Wait for Weight: Collective Performance as Resistance

AUTHOR

G. Vignesh

In a time of intensifying ecological collapse—when forests are felled in the name of urban development and the rhetoric of “progress” is weaponised to erode habitats—can art embody resistance? Can art not only mourn loss but also actively halt it?

Wait for Weight, a site-responsive performance by the emerging interdisciplinary action group; Possible Futures, rooted in gesture, endurance, and sonic invocation, has emerged as a tender political intervention—a shared act of grief, resistance, and refusal. This essay frames it within broader dialogues in performance studies, eco-activism, and South Asian resistance histories.

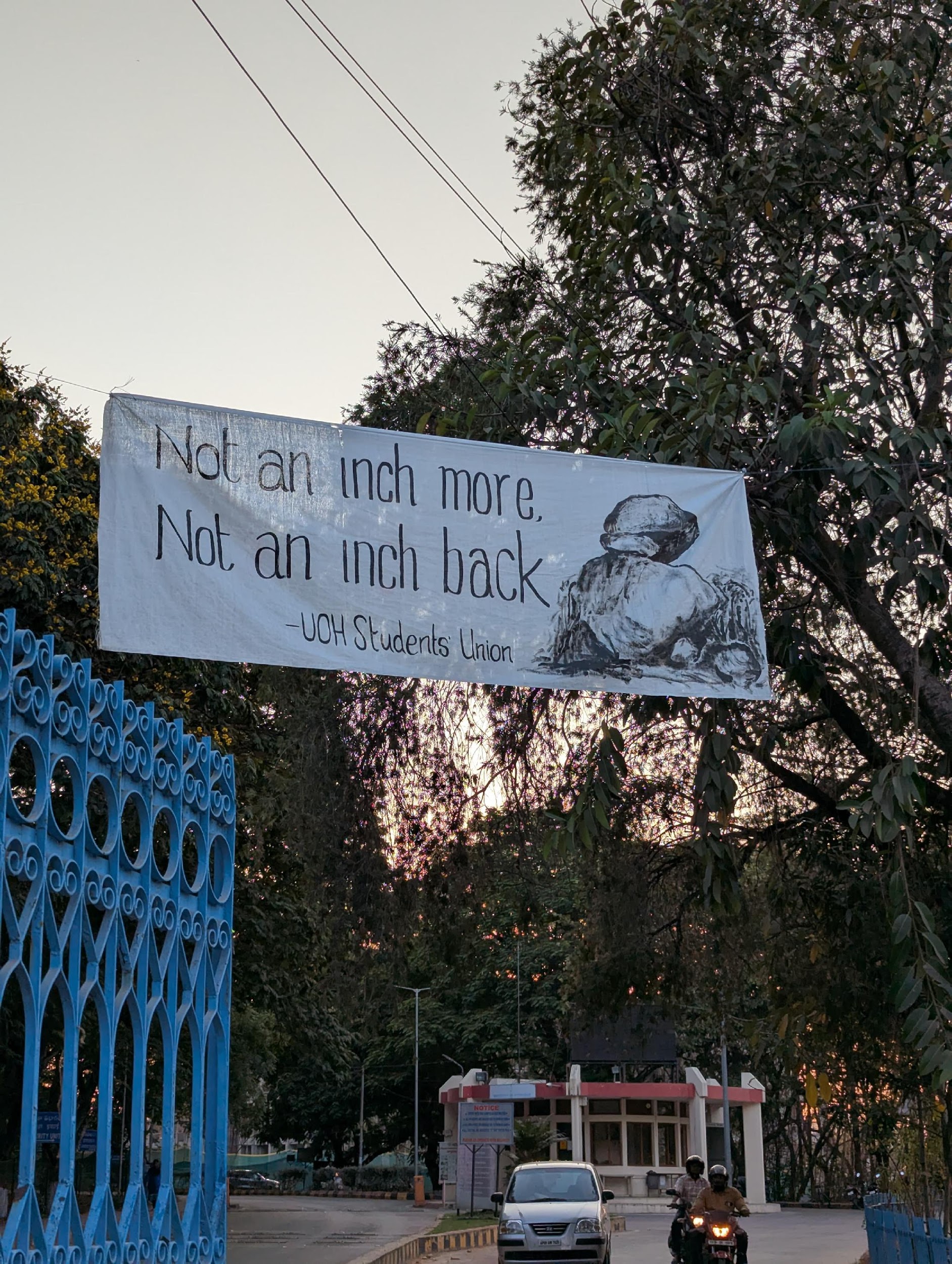

The performance unfolded amid a student-led movement at the University of Hyderabad that successfully halted the auction and deforestation of nearly 400 acres of ecologically significant forest land (see Figure 1). The protests—anchored in solidarity, care, and collective refusal—had already disrupted the narrative of inevitability around ‘development’. Possible Futures chose this moment to create a work that echoed and deepened the call to action. The slogan of the protests—’Hum jungle bachane nikle hain… Aao hamare saath chalo’ (We have come out to save the forest… Come, walk with us)—was not merely a chant, but a living invocation woven into the performance itself.

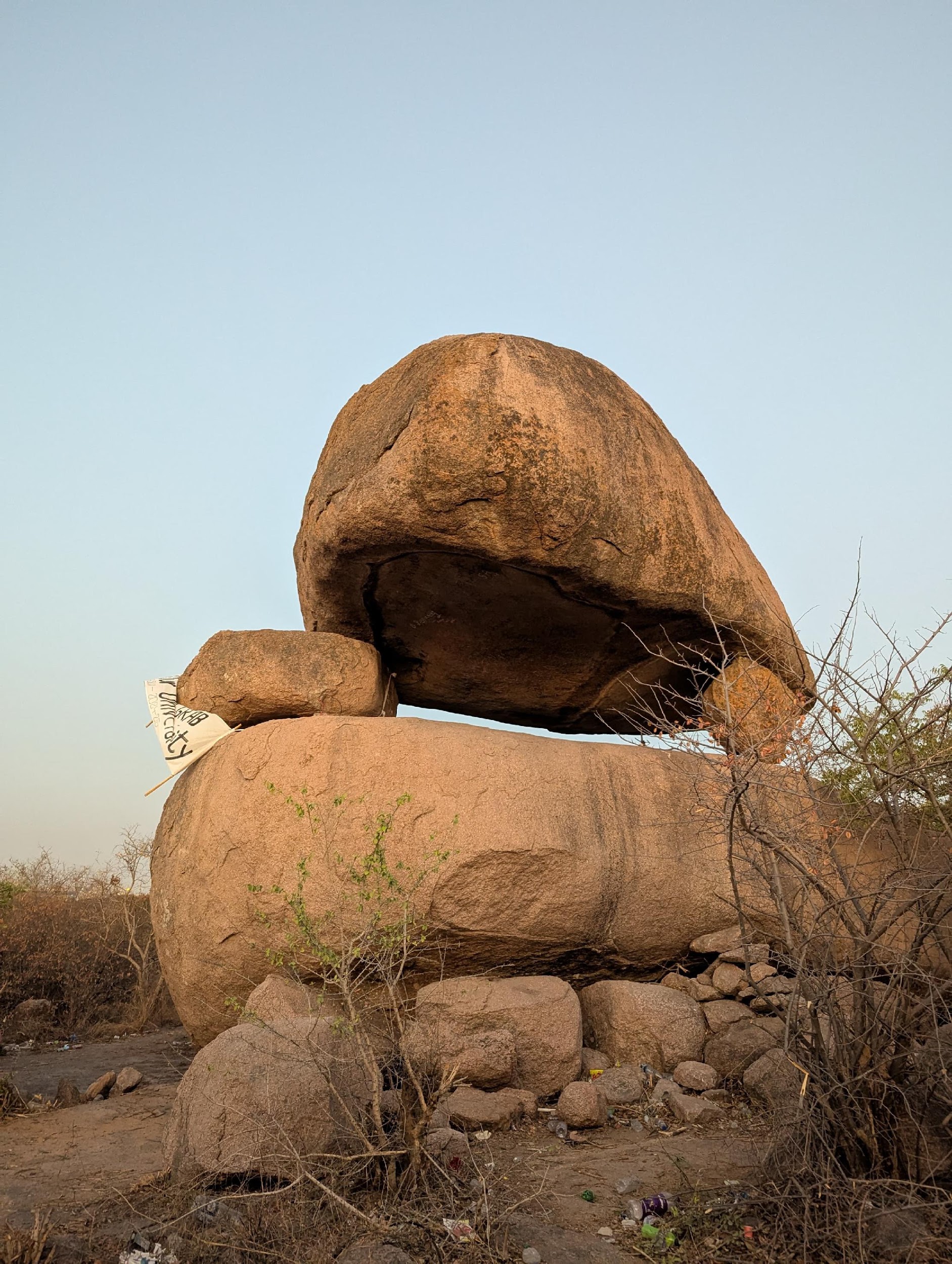

On International Forest Day and the Spring Equinox, Possible Futures gathered at Mushroom Rock—an ancient granite formation and geological icon of the Deccan plateau—as more-than-symbolic ground (see Figure 2).

The date brought together the cosmic and the terrestrial, inviting a ritualistic framework that blurred lines between protest, poetics, and ceremony. Possible Futures—comprising visual artists, theatre practitioners, and students—staged the work not only as witness to ecological grief but also as an embodied continuation of the ongoing resistance.

At Mushroom Rock, the performers invited the site itself into their work. The land, air, and stone became collaborators, framing a dialogue between human and nonhuman presences (see Figure 3). The piece unfolded over an hour, yet its rhythms echoed the slow, patient time of forests and rocks. In this confluence of bodies, material, and sound, the platform asked: what does it mean to carry the weight of preservation? What does resistance feel like—not as ideology alone but as sweat, care, and shared breath?

As Amelia Jones writes, “Performance art demands a reconsideration of presence and embodiment, operating in the space between the material and the ephemeral.” Performance art has long served as a medium for embodied resistance. From the avant-garde confrontations of Dada and Fluxus to Ana Mendieta’s earthworks and Rummana Hussain’s feminist interventions, artists have used the body to speak where words fail. In India, the likes of Inder Salim and Nikhil Chopra have blurred boundaries between identity, endurance, and ecology in site-specific acts.

The central image of the performance was a nest: a giant, hand-woven structure of branches, grass, and roots gathered from the site. This act of making—slow, collaborative, physical—became a living metaphor for refuge, care, and reclamation. The performers enacted distinct yet interconnected gestures of resistance, memory, and care (see Figures 4a–4e): Vignesh traced shadows and imprints of bodies and objects, evoking memory and impermanence. Shivam, shifting between human, bird, and animal, called out with sounds of longing and distress, bridging species. Suresh carried and struck stones until they shattered, conjuring the violence of construction and human labour. Bhanu, wrapped in green construction netting, held a mirror aloft, reflecting and fragmenting the landscape in a quiet question of visibility and erasure. Vishal dragged discarded plastic bottles while singing a Bhojpuri folk song about forests and water, his voice gathering the others into a collective chorus that transcended language and region. Manjari knelt before rocks, whispering to them and arranging them in a quiet ritual of reverence.

At moments, real peacocks—residents of the forest—answered the performers’ calls, merging the boundaries between performer and environment, art and ecology. This “ritual ecology,” as Fern Shaffer and Othello Anderson describe it, attuned the body to threatened landscapes. The nest, fragile yet resilient, stood as a testament to shared participation, responsibility, and the possibility of renewal.

Throughout the performance, Possible Futures resisted the idea of art as detached observation. Instead, they embraced what Paula Serafini describes as “performance action”—a convergence of process-based collective creativity and direct political intervention. In this sense, Wait for Weight was not just a protest performance but also a relational practice that held grief, urgency and hope in equal measure.

As Sonal Khullar notes, “Performance art in India draws from ritual, activism, and public interventions, transforming the body into a site of resistance and renewal.” In this lineage, the performers became both witnesses and agents of change—bearing testimony to what is lost, displaced, or imagined anew.

The political impact of the work extended beyond the site. It became part of the wider student-led movement that successfully halted the proposed auction and deforestation of 400 acres of forest. This continuity between art and activism demonstrates what Serafini calls the “continuity between art and action.” Wait for Weight did not simply respond to the crisis; it intervened.

In the face of relentless development, the platform’s performance served as a reminder; resistance can be quiet, deliberate, and collective. Their presence at Mushroom Rock became more than a moment; it became part of a movement. By the end, what remained was not just the nest atop the rock but the shared memory of bodies moving, bending, and breaking together (see Figure 5-5a). The green netting glimmered in the dusk—not as a shroud of loss but as a sign of conscious intervention. This was art that did not shy away from the political, nor did it sacrifice poetics to protest. It insisted that both are possible—that the body can hold ritual and resistance, care and confrontation, in the same breath.

Echoing the protest slogan—“Hum jungle bachane nikle hain… Aao hamare saath chalo”—Wait for Weight stands as a living call to solidarity. Art does not only bear witness to environmental crises; it intervenes—tenderly, politically, collectively.

- Serafini, Paula. *Performance Action: The Politics of Art Activism*. Routledge, 2018.

- Davidson, Jane Chin. “Performance Art, Performativity, and Environmentalism in the Capitalocene.” *Oxford Research Encyclopedia*, 2019.

- Springett, Selina. “Art-making for Political Ecology: Practice, Poetics and Activism Through Enchantment.” *Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies*, 2021.

- Shaffer, Fern & Anderson, Othello. *Nine-Year Ritual*, 1995–2003.

- Watts, Patricia. “Performative Public Art Ecology.” *ecoartspace*, 2010s.

- Flores, Patrick D. “Difficult Comparisons: The Curatorial Desire for Southeast Asia.” 2008.

- “Chipko Movement.” Wikipedia, accessed July 2025.

- Hindustan Times. “Mourning Has Broken: View Expressions of Ecological Grief From Around the World.” 2022.

- Borasino, Teresa. “Ausangate, a Gaseous Cosmology.” *Framer Framed*, 2023.

- Khullar, Sonal. Worldly Affiliations: Artistic Practice, National Identity, and Modernism in India, 1930–1990. University of California Press, 2015.