The Social Life of Food in Indian Cinema

AUTHOR

Shirin Mehrotra

In The Lunchbox (Dir: Ritesh Batra), a 2013 Hindi film about an epistolary romance in Mumbai, a series of montages shows the lead character Ila cooking a host of dishes. Not for her husband, but for a man called Sajan Fernandes who she only knows through letters exchanged via wrongly delivered dabbas meant for her husband. In cooking, Ila finds refuge from her loveless marriage and from a husband who doesn’t even notice that he’s been delivered the wrong lunch. The shots of her dexterous hands tying a thread around a stuffed bitter gourd and shaping soft paneer into kofta, show the love and precision in her cooking.

In contrast, the cooking montages in the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen (Dir: Jeo Baby, 2021) convey the monotony pervading the life of an Indian housewife whose day revolves around cooking for and cleaning after the men in the family. Cooking in this film doesn’t exude love: it highlights systems of oppression precipitating in frustration and simmering anger.

For the most part, food has not played an active role in the narratives of Indian cinema. And on the off chance that it features in a film, it is used to show a woman’s dedication towards her family or the man she’s in love with. However, in recent times, filmmakers are conversing more through the act of cooking and eating. Films across Indian languages now weave in aspects of liberation, caste discrimination, desire, and power into the narrative, and they do it through food.

The politics of a domestic kitchen

Our cultural conditioning has led us to believe that the kitchen is a woman’s domain. Often in Hindi cinema, cooking has been used as a way to show the taming of a shrew – a once-‘modern’ girl running out of a kitchen wearing a saree is a popular narrative; remember Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Bawarchi (1972)? The domestic kitchen is then portrayed, with a certain nostalgia, as a gendered space.

Neeraj Ghaywan’s Hindi film Juice (2017) breaks that nostalgic lens. The short is set in a middle-class home in small-town India. A get together is on – men sitting and chatting comfortably in the living room in front of an air cooler, drinks in hand, while women huddle around the hot and humid kitchen, making dinner. It’s a scene right out of the life of most upper-caste, middle-income Indian families. The film doesn’t just focus on the gendered division of household labour – the men crack casual sexist jokes, show their support towards right wing politics, and, in a scene where one of the women guests pulls out a steel glass to pour chai for the domestic worker, Ghaywan highlights the everyday casteism that is rampant in Indian homes.

In Chaitanya Tamhane’s Marathi film Court (2015), a scene from the domestic life of the public prosecutor subtly illustrates the experiences of a working woman expected to juggle her professional and personal life without much help. Both husband and wife work a nine-to-five job. But the husband comes home and sits in front of the television, while the wife changes, freshens up, and heads straight to the kitchen. The rest of her evening is spent there, cooking dinner for the family. But unlike Court, Juice ends with an act of defiance. Manju, the woman of the house, picks up a chair and drags it to the living room, placing it right in front of the air cooler. She sits down, aware of the discomfort this act of hers has caused the men, and drinks from her glass of orange juice.

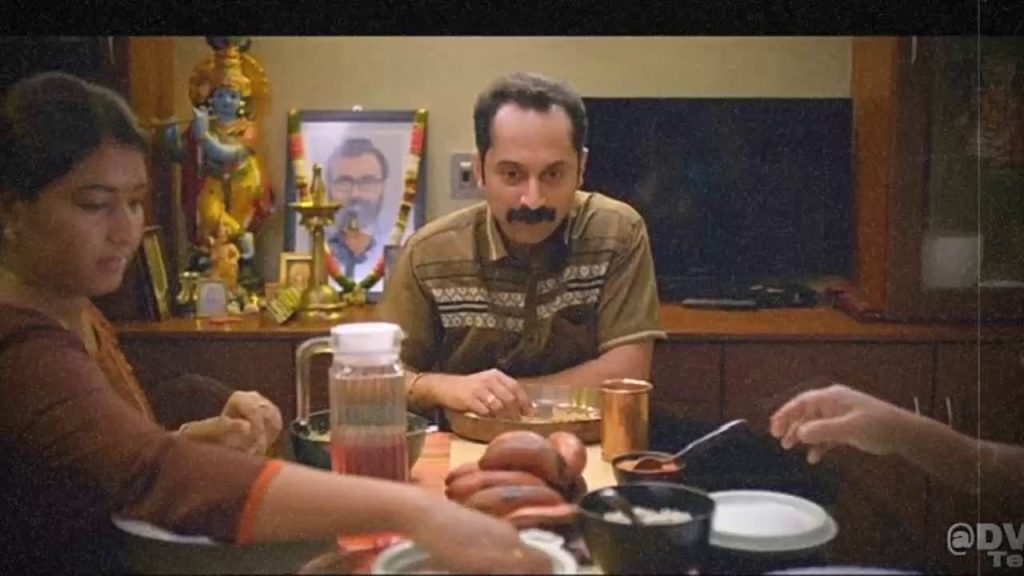

As opposed to the films exploring the relationship between food and gender by looking at the oppression of women in domestic kitchens, the Malayalam film Kumbalangi Nights (Dir: Madhu C. Narayanan, 2019) portrays the performance of masculinity in relation with food. Shammi, who shares the house with his newly-wedded wife, her sister, and mother, assumes the position of the family patriarch; he subtly moves his chair to the head of the dining table as he invites the rest of the family to sit and eat around him. He’s a ‘man’s man’ and in his world, women are mere second-class citizens. In total contrast, Saji who has shared a dysfunctional relationship with his half-brothers so far, cooks and shares meals with his real as well as adoptive family (his dead friend’s wife and his half-brother’s girlfriend) and assumes the position of nurturer as he begins to let himself be vulnerable. The film shows two forms of familial commensality, one authoritarian and the other egalitarian, both mediated through dining practices.

Cooking can often be an act of vulnerability. In a poignant animated Bengali short Maacher Jhol (Dir: Abhishek Verma, 2017), a young man decides to come out to his father by making him his favourite Bengali-style fish curry – a need for acceptance wrapped in an act of care.

Prejudiced foods and caste politics

Where popular Hindi cinema has shied away from conversations around caste, regional films have been more vocal and have used the cultural significations of food to bolster the narrative. In Malayalam director Lijo Jose Pellisery’s films, meat becomes the main character. Both pork (Angamaly Diaries, 2017) and beef (Jallikattu, 2019) are taboo meats for upper-caste Hindus and an important part of the diets of the lower castes. These meats are also intrinsic to Kerala’s food culture and, by making them part of the main narrative, Pellissery asserts the notion of India as a meat-eating country, against Brahmanical projections of ‘purity’ and vegetarianism.

In the Tamil feature Koozhangal (2012) director PS Vinothraj goes a step further to showcase the relationship between extreme marginalisation and food. In this visually captivating film, we see a family living on the peripheries of society, feeding on rats that they skilfully capture and roast live on fire. And we see Ghaywan’s depiction of everyday casteism – separate utensils for Dalit and lower caste guests – once again in his recent Hindi short film Geeli Pucchi (2021).

In the Hindi/English film Axone (Dir: Nicholas Kharkongor, 2019) we see the ways in which the mainland others the food eaten by adivasi communities in India. Axone (pronounced akhuni), a staple food of the North East, has been a major reason for conflict in student accommodations and residential areas in Delhi where a large number of North-Eastern migrants reside. The fermented soybean paste, when cooked with pork, produces a thick aroma, causing much prejudice around the dish and the food of the region at large. The film highlights this prejudice through the story of a group of migrants living in Delhi’s Humayunpur area. There’s an overt burden of shame and guilt that the protagonist experiences as she attempts to make axone for her friend’s wedding ceremony. A similar emotion is captured in Kaaka Muttai (Dir: M. Manikandan, 2015) where the mother is ashamed because her sons eat crow eggs stolen from the bird’s nest: coming from extreme poverty, the kids do not have access to chicken eggs and rely on kaaka muttai (crow eggs) to “get stronger”.

Dishing desire

Food for long has been a vehicle for expressing desire, whether through the written word or the visual medium. But in Hindi films, food has largely been used as a metaphor to sexualise the female body in “item songs” – main toh tandoori murgi hoon yaar gatka le saiyan alcohol se in Dabangg 2, hai hai mirchi in Biwi No. 1, to name two instances. Rarely has a film deployed food as part of the main narrative to explore desire. The Assamese film Aamis (Dir: Bhaskar Hazarika, 2019) does exactly this and stretches the inquiry to darker lengths. A young food anthropologist (Sumon) and a married doctor (Nirmali) find intimacy through shared meals. As their meals get more adventurous and exotic – from rabbits to bats to human flesh – their intimacy grows, blurring the line between pleasure and pain, two sides to the same coin. In 1991, Satyajit Ray explored the idea of cannibalism through a conversation in his film Agantuk. Manmohan Mitra, a wanderer, who is visiting his niece after decades, says that he’s heard about human flesh being tasty but hasn’t had the good fortune of tasting it. Hazarika’s Nirmali then completes the unsatiated hunger of Ray’s character.

From using food to portray economic inequality in a newly independent India – think Do Bigha Zamin (1953) or Roti (1974) – to painting the kitchen in nostalgic shades that bolster the constructs of a ‘good wife’ and an ‘ideal family’ – Bawarchi, Hum Saath-Saath Hain (1999) – to now exploring the modalities of gender, caste, identity and desire, popular Indian cinema has come a long way. And while we’re far from making a Tampopo (1985), where food acts as a core device enabling the interrogation of multiple themes, this is still a big leap that bodes well for the future of Indian filmmaking.

About the Author

Shirin Mehrotra is a food writer, researcher, and anthropologist from India. She writes about the intersection of food, society, culture, and cities and their foodscapes. Her work has been published in Whetstone, The Juggernaut, Conde Nast Traveller, Nat Geo Traveller, Roads & Kingdoms, Feminist Food Journal, HT Brunch, Indian Express, and The Hindu, among others.