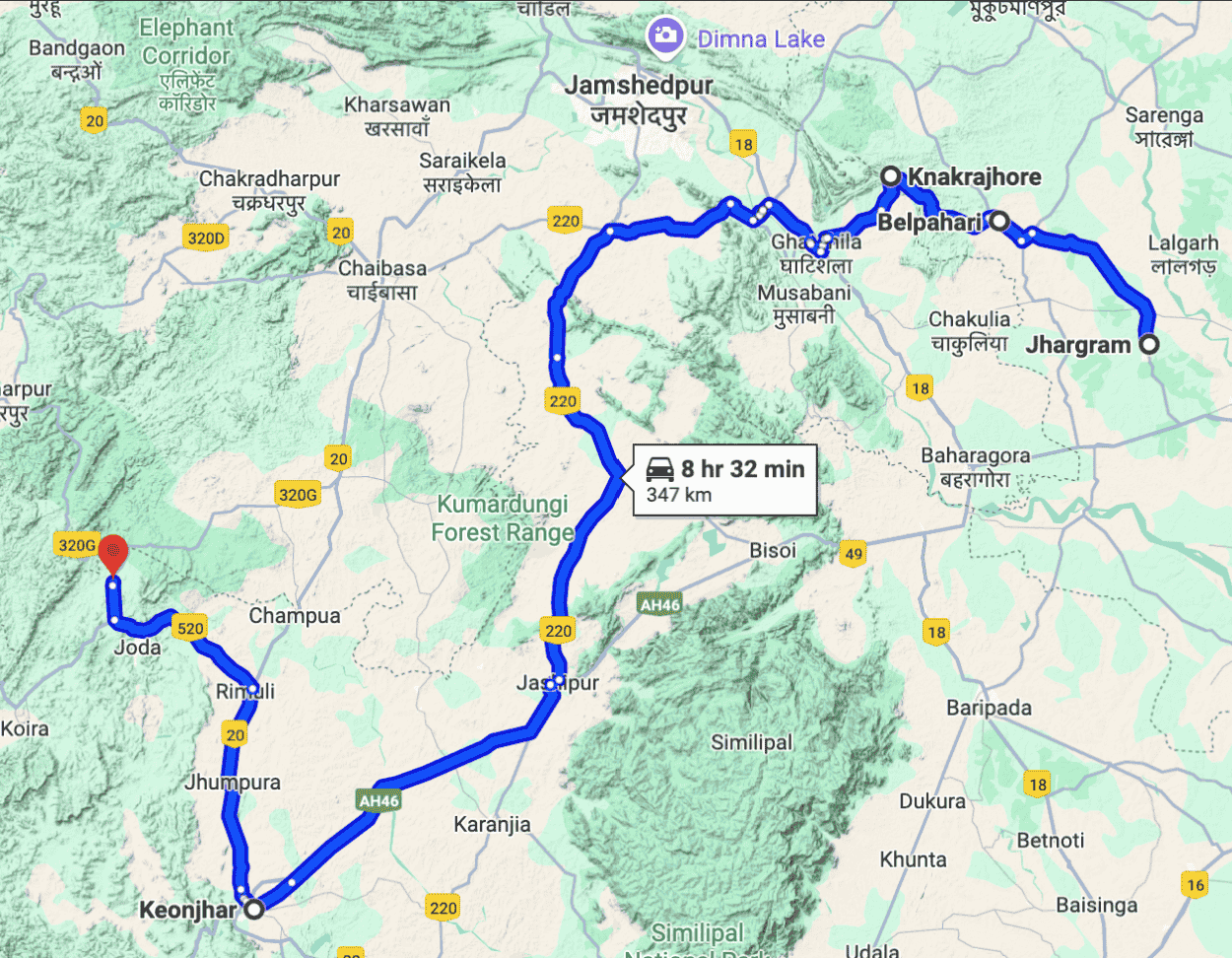

During one of my conversations with Maity, I impulsively tried mapping the names of villages online to trace her travels from the Jhargram district in West Bengal to as far as Kendujhar in Odisha. We spoke about the everyday livelihoods of the Santhal, Munda, and Lodha tribes; about Sonajhuri, Mahua and Sal tree plantations; and from Tarfeni river Barrage, and the Damodar Valley Corporation, to annual cropping, and immigration patterns in Belpahari. She explained how hydroelectricity and iron-ore mining projects have not only displaced Adivasis from their lands, but also depleted groundwater, eroded forests, and caused recurrent floods by altering the river’s course. At the same time, protests against forced land acquisitions, non-consensual relocations, and human trafficking have rarely drawn the attention of mainstream media, while public opinion remains dismissive — often reducing Adivasi struggles to Naxalite-Maoist extremism.2 One only has to look back at the Singur-Nandigram-Lalgarh violence between 2007 and 2009,3 or the starvation deaths among the Sabar tribe community in Amlasol in 2004,4 to understand the extent of bureaucratic mismanagement, state-sponsored human-rights abuse, and police brutality in the region.5

In the preface to The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India, interdisciplinary scholar Rahul Ranjan emphasises upon “writing from a place of solidarity… as a submission to learn and listen to Adivasis; to be able to speak with, not for, them; and to be able to write alongside, not on, them.”6 I believe Maity poses a similar “alongsidedness” through her practice: a way of being with and returning to a people, whose histories, landscapes, and resilience synthesise into her own modes of making and remembering.

- ‘(Un)Layering the future past of South Asia: Young artists’ voices’ curated by Salima Hashmi and Manmeet K. Walia. 11 April 2025 to 21 June 2025 at the SOAS Gallery, London. The work on display was titled Changing the Course of the River (2024).

- A 2015 study published by Bagaicha Research Team on alleged “Naxalite” undertrials in Jharkhand revealed how large numbers of Adivasis, Dalit and other backward castes were caught in false police cases. Most of those who were accused as being Maoists or ‘helpers of Maoists’ were arrested, and imprisoned based on misinformation. Other findings also included a large number of fake cases under the 17 CLA Act, UAPA, and the anti-state sections of the IPC. See Antony Puthumattathil SJ, Marianus Minj SJ, Renny Abraham SJ, Stan Swamy SJ, Xavier Soreng SJ, Sudhir Tirkey, Damodar Turi, and Jitan Marandi, Deprived of Rights Over Natural Resources, Impoverished Adivasis Get Prison: A Study of Undertrials in Jharkhand (Ranchi: Catholic Press Ranchi, 2016), https://sanhati.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Undertrials.in_.Jharkhand.pdf.

- See Santosh Rana, “Lalgarh: A People’s Uprising Subverted by the Ultra-Leftists”, Revolutionary Democracy, July-September 2009. https://revolutionarydemocracy.org/rdv15/lalgarhnew.html. Also see Sumit Sarkar and Tanika Sarkar, “Notes on a Dying People”, Economic and Political Weekly 44, no. 26/27 (2009): 10–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40279767. A consolidated archive of fact-finding reports, and overviews on Lalgarh, Nandigram and Singur is also available on the Sanhati website. https://sanhati.com/excerpted/1083/

- Olivier Rubin, “The Politics of Starvation Deaths in West Bengal: Evidence from the Village of Amlashol,” Journal of South Asian Development 6, no. 1 (2011): 43–65, https://doi.org/10.1177/097317411100600103

- For a detailed overview, see a collection of short-essays and texts in Fr. Stan Swamy, “Adivasi Resistance to Mining and Displacement: Reflections from Jharkhand” (updated April 20 2015), Sanhati, March 10 2015, https://sanhati.com/excerpted/12884/

- Rahul Ranjan, The Political Life of Memory: Birsa Munda in Contemporary India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), xx

Bio

Satyam Yadav (he/him) is an independent arts researcher and curator based out of New Delhi. He is interested in questions of the political economy, contemporary arts, and visual cultures of health, labour and sexuality in relation to wider bio-political histories of South Asia. He has worked as a writer and researcher with several art institutions and universities in India, alongside working with artists. Recent curatorial projects include akâmi- at the Camden Art Centre, London, 2025; Lateral B(l)inds at the India Art Fair YCP, New Delhi, 2024; Natura Urbana, at the Academy of Fine Arts and Literature with Ether Project, New Delhi, 2023; Ways of Our Lives, Somaiya Vidyavihar University, Mumbai 2023, and Embodied Encounters, at the Ram Chhatpur Shilp Nyas with Ether Project, Varanasi, 2022. He was the 2024-25 curatorial fellow at New Curators, London, and the recipient of IMMERSE curatorial residency, Mumbai, 2022-23. He is also a student on partial scholarship in Art and Curatorial Practice at the New Centre for Research and Practice. Satyam holds a MA in Gender Studies from Ambedkar University Delhi, and a BA (Hons.) in History from Ramjas College, University of Delhi. He currently works with the Prameya Art Foundation (PRAF), New Delhi.