THE CURIOUS TRACES OF MASSAGE PARLOURS IN KOLKATA

AUTHOR

Santasil Mallik

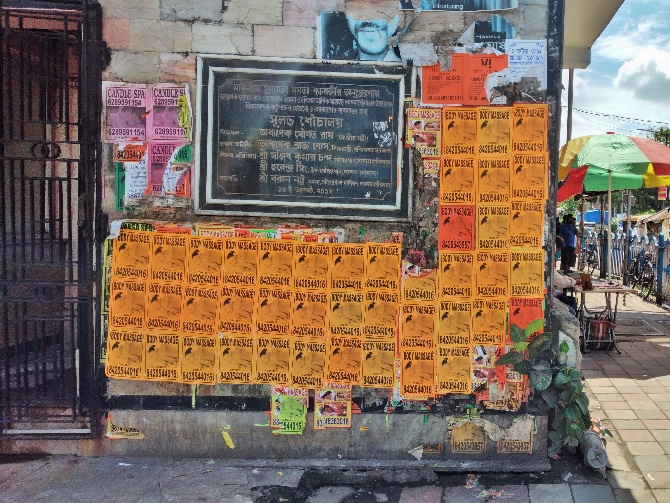

In the streets and by-lanes of Kolkata, it is not difficult to register the ubiquitous presence of posters advertising massage parlours and “relaxation services” across the city. Printed in low-cost tinted papers with stock photographs of spa activities and contact numbers written in bold, they possess a unique visual currency. Usually, these prints appear clustered on walls, electricity boxes, or lampposts, marking an all too familiar break amid the corpus of corporate marketing. From the elite quarters of the city to shanty settlements, they connote particular conduits of consumption that often borders the illicit. But, notwithstanding the air of stigma and suspicion that sticks to the referents of these posters, their circulation suggests a unique landscape of desire in public visual modernity.

The recent spate of police clampdowns upon these enterprises has bolstered the image of parlours honey trapping customers under the pretext of massage services. From 2017 to 2020, the Kolkata Police conducted more than twenty raids, leading to the closure of many spas at shopping malls and streetways. In this recurring local news sensation, colloquially referred to as madhu chakra[1], spa managers get charged for human trafficking and sex workers are supposedly “rescued” by the authorities.[2] The occasional involvement of politicians or actors in these ‘sex rackets’ further spices up the news hour. Likewise, online discussion forums are replete with speculations and conspiracy theories, where anonymous users share different versions of a run-down narrative about getting deceived after following the posters.

It, however, does not go unacknowledged that massage parlours often provide fluid employment channels to many contractual or “flying” sex workers who function in a relatively upscale market or through informal networks of escort services.[3] Interestingly, despite the enterprises’ vilified status by law and general perception, their posters are hyper-visible in the public space. It betrays the furtive covenants involving police authorities, a rupture of whose conditions potentially lead to such violent clampdowns. The peculiar aesthetic field of these paper prints, therefore, operates in the slippery regions between the visible and the conspiratorial, the upmarket and the profane, or the licit and the illicit.

In his book Passionate Modernity, sociologist Sanjay Srivastava coins the term “footpath pornography” while studying the form, content, and spatial distribution of cheaply produced pornography booklets sold in the streets of Delhi. He situates these print productions in conjunction with “other vernacular print cultures where sexuality is a consistent and well elaborate topic of discussion”, including posters of unauthorised sex-clinics or sexual advice leaflets.[4] The advertisements of spas and massage parlours in concern further expand the scope of this category. Here, sexuality is not a direct point of address but gets closely implicated by the associations these prints have developed in civil society. They share similarly (un)structured communication networks, reflecting the “erratic signs of illicit economies of the city.”[5] Their advertising rationale corresponds to subterranean markets that work around a distinct regime of public cognisance.

These “footpath” print cultures, navigating sexuality and sexual services, activate a disjointed viewing experience befitting the rhythm of street commutation. [6] Most of the massage parlour posters are site-specific, concentrated in and around locales where the establishments are based. The clientele distribution map, therefore, largely depends on commuters’ acquaintance with the particular city quarter. In localities with several establishments, familiar posters compete over unratified spaces to form multiple strata of arresting collages. Such competitive sites invite a unanimous field of response due to the prints’ formal homogeneity. Instead of an individual poster, multi-layered collage sites become the locus of attention. Nonetheless, any overarching propositions about the posters’ visual coordinates are subject to contestation, given the unstable business and promotion models they manoeuvre.

While the advertisements appear attuned to male heteronormative expectations, massage parlours proffer ambiguous forms of sexual communication that are usually premised on secrecy and dubiety rather than necessarily nonconformist sexual motives.[7] They are also potent avenues for male commercial sex workers, many of whom have had unintentional beginnings in the parlours before becoming attuned to the trade. Kunal Basu’s novel, Kalkatta, precisely uses this context as the narrative’s background where Jamshed Alam, a second-generation Muslim migrant, takes up sex work in an elite escort service masked behind the façade of a massage parlour.[8] Written in Alam’s voice, the novel infuses predictable themes of adultery, sexual exploitation, migrant crisis, terrorism, and the black market economy in a heady mix, underscoring all the anxieties that inform these spaces. It is easily discernible that the visibility of massage parlour posters in the city builds upon the subtextual discourses of pleasure and illegality.

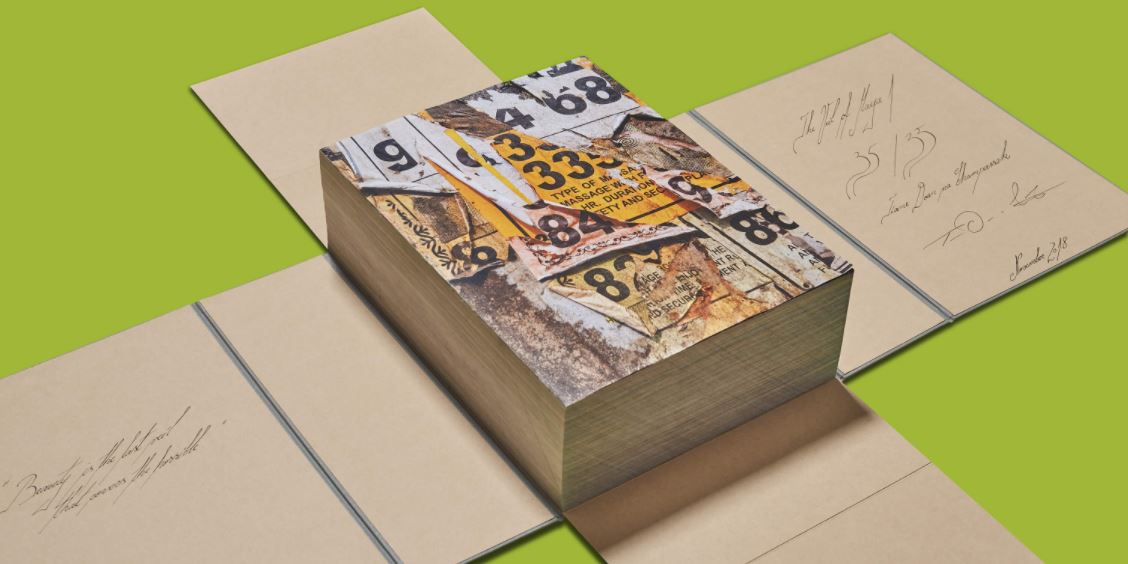

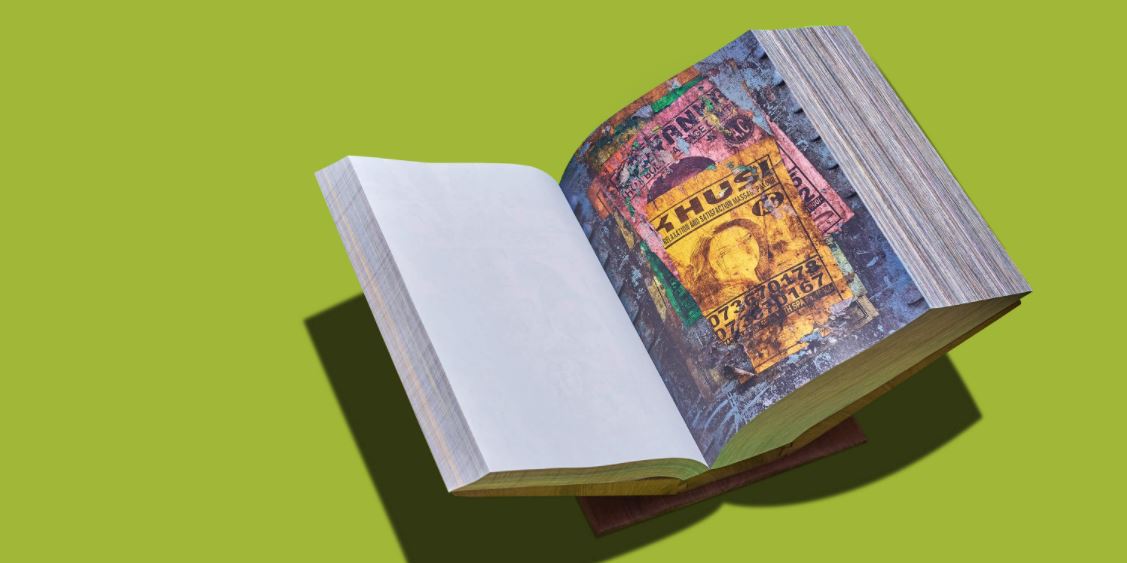

In the limited-edition photography book, The Veil of Maya I, French artist Tiane Doan Champassak conceives the signification of this print culture in Kolkata from an altogether different, spiritual-allegorical perspective. It is the first publication from his ongoing, seven-part The Veil of Maya series which deals with the idea of “the duality of enchantment-disenchantment.”[9] In January 2018, he photographed layers and traces of these colourful posters that clung to the walls like “an aesthetic bacteria”[10] and incited mixed feelings of attraction and repulsion in him. More than the representative values of the ads, the work engages with the materiality of the print collages. The cheap texture of the posters – “the flayed skin of the city”[11] – becomes a surface to play out the tensions between promise and fulfilment in the metropolis.

Champassak’s book project strives towards “an editorial ideal of copiousness”, worth 2000 pages, whose goal is “to have the viewers flip through pages of the book as if they were touching the walls of Kolkata.”[12] Shot in less than four days, his “photo marathon” enunciates the collages as “city palimpsests.”[13] It strongly resonates with this print culture that resides in Kolkata’s subliminal visual consciousness. In tatters and unformed juxtapositions, the paper flakes of promises project a map of pedestrian desires and parallel economies. The semantics and contextual meanings of the posters exist in conversation with the textural surfaces of the print layers and their street spatiality. As a result, anyone traversing this inconstant landscape cannot help but be animated by ingenious patterns, collages, and accidental aesthetic formations lurking around the next street corner.

Notes

[1] Honey trap inside Spa centre at Kasba in kolkata, seven arrested (sangbadpratidin.in)

[2] 29 Sex Workers Rescued from Spa, Saloon in Kolkata; 30 Including Brothel Managers Held (news18.com)

[3] Dasgupta, Satarupa. “Commercial Sex Work in Calcutta: Past and Present”, Selling Sex in the City: A Global History of Prostitution, 1600s-2000s, Brill, 23rd August2017, p. 519

[4]Srivastava, Sanjay. Passionate Modernity: Sexuality, Class, and Consumption in India, Routledge, 2007, p. 167

[5] Srivastava, Sanjay. Passionate Modernity: Sexuality, Class, and Consumption in India, Routledge, 2007, p. 167.

[6] Srivastava, Sanjay. Passionate Modernity: Sexuality, Class, and Consumption in India, Routledge, 2007, p. 175

[7]Boyce, Paul and Akshay Khanna. “Rights and representations: querying the male-to-male sexual subject in India”, Culture, Health, and Sexuality, Vol. 13, No. 1, 2011. p. 95.

[8] Basu, Kunal. Kalkatta, Pan McMillan India, 2015

[9] The Veil of Maya 1 – Tiane Doan Na Champassak (THE VEIL OF MAYA 1 on Vimeo)

[10] The Veil of Maya 1 – Tiane Doan Na Champassak

[11] The Veil of Maya 1 – Tiane Doan Na Champassak.

[12] In an email interview with the author

[13]In an email interview with the author

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Santasil Mallik is a visual artist and researcher currently pursuing his M.Phil from the Centre for English Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. His research focuses on the intersections of literary and visual cultures in the modern political history of Bengal. As a practitioner, he is interested in exploring formalist, non-narrative approaches to filmmaking and photography. His works have been exhibited at several spaces across Switzerland, Italy, Columbia, Germany, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and other countries.