Receiving art with vulgarity

Painting: Faun and a Girl by Max Slevogt Source: Wikicommons

If vulgarity is unrefined or coarse then why do artists bother (if at all they do) intentionally imbibing it? Antonin Artaud’s “Theatre of Cruelty,” sought the ridding of humankind’s repressed energy and rejuvenating them as its purpose. Artaud says in his seminal work The Theater and Its Double (1938), “The theatre will never find itself again except by furnishing the spectator with the truthful precipitates of dreams, in which his taste for crime, his erotic obsessions, his savagery, his chimeras, his utopian sense of life and matter, even his cannibalism, pour out on a level not counterfeit and illusory, but interior.” The inherent repressed desires of mankind are realised through vicarious thrills—be it the gladiators in Rome combating to death, or twentieth century circus where women dressed in raunchy clothes and leaned their heads inside a lion’s mouth. One may smile, make faces or puke through the performance but the eyes want more!

In 1974, Marina Abramovic, a performance artist from Serbia created a performance called Rhythm 0. During the performance Abramovic became willfully passive and stood quietly in the gallery for six hours, during which audience members were invited to use one of 72 objects placed on a table to interact with her. The objects ranged from feathers, chocolate cake, roses, to a pair of scissors, a knife, a gun, bullets and chains. Initially, the audience started with placing a rose in her hand, kissing her, and feeding her cake. It was soon followed by taking scissors off the table and cutting off all her clothes, a man trying to rape her, another loading the pistol and pointing to her head, another man cutting her close to neck and drinking her blood. She stated, “After six hours, which was like 2 in the morning, the gallerists came and announced that the performance was over. I started moving and start being myself, because until then I was there like a puppet just for them, and at that moment everybody ran away. People could not confront me as a person.” 5 To see a silently standing artist, and however anointing or disfiguring her was at the audience’s discretion alone.

- Aamir Butt, “Manto: The tormented genius” THE NATION, January 18,2016,

https://nation.com.pk/18-Jan-2016/manto-the-tormented-genius - Navarasa: The nine emotions widely accepted in Indian art aesthetics

- The research was commissioned by Encore Tickets where the team monitored heart rates and electro dermal activity of 12 audience members at a live performance. The team found that alongside individual emotional responses, the audience members’ hearts were also responding in unison, with their pulses speeding up and slowing down at the same rate.UCL,” Audience members’ hearts beat together at the theatre” (November 2017),

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/pals/news/2017/nov/audience-members-hearts-beat-together-theatre#:~:text=New%20research%20led%20by%20the,you%20know%20them%20or%20not. - Freedom Cole, “The nine affects and the Navarasa” (March 2015),

https://shrifreedom.org/ayurveda/rasa-and-bhava/ - Natalia Borecka,“The Most Terrifying Work of Art in History Reveals The True Cost of Passive Acceptance”LONE WOLF MAGAZINE, April 16,2016,

https://lonewolfmag.com/most-terrifying-work-of-art-passivity/amp/ - Apsara: Celestial Nymph

- Bhavana Akella, “Khajuraho temples defined India globally as Kamasutra land” DECCAN HERALD,September 8, 2015,

https://deccanherald.com/amp/content/499793/khajuraho-temples-defined-india-globally.html

Acknowledgements:

About the author:

Vulgarity and the “Trashy” 80s: A Case for the Double-Meaning Hindi Film Song

Sporting a shabby sherwani and a comically large moustache in Manmohan Desai’s Mard (1985), Amitabh Bachchan, the brooding “angry young man” of the 1970s and 80s, sings provocatively about a bambu (bamboo stick) erected in a tambu (tent), as he longs to be united with his bride. As the song progresses, Bachchan unambiguously assigns the phallic symbol to the bambu and performs suggestive hand gestures that often originate from between his legs. The lyrics make up for what the gestures cannot say:

Maine Jor Lagaaya,

Haath Se Bhi Dabaaya,

Par Dil Ki Miti Na Chubhan

Dulha Baahr, Dulhan Andar, Bich Mein Yeh Gore Bandar

Mera Kab Hoga Utghaatan?

(I applied force,

Pressed with my hands,

But my longing does not subside.

I am outside, my bride is inside,

And these villains stand in my way,

When will my time come?)

Hum Toh Tambu Mein Bambu is only one of many such raunchy examples that populated Hindi films of the 1980s and early 90s. Though many of them were hits at the time, over the years the double entendre songs of this period have often been met with disdain, discomfort, and even righteous rage. The 1980s in particular incite such a reaction. Ahead of the 1982 Asian Games in New Delhi, the government had temporarily relaxed import restrictions for Video Cassette Recorders (VCRs) and coloured television sets, prompting the arrival of video cassette technology to India. The following years saw the mushrooming of “video parlours” across the country, where pirated copies of films were screened at much lower costs than movie theatres. At the same time, middle-class audiences retreated to their homes that were now equipped with coloured televisions and VCR sets. Exhibitors were at a loss and the industry entered a slump, engendering the perception that the decade represents a “dark age” in Hindi cinema. This perception is closely linked to the class composition of the audiences that frequented theatres during this period, based on the assumption that the poor cinematic quality is synonymous with “poor tastes” of the working classes. The films, made on sparse budgets, were considered exploitative and tawdry in production—certainly not an aesthetic that could find an honourable place in the neat trajectory of the Indian film history canon.

The “South Indian” Influence

A prominent trend in mainstream films of this period was the collaboration with Tamil and Telugu-language filmmakers. Based on interviews conducted with Hindi filmmakers during her doctoral research, Tejaswini Ganti observes a disdainful attitude towards this “south Indian aesthetic”, which was widely considered to be louder than Hindi films. The drama was regarded as kitschy, and the songs and choreography were seen as vulgar. But scratch the surface of this supposed vulgarity, and one may appreciate that some of these “trashy” song sequences are bursting at the seams with imagery. There are lovers dancing among flowers in deserted gardens or fields, married couples engaging in pre-coital banter, and several odes to the glittery adrenaline of the disco era. The double-meaning lyrics were often a play on youthful desires, premarital sex, and the pleasures of intercourse.

Dancing in lush fields in K Raghavendra Rao’s Himmatwala (1983), Jeetendra and Sri Devi sing:

“Kaisi yeh lagan hai?

kaisi yeh agan hai?

Milke mann bhare nahi, kaisa yeh milan hai?

(what is this attachment?

what is this fire?

The heart still yearns for more, what is this union?)”

The lighthearted song (Taki O Taki) gives expression to the burgeoning romance of young lovers who no longer wish to keep their desires secret. “Aapas mein taak dhin, taak dhin ho gaya, ab kya reh gaya baaki?” says the refrain of the song, loosely translating to: “we have done the taak dhin, taak dhin together, what more is left to do?”. The term “taak dhin”, used informally to mark beats in Hindustani classical music, becomes a euphemism for the pleasures of a love consummated—what more, then, is left to legitimise this union?

Jeetendra and Sri Devi in Taki O Taki, Himmatwala (1983). GIF created through GIPHY, Video Source: YouTube

The suggestive song sequences of the period also push the envelope in a largely censorious society. Looking at Bhojpuri cinema and vulgarity in the public sphere, Akshaya Kumar posits that vulgarity is also prompted by a desire to deliberately defy repressive rules of etiquette. To an extent, the mischievous double entendre in these songs is a test to see how far an idiom can stretch. The songs are careful to only make a suggestion, and are almost never explicit. Where there are limitations to what the text can say, they find innovative ways to convey meaning. In Aayi Aayi Mein Toh Aayi from Rao’s Jaani Dost (1983), Parveen Babi bites into an apple, then dances on grassy slopes with Dharmendra. She sings about the jannats (heavens) she hides within herself, as large, inflated balls descend down the hill. The visuals can lend themselves to any number of meanings—the apple is the forbidden fruit, and the balls (seemingly an odd choice of props) could mean a rush of hormones, or a burst of fertility. The cinematic text, therefore, operates at multiple levels.

Titillation of the “Low Brow”

The 1980s and early 90s were also especially rewarding for B cinemas—small-budget films that circulate in “non-prestigious” rural markets, often including sexploitation films, adult horror, and other “low” genres. This is the time when Marathi comedy icon Dada Kondke also made his foray into Hindi films, and brought with him the risqué humour he was known for in Marathi films. The song Teri Le Loon Baanhein from Kondke’s Tere Mere Beech Mein (1984) frequently makes it to online compilations of “most perverted” Hindi songs. The meter of the song has strategic punctuations which make the lyrics more salacious than if one were to read them on paper. The song features Kondke himself, and in a particularly bawdy line he says “khol ke mujhko dede, oh khol ke mujhko dede (open it and give it to me, oh open it and give it to me)”, before the next line clarifies “khol ke mujhko dede nakli kaano ki baali”—he is only asking the woman to remove her “nakli kaano ki baali” (false earrings) so he can replace them with genuine pearl ones.

Teri Le Loon Baanhein from Tere Mere Sapne (1984)

Filmmaker and writer Paromita Vohra has spoken about the middle-class disdain towards Hindi film song sequences, with recent trends moving away from the lip sync songs. Vohra identifies the 80s as the period where song sequences became “formulaic”, prompting an effort in the subsequent decades to discard the formula and usher in a mode of realism. Kondke’s suggestive number incites discomfort because of its crude approach to sex. The lyrics are unlike the sophisticated Urdu poetry of the previous decades, and the choreography lacks grace. This form, and the generally “camp” aesthetics of the decade, add further to the contempt with which Hindi song sequences are regarded. The pelvic thrusts, over-the-top expressions and “vulgar” lyrics of these songs constitute precisely the kind of “lowbrow” body genre that is considered excessive. It is, however, notable that even women perform these “ungraceful” pelvic thrusts and are often engaging in a cheeky back-and-forth within the same double-meaning song—subversive pleasures that politically correct criticism of the “exploitation” aesthetic often overlooks. Hardly anywhere else does the Hindi film provide such a free rein of expression—let alone depict the actual act of sex on screen—than in the film song. As scholars like Ira Bhaskar have argued, the film song becomes the “language of the ineffable”.

Vulgarity and Censorship

It does not take long for the notion of vulgarity in films to enter the ambit of the censorship debate. The most common concern about these double-meaning songs and suggestive choreography, from conservatives and liberals alike, is that they will influence impressionable groups poorly. This anxiety, of course, is premised on the elite belief that the illusions of cinema will corrupt the “poor, uneducated masses”. The particular disparagement reserved for Hindi films of the 80s and early 90s, Ganti finds, stems from the dominant belief that they catered to the “front benchers”—poor, young men associated with repressed sexualities and vulgarity.

The argument against this “vulgarity”, that it corrodes Indian morality, that it is “trashy”, or that it objectifies women; the judgement is often coloured by a censorious impulse to do away with something one disagrees with. This dismissal also discards with it any potential value the form may have offered. In 1993, Subhash Ghai’s Khal Nayak ran into major controversy over the song Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai (what is behind the blouse?). The lyrics of the song combined with its visuals (of Madhuri Dixit dancing sensually in a room full of men) triggered accusations of vulgarity, objectification and titillation from different groups. But a closer analysis of the song also lends itself to a queer reading, where the song is essentially a conversation between two women.

Madhuri Dixit in Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai, Khal Nayak (1993). GIF created through GIPHY, Video Source: YouTube

The latter half of the 90s saw a concerted effort to distance from the cinema of the previous decades. The economic liberalisation of 1991, and the subsequent “Bollywoodisation” of the industry—a term proposed by Ashish Rajadhyaksha in his seminal essay (2003)—ushered in glossier family dramas that catered to diasporic markets and NRI audiences. By 1997, the first multiplex had arrived, and the following years would see a greater indulgence of the tastes of urban middle-classes who patronised these establishments. More recently, a “realistic” form, sans song and dance, is taken to be the “thinking” person’s cinema, and the gateway to establish Hindi films as a legitimate and serious form. There’s less room for the sensory pleasures of a song sequence, or catharsis through an expectation to suspend disbelief, let alone for the “vulgar” flamboyance of the 80s—a period now largely perceived as what Ganti would call the “anti-thesis of cool”.

References

- Ganti, Tejaswini. 2012. Producing Bollywood: Inside the Contemporary Hindi Film Industry. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Kumar, Akshaya. 2015. Provincialising Bollywood: Bhojpuri cinema and the Vernacularisation of North Indian media. PhD thesis. University of Glasgow.

- Dutta, Amrita. 2020. Interview with Paromita Vohra. “How song and dance made love and desire visible on screen”. The Indian Express, July 12, 2020. https://indianexpress.com/article/express-sunday-eye/how-song-and-dance-made-love-and-desire-visible-on-screen-6500784/

- Muzaffar, Maroosha. 2018. “Interview: Ira Bhaskar on Lustful Ladies in Hindi Cinema, From Mughal-e-Azam to Veere Di Wedding”. VICE, 04 June, 2018. https://www.vice.com/en_in/article/ywen4m/interview-ira-bhaskar-on-lustful-ladies-in-hindi-cinema-from-mughal-e-azam-to-veere-di-wedding

- Subba, Vidhushan. 2016. “The Bad-Shahs of Small Budget: The Small-budget Hindi Film of the B Circuit.” BioScope 7(2) 215-223. DOI: 10.1177/0974927616668009

Header Image Caption: Sri Devi in Nainon Mein Sapna, Himmatwala (1983). Image screenshotted from YouTube

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- Suhasini Krishnan is a student of Film Studies at Ambedkar University, Delhi. Her interests lie in popular Hindi cinema, the unique idiom of song sequences, and ‘Bollywood’ stardom as a phenomenon. She has worked as a journalist since 2016, and her writing has featured in The Quint, Homegrown, Times Internet, and Critical Collective.

The Phantom of Vulgarity around the Voluptuous Body

A complete break from defying conventional understanding of body and gender appears to be nearly unachievable. Often efforts to do so succumb to the brackets of dominant definitions, albeit unintentionally. In the context of Indian art history, the term fat is remotely invoked. The wave of presumption to measure the moral quotient in accordance with the “voluptuous” body was ushered in with the onset of the British Empire[i]. However, it is beyond the scope of this text to historically contextualise and trace the visual representation of the fat body of women across the genres in India. The ensuing discussion is an attempt to underscore the exhilarated interest of the art practitioners of the late nineteenth–twentieth century, especially in popular culture, to perpetuate the representation of the uncontained body as a site of mockery that further cemented fat-phobia, clinically termed as lipophobia.

A lost opportunity was the 2018 horror-comedy movie Stree. The movie received critical appreciation for its ironical undertones as it showcased men experiencing everyday challenges that are otherwise faced by women. Paranoia to take a late-night stroll, the need to follow appropriate dress code to avoid the male gaze, and the fear of being labelled a social pariah if the partner was chosen by the person and not parents are a few of the anxieties women are made to experience in the patriarchal societal structure. Within the satirical framework, the men of the region Chanderi are forced to step into women’s shoes as an act to ward off the invisible yet possible threats of the looming danger from the spirit Stree. Against the contingent of men, the movie about the subversion of the patriarchal discourse on women and social decorum has three women who make their presence on the screen, besides Stree (the apparition): Stree—led by Flora Saini; the lead protagonist—Shraddha Kapoor who is a protector-cum-witch; the one-time performer—Nora Fatehi; and the sex worker—Atmaja Pandey, who appears twice.

The movie, which wants to extend the feminist point of view, falters by representing its female characters through stereotypical bodily conventions. Instead of disturbing the social construct, the movie perpetuates the parallel between the body of the woman and her character. The discerning eye cannot ignore the synonymy of wasp waist with the sensuous charm and polite speech of Kapoor, and the fat body of Pandey with raw expressions and crass language. Even though the movie nudges its male characters to draw a new line of thought on feminism, it confines the female characters to a stereotypical formula. The non-adherence to bodily standards of a decent society, the fat body attracts the stare from the viewers of the comfort zone.

The movie, in an effort, to make the men get a taste of their own medicine remains woefully short to provoke us to see the world under a new lens stripped of bodily conventions. The consumerist popular culture opens an opportunity to navigate the contradictory approaches to derivative prejudices. Rather than having monolithic views feeding into confirmation bias, the multiple perspectives invigorate critical discussion. Under the satirical tones, the oblique treatment of the excess flesh creates a lacuna to be filled by another celluloid, free of the burden to make representation palatable to the larger audience.

Before Raja Ravi Varma’s representation of female divinities on oleographs, the goddesses as a manifestation of purity were sacred enough to be guarded against the public eye. Soon the mass production of the lithographs and oleographs in the nineteenth century heralded the way for mass art production, loosely termed calendar art. It promoted a standardised representation of woman-the semi-clad curvaceous body holding an odd posture.

Image Credits: Stolen Interview, Raja Ravi Varma, Courtesy: Creative Commons

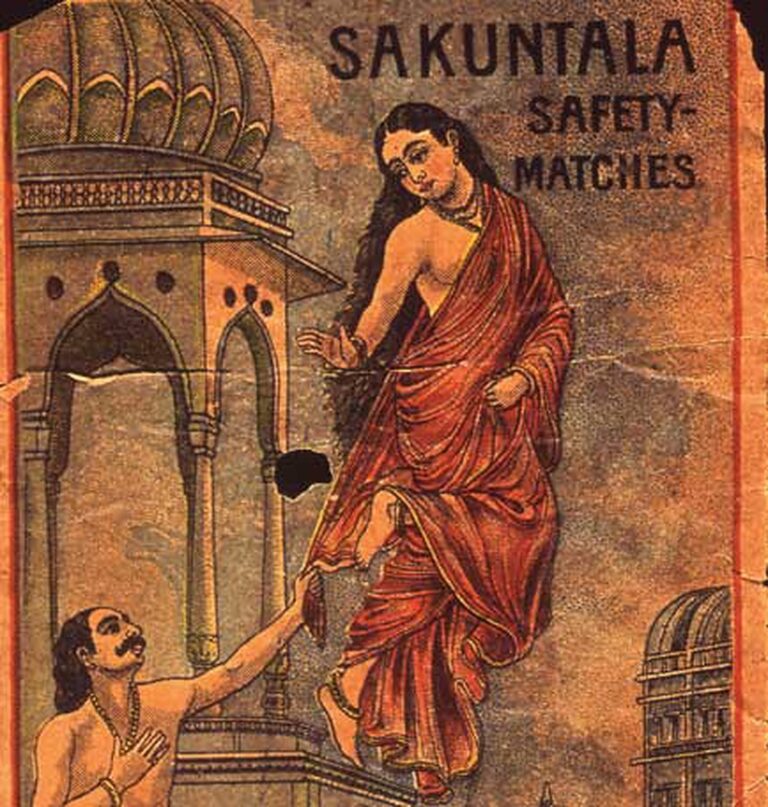

As the goddess was moved from within the walls of sanctity into the public sphere or bazaar, it turned into a profane woman and no longer a subject worthy of emulation. Exemplifying the same is the visual representation of Sakuntala and Dushyanta on a matchbox.

The Calcutta-based Parimal Ray collects an array of the paraphernalia of the bygone era’s popular visual arts—available at fairs, junkyards, and streets. In one of his collections, a matchbox carries the image of Shakuntala in a red-saree and the gesture of her hand pointed towards Dushyanta suggests refusal. If the traces of Varma’s stylistic approach to the visuals are not hard to ignore, it reinforces the “Swadeshi” flavour. Kajri Jain in her book Gods in the Bazaar explains the major critiques of the calendar art that has stemmed from the lithograph industry: “On aesthetic grounds, [this genre of printed image] has been condemned its derivativeness, repetition, vulgar sentimentality, garishness, and crass simplicity of appeal…” Conforming to the zeitgeist of the times, the image of Shakuntala, made popular by the lithographic prints, borders on the norms of domesticated modesty and unabashed display of desires.

Image credit: Sakuntala, Matchbox Label, Early 20th Century, Courtesy: Parimal Ray, From the archive of CSSSC

The disjunction between the art period based on the temporal axis of tradition and modernity; access to the high or low art set the ground of aesthetic tastes: refined and vulgar.

The Kalighat paintings of the same time turned women into a spectacle for the commoners. The rose in the miniature art of medieval India served the purpose of both euphemism for and symbolism of representing the emotive sexual desires. Years later, the red flower in the hands of the so-called crass women in Kalighat paintings was reduced to a degenerative symbol of sexual advances: the domestically tamed flower is not to be turned into an immoral subject of public viewing[ii]. When the private acts of ease, leisure, and refinement are transmuted into the domain of public, it falls from the state of grace to debasement. Here, the metaleptic rose once again confirms the inherited frames of looking and perceiving the hackneyed representations of the epithet vulgar.

Image credits: Maid Bringing a Hookah to a Lady, Courtesy: Creative Commons

The critical discussion around fat female bodies as morally insufficient has remotely gained momentum in the western discourse of visual arts. It is predominantly an area of research interest for disciplines including media, cultural, and sociology[iii]. Despite academic scholarship, across the disciplines, on the body, especially in India, intellectual curiosity could not detach an array of adjectives from the body. More often than not, dissuaded as an object of ridicule, the dominant cultural discourse constructs a spectacle on the body that could not fit within the parenthetical appropriate measurements. To liberate the voluptuous body from the phantoms of the vulgarity, its visual representation devoid of clichés on the popular platforms is the first step forward towards a positive viewpoint. It is easier said than done. The necessity to reconfigure female fat bodies opens critical dialogue on the social construction of parallels between crassness and the uncontainable body.

It could be argued that visuals do not predominantly account for the fear of fat, the visceral responses to the desirability of wasp waist, which are embedded in the long social and medical history. Furthermore, the visuals are even dubbed as apolitical having little significance on the minds of the audience. Having said that, it cannot be denied that weaving in and out of the reversal chronology[iv] is the notion that the popular culture with these obsolete portrayals triggers an implicit bias. The importance attached to ‘what is framed’ and ‘why it is framed’ prompts to scrutinise the internalised behaviour of the immediate consumer of the popular culture—the audience. The regular engagement with the floating abundance of the visuals set the yardstick to measure the standards of body shapes and asinine behaviour. Subsequently, for the interpellated subject, the task to undo the epistemic structures is complicated when the surge of the visuals acts as a reification of truth in mainstream narratives. Hard to be removed from the site of public spectacle, the representation of the body is not exclusive to personal and political framework of assessment.

[i] Nead, Lynda. Myths of Sexuality: Representations of Women in Victorian Britain. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1988.

[ii] Archer, Mildred. Indian Popular Painting In The India Office Library (London), New Delhi: UBS Officer. 1977.

[iii] Snider, Stefanie, “Fatness and Visual Culture: A Brief Look at Some Contemporary Projects.”, Fat Studies 1, no. 1, (2012): 13-31.

[iv] Nietzsche, Friedrich, Werke, Translated by Schlechta. München : C. Hanser Verl., 1966.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dilpreet Bhullar is a writer-researcher based in New Delhi, India. She has an MPhil from the University of Delhi in Comparative Literature. She is co-editor of the books Third Eye: Photography and Ways of Seeing and Voices and Images. Her essays on visual sociology, identity politics and refugee studies have been published in books, journals and magazines including Designing (Post) Colonial Knowledge: Imagining South Asia (Routledge), The Third Text (Routledge), South Asian Popular Culture (Routledge), Indian Journal of Human Development (Sage Publications), Himal Southasian, and the digital archive www.criticalcollective.in, to name a few. She is associate editor of the theme-based journal on visual arts, published by India Habitat Centre, and feature writer at

STIRworld.com

Drunkenness: A saga of derision and disgrace

Satyasoma: Pour this Goddess Liquor into a cup and off come the lovely dress and ornaments; reconciled are the quarreling lovers; made bold, the young; and full of life, the flirtations of love!

– Excerpt from Michael Lockwood and A. Vishnu Bhat,”Metatheatre and Sanskrit Drama”

#LiquorShops Meme Source: Twitter

Comedy is evoked by scenarios of surprise, exaggeration, disproportion, shared awkward experiences, surrealism, irony, mockery, pun, or defiance. Henri Bergson says that a spectator would find contrived and mechanical movements comical. This is because they find it silly or absurd; essentially something which is considered abnormal in a society induces humour. Arthur Koestler says as humanity evolved, aggression was replaced with comedy. A comic situation arises only when the spectators don’t empathise, rather distance themselves from the characters. Comedy is also distinguished as high and low. It was commonly misconstrued that high comedy, which is witty and critical of life, is reserved for the educated. While low humour which entails bawdiness, silly visuals, drunkenness and physical humour, can be enjoyed by anyone.

Farce, a low form of humour is purely meant to induce laughter. The plot is set in an improbable situation, sometimes even incomprehensible. It is replete with absurd miscommunications and mistaken identities. The characters are stereotypical, often ignorant and belonging to lower social class[i]. Under these circumstances, a person under the influence of alcohol becomes an easy target for a protagonist.

A religious tradition which entails the practice of regular intoxication could have been an easy choice for a farce in the seventh century. Mattavilaasa Prahasana(m)/ A Farce of the Drunken Sport is a one act farcical play set in Kanchipuram. The playwright is the Pallava ruler Mahendra Varman whose epithet was Viciracittan, the man with the prowess of thinking unique. For an emperor who reveled under the idea of “thinking outside the box”, he penned two farces i.e. Mattavilasa Prahasana and Bhagavadajjuka[ii] which highly satirizes today’s heterodox traditions of South India. In Sanskrit theatre tradition, Prahasana—a farce, enlists a few characteristics—it is a one act play with predominance of low comedy. The object of laughter is improper conduct by ascetics, courtesans, rogues, etc. Unlike Hellenistic theatres, a farce in Sanskrit theatre incorporates elements of irony, satire, and mockery. It is essentially a lower form of comedy as it involves improper conduct—drunkenness in the case of Mattavilaasa Prahasana. These farcical plays could be marked as an innovation in Sanskrit theatre tradition, as there are no other renderings of farce available to the larger demographic. Satire usually comments on the hypocrisies in society or traditions. Hence, it can be assumed that the mentioned religious practices were prevalent during Mahendra Varman’s time[iii]. Mattavilaasa Prahasana gives a distorted idea of the religious tensions during the seventh century in Kanchipuram. This play, while bringing out the religious laxity and bigotry, there is an underlying tone of praise for Kanchipuram under the rule of the illustrious Pallava Empire.

The play’s characters follow three different traditions that are satirised i.e. Kapalika[iv], Buddhist, and Pasupata[v] tradition. In passing, the Jain tradition is also included. The protagonist of the play Satyasoma, follower of the Kapalika tradition, along with his wench[vi] Devasoma, enter the city of Kanchipuram visibly drunk. The beautiful city is in celebration as the two of them enter another tavern to drink more. They praise the tavern which is complete with drunken revelry, a paradise for the Kapalika. While collecting alms, the duo realise that their Kapala, the skull bowl is missing and nowhere to be found. Satyasoma concludes that it must have been either stolen by a Buddhist monk or a dog, as the bowl contained roasted meat. At this inopportune time, a degenerate Buddhist monk Nagasena, contemplating indulgence in intoxication or ritual intercourse, enters the scene and is accused of theft. After a few scathing remarks are exchanged, a drunken brawl ensues until Bhabrukalpa, a practitioner of Pasupata tradition tries to resolve the matter. Bhabrukalpa, also a degenerate, only wants to add fuel to the fire as Devasoma left him to be with Satyasoma. Bhabrukalpa praises the righteousness of the judiciary system under the rule of King Mahendra Varman. Just then a madman enters the scene carrying the skull bowl. After Satyasoma receives his bowl, he thanks Nagasena and Bhabrukalpa with respect and departs. While this play epitomises the Pallava reign, it outwardly berates religious practices, especially Buddhism.

Kutiyattam presentation of Mattavilaasa Prahasana(m) Courtesy Kalamandalam Sangeet Chakyar & K.K. Gopalakrishnan

Jessica Milner Davis comments “The comic spirit of farce delights in taboo-violation, but avoids implied moral comment or social criticism and prefers to debar empathy for its victims. This combination is vital for farce to succeed.” Under her categorisation, it is likely that Mattavilaasa Prahasana falls under Equilibrium or Quarrel farce where two opposing parties quarrel without resolution, restoring the same balance. While Satyasoma’s drunkenness is the crux on which the plot rests, the Buddhist traditions and philosophies are satirised and ridiculed. This could have been a significant taboo in the seventh century Kanchipuram. The playwright being a supporter of Saiva revival has brought out his thoughts about heterodox traditions through this text. The Buddhist complains about his traditions and wonders why Buddha has not included alcohol and ritual intercourse while allowing every other comfort. On the other hand the Kapalika not once dislikes his tradition, and he ruthlessly comments on Buddhist and Jain traditions. Satyasoma also compares a Buddhist monk to a dog trying to steal his skull bowl because of the roasted meat. In the end, it is a dog which runs away with his skull bowl. There is also a statement where the Kapalika says Buddhist tenets are stolen from Mahabharata and Vedanta. Usually the play is seen as a taint to the Kapalika tradition, it is more likely to be so on the Buddhist tradition which was on a slow decline. Nagasena only comments on Satyasoma’s regular drunken antics and tries to stay away but in vain. Satyasoma’s character is represented as a shallow drunk who slurs and loses his motor skills but the Kapalika tradition is upheld which is clear in the benedictory verses (Naandi Sloka). Throughout the play, Satyasoma’s drunken horseplay is used not just as a source of comedy but an easy reason to cast aspersions.

This play, when represented in Kutiyattam has a completely different connotation. Lord Shiva’s dance to appease the angry Goddess Bhadrakali is equated to Mattavilaasa Thirunrittam, the intoxicated dance. Even though there is a divine association to the protagonist, he still provides comic relief as a drunken man by exiting the stage looking for alcohol, leaving the audience light hearted.

Barney Gumble, The Simpsons Character

Created by: Jay Kogen & Wallace Wolodarsky

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Infusion of satire in a drunkard’s words has been a tool to question the society and its norms. Examples of this can be found across different theatre traditions, television series, and cinemas. Apart from Mattavilaasa Prahasana, drunken characters making a fool of them and taunting others are included in Nagananda, written by Emperor Harsha of the Vardhana Empire. In Twelfth Night, Sir Toby Belch mouths witty comments including his blatant disregard for drunkards even as he is one himself. Moliere uses drunkenness as a veil in a marital relationship. In Anton Chekov’s Drunk, drunkenness has been used as a means to reveal darkest personal secrets and in turn the societal perception of wealth. Barney Gumble from the animated television show Simpsons is always seen at Moe’s Tavern burping loudly, while the narrative also shows his life overturned by alcohol time and again; Tyrion Lannister from Game of Thrones whose sharp remarks on society are a few examples of the drunken double-edged jokes. Drunkenness has always been a source for easy physical humour where the character gets away with any comment they make under the garb of intoxication. While the character embraces low comedy, the resultant effect is satire or black comedy. To sum up, as Satyasoma befittingly says, the goddess liquor removes the embellishments and only reveals the truth, however loving, remorseful, or sardonic.

References

- Tolman, Albert H. “Shakespeare Studies: Part IV. Drunkenness in Shakespeare.” Modern Language Notes 34, no. 2 (1919).

- Donato Totaro, “Two Minds on Comedy: Arthur Koestler vs. Henri Bergson”. Volume 16, Issue 11-12 / December 2012 {https://offscreen.com/view/koestler_vs_bergson}

- Farrell, Joseph. “Fo and Feydeau: Is Farce a Laughing Matter?” Italica 72, no. 3 (1995). www.jstor.org/stable/479721.

- Gopalakrishnan K.K., Mattavilaasa Prahasana in Kudiyattam.

- Jessica Milner Davis, “From the Romance Lands: Farce as Life-Blood of the Theatre” At Whom Are We Laughing?: Humor in Romance Language Literatures, 2013 {https://www.cambridgescholars.com/download/sample/57921}

- Lloyd Murle Mordy Jr., 1965. Farcical elements in selected comedies of Moliere. {https://core.ac.uk/reader/33368734}

- Michael Lockwood and Vishnu Bhatt A., 2005. Metatheatre and Sanskrit Drama, Second Revised and Enlarged Edition. Tambaram Research Associates.

- Translated by Palmer Boyd, 1999. Nagananda – Harsha. In Paranthesis Publication, Sanskrit Drama Series. {http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/nagananda_boyd.pdf}

- Raghavan, V. “Sanskrit Drama: Theory and Performance.” Comparative Drama 1, no. 1 (1967). www.jstor.org/stable/41152424

- Edited and Translated by Unni N.P., 1974. Mattavilaasa Prahasana of Mahendravikramavarman. College Book House.

[i] The Three Stooges is a classic example for farce. There is no underlying plot, the characters are from a lower social class and there is a high usage of slapstick comedy and horseplay.

[ii] There has been an ongoing debate about the authorship of Bhagavadajjuka. This essay takes Michael Lockwood and A. Vishnu Bhat’s assertion of the playwright

[iii] Xuen Xang’s travelogue mentions the large number of Buddhist monasteries in Kanchipuram during the same time period

[iv] Kapalika tradition is a form of non puranic Shaivism. Traditionally they carry an empty skull bowl (Kapala) for alms. One of their rituals entailed alcohol consumption.

[v] Pasupata tradition is one of the oldest Saiva devotional and ascetic movement

[vi] N. P. Unni’s translation of Mattavilaasa Prahasana uses the term wench for Devasoma. She is probably called so as she changes her allegiance from Pasupata to Kapalika tradition along with changing her partner.

Header Image credit: Cover page of Mattavilaasa Prahasana by Dr. N. P. Unni, Nag Publishers Courtesy: K. K. Gopalakrishnan

About The Author

Kuzhali Jaganathan is an arts manager and a dance practitioner. She takes immense interest in studying cultural practices, and it’s reflection, and implications in arts and literature. Apart from being an MBA, she has completed courses on Buddhism and Tantric Practices. She aspires to be an academician.

Virile Desires? Scenes of ‘unnatural’ sex in Rajasthani paintings

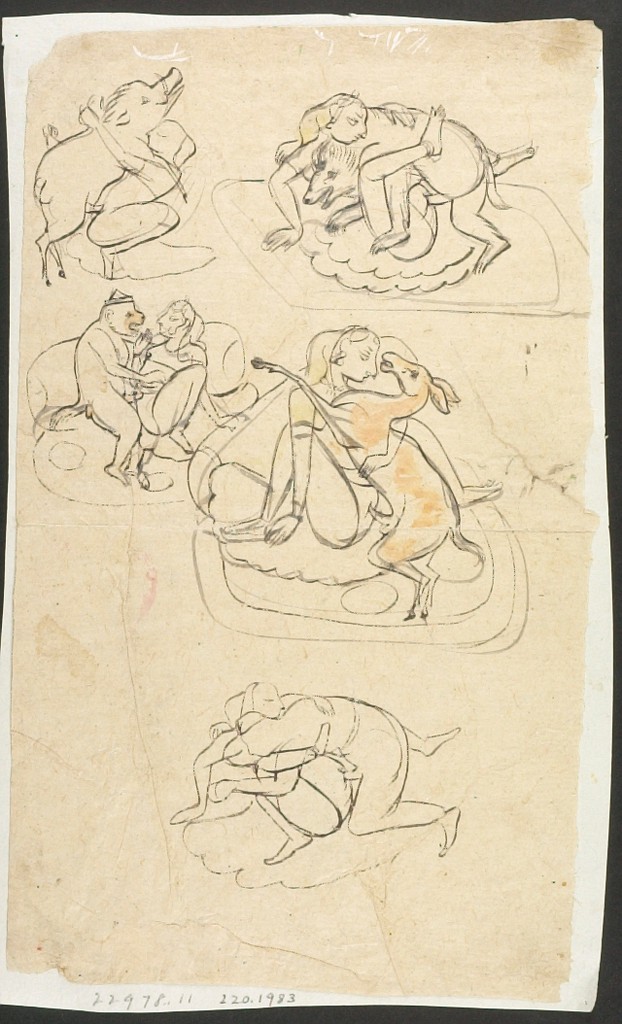

The above image (Fig.1) seems to be a preparatory or practice drawing/sketch in which women are depicted sprawling their legs for a wild boar, monkey, black-buck, and a man for copulation. From erotic scenes adorning temple walls to “ass-cursed” stones (gadhegal) depicting a woman being penetrated by a donkey and beyond[ii], the expansive range of artworks depicting sexual activities give a glimpse into South Asia’s complex past, which has much to offer when we think of sex and sexuality. Likewise, Fig.1 makes us wonder: why was it created? Who was the spectator? In an attempt to understand these “unnatural” scenes, this essay offers a preliminary inquiry of this complex subject which remains understudied.[iii] The examples used here belong to the region of Kota and a brief overview of its artistic traditions and histories shall help us to understand the context of their production.

Fig.1: Erotic Vignettes of Intercourse of Women with Animals and a Man, circa 19th century, Kota, Rajasthan, India. Collection: Harvard Art Museums. Link: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/217581?position=3

Enveloped now within the state of Rajasthan in northern India, Kota, in 1631 CE was an independent princely state established by Rao Madho Singh (r. 1631-48).[iv] Painting as an activity at Kota arguably began as early as the 1650s. By the 18th century, Kota was one of the major centers of court paintings with accomplished artists executing a variety of subjects – sensitively rendered flora and fauna (most notably elephants), ecstatic hunt scenes and a wide range of surviving preparatory/practice drawings, all of it giving a glimpse into the artists’ psyche and lives.[v] Erotic scenes were a conventional theme among court painters. Kota painters never failed to convey the passion through their “undulating line[s]” as seen in Fig.2.[vi]

Fig.2: An amorous couple and two women, 19th century, Kota, Rajasthan, India. Collection: Harvard Art Museums.

Link:https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/217615?position=41

Fig.3: The great orgy of Maharao Shatru Sal II, mid-19th century, Kota, Rajasthan, India. Collection: Harvard Art Museums. Link: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/310594?position=0

A better picture is available on Flickr: https://www.flickr.com/photos/heleenmeijer/41975279091/

Almost an expansion of Fig.1, the above scene is set against a dark dramatic gloomy sky with curling clouds, crowded with figures. Through the lush green mountain and the marbled palace-like structure, the painter distinctly splits the scene into two. Only a close inspection of the painting unravels this ‘potpourri’ – the upper part depicts a variety of animals and birds in copulation; parakeets, ducks, goats, tigers, wild buffaloes, camels, bull-cow, deer, sloth bears, dogs, horses, wild boars, nilgais, and even elephants. Slowly as our eyes move down, few male-animals and men are seen copulating with women in a variety of positions and “oblong pillows and small cups strategically placed to collect body fluids are scattered all over the lower half of the painting”[vii]. While some women seem to ‘worship’ the enormous penises of three bearded figures who could probably be ash-smeared saints, one in the lower right even performs fellatio on him.[viii] Amidst all this, on the lower right, a woman is giving birth to a child. So what do we make of all this?

I suggest, looking beyond this painting may guide us further. Broadly, in many Hindu traditions, kama (desire or sexual love) is one of the four important aspects of life[ix], and especially for kings, kama was their rajadharma (king’s obligation).[x] Among the texts on “eroticism”, Kamasutra (in Sanskrit; arguably circa 3rd century CE[xi]) of Vatsyayana is perhaps the best-known and may give us some clues regarding this scene.[xii] The classification of “hero” (nayaka) and “heroine” (nayika) in Kamasutra, encompasses a chapter on sexual typology divides men into hares, bulls and horses and women into deer, mares and she-elephants.[xiii] Bulls and horses are signifiers of virility and power. If read carefully along with the text, some sexual positions reveal similarities with the painting. For e.g. “a ‘doe’ positions herself in such a way as to stretch herself open inside”.[xiv] And “…When both thighs of the woman are raised, it is called the ‘curve’. When the man holds her legs up, it is the ‘yawn’…”[xv] (see Fig. 3.1, with numbers marked). This is not to suggest that Kamasutra is the direct source of this painting, but we should not be surprised to find the painting’s roots in this as many Hindu/Rajput rulers “reached back” to these texts (other examples include Rasikapriya, Gita Govinda, Ramayana among others) and were “deeply inflected” by early South Asian aesthetic and visual traditions, as Molly Emma Aitken discusses.[xvi]

Fig.3.1: Detail from Fig.3.

Before we conclude, let us return to the painting. The scene almost camouflages an important figure on the left just above the blue figure. He is none other than the then ruler Maharao Shatru Sal II of Kota (r. 1866-89), who appears to be the most virile and powerful man among all in the scene (Fig.3.2). Another similar partly damaged scene depicts Shatru Sal II’s father Ram Singh (Fig.4).

Fig.3.2: Detail from Fig.3

Fig.4: A Royal Figure and Several Courtesans Engaged in Amorous Activities, circa 1840 CE, Kota, Rajasthan, India. Collection: Harvard Art Museums.

Link: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/art/217612

This not only confirms his prime position as an “ideal lover”, pleasing five women at the same time (something which no other figure is doing in this scene) but also his courtly masculinity and supremacy. Paintings were a powerful mode to convey such messages. In her seminal essay, Kavita Singh has argued how a Mughal painting of Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’ (r. 1719-48) might have served as a visual device to flaunt his lost virility after his “motor reflexes deteriorated at an early age, affecting his control over his lower body.”[xvii] Similarly, from circa 1877 CE, Maharao Shatru Sal II fell “quite ill and never really recovered”.[xviii] Could this be his way of expressing his sexual power? Besides, the continuity of the composition from father to son emphasizes their clan’s virility and legitimacy. Another comparison of the lowest part of the scene with an 18th century “gang-rape” scene from Mewar complicates this further.[xix] Molly Emma Aitken has published the below image (Fig.6) and a similar later version from Jodhpur. While examination of the entire scene (Fig.6) is beyond the scope of this essay, I agree with her interpretation, and offer a few thoughts – scenes depicting an “orgy” usually occur in an intimate setting of a palace or a terrace with a well-arranged bed/chamber including accoutrements to ignite passion and/or inclusion of signs of love like a pair of birds. With a rather dull background, this scene depicts a woman with legs sprawled while some men can barely wait for their turn; a figure in the lower right appears to be manscaping or performing circumcision or chopping off his own penis (perhaps a pun?) while others are violently fighting for their turn – this hints at the complexity which, I argue, goes beyond the conventional erotic or sexual scenes.

Fig.5: Detail from Fig.3

Fig.6: An Indian painting, circa 1740 CE, Mewar, Rajasthan, India. Source: https://www.uppsalaauktion.se/auktioner/?auction_name=20161206&catalog_nr=345

The practice of citing, quoting or copying of figure(s) and reusing compositions was common among artists, and following the explanation of Molly Emma Aitken , many of these compositions “were intended to create new meanings from their curious combinations….composite pages and marginal figures tended to invite the spectator to search for relationships among them and to create stories to justify their combination.”[xx] While it is possible that this quotation of “gang-rape” into this “orgy” was unintended or “lost in translation”, but “at the same time it seems likely that unintended connections were also a welcome part of the game of paratactic pictures”.[xxi] Does the inclusion of “gang-rape” hint on the horror of sexual acts?[xxii]

While the scene remains a mystery, any definitive answers at this point may result in a murky understanding of the layered world of South Asian painting. Instead, we would do well with meditating over why must we look at these?

Examining these “erotic fantasies” unravels the complexity of desires, especially in a pre-modern era. Not only these reveal how desires were understood in the courtly circles, it also gives a glimpse of how the artists envisioned it. I argue, here, the visual becomes a device to highlight masculinity and virility – one wonders if there is an exact textual source which is waiting to be discovered to further understand these complex paintings.[xxiii]

Acknowledgements:

This essay is an excerpt from my on-going research on sex and sexuality in pre-modern South Asian art. I am grateful to the Write|Art|Connect team for giving me this opportunity to pen down this essay and the editors for their feedback. I am indebted to Kavita Singh, Niharika Dinkar, David Gordon White, David Smith, Pronoy Chakraborty, Adira Thekkuveettil, Deepthi Murali and Aishani Gupta for their guidance. My selection and participation in the Likho Citizen Journalism Workshop (2018) aided me to look at gender more carefully – in particular, the guidance of Sonal Giani & Koninika Roy was helpful. Many conversations with Ruth Vanita have moulded my understanding of gender and sexuality in South Asia. This paper also owes much to the encouragement and feedback of Padma Shri Dr. Prakash Kothari (sexologist).

[i] This paper deals only with the scenes of ‘bestiality’ and ‘gang-rape’ in early modern South Asian painting. I have borrowed the term ‘unnatural’ from the modern legal lexicon of India. Trigger warning: Sexually explicit images.

[ii] For a general reading, see Dr. Alka Pande and Lance Dane, Indian Erotica (New Delhi: Roli Books, 2001). Also see Devangana Desai, Erotic Sculpture of India: A Socio-Cultural Study, 2nd ed. (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1985). On gadhegal, see K.F.Dalal, S. Kale and R. Poojari, 2015. Four Gadhegals Discovered in District Raigad, Maharashtra. Ancient Asia, 6, p.Art. 1. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/aa.12320. See Dr. Prakash Kothari, Erotica: The Art of Loving (Mumbai: VRP Publishers, 2010). An intriguing parallel of ‘unnatural’ sex scenes can also be found in Japanese Shunga. See Timothy Clark et al., eds., Shunga – Sex and Pleasure in Japanese Art (Leiden: Hotei Publishing, 2013).

[iii] It is also important to note that my examination is based only on the available photographs of the paintings from web sources.

[iv] Rao Madho Singh was one of the two sons of Rao Ratan Singh of Bundi. The rulers were from the Hada clan of Rajputs and bore the titles of Rao or Maharao.

[v] For a book-length study, see Stuart Cary Welch, ed., Gods, Kings, and Tigers:The Art of Kotah (Munich: Prestel, 1997). Also see the extensive scholarship of Joachim Bautze, Woodman Taylor and Milo Cleveland Beach.

[vi] Ibid., 20. Also see Natalia Di Pietrantonio, “Pornography and Indian Miniature Painting: The Case of Avadh, India,” Porn Studies 7, no. 1 (January 2, 2020): 36–60, https://doi.org/10.1080/23268743.2018.1532808.

[vii] Sunitha Das has examined this painting in a blog-article. She notes that the painting gestures towards Tantrism. My preliminary investigation has not yet given me any direct signs of Tantric rituals, but it is difficult to comment further before examining the in-person with clarity. However, David Gordon White has suggested to me that this scene has nothing to do with Tantra (email conversation, March 16, 2020).

See: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/tour/women-in-south-asian-art/slide/10299

[viii] Again, there is no certainty about this and figures painted in light-blue may not necessarily be Shaivites but as they are also holding rudraksha mala which is especially seen among Shaivite figures, there is a possibility.

[ix] The other three being Dharma, Artha and Moksha. This varies in different sectarian traditions. See Catherine Benton, God of Desire – Tales of Kāmadeva in Sanskrit Story Literature (New York: State University of New York Press, 2006). A

[x] See Kavita Singh, ‘The Congress of Kings:Notes on a Painting of Muhammad Shah’. In Molly Aitken (ed.) A Magic World: New Visions of Indian Painting (In Tribute to Coomaraswamy) (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2016). Also see Anna Jackson and Amin Jaffer, eds., Maharaja: The Splendour of India’s Royal Courts, V&A Publishing (London, 2009).

[xi] Dr. Prakash Kothari’s research dates the text to circa 351-375 CE.

[xii] While the term erotic or eroticism does not encompass the larger understanding of what these texts convey, it gives a basic understanding. Other notable texts include Rati Rahasya of Pandit Kokkaka, Ananga Ranga of Kalyanmalla. It is interesting to note that among all these, at least Kamasutra does not look at sex between human and animals in a positive light. An important read from a gender perspective, see Shalini Shah, Love, Eroticisim and Female Sexuality in Classical Sanskrit Literature: Seventh-Thirteenth Centuries (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers, 2009).

[xiii] See Daud Ali, Courtly Culture and Political Life in Early Medieval India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 216; Vātsyāyana, Wendy Doniger, and Sudhir Kakar, Kamasutra (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 28-29. This is also repeated in Ananga Ranga.

[xiv] Doniger and Kakar, Kamasutra., 51.

[xv] Ibid., 54.

[xvi] See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D8fw_NmkSZc&t=776s

[xvii] See Kavita Singh, ‘The Congress of Kings:Notes on a Painting of Muhammad Shah’. In Molly Aitken (ed.) A Magic World: New Visions of Indian Painting (In Tribute to Coomaraswamy) (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2016).

[xviii] Welch, Gods, Kings, and Tigers: The Art of Kotah., 56.

[xix] This and another version of a similar scene has been published in Molly Emma Aitken, The Intelligence of Tradition in Rajput Court Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), 96. While she uses the two images to talk about how compositions are copied, her identification of both the scenes call it a “gang-rape scene”. Parallel scenes can be found in Japanese erotica (Shunga). See Kazutaka Higuchi and Alfred Haft. “No Laughing Matter: A Ghastly “Shunga” Illustration by Utagawa Toyokuni.” Japan Review, no. 26 (2013): 239-55. Accessed July 3, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/41959826.

[xx] Molly Emma Aitken, “Parataxis and the Practice of Reuse, from Mughal Margins to Mīr Kalān Khān.” Archives of Asian Art 59, no. 1 (2009), 96.

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Ibid., 99. Discussing a painting depicting intoxicated mystics and assorted subjects, she writes, “Tradition makes the divisions and their operations implicit. The viewer may be invited to wring from this spread of disparate scenes a meditation on intoxication: the intoxication of the lovers in the upper left, of the elephants in mast (intoxication) at the top, of the mystics on drugs, and of the victor in the hunt or in battle with his enemy.”

[xxiii] To add David Smith’s interesting take on this painting, “There can surely be no doubt that the painting was intended to have an aphrodisiac effect on its royal owner, to spur him on. The painting is certainly a representation of the universality of sexual love, where even asceticism denotes sexual power in a universe that is overwhelmingly sexual.” See David Smith, “Visual Representations of Aphrodisiacs in India from the 20th to the 10th Century CE,” in A World of Nourishment – Reflections on Food in Indian Culture, ed. Cinzia Pieruccini and Paolo M. Rossi (Milano: Ledizioni – LEDIpublishing, 2016).

About The Author

Based in Ahmedabad, Vinit Vyas works on early modern visual and material culture of South Asia, particularly court and devotional painting traditions. He graduated in Art History from the Dept. of Art History & Aesthetics, Faculty of Fine Arts, MSU Baroda in 2018. With an interdisciplinary approach, he also delves into religious studies, gender, sex and sexuality, languages, and text-image relationships. From 2015-2018, Vinit worked as a summer research intern at the Mehrangarh Fort Museum, Jodhpur, and has served as a visiting and guest faculty teaching South Asian art history at the National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad. He authored an introductory essay for the 2018 exhibition Luminously between Eternities and his other writings have appeared on The Heritage Lab, Sahagamana, and Virasat-E-Hind Foundation. Strengthening his research interests on Asian erotica, sexuality, and western Indian painting traditions, Vyas is co-authoring a catalogue on Rajasthani paintings and has also contributed a chapter in a forthcoming edited volume on the princely states of Gujarat.

The power and promise of the flip-word “vulgar”

The word “vulgar” evokes disapproval that may border on disgust; and it commonly runs top-down from the perspective of a beholder of self-proclaimed “finer” sensibility, casting judgment on objects and acts deemed “lowly”, “common” or “abject”. Since the advent of “classicism”, post-Enlightenment, which the Merriam-Webster defines as “adherence to traditional standards (as of simplicity, restraint, and proportion) that are universally and enduringly valid”, this perspective gains a renewed-validity and results in the imposition of a variety of corrective-measures. Measures, which aim to temper, reign-in and literalize the fluidity of lived traditions by adhering them to the “correctness” of an original text to reinstate past-glory; thereby driving the divide between the “classical” and the “common” even deeper, where the commoner is not only to be kept at an arm’s length but even held suspect and therefore to be controlled as his untamed and vulgar proclivities may well pose a threat to the project of (re)instating glory.

The use of the word “vulgar” along with its corollaries such as obscene, cheap, low-life, crude, tasteless, crass, indecent, indelicate, excessive, shameless, obnoxious, uncouth, etc. is not only subjective but also relative. It operates, rather effectively, as a gesture of distancing between the “refined” and the “crude” and conventionally remains the prerogative of the former. But what is of note here is that it may mean or imply quite differently from the perspectives of the “that which distances” and the “distanced”. As much as it tells us something about the identity of the object for which it is adjectively employed, it also gives us a glimpse into the mindset of the user. Through the prism of the word, both parties, the user and the receiver, become momentarily privy to attributes of the other; though, historically, only one perspective has been permitted and privileged, that of the caster of the word, the sophisticate. The word then comes to resemble a coin with equally valid flip-sides, except that in this case, the currency of the two sides might be unequal and they in turn may each foster a different set of corollaries.

Historically, the haves, the sophisticates, or the classicists have invented systems and created constructs that serve to continually undermine, devalue, marginalize, and even police the vantage point of the “lowly-other” along with all those who may seem different or idiosyncratic. Almost all Indian Reformers, in their earnest bid to reclaim lost civilizational and cultural “glory” made arbitrary distinctions between what they deemed “correct” and “incorrect” in Indian practices. This they did by adhering the practices to “lost-but-now-found” Shastras, plus tediously ridding them of influences that they considered aberrations caused due to “lower-instincts” of the commoners. The devadasi and the Hatha yogi in particular were direct casualties of such cleansing attempts to make Indian life “ideal” and “profound” once again.

What is important for us to register here is that this dream of the reformists was nothing new, it echoed the underlying drive of all “constructionists” who have through the ages been occupied in devising constructs to delineate and enforce the “ideal” upon the lived-life. The preoccupation of these constructionists, apart from the inculcation of “higher” and “refined” values has also been the “cultivation of innocence” and conformity among the common people, for the sake of their edification and upliftment out of the morass of their “lower instincts”.

Our ancient texts on aesthetics list things that may not be “shown” in literature or performance, the Sahitya Darpana, a 14th-century text by Vishvanatha Kaviraja lists a number of them, namely, battle, marriage, eating, cursing, death, amorous play, lying down, kissing, bathing, anointing to name a few. In nineteenth century, the Victorians in a bid to enforce stringent morality went as far as forming a décor-aesthetic, which was to drape the legs of chairs and tables. What is being controlled by such constructs are not the limbs of furniture but the suggestiveness of nakedness for fear of it exciting the lower instincts and triggering immoral thoughts and acts. So, it is a “suggestion” that is to be controlled; making both opacity and restraint the hallmarks of high or classical art and literature, and even interior design as we see in this example. Both of these, opacity and restraint, become woven into the pedagogy of the “classical” to stem out even the suggestion of that which might lead to the generation of ideas, images, mannerisms, and words considered unsavoury and immoral; and simultaneously to distance and police the other, i.e. the commoner, by attaching to them the derogatory “labels” of vulgar, low-life, common, cheap, even commercial and so on.

Chandraloka, a sixteenth-century text by Jaideva Piyushavarsha of Orissa, subdivides the term ashlila , i.e. vulgar, into three categories; these being vreeda , implying erotic acts that would embarrass or discomfit the modesty of the well-bred viewer or reader, jugupsa or disgust evoked by objects or acts considered abject and untouchable, and finally amangala, or things considered inauspicious such as death.

Rukmini Devi, the prime re-constructionist of Bharatanatyam dance categorically valorised bhakti, i.e. devotion over sringara, the amorous/erotic sentiment, both in her pedagogy and artistic works. For instance, freezing the movement of the hip, as it may suggest lasciviousness, became the hallmark of her style of Bharatanatyam taught at her institute, Kalakshetra. She painstakingly edited out the explicit verses of the traditional songs as well as the erotic gestures that were part of the devadasis’ repertoire as she considered them both vulgar and inappropriate for the use of the well-bred middle-classes; likewise, she rejected the devadasi-convention of biting the lower lip to depict the intensity of painful-pleasure; in the Mahabharata scene when Bhima slays Dushasana by tearing open his belly and pulling out his entrails, she did not subscribe to the Kathakali convention of pulling out a stream of red-dyed gauze hidden underneath the performer’s belt to enhance dramatic effect, as it seemed both excessive and violent to her; and in her choreography of the battle scene between Rama and Ravana in her epic-creation of the Ramayana, she chose not to depict the battle on the stage but had the dancing kinnaris or heavenly damsels describe the scene of blood and gore transpiring on the earth below from the skies above. I would say that she was not only following the dictate of the Shastras in making these decisions, but these were also her personal aesthetic choices informed by her taste, which to my mind remains unparalleled in refinement, her abhorrence for violence, as well as her idea of morality. I would also like to point to the fact that her aesthetic choices stay consistently shy of intense emotion and showing acts or mannerisms considered improper or abject.

I would now like to contrast these stipulations laid down by the Shastras and followed by not only Rukmini Devi but almost all reformers in every field and discipline through the late nineteenth and early-twentieth-century India, with the erotic poetry of Annamacharya (fifteenth-century) and Kshetraya (seventeenth-century). This Telegu poetry penned by men and sung by the pleasure women or devadasis is explicit both in its sexual as well as mercenary content. This poetry was the mainstay of the devadasi repertoire and its edited—by classical standards of restraint and opacity—version is still performed by Bharatanatyam dancers today in the form of padams, javalis and kirtanas.

Annamacharya, given the epithet of saint, writes suggestively about the woman’s body:

Don’t you know my house,

garland in the palace of the Love God,

where flowers cast their fragrance everywhere?

Don’t you know the house

hidden by tamarind trees,

in that narrow space marked by the two golden hills?

That’s where you lose your senses,

where the Love God hunts without fear.

And Kshetrayya continues in the same erotic vein:

You say, “Come close, my girl,”

and make love to me like a wild man, Muvva Gopala,

and as I get ready to move on top,

it’s morning already.!

And lastly, I cite an anonymous poem addressed to Lord Konkanesvara with bold sexual and mercenary content:

To sit by my side

and to put your hand

boldly inside my sari:

that will cost ten thousand.

And seventy thousand

will get you a touch

of my full round breasts.

Only if you have the money

Three crores to bring

your mouth close to mine,

touch my lips and

To hug me tight,

to touch my place of love,

and get to total union,

listen well,

you must bathe me

in a shower of gold.

But only if you have the money

So, what we have here are two well-documented sides of the stringent classicists-constructionists who advocated living by the book on the one hand, and the hereditary poet-performers on the other who freely wove their lived-histories and even their body’s “lowly instincts” into their art-making. Each is not only attractive in their own right but also equally repulsive to the other. Whereas the classicist vision may promise to fulfil our human dream of becoming restored, nay absorbed, unto a state of “untarnished-purity”; the sacred-erotic poetry emerging out of the abject-ethos of hereditary pleasure-women may offer a seamless experience of sensory-sublimity brought about through the distilled abstractions of their body, voice, tone, word, gesture, nuance, glance and style; and that too, within a safe-space tailor-made to un-normatively address the anxieties of intimacy and to unhesitatingly speak of things sexual in a manner and tone that may explicitly engage the body to lift the spirit of the rasika (aesthete) unto a buoyant-resolve where even the very possibility of intimacy may come into profound questioning. The truth perhaps is that both sides are in pursuit of the ever-nebulous middle ground, the madhyama avastha, where in the self may come into recognition.

However, the two sides remain ever mistrusting and severely judgmental of the other. While the former remains preoccupied with “textual-correctness”, the latter wrests the license and the capability to make and break their own rules in search of resonance; while the former holds deep-feeling in suspicion and even fear, the latter actively elicits a no-holds-barred engagement with the abjections of the body in search of a sensorially immersive poetic experience. We may have to concede that this conflict between the two is here is to stay, and the name-calling of the other is perhaps perennial in nature.

This name-calling based on mutual-repulsion brings forth corollaries befitting their perspectives around the flip-word “vulgar”. I have already listed the corollaries of the word vulgar from the distancing-sophisticate’s point of view at the beginning of this paper; from the perspective of the “distanced” or the one assigned to the margins, for whom knowledge may be derived not from the book but farmed out of the somatic intelligence and sensitivity of the body, it is the very “correctness” of the classicist-constructionist that is irksome. And from the margins this might appear to be too much of an idea, unbearably studied, image-conscious, un-lived, false, trite, literal, pedantic, didactic, flat, veneer, simulative, hollow, vapid, cheesy, appropriative, smug and so on. In other words, it might seem nothing short of a masquerade that apart from being fake and meaningless, may actually be defeating the very purpose of art, poetry, beauty, and resonance. A resonance that can only be born out of abstractions wherein the correct and the incorrect are freely allowed to co-mingle and disable the other.

To conclude I would like to say that it is of critical importance that in order to keep the middle-space of co-mingling alive, it is imperative to keep the space of the suppressed voice and the corollary-vocabularies of the distanced and marginalized alive and active. And even more important is to recognize the flip-sidedness of the name-calling words such as vulgar, because such words are powerful words, they are not only ploys for distancing, but can be vital tools to call out the bluffs of the other in order to challenge and tip the power-in equations for the purpose of opening a resonate space full of buoyant resolve. Because both within the subject and the object of the abject, there lies the promise of absence and sublimity.

Reference –

Ksåetrayya, When God Is A Customer: Telugu Courtesan Songs, Edited and Translated by – A.K. Ramanujan, Velcheru Narayana Rao and David Shulman, University Of California Press, 1994

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Navtej Singh Johar is a dancer-choreographer, scholar, yoga exponent, and a social activist. A recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi award for Contemporary Choreography (2014), his work—within all fields of his varied interests—remains consistently body-centric. It twines practice with critical theory and social action, traverses freely between the traditional and the contemporary, and rigorously engages both the philosophical and the sociological discourses of the body. His choreography draws on plural vocabularies: bharatanatyam, yoga, physical-theatre and somatics, and has won critical acclaim both nationally and internationally. A research fellow at the, International Research Centre, “Interweaving Performance Cultures”, Freie University, Berlin, Johar teaches Dance Studies at the Ashoka University, India. Founder-director of Studio Abhyas, New Delhi, a space devoted to refining the processes of embodied Indian practices as well as examining their historical contexts, Johar has devised two pedagogical methods, the BARPS method, designed to practice asana more effectively, and Abhyas Somatics, a practice that aims to evoke rasa and sukha that are essential to Indian aesthetics and Yoga respectively.

Of Witnessing and Vulgarity: Anxieties of the photograph of violence

In beginning to think about photographs today, one is compelled to ask – has the photographic image become inherently unknowable? Evading categorisation, the ‘medium’ of photography – if it can even be referred to as such anymore – commands ingenuity in the words and vocabularies we accord to it. As our collective and cultural experiences continue to be shaped not by events but by images of those events, we are finding ourselves in an ongoing series of confrontational encounters with the photographic. Occupying increasingly complex positions as spectators within rapidly growing networks of dissemination, it makes sense for us to question the knowability of the visual inundation of the ‘real’ through photographic encounters.

Our present moment is overwhelmed by visuals of violence, matched in their intensity by our anxiety to remain awake and indignant, investing in socio-political eloquence on what we are witnessing and so fervently trying to remember. Incorporating the extraordinary as well as the mundane within its ambit, this is a witnessing of a fragmentation that spans the collapse of the familiar, across public and private spheres of our lives. Agitating at the crossroads of visual transience, moral righteousness, convenient access and proliferation, this remembering grows more and more ungraspable in its multiplicity. It remains fuelled by the fleeting nature of public memory and outrage as well as the erasures sustained by the state of governance. The witnessing we undertake and submit to then – both collectively and individually – is layered and deeply situated in circuits of mass visibility and manufactured response.

In its most threadbare association, a photograph is a fallible record of a very specific encounter with a landscape. This errancy expands beyond its material existence, residing as well in the interpretative possibilities that surround it. It is undeniable that our preoccupation in the moment is to ensure remembrance in the face of undeterred violence, an endeavour assumed with great urgency. It is only fitting that our keenest mode of memorialising the affect of this flammability is the photographic. However, the photograph of violence has slipped into a dangerous rhetoric of appropriation that prescribes distant condemnation, avoiding any engaged transmission of trauma. This makes the production of affect in a photograph a perpetual entanglement of sorts – outsourced by medium, maker and subject through multiple acts of (dis)balancing that are drawn across orality, tactility and even haptic response. Even so, understanding the extent to which affect is embedded in our world of objects and social relations thus becomes a heavy burden for anyone to bear. But how does this come to intersect with our capacities as spectators to violent, murderous upheaval?

Marianne Hirsch in her seminal work on postmemory and the Holocaust writes of a rupture – a ‘radical interruption,’ – a before and after of ‘seeing’ a photograph of violence that is traceable in the generation that survived the Holocaust and also the generation that followed it. Though images of survivors, perpetrators and victims of the Holocaust number in the millions across state and national archives, Hirsch highlights an archival repetition in the inheritance of trauma that persists in the photographs that came to be emblematically identified with the event. Transformed into icons of the event in their material and memorial prominence, these symbols of a violent, traumatic past place at stake a ‘guardianship’ of the same. Examining what appears to be a contradictory logic in this obsessive repetition of the same set of photographs, she notes a duality in the afterlives of these images for the second generation. The most obvious result of such repetition was of course the cultivation of a banality in representations of the Holocaust, but at the same, this also stimulated a (re)production of affect that allowed for a transmission of inherited trauma in a way that it could be processed and redeployed in new contexts of reintegration and remembrance. This second generation – the postmemorial one, as Hirsch terms it – attempts to gauge a coexistence alongside these photographs of violence, while at the same time seeking new avenues to reenvision and redirect their persevering ‘mortifying gaze.’

Continuing along this route, one is led to wonder about the dynamics of our own contemporary witnessings. Catapulted beyond what was previously a limited understanding of its material existence, the contemporary photograph of violence now exists across modalities of repetition and surplus, where either volume is harnessed in and through virtual accessibility and multi-media that have possibly subsumed the outreach of print. Across genre and category, role and usage, the photograph of violence is expansive in its connotations, and more often than not, serves a variety of negotiations with manifestations of vulgarity. Keeping with the tone of critical speculation that occupies most of our waking hours, it becomes necessary to think about our processes of navigating the obscenities that occupy the intertwinings of subjecthood and gaze, immediate context and subsequent retelling.

Thinking aloud, Hirsch wonders if we are truly past our points of saturation as Susan Sontag initially posited with regard to seeing and internalising such images, or whether there is a actually a possibility for these photographs to maintain and disseminate an ethical, expansive remembrance in the aftermath of such violence. However, the specificity of our spectatorial condition could be understood as two-toned, encompassing a complicity in convenient silences but also a determined unwillingness to not let the resilience of our collectivity be co-opted by institutionalised, state-sponsored regimes and/or colonially narrow spaces of remembrance.

In ‘The Civil Contract of Photography,’ Ariella Azoulay demonstrates the role of photography as a key political instrument of emancipation in zones of conflict, focusing on the regions of Israel and Palestine. Observing the development of photographic practices in and around such zones, she theorizes the creation of conditions of inclusivity, responsibility and action outside of the regulatory surveillance of the governing state that have been catalysed by the political arena of visibility and reclamation enabled by photography. Grounded in a shared civic space of relations created by photography and its networks of circulation, Azoulay’s discussion of photographs of violence establishes the possibilities within meaning-making and remembrance to overturn what is seen and accepted within a frame.

Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie in ‘When Is a Photograph Worth a Thousand Words?’ writes of her encounters with the ethnographic Native American subject, documented as a stereotype, frozen in a foreign gaze and inside the ‘expert narrative’ of anthropology. She invites us to consider complexity in the ‘photographic sovereignty’ of a subject, receiving the gift of context as she does through an aboriginally-based, indigenous perspective. She cites philosophies and beliefs that she grounds in her Native culture, reiterating a non-conformity to allegedly ‘objective’ processes of observation that glorify, simplify and exoticise aboriginal uniqueness.

Photographs of violence that document the death and massacre of Native American spiritual leaders rarely coincide with evidentiary retellings that further reiterate the reality of the violence itself. She looks upon an image of the leader Big Foot killed at Wounded Knee, lying frozen in the snow – a photograph of violence, remembered through an archival veil of hopelessness. Reading perseverance into Native American spirit and the power of their survival, Tsinhnahjinnie’s chosen grammar of encountering such photographs of violence transgresses the realm of literal translatability that simplifies the deeply spiritual realities of Native American society. Taking her meaning-making to a space which is familiar to her – into dreams and their implicit meanings – she writes to evoke a specificity of indigenous religion and existence that shuns the seemingly rational readings of such acts of violence. Acknowledging callous misrecognition in the anthropological archive, Tsinhnahjinnie performs her space of remembrance outside of the delimits of isolation and imperial fixity, calling instead for the mutability of vocabularies in the reading of such photographs of violence.

However, the photograph of violence has slipped into a dangerous rhetoric of appropriation that prescribes distant condemnation, avoiding any engaged transmission of trauma. This makes the production of affect in a photograph a perpetual entanglement of sorts – outsourced by medium, maker and subject through multiple acts of (dis)balancing that are drawn across orality, tactility and even haptic response.

Drawing attention to the weapon-like violence of the apparatus, Teju Cole writes that in speaking of “shooting” with a camera, we are acknowledging the kinship of photography and violence. In combating the manipulations within the colonial, imperial gaze and its implications of the violence of extraction and erasure, we are urged to think of what remains in the aftermath of a photograph: possibly the vulgarity of audacity, of encoded yet unacknowledged power relations. To think outside this imperial understanding is, as Azoulay says, to “not let the photograph, a contingent product, overshadow the complex nature of the encounter out of which it was taken nor to blur the inequalities, the patterns of exploitation, and the incommensurable expectations, aspirations, and modalities of participation inherent in a photographic event.”

Is it possible then to envision a potentially adaptive vocabulary for the photographic, thinking of a ‘tendency’ instead of an arbitrary and absolute fixation on category? Our witnessing and its deployment of photography demands a willingness of words and meanings to accommodate fluid occupancies, hazards, possibilities and domains of the photographic image of violence in all of its unknowability today. Taking into cognizance the many historical trajectories of the photographic – its imperial and non-imperial potential – our present moment calls for a more intuitive stance towards it, inviting and identifying its fluid, evolving capacities and its conflations with a series of violence.