Tracing the history of Print: The case of Atelier Prati

Author

Sumitra

Printed materials like pamphlets, paper packaging and newsletters, which invoke a sense of nostalgia, are also deeply connected to regional and vernacular histories. For the past two centuries, this form was used both as a tool for dissemination of political messages and significantly for Modern Art, as both artistic and promotional medium. Print is also an important element in the ephemera of the protest site. Saidiya Hartman[1] and Jose Esteban Munoz[2] speak of ephemera as essential to the archive. The work of these two scholars will help understand the significance of print to regional stories. This essay will pick up on Okwui Enwezor’s lament on the archive and will use thinking about ephemera to unpack the significance of a single printmaking studio in Bangalore: Atelier Prati, a new addition to the collective art practice story in Bangalore, where industrial age printing presses are restored and used.

‘Photographers and printmakers, it seems, have gone back to historic processes

to turn their negatives into positives’ (Joshua Muyiwa 2021)[3]

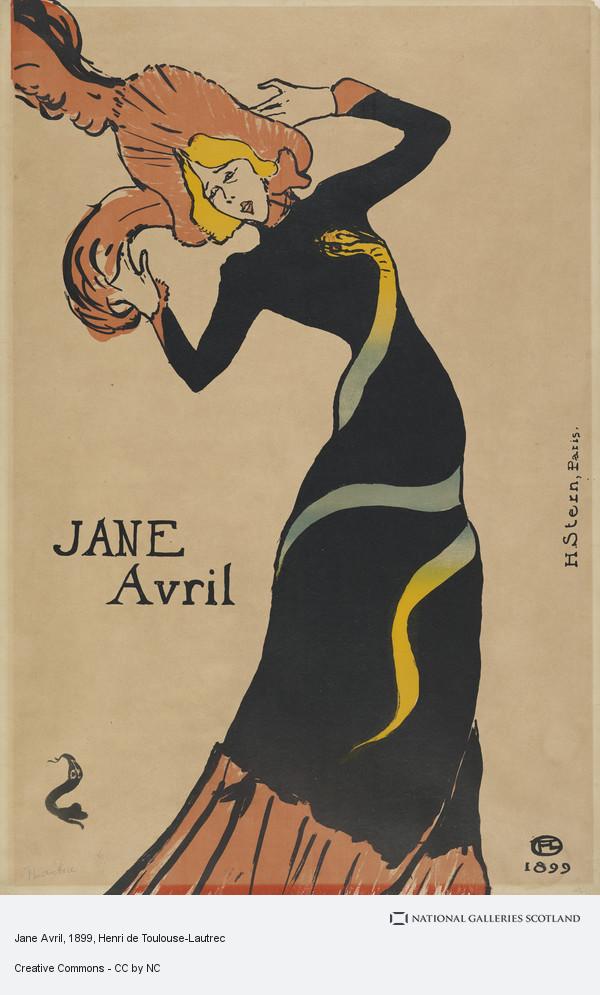

The story of Atelier Prati begins with Jayasimha Chandrashekhar, who has been envisioning a space for printmaking in Bangalore since he graduated from the College of Fine Arts in 2017. In the history of art practice since 2000, printmaking has been relegated to ‘optional’ coursework and studio hours in major art schools in the country. At one point, a most useful and sought-after specialisation, printmaking’s history is tied very closely with the emergence of popular media[4]. It was a core utility during resistance movements. The technology of printing presses entered the Indian subcontinent in the sixteenth century followed by the establishment of printing presses soon after. Material that can be archived includes pamphlets, gazettes, newspapers, chromolithographs to name a few. Calcutta of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a public quickly cottoning on to weeklies like Hicky’s Bengal Gazette (1780) and The Asiatic Mirror[5] (1788). By 1761, cities in Southern India like Madras (now Chennai) have been recorded as publishing the most English content in South Asia. There is of course the facet of Fine-Art printmaking like the work of the French illustrator Henri De Toulouse Lautrec, as well as Katsushika Hokusai, the Japanese master of woodcut printing.

Prati, the Atelier is new. Bangalore has an eclectic mix of practices and in this setting, the emergence of a space that is dedicated to older printmaking methods addressed a lacuna. Digital options are easily accessible and the art of creating work on a litho[6] block or carving wood to create a composition had almost disappeared. Even in the textile industry, block printing studios that were popular in the 70s and 80s have now dwindled in numbers. Jayasimha, along with some colleagues and S Basavachar have built this to be both a studio for artistic practices and a space that designs and conserves manual printing presses. They have found and restored two nineteenth century lithographic presses, along with around 60 blocks during the short time they have been around. These blocks include the original blocks that were used for making beedi wrappers back in the day.

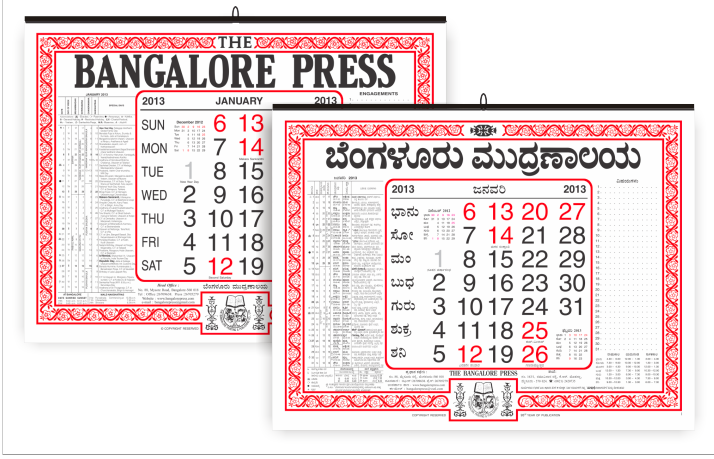

Joshua Muyiwa, in a recent piece speaks about analogue printing in various pockets of the country[7]. They refer to the historic printing processes like darkroom photography and lithography becoming more attractive to artists from this generation, especially in the current climate of a global pandemic. Stepping away from the contemporary movement of renewed interest in this art form—printmaking as a discipline in the visual arts has a very distinct history too. Bangalore’s relationship with printmaking is tied closely with the history of the State of Mysore. For example, Bengaluru Puttaiah, who headed the Mysore State Government Press[8], in the 1920s spent a great part of his career promoting printing technology at the time. He helped the Kannada Sahitya Parishath set up its own printing division as well. Sir M Visvesvaraya (the 19th Diwan of Mysore) set up the Bangalore Press which was the official publisher of the Wadiyar Royal Family. The calendars and Diaries produced by the company continue to be in use in most households.

Jayasimha began his work towards establishing Atelier Prati as a landmark space for printmaking about five years ago. Since then he has been able to work with similar if not allied spaces. In August of 2019, Chatterjee and Lal in Mumbai hosted a show that marked a seminal moment in printmaking. Making a case for printmaking in the visual arts, a 2019 show called The Arthur Bunder Press, Colaba[9] turned the art gallery into a workshop. This kind of show set the tone for the work Prati would do. Since its inception, the atelier has supported the creation of several unique works including a series of etched drawings that speak to the cultural and political implications of the organic world[10] (Hakim, Shah, and Subramaniam 2019). Another show in 2016 – Terra Cognita? reflected on the formative role the print has played in our Postcolonial consciousness[11]. It was an archive installation that celebrated the print.

The name Prati, is derived from the Kannada word for edition. Keeping true to the process of printmaking, the space aspires to renew interest in this form. One of the more ambitious projects that the atelier aspires to do is a detailed survey/documentation of all the ways in which printmaking has contributed to the regional artscape. Jayasimha has used his connections with art schools in the city to establish professional printmaking studios. Srishti School of Art, Design and Technology has benefited from his expertise on letter press printing. This form is not just limited to the visual arts and design. For example, block printing textiles was prolific in the 70s and 80s in the city. Today, there is only one fully functional hand block printing enterprise in the city. The print has a very formative role in our imagination of popular art. From comic to political strips published in the dailies, the sheer volume of material that owes its presence to printmaking is huge. Spaces like Prati are important for the longevity of these forms.

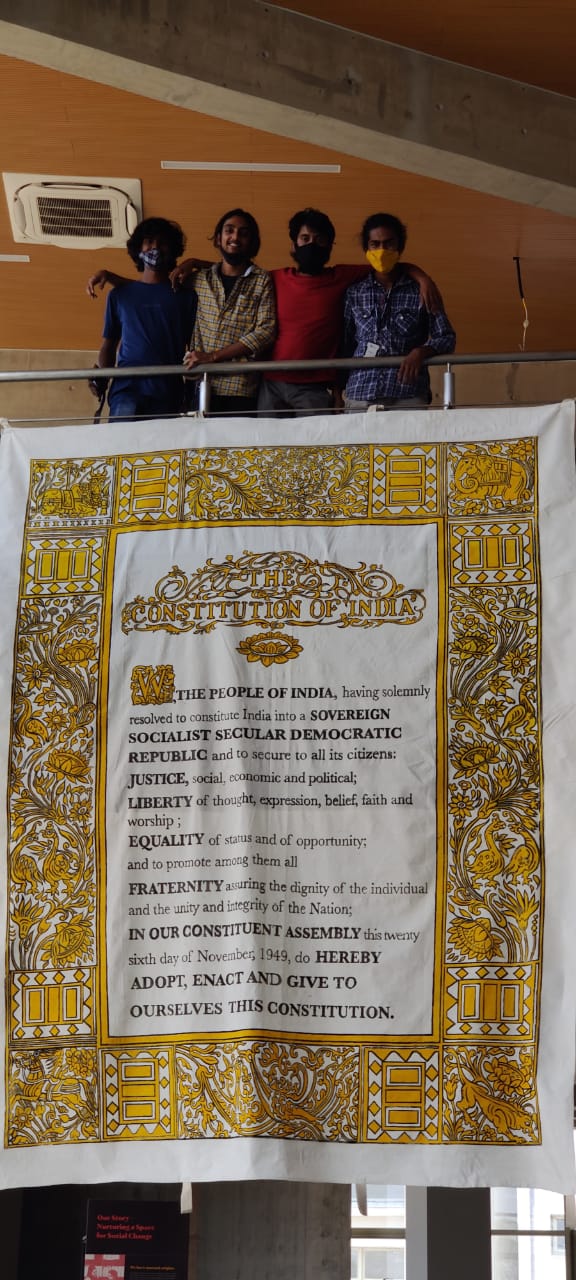

Atelier Prati is the space created for and by the modern printmaker. Of the work that Prati has done since its inception, one worthy mention is the commission by Azim Premji University to create a large format print of the Preamble of the Constitution of India. This project was meant to be a part of the display at the new campus of the University in Bangalore. Jayasimha was very quick to suggest that a large 11 feet by 9 feet plywood could serve as a block to carve the artwork and words. The team took about a month to carve and print the work. This kind of hands-on process clearly distinguishes the work Prati does and will continue doing.

References

1 Hartman, Saidiya Venus In Two Acts – 2008 – Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism, Number 26, Volume 12. Pp. 1-14

2 Munoz, Jose Esteban Ephemera as evidence: Introductory notes to queer acts – 1996 – Women and Performance, Number 8, issue 2. Pp. 5-16

3 Muyiwa, J., 2021. Atelier prati Latest News on Atelier-prati Breaking Stories and Opinion Articles – Firstpost. [online] Firstpost. Available at: https://www.firstpost.com/tag/atelier-prati [Accessed 21 June 2021].

4 Stewart, A. (2013). The Birth of Mass Media: Printmaking in Early Modern Europe. Availableat: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1023&context=artfacpub>

5 Mulholland, J. (2021). Before the raj: Writing early anglophone India. Johns Hopkins University Press.

6 Colour lithography usually requires a separate stone for each colour. The stones must be carefully positioned so that the elements are correctly aligned in the final image. Lautrec’s poster for the dancer Jane Avril employs an innovative process in which three stones are used to print four colours; applying blue and yellow ink together with one roller on a single stone. The broad areas of colour and simple composition reflect his interest in Japanese prints. This is one Lautrec’s final works and is particularly rare

7 Muyiwa, J., 2021. Atelier prati Latest News on Atelier-prati Breaking Stories and Opinion Articles – Firstpost. [online] Firstpost. Available at: https://www.firstpost.com/tag/atelier-prati [Accessed 21 June 2021].

8 Moona, S. (2020, January 2). The pioneer of printing process. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/society/history-and-culture/the-pioneer-of-printing-process/article30459132.ece

9 Gehl, R. (2019, August 14). PRINT RUN. Mumbai Mirror. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/others/things-to-do/print-run/articleshow/70666104.cms.

10 Hakim, Arshad, Moonis Ahmad Shah, and Sarasija Subramaniam. 2019. ‘A Voyage of Seemingly Propulsive Speed and an Apparent Absolute Stillness’. Gallery Ark. Vadodaa: Gallery Ark.

11 Hoskote, Ranjit. 2016. ‘Recapturing Lost History: Key Moments in the Journey of the Graphic Image in India’. Scroll, December 2016.

About the Author

Sumitra is a curator based in Bangalore, India. She is a queer woman and has been involved in the organization and implementation of some initiatives in Bangalore, India. Between 2012 and 2015 she was closely involved with the annual Namma Pride festivities in the city and in 2017, worked closely with a filmmaker T Jayashree to set up the beginnings of QAMRA–a Queer Archive for Memory, reflection and Activism. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Art History (2007) and a Master of Arts degree in Museology (2010). She has also spent 7 years pursuing a doctoral degree in Art History, beginning in 2012. A recipient of multiple awards from the Kochi Biennale Foundation, the Curatorial Intensive South Asia for curatorial work, as well as a 5-year fellowship to pursue doctoral research in Curating Contemporary art, her interests are in archival work and following a rather unorthodox path.