The Rambles of Fatigued Listening in 5¼ Movements

AUTHOR

Suvani Suri

Movement 1: The Burrow of Unsound

The air smells pungent and arid. Fatigue traverses and slowly fills up the site of what once was a burrow, now turned outside-in. Heavy and dazed eyelids gaze at the last remaining parts of the immaculately constructed stone walls, hearkening back to that moment when a faint whistle first slithered into the labyrinthine passages of the burrow. The crumbling walls are starting to heave and sigh, occasional rumbles giving way to a steadier, humid rhythm spreading all the way through the cracks of the floor into the pulsating pores of the skin.

The story of Kafka’s Burrow1 is one that brought me to uncanny sounding and resounding. It is a tale of anxious listening. A nameless and undefined creature inhabits the story. It is most likely a mole or a badger, going by the signs that lie scantily strewn across the volume of a convoluted underground fortress. A register of hyper-listening is invoked by a piercing sound that hears the mole, even before it feeds into the signal at the edge of sleep and wakefulness. Like an earworm, the “inaudible whistling”2 wriggles its way from the depths of the mole’s interiorities all the way into its aural faculties. From an inside to an outside, from refuge to peril, it spirals all the way through the wormhole into the extimate. Driven to the edge by the task of locating the source of this acousmatic sound, the mole steadily enters into a state of neurotic surveillance3, a sousveillance. The whistle is writing the mole as it keeps looping into a feedback of its own making, eventually demolishing the burrow. In a bid to excavate its way out of the clutches of the disconcerting unsound, a circuitous route is taken by the mole towards what seems at first like an urgent escape but then it homes in on the task of identifying the bug. Scuttering up to the thresholds of an erstwhile burrow, now dizzy with exhaustion and yet not being able to metabolise the inexhaustible ringing, this marks the first retreat. A retreat into the orbit of the dislocated voice overflowing with weird echoes that brush against the undulating surfaces of a future anterior and bounce back into the unhomely present.

Movement 2: Anxious Listening

There’s a peculiar anxiety that I experienced when encountering the archive of the Linguistic Survey of India (LSI)4. An acute sensation that I often relate to a contingent tryst with spaces, situations, scenes and worlds that feel oddly familiar, while being complete strangers. The split felt within a fleeting moment, when strangeness exudes an uncanny intimacy and pulls one into the necessity of tuning into frequencies other than of one’s own, an inside-out.

The LSI was an ambitious colonial project, headed by George A. Grierson and conceived with an administratorial intent. It produced a massive collection of voices, sounds, and utterances in various languages and dialects captured from all across the Indian subcontinent in the years from 1914 to 1928. It bloated and bulged in all directions to contain abundant histories in the form of songs, ballads, stories, and polyvocalities. In my second attempt to retreat from the burrow, I fell through the cracks and cavities of the phonographic recordings.

All in all, the LSI audio archive is filled to the brim with the weight of listening. It interlocks with the anxieties of the monarch in Italo Calvino’s A King Listens5, who is so consumed with the paranoia of revolt by his subjects that he wants to (over)hear every single acoustic signal in the burrow of his castle. One day, his excessive listening is interrupted by a singing voice. In a similar manner, Griersom dreamt of the expansion of the empire, fuelled by the hunger for ears that could hear, interpret and anticipate every language that was ever spoken in the subcontinent. The coloniser’s body is covered with sinuous horns that perform acts of auditory espionage and extraction. An excess of hearing that bores deep into the systematised and structural languages of caste, class, race, and borders, to extract, swallow, fortify and accumulate. A hungry listening.6

Movement 3: Hypnagogia

A curious high-pitched buzzing could be heard from afar as I slipped into a light stupor. The burrow is a dream. In the state of hypnagogia, all I could hear was the rising anxiety of the mole. I sensed the swelling panic of the creature, scurrying around, trying to locate the source of the sound with its own pulse. The burrow of the archive, the archive within the burrow.

The shimmering whistle would continue to float in my ambit for days to come, at times ebbing from my feet and trailing behind wherever I went, at other times causing me to stumble, then flying away into the distance and peeking at me from behind one of the nooks of Castle Keep7. What does this acousmatic sound gaze at, so piercingly? The arrhythmic throb of a metronome breaks the syncopation of anxious fatigue. It got foggier and denser in the archive, until I heard the colossal sigh. The third retreat in which I fall out of my slumber.

The sigh felt like a deep cut, an edge which opened into the vast continuity of a hypnagogic state of listening. This is a state adrift between an alert inertness and a wobbly state of ludic awake-ness. The uncanny resonances of fatigued histories– an association of bodies and voices that constituted the archive of the LSI– pulsated with the anxiety of an encounter with the unfamiliar yet known that overwhelmed me. Is it that the listener is like a tapehead activating the record of archived languages in/of bodies or is the shellac record dreaming up the listener with every spin, with truths emerging at the slippages of captured bodies and languages?

Fatigue can produce certain conditions of listening that emerge from within the repetition of its strain. A litany of movements stretches infinitely and suspends the fatigue until it descends into a thick cloud upon which one is afloat and listening. It’s something other than the white noise machines that induce sleep. Neither does it come in shades of pink, black or blue. Perhaps it is closest to a periwinkle noise. A misty buzz that, on one hand, bypasses the state of hyper-vigilance and on the other, steers clear of slinking into a snug hypo-alertness akin to passivity or numbness. Rather it has this angular frequency that produces a parallax and drifts into the subterranean acuity of listening. A double movement of fatigue contains the possibility of tuning out of the regime of calibrated time and mastery into the realm of real and finite instances. This earmarks the composition of a score that falls outside of the ceaseless conveyor belt of real-time.

Movement 4: Muzac

A movement in two instances.

I. The Miner’s Ear

In her essay ‘The Miner’s Ear’, Rosalind Morris invokes the image of the mole and the burrow via Vilakazi’s poem that recites/ resides in the suffocating space between the sounds of the mining machines and the eventual bodily breakdown.8

An excerpt from Vilakazi’s poem (as cited in the essay) that ventures into a mythological narrativisation of the mines-

“one day a siren screeched

And then a black rock-rabbit came,

A poor dazed thing with clouded mind;

They caught it, changed it to a mole:

It burrowed, and I saw the gold…” 9

Rosalind Morries writes– “The whites, observes Vilakazi, were rendered stone by the love of gold, devoid of human affect in their holes, as the (black) moles sent down were reduced to an animal status through the murderous magic of displacement and wage labor.”10

II. The Worker’s Clap

Gene Autry’s 1942 hit ‘Deep in the Heart of Texas’ somehow earwormed its way into the Muzac Inc. playlist for factory workers. These were hours of bespoke playlists designed to keep playing and to control the pace of productivity with their invisible rhythms. This song punctured the assembly line with a resounding clap in its bassline. The factory fell into chaos as all workers paused the operations to clap hands in time with the song’s chorus. The Muzac company’s president later acknowledged, “Once people start listening, they stop working”.11

Etymologically ‘Fatigue’ can be traced to the latin phrase ad fatim— a sense of satiety or a surfeit. In other words, a satisfaction produced via an excess of indulgence. How could a fatigued listening hijack the phantasmagoria of a sensorial excess produced in a system or a structural assemblage? What could it tear up into? A clap. A sigh. A whistle. A scream?

The scream is a curious object of sound, its appearance almost like a sharp cut, an abrupt opening, a counterpoint, an overture, an insertion, an irruption. An ear-splitting scream. The splitting into two is of the time before the scream and the time that becomes of it. A scream is not a yell, it isn’t a shout, it isn’t a shriek. It isn’t also a cry or a howl. A scream is a strange one. It could be bits and parts, sections and wholes of all of these and yet not be like any of these. Its uncountable effects and pulsations signify a material diffusion into an immaterial whole.

I would like to scream but have always found myself unable to. The most I can manage is a shout, a holler, a yell perhaps. I would like to write a scream as the fourth movement towards burrowing into the archive of unsound. It hides in one of the grooves of a record, adjacent to the sigh.

Movement 5: Drifting

The blurs and fragments of the Parable of the Prodigal Son, translated to Urdu and performatively narrated by Baqir Ali in Recording No. 6825 AK12 unfold into this immense sonic landscape of labour. It is an uneasy and breathless topography bubbling with the rhythm of precise renditions, only to be broken by glimpses of contingent utterances.

The dizzying and continuous repetition of the record doesn’t let you hear it until the scratch on its surface meets the fatigued ear. And then one catches it all in a flash as the inexhaustible sigh spills out. Within the crackle and glitches of recorded sound, the exhalation keeps open the discrete aperture in the voice, if only momently.

I often go on these drifts and nibble away at the voices in the air. Is there a name for the dislocation experienced when the sound of a language feels like home and yet resists comprehension? The traces and residues produce a shaky distance which then gets traversed by a scattered listening. What if one is to sing a song yet to be written in the voice of Hassaina or Baqir Ali? A mellifluous refrain that transmits earworms into the years of a future past. They chew on the knots in the archive, breaking it down and releasing more metabolic agents into its burrows. What we have is a ((k)not)archive, that preserves the inaudible duration conjured by each recorded voice at the precipice of sound and unsound.

“All grooved disc media is susceptible to warpage, breakage, groove wear, and surface contamination. Types of surface contamination include: dirt, dust, mould, and other foreign materials, all of which can abrade or damage the grooves and diminish playback sound quality. Excessive surface damage and groove wear are generally identifiable on discs that have a dull surface, scratches, pits, and/or cracks.”13

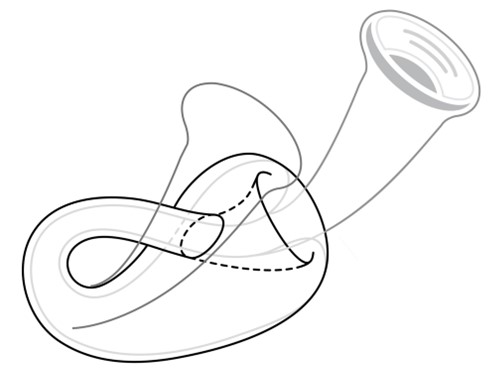

Movement 0 or 5¼ : The Klein Horn

A counter-movement back to the acoustical unconscious of the disc(s). The symptomatic appearances of the scratches and freckles on its surface. Every time it is played, the gashes produce a new sonorous topography and an infinite listening that does not seek but emerges from within the punctures of an abyss.

A macro-zoom into the grooves of the shellac discs containing the constellation(s) of voices, reveals an uncanny resemblance to the inside of a mouth. The gentle curves, undulating surfaces, and palatine folds make room for and generate the conditions for seismic shifts, as the listening body approaches. Palate Tectonics, the theory of geotrauma processed as thoracic impulses and speech acts, proposed by DC Barker14, hearkens back to the rumbles of a past and the futurity of tectonic sounding produced by fatigued listening.

The fifth and a quarter of a movement takes place in the minor occurrence of a sigh. It is carried alongside the light tremors in speech, a stuttering breath, sporadic pulsations and weary strains of the vocal cords. Radiating from an oneiric epicentre, the vibrations invert and scrape out the historical discontinuities occurring across fatigued landscapes beyond merely the geological, anatomical or biopolitical.

Shaped like a trumpet, the winding rooms in the burrow of Grierson’s archive are now infected and laden with a deep and reverberant sigh. The sticky sigh holds a desire to whisper outside of the register of what the phonograph can hear. The air smells pungent and arid.

ENDNOTES

- Kafka, Franz, “The Burrow.” 1992. In The Complete Short Stories of Franz Kafka, edited by Nahum N. Glatzer. Translated by Willa and Edwin Muir, Tania and James Stern. 325-359. London: Vintage.

- Ibid.

- Schuster, Aaron. “Enjoy Your Security: On Kafka’s “The Burrow” – Journal #113 November 2020.” e-flux. Accessed October 14, 2022. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/113/359952/enjoy-your-security-on-kafka-s-the-burrow/.

- Grierson, George A. 1903-1928. “Linguistic Survey of India.” The Digital South Asia Library. https://dsal.uchicago.edu/books/lsi/.

- Calvino, Italo. 2009. Under the Jaguar Sun. Translated by William Weaver. London: Penguin Books, Limited.

- The phrase ‘Hungry Listening’ has been formulated by Dylan Robinson in his evaluation of settler colonial listening modes and perceptions. (Robinson, Dylan. 2020. Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.)

- Castle Keep, in Kafka’s story, is a secret retreat- a burrow within the burrow- which the mole has arduously constructed for safekeeping its stores

- Morris, Rosalind C. “The Miner’s Ear.” Transition, no. 98 (2008): 96–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20204249.

- As cited in Morris, Rosalind C. “The Miner’s Ear.” Transition, no. 98 (2008): 96–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20204249.

- Ibid.

- Blecha, Peter. 2012. “Muzak, Inc. — Originators of “Elevator Music”.” HistoryLink.org. https://www.historylink.org/File/10072.

- Recording No. 6825 AK, Digital archives, Linguistic Survey of India, Gramophone Co.,Calcutta, Europeana sounds, National Library of France, public domain. https://www.europeana.eu/en/item/2059219/data_sounds_ark__12148_cb41483352r

- “PSAP Phonograph Record.” Preservation Self-Assessment Program. Accessed September 8, 2022. https://psap.library.illinois.edu/collection-id-guide/phonodisc.

- Moynihan, Thomas, “TH1. Barker Spoke.” 2019. In Spinal Catastrophism: A Secret History, 57-74. London, United Kingdom: Urbanomic.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Suvani Suri is an artist based in New Delhi. She works with sound, text and intermedia assemblages and has been exploring various modes of transmission such as podcasts, auditory texts, sonic environments, objects, installations, fictions, experimental workshops and live interventions. Her research interests lie in the relational and speculative capacities of listening, voice, aural/oral histories and the spectral dispositions of sound that can activate critical imaginations. Actively engaged in thinking through the techno-politics that listening is embedded in, her practice is informed by the processes of production, mediation, perception and distribution of sound. Alongside, she composes sound for video and performance works and teaches at several universities and educational spaces where her pedagogical interests conflate with a sustained inquiry into the digital and sonic sensorium.

Sound from the Ground: Pre-modern Sonic Practices in India

AUTHOR

Budhaditya Chattopadhyay

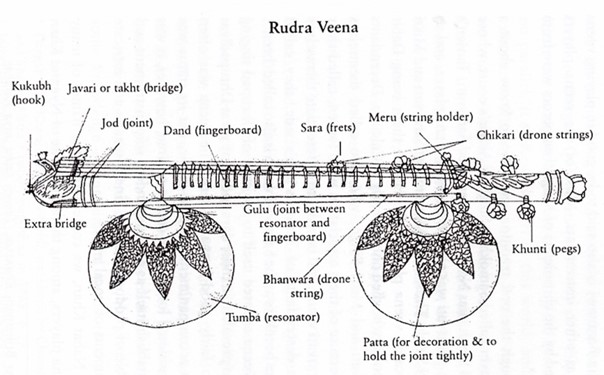

A pluck of the strings in the lower registers of the Rudraveena or the Tanpura produces sounds that are as plurivocal and multi-harmonic as the sounds of natural phenomena, such as thunder or rains, or heavy wind through the fields, representing a textural complexity and sonic saturation that are grounded and embedded in nature. The resonant grains in the sounds from the strings of these pre-modern instruments are often deemed desirable in traditional sound performances like Dhrupad and Khayal, to provide a situated and grounded sound, as close to natural temporality and spatiality as possible. I have shown in my earlier research (2021a, 2021b, 2022) how Ragas are reflections of natural temporalities: each Raga dedicated to a time of the day; for instance, Darbari is for midnight, and Bhairavi for early morning. The court music and devotional music-oriented instruments such as Surbahar and Nadaswaram are accommodative of intricate and often complex tonal formations. The outdoor and communal instruments like Ektara or a folk percussion instrument like Madal are also meticulously designed to produce sounds close to the ground. As sound-producing technologies and machines, these instruments have gone through innovative design developments and tunings as musicologists like Alain Daniélou have suggested (1995). As situated technologies, these instruments explicitly use natural materials. The Rudraveena‘s body is a tube made of bamboo or teak trunk attached to two large tumba resonators made from gourds. These pre-colonial, pre-modern sound-producing instruments and interfaces were conceived of and built in South Asia using indigenous technologies and pre-modern methods, in ways that destabilized the nature-society binary, contrary to the methods of European modernity. French philosopher Bruno Latour has argued (1993) that pre-modern communities made no distinctions between nature and society, while Western modernity was based on this exploitative dualism.

In the seminal treatise Natyashastra (c. 200 BC – 200 AD), Indian aesthetician Bharata discusses the uses of various sound instruments, proposing a four-fold classification of these sound-reproduction systems: tat (strings), ghan (solid), sushir (winds), and avanaddh (covered membrane). This was a systematic attempt to taxonomise sound technologies based on the type of sound-producing material, such as strings, solid body, air column, or stretched membrane, which are made to vibrate using different techniques of interfacing such as plucking, blowing, bowing, and striking. In the 1920s, the Indian physicist Dr. C. V. Raman conducted research to uncover the unique acoustic properties of Indian string and percussion instruments and the intricate technological innovations behind making them. Raman scientifically proved that the materials and techniques used in making as well as performing on these instruments result in microtonal and timbral qualities that are unique and not found in the musical instruments of the West. The custom-made curvatures of the bridge that supports the strings, and the tensile, vibrating membrane in percussive instruments like the Madal, the Dholak, and the Dhak were significant technological contributions that India made to the world of sounds. Contemporary Music Retrieval System scholars, such as Matthias Demoucron, Stephanie Weisser, and Marc Leman identify how Indian traditional sound-producing instruments are characterised by the presence of the sympathetic multiple string clusters called taraf and the curved wide bridge called jawari (often reinforced by a cotton thread), underlining the ways in which these intricate and sophisticated innovations make the sounds of Indian traditional music uniquely complex, embedded in nature, and grounded in the philosophy of multiplicity. They are beyond the analytical comprehension of today’s simpler computational algorithms based on Western equal-temperament tuning systems. This knowledge ecosystem was transmitted orally from generations to generations resulting, in multiple schools of thought and performative interpretations, and yielding agency for the many performers.

However, such non-Western sound technologies and embedded practices were often deemed “primitive,” and termed “indigenous” in the same vein as “pre-modern,” by the dominant Eurocentric sound and music culture that bore the colonial perspective of a provincial sense of superiority. Media scholar Marshal McLuhan’s seminal admission of oral systems as “primitive” is one such reflection of this colonial attitude. The invocation of the pre-modern as an inadequately developed opposition to the modern, however, is widely condemned today as European modernity’s representation of its Other. Scholars like David Mosse and Esha Shah have shown how the currency ascribed to the idea of the pre-modern (or what is otherwise loosely termed “traditional”, “primitive”, or “indigenous”) is not only founded on a binary opposition with the modern but also embedded in particular strategies of imagining a pre-colonial “primeval” past and the lived globalised present from a Eurocentric perspective, and therefore, putting in place a power structure in which modern technologies are posed as superior and capable of saving the world. These colonially positioned perceptions and views are far from being historically accurate. The usage of the prefix “pre” before “modern” should not suggest that modernity starts from a distinct temporal point and that everything prior was primitive: this, in fact, is a grossly colonial perspective that upholds Western dominance and supremacy. South Asia, particularly the Indian subcontinent, housed sophisticated sound technologies, which is evident in pre-modern musical instruments such as the Rudraveena, the Surbahar, the Nadaswaram, and the Yaazh, among others, the tuning systems of the temple bells, North-East Indian wind chimes, and performative sonic accompaniments like Ghunghroo. All of these, and so many more, embody the handling of complex sonorities with innovative instrument design and tunings.

Given a more egalitarian and equitable shift in the medial perspective now, one may ponder upon the archaeology of what is commonly understood as “technology” – which is often a Western concept of linear progression, and, in essence, instrumentalised as a colonial tool of surveillance, and plunder. Indeed, if we take a historical perspective, in South Asia, the transfer and transmission of modern technologies took place as a colonialist and imperialist strategy of control, that would enable the exploitative inventorisation and governance of local resources. In India, the advent of such technological manifestations, such as railways and factories, happened through colonial models of development and profit-making that went on to primarily benefit the Raj. Western media technologies, such as recording, photography, radio, and cinema, all contributed to these administrative systems. It was only the colonial subjects who gradually hacked into these technologies and reclaimed them to produce new hybrid kinds of aesthetic practices. Of course, the Global North’s condescending approach towards the colonised South didn’t allow for an equal distribution of power, knowledge, and aesthetic understanding. That is why pre-modern sonic practices from India, like many such rich practices outside of Europe, are not considered part of the canon in the process of making a taxonomy of what is termed “tech arts”, “media arts” or “sound art” in the West. However, India has been home to some of the oldest and most time-tested technologies and practices in the visual, literary, and sonic realms, as well as in urban design, water management, and agriculture. There would be no justification for a hierarchy of knowledge systems and cultures if we listened to pre-modern and pre-colonial aesthetic practices where a pre-modernisation concept of technology existed with a grounded, community-driven and embedded vision, which was as intricate as its global counterparts, though largely ignored in Western histories of science and technology. Musical instruments are some of the most prominent examples of these technological innovations. If we unpack the dexterity with which sound-producing instruments were built in India using home-grown technologies of tuning and design, we will find that pre-modern technologies and sonic practices were as sophisticated as the technology we know today from a Western colonialist standpoint. Therefore, it makes no sense to adhere to the hierarchy of “high tech” and “low tech” which conflates the pre-modern with the primitive and to define creative practices only from a Western taxonomy of sound and media arts. Given these historical examples of artistic practices and innovations from India’s pre-modern past, sound art needs to be redefined with an aim to decolonise sonic practices, giving due credit to artists and artisans from the Global South.

NOTES

Chattopadhyay, Budhaditya (2022). Sound Practices in the Global South: Co-listening to Resounding Plurilogues. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chattopadhyay, Budhaditya (2021a). “Uncolonising Early Sound Recordings”. The Journal of Media Art Study and Theory Vol. 2, No. 2 (Special Issue: Sound, Colonialism, and Power).

Chattopadhyay, Budhaditya (2021b). “Unrecording Nature”, in Kuljuntausta, Petri (ed.), Sound, Art, and Climate Change. Helsinki: Frequency Association.

Daniélou, Alain (1995). Music and the Power of Sound: The Influence of Tuning and Interval on Consciousness. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions.

Mosse, David (1997). “The symbolic making of a common property resource: History, ecology and locality in a tank-irrigated landscape in South India”. Development and Change 28(3): 467-504.

Mosse, David (1999). “Colonial and contemporary ideologies of community management: The case of tank irrigation development in South India”. Modern Asian Studies 33(2): 303-338.

Demoucron, Matthias; Weisser, Stephani; and Leman, Marc (2012). “Sculpting the Sound. Timbre-Shapers in Classical Hindustani Chordophones”, in Proceedings of the 2nd CompMusic Workshop (Istanbul, Turkey, July 12-13).

Latour, Bruno (1993). We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Shah, Esha (2012). “Seeing like a subaltern – Historical ethnography of pre-modern and modern tank irrigation technology in Karnataka, India”. Water Alternatives 5(2): 507-538

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Budhaditya Chattopadhyay is a contemporary artist, media practitioner, researcher, and writer. Incorporating diverse media, creative technologies and research, Chattopadhyay produces works for large-scale installation and live performance addressing contemporary issues of environment and ecology, migration, race and decoloniality. Chattopadhyay has received numerous residencies, fellowships, and international awards. His sound works have been widely exhibited, performed, or presented across the globe. Chattopadhyay has an expansive body of scholarly publications in the areas of media art history, theory and aesthetics, cinema, and sound studies in leading peer-reviewed journals. He is the author of four books, The Nomadic Listener (2020), The Auditory Setting (2021), Between the Headphones (2021), and Sound Practices in the Global South (2022). Chattopadhyay holds a PhD in Artistic Research and Sound Studies from the Academy of Creative and Performing Arts, Leiden University, and a Master of Arts in New Media from the Faculty of Arts, Aarhus University. Chattopadhyay is currently a Visiting Professor at the Academy of Art and Design, Basel.

https://budhaditya.org/

Ṣadā: Her-story and Echoes of Nationhood

AUTHOR

Shweta Sachdeva Jha

fazā ye amn-o-amāñ kī sadā rakheñ qaa.em

suno ye farz tumhārā bhī hai hamārā bhī —Nusrat Mehdi1

To protect the peace around us forever,

Listen, this is our duty, both yours and mine.

This year, India completes 75 years of independence as a nation-state, while our perception of our nation-scape/nationhood becomes increasingly fractured and polarised. Women are in positions of power as well as agents of protest2 but where do they figure in our recollections of our past? And can that past be audible? This essay is a woman educator’s self-conscious response as she listens to a contemporary poetess and her she’r.

The Urdu word sadā can be written in two different ways although, when spoken, they sound the same;

سدا (Sadā) means ‘always’

صدا (Ṣadā) is ‘echo or call’

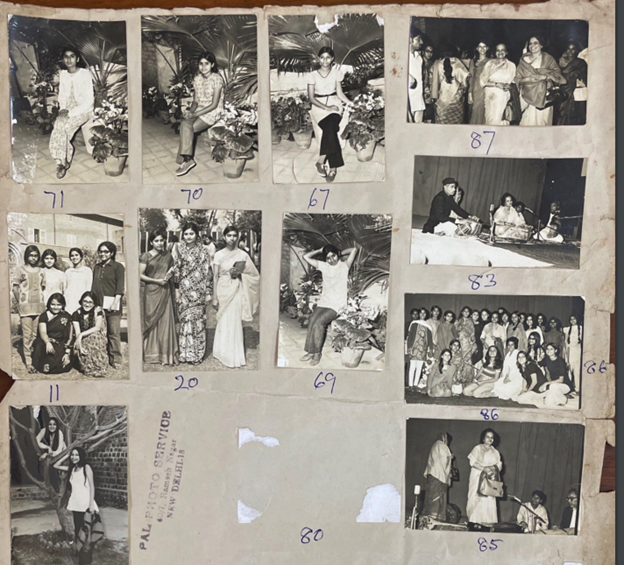

Moving from the first interpretation used by Mehdi to the second one, in this essay, let us listen to the echoes/calls of or by women in the past. I teach in Miranda House, a women’s college in the University of Delhi and I have spent the past few years pondering over college-going women’s archives and histories.3 Starting as a personal project and then growing into a collective, we have been documenting experiences of college-going women through their writings, photographs, and oral histories (via recordings) since 2019. A microcosm within the soundscape of the nation, Miranda House was founded in 1948.

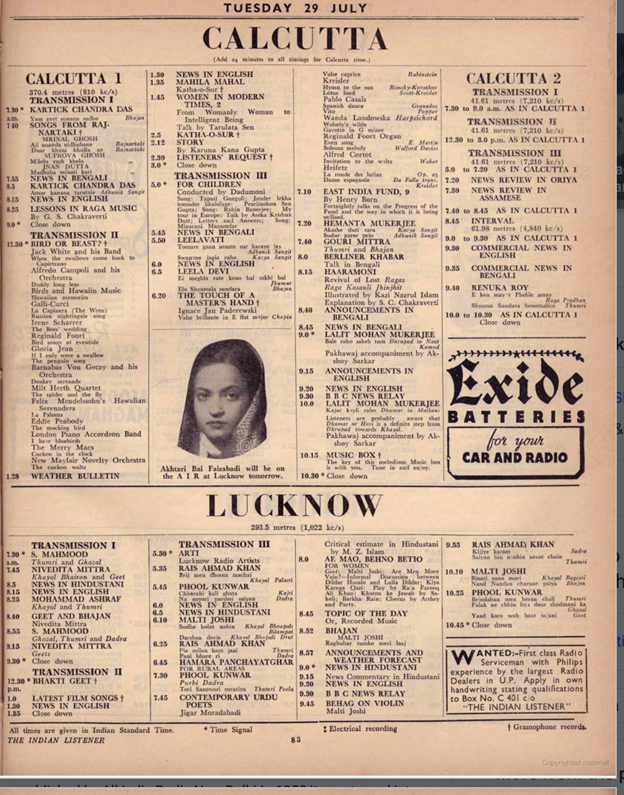

While young women thronged to colleges for higher education, Lata Mangeshkar’s (1929-2022) voice enthralled the audience of Hindi cinema in films such as Andaz, Mahal, and Barsaat in 1949. She ‘not only embodied the nation but sang the nation’.4 At the same time the strains of the soulful ghazals of Begum Akhtar (1914-1974) were audible on the All India Radio the same year. Initially known as Akhtari Bai Faizabadi, she had performed on stage and in films as a famous tawa’if singer5 earlier. But her marriage to Ishtiaq Ahmed Abbasi in 1945 meant she was no longer free to perform. In 1949, Begum Akhtar finally returned to the sound waves. She was the ‘Queen of Ghazals’ while Mangeshkar became the ‘Queen of Melody’. With the backdrop of the Indo-China War hanging over the Republic Day Celebrations in 1963, Mangeshkar’s rendition of ‘Ai mere watan ke logon’ would ultimately mark her indelible presence in the sonic history of our nation-scape.6 But how did women respond to these singers?

Begum Akhtar had performed at Miranda House on 7th March 1974, the 26th founder’s day of the college when many young women listened to her in rapt attention and awe. Although musical knowledge and tradition are often assumed to be patrilineal and gharana-centric, women like Akhtar had women shagirds (student/disciple)).7 Rekha Surya, an alumna of the college, had become her student in 1972. Akhtar passed away in October 1974 but an interview recorded in 2021 revealed the fondness with which a shagird recalled her guru and the unique experience of having memories and musical knowledge be shared and passed on between women.8

Beyond music and recording artists, listening to women’s memories or building sonic archives can deepen and interrogate our understanding of nationhood in ways that written texts often cannot.9 A fascinating instance of how listening unravels the gendered soundscape of our past lies in the life-history of Usha Mehta (25 March 1920 – 11 August 2000) and the case of the secret Congress Radio.

The story of the soft-spoken Usha Ben (‘ben’ for sister), a young girl of 22 in 1942, has now been published by her former student, Usha Thakkar, who compiled it from conversations and texts. Both these women later retired as academics from the SNDT Women’s University, Mumbai, again reminding us of how women’s colleges are significant though neglected sites of shared memories and sound histories.10

Responding to Gandhi’s call for the Quit India Movement in the year 1942, a group of young men and women, including Usha Ben or Radio Ben as she would be called later, initiated the idea of a radio station and a transmitter. Their efforts led to the Congress Broadcasting Station with its own transmitter, transmitting station, signal, and distinct wavelength. The broadcast went on air at 8.45 PM and was announced by the Bombay Congress Bulletin on 3rd September 1942. These programmes were a nightly event broadcasted from Bombay at 42.3 metres’ wavelength, though Radio Ben announced that they were speaking ‘somewhere from India’. Morning programmes and recordings of ‘Hindustan Hamara’ and ‘Vande Mataram’ were played on the radio. This continued till 12th November 1942 when the station was seized in operation by the British and the team arrested. Usha Ben was imprisoned for 4 years. The radio had been a major means of communication during the Second World War11, but Usha Ben forged our anti-colonial nationhood upon the anvil of the radio and made it a medium of protest.

Interview with Usha Mehta, posted on August 2017

Courtesy: The Press Information Bureau, Government of India

On the eve of Independence in 1947, Saeeda Bano started broadcasting with All India Radio in Delhi and became the first woman Urdu newsreader during the turbulent time of freedom and Partition. Bano’s immaculate Urdu diction made its way through the airwaves and into the homes of the newly minted citizens of Independent India.12 She was one of the many women broadcasters all over the world, a sonic marker of the women’s movement and feminist struggle in the twentieth century.13 Across the newly carved borders of the Indian subcontinent, the soundscape was shaped by women newsreaders, announcers, singers, broadcasters, and performers at radio stations in Lahore, Jalandhar, Lucknow, Madras, Delhi, Mumbai and many other cities and towns.14 Begum Akhtar, Usha Mehta, Saeeda Bano and Lata Mangeshkar belong to a long lineage of women who deftly used sound technologies to shape the sounds of a fledgling nation.

To trace this diverse lineage of sonic interventions by women, we need to shift our focus from sound-production and broadcasting to include listening practices. As we get inundated by multimodal content, the diversity of women and our pasts will become audible15 only if we turn into nuanced and discerning listeners and archivists of memories. Beyond the raucous noise of an enforced, singular nationhood lies a mellifluous, lyrical, and robust sonic past shaped by myriads of women if only we would listen.16

NOTES

- Her poetry can be followed at https://www.rekhta.org/couplets/fazaa-ye-amn-o-amaan-kii-sadaa-rakhen-qaaem-nusrat-mehdi-couplets

- Currently there are 11 women in the Cabinet Ministry and our President now is an Adivasi woman, at the same time throughout anti-CAA Protests, Sabrimala Temple Entry, Hijab controversy in Karnataka schools, women have been fighting against oppression.

- https://mirandahousearchive.in/. I gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr Avabai Wadia and Dr Khurshedji Wadia Archives for Women Fellowship (2020) to start the project. I lead the Miranda House Archiving Project team and it was started in 2019. Initially a personal project it has now become a collective team of teachers, non-teaching men and women, students and alumni. For more see the website.

- Vinay Lal, ‘Singing the Nation’ Open Magazine, 11 February 2022. https://openthemagazine.com/cover-stories/singing-the-nation/

- The history and contribution of tawa’if singers as recording artists is richly documented now both through textual and audible resources. See https://ignca.gov.in/Begum_Akhtar/index.html For more on Vidya Shah’s project on women recording artists see https://ncaa.gov.in/repository/search/displaySearchRecordPreview/IGNCA-AC_1382-AC/Lecture-on-Women-on-Record-Contribution-in-Music-(Vol.-I)

- Lal, Singing the Nation.

- Shanti Hiranand, Begum Akhtar: The Story of my Ammi (Viva Books, 2005).

- Oral History transcript, online interview of Dr Rekha Surya taken by Gayatri Punj, Devika Gupta 18 February, 2021, pp. 1-2 (Miranda House Archiving Project).

- For use of oral history see Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India (Penguin Random House, 2017).

- I am grateful to the MHAP intern Jaya Narayan for informing me about Usha Mehta. Usha Thakkar, Congress Radio: Usha Mehta and the Underground Radio Station of 1942 (India Viking, 2021).

- In May 1940 the All India Radio had done listener based research in five major cities across 13, 507 listeners and found that more Indians were using the radio to listen to news hostile to Britain. Ibid.

- Saeeda Bano, Off the Beaten Track: The Story of My Unconventional Life trans. Shahana Raza (Zubaan and Penguin Books, 2020).

- See Christine Ehrick, ‘Radio and the Gendered Soundscape’, in Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay, 1930–1950, Cambridge University Press, 2015 pp. iii -iv.

- Begum Akthar was often called Akhtari Bai too. The radio magazine published by AIR is a great source to see how women singers like Akhtar performed so often on the radio for different stations. For example see The Indian Listener (April 21, 1957 pgs. 13, 20, 27, 39, 41, 44) https://worldradiohistory.com/INTERNATIONAL/Indian-Listener/50s/The-Indian-Listener-1957-21-04-1957.pdf

- Sound is the basis of our foundational knowledge and modernity is linked with sound as it becomes commodified and measured. See Jonathan Sterne, The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 2-3.

- I am thankful to my student Akshika Goel for her comments on this piece.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shweta Sachdeva Jha teaches English at Miranda House, University of Delhi. She won the Felix Scholarship to study for a PhD at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Her interdisciplinary interests range across women’s history, children’s picture books, Urdu popular literature, and digital archives. Parts of her thesis on the tawa’if have been published as chapters in Speaking of the Self: Gender, Performance and Autobiography in South Asia (Duke University Press, 2015) and The Bollywood Islamicate: Idioms, Histories and Imaginaries (Orient Blackswan, 2022). Her chapters on women’s writing in Urdu can be read in South Asian Gothic: Haunted Cultures, Histories and Media (University of Wales Press, 2021) and Sultana’s Sisters: Gender, Genres, and Genealogy in South Asian Muslim Women’s Fiction (Routledge, 2021). Her awards include the Avabai Wadia Fellowship by SNDT University of Women, Mumbai (2020) and the Tata Trusts-Partition Archive Research Grant (2021).

A Symphony Found in the Wilderness of Noise

AUTHOR

Padmanabhan

“No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” – Heraclitus.

The first recorded sound is only 165 years old, a cacophony of echoes recorded by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville on a phonautogram. The temporal nature of sound demands that it commit sonic suicide with the ebb of time, leaving no trace of its presence, no material or visual remains. Thus, the archaeology of sound is heavily reliant on the visual description of past experiences and a conscious effort of our auditory perception to reimagine the (lost) aural reality. However, drawing upon Heraclitus, we can say that no man ever hears the same sound twice, meaning we must bear in mind that despite our best efforts to find the right note, we are often left with vague harmonies to make sense of.

“There is geometry in the humming of the strings. There is music in the spacing of the spheres.” – Pythagoras.

Music of Spheres

The history of soundscapes pre-dates the formation of planet Earth and goes back to the very dawn of Time in this universe: the Big Bang, prior to which, one could reasonably imagine, silence prevailed. It was an event that not only gave birth to billions of planets and galaxies over time but also created an ever-present cosmic composition that was inaudible to human ears until very recently.

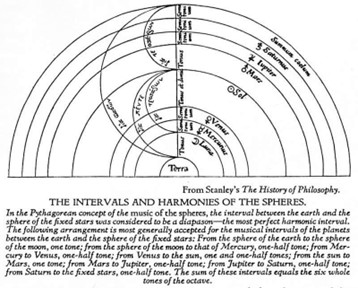

The geocentric dance of the celestial bodies spacing themselves at relative distances from each other and from the Earth, mirrors that of tones and semitones forming chords and scales. This observation led the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras to believe in the existence of divine harmony. This symphony of the cosmos was first proposed philosophically in his Musica Universalis, or Music of Spheres, and he arrived at this theory by extrapolating his understanding of mathematics and harmonics to a planetary scale.

However, Pythagoras’ idea didn’t stand tall in his time, and it was only centuries later that it was picked up by Johannes Kepler who went on to reiterate it and further expand upon it in his own work, Harmonices Mundi. Centuries hence, our advancement in science and technology has brought us closer to listening to these songs of the universe, starting with the sound of the Black Hole, rendering a reality that was previously inconceivable and unperceived.

These extrapolated parallels drawn from our mathematical and musical understanding of the physical world have certainly helped in mapping the music of the cosmos to an extent. But when we turn our ears homewards, the story of sound takes new shapes and forms. The keynote sounds of this planet have evolved over time, leading to different soundscapes across different eras. The initial sounds on Earth, upon its formation billions of years ago, were primarily geophonic. The low-end rumble from the tectonic shifts to the crashing of water against the rocks and shores, along with world-defining cataclysmic events, dominated the soundscape till the end of the Paleozoic era 250 million years ago. The earliest forms of life in this era were underwater arthropods and cephalopods that experienced a quiet life except for soft, occasional disturbances caused by their movements and activities. The terrestrial world, on the other hand, invited life at a much slower pace and remained awfully silent for another 200 million years.

Evolution of Soundscapes

The dawn of the Mesozoic era, post the Paleozoic period, paved the way for many terrestrial life forms to thrive on land. Insects had shown early signs of sound-producing characteristics in their anatomy by the end of the Paleozoic era but biophonics began to dominate the soundscape only during the Mesozoic period. The evolved vertebrates such as amphibians and reptiles, including the dinosaurs, developed a wide range of vocal abilities, inundating the world with their calls. Mammals made their debut in this period as well. However, the fossils of these creatures didn’t leave much for us to be able to study their voices. Nevertheless, their remains did give us an interesting insight about their ears, the shape and structure of which suggested that their auditory senses were attuned to higher frequencies, helping them prey on bugs and insects. These features would have also meant that they communicated in a frequency range that was inaudible to other species, giving these mammals an advantage over their prey and predators. Adapting to the environment, their ears would have further evolved and gotten specialised in picking up ultrasonic (in the case of bats) and infrasonic (in the case of whales) frequencies. So by the time we entered the Cenozoic period, mammals were able to navigate and survive, relying solely on their aural senses, giving rise to echolocation – a whole new way of experiencing and seeing through sound.

Near the tail end of the Cenozoic period, we could ear-witness a world that had developed its sonic signature with the marriage of biophonics and geophonics, establishing many keynote sounds, signals, and soundmarks. A majestic soundscape that took aeons to take shape, was then opened up to another world of sound with the evolution of Man.

Afforestation of Noise

The earliest sonic revolution of Man began with the development of language, an ability to design and vocalise sounds that represent symbolic thought. This not only indicated a sophisticated development of the larynx and the tongue but also demonstrated a remarkable sign of evolutionary intelligence, allowing the formation of groups and civilisations that would eventually bring humans on top of the food chain and enable us to assert sonic dominance. In the next couple of millennia, this world bore witness to the life Man created at the cost of its endangerment.

Over the last few centuries, we have made immense progress in the name of development, bringing about tremendous change in not just the visual but also the aural landscape. From mining coal and oil to building railroads and airports, the rise of industrialisation and resulting global tensions engulfed the sonic spectrum like the waves of a tsunami, one after the other. The temporality of sound began to wane and we found the world sinking in this ocean of noise across frequencies. Anthrophonics took over keynote sounds of the ecosystem, overlapped essential signals, and brought down significant soundmarks, leaving many species stranded and searching for their own voice in the ensuing chaos.

Thriving in a visually driven world of progress, our primordial aural senses have taken a backseat, making us adapt to noise without protest. The essence of a world devoid of anthrophonics was briefly enunciated when Quiet rightfully reclaimed its space during the pandemic. Saving that world of sound which evolved over millions of years starting from the Big Bang not only requires us to listen attentively but also to make sonic decisions consciously in ways that are planet-driven. In this universe of controlled chaos, the symphony of our world is best heard when we learn modes of being that complement our environment instead of overpowering it.

A compilation of indicative recordings

[People who wish to contribute their recordings may submit here.]

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Padmanabhan, an industrial engineer by a degree, rode his interest as it took a radical turn towards sound and music technology out of mere curiosity. Often found trying to save his laptop from crashing, he fumbles with algorithms to create generative music and soundscapes. Under the moniker beatnyk, he has performed in spaces and events including GitHub, Goa Music Lab, Unusual London and multiple Algoraves. He is a member of Whales for Climate, a project initiated in the BeFantastic Fellowship 2021 to propel TechArt as a means to create Climate Change Awareness.

Currently found in his cave working with independent projects/artists as a sound designer.

Sound and Structure

AUTHOR

Natasha Singh

Trains, flyovers, or roads—they all stir a dream of a musical skyline. The patterns and shapes of the old buildings and minarets, when met from a moving vehicle, create an orchestra in the theatre of my mind. Walking through an urban landscape, then, is like an “alert reverie, allowing the fiction of an underlying pattern to assert itself.”i The city skyline, emerging out of various shapes and forms, “transposes [itself] onto the plane of mind” ii, making me drift to a land where I can create an incessant “stream of second attention awareness” iii. The New York skyline looks geometrical, replete with straight lines and right angles, whereas the skyline of Istanbul exhibits an abundance of symmetrical recursive patterns. These repetitive structures feel musical to me and make me wonder how different geometrical forms surrounding us would sound. Will the skyline of New York be different from Istanbul’s skyline sonically?

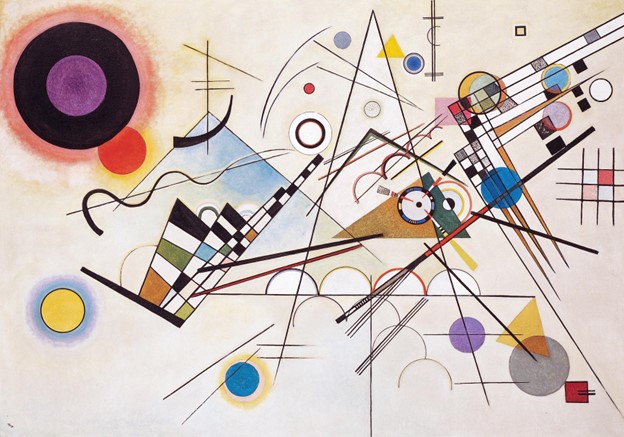

Unique structures come together to capture the essence of a city. Here, I want to investigate the ways in which spherical, dome-like shapes present a contrast to the linearity of a rectangle, sonically. How does the formation of a shape influence the sound it generates? Structural dimensions, though measurable, have an intrinsically musical character—this draws upon Kandinsky’s argument in Point and Line to Plane that elements are “sounds”: “Form itself, even if completely abstract…has its own inner sound.”iv He deduced, therefore, that all art-forms (dance, architecture, sculpture, poetry) have an elemental sound.

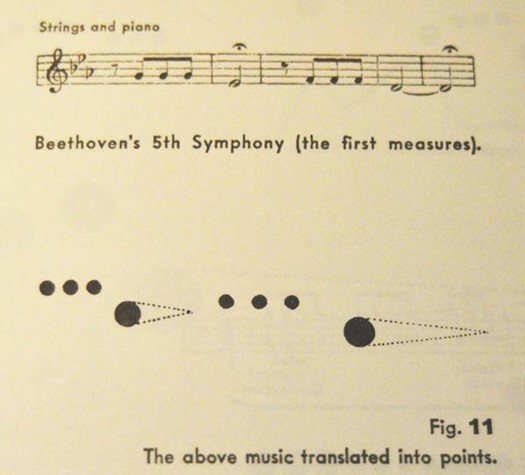

What could be a way to bring out the “inner sounds” from the shapes we see all around us? Can we bring out a common grammar for this correlation? Can the parameters of sound and line be interlinked? What would shapes sound like if we listened to them at an elemental level? Through this essay, I am considering the relationship between a point and sound, treating them as “isomorphic” v, which then enables us to map one’s properties onto the other’s, i.e., the geometry of a shape like its X and Y parameters or angular changes, onto sonic properties such as notes (pitch), velocity, duration.

At the elemental level, we must imagine a point traversing in “spaceland”vIi: the higher it goes, the higher the pitch it produces, the lower it goes, the deeper the bass sound. As Edwin Abott states in his book Flatland, space is a “thoughtland.” viii Space, in which points make a line and lines make shapes. These elements of geometry make an architecture in my mind which has a language to it, an internal sound—Kandinsky argues that “the geometric Point belongs to language and signifies Silence.” ix

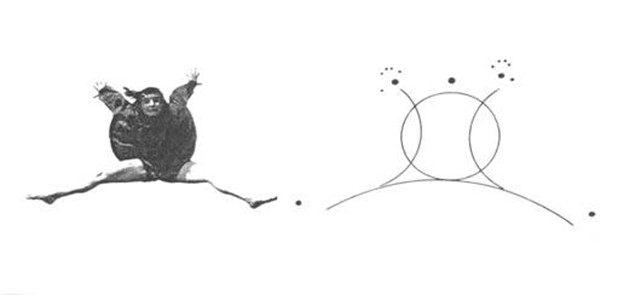

Imagine your index finger tracing a point as it moves. A stationary, silent point is given a force which makes it dynamic, and this change of state leads to the formation of a line. Kandinsky describes movement as having two elements: tension and direction. He writes, “tension is the force living within the element”x and then there is direction. A line produced with tension from a point has a sense of direction–up and down or sideways, strictly on an XY plane. The direction of a line dictates its musical nature.

Just as sound is a function of time, the length of a line “is a concept of time.”xi Just as we hear the tonal features of a sound, we can perceive the tonal features of a line– its length, the thickness with which its drawn, the direction it takes.

Let’s illustrate this:

A point moving across lines

In the above experiment, we could notice the frequency of sound being altered by the shape of the line. Another thing to notice was that the repetition of the line gave a rhythm to the sounds we heard. Regular repetitions in a line allow for the creation of a metronome-like rhythm, generating a sound with regular intervals. It is safe to say that our experiment works in accordance with Kandinsky’s statement: “Repetition heightens the inner vibration and source of elementary rhythm.”xii All forms then have a ”primitive rhythm”xiii—it is the measure of “proto-sound”xiv moving repeatedly, over the XY plane, that gives a shape a rhythm, a metre. This is the “spatialisation of musical time”xv. The “proto-sound” moves through the line repeatedly at regular intervals, producing the same sound as when it traces the repetitive nature of the line, which Lefebvre calls the “linear rhythm”xvi of a metronome.

In these experiments, I am trying to explore the rhythmic quality of a shape, by defining some rule sets for how the “proto-sound” absorbs the quality of a line or a shape.

A point moving across a triangle

A point moving across a square

A point moving across a pentagon

Here the thing to note is that geometrical points in a line act as placements for musical notes. I am playing the marimba, a musical instrument, for all the shapes now, for you to focus on the experiment. With the same notes (C4) being triggered at the vector points of the shape, what we hear is a “linear rhythm”, like a metronome.

Can we break away from the repeated tick-tock sound? What If we map the notes from C4 to F5?

Sonically mapping a triangle

Sonically mapping a square

Sonically mapping a pentagon

We can hear a difference in the notes and its progression. Mapping notes from C4 to F5 onto vector points on the Y axis, we arrive at the melodies of elementary shapes like a square or a triangle. These shapes preserve their internal melody by effectuating their geometry on an XY plane, which in turn acts like a ringtone for the shapes.

Let’s run another experiment where we change a regular shape to something irregular. Does this change bring in rhythm too?

A point moving across a square with a difference (notes are not mapped)

A point moving across a square with a difference (mapping sound on the Y axis)

A point moving across a triangle with a difference (notes are not mapped)

A point moving across a triangle with a difference (mapping of sound to y axis)

While a linear progression of a “proto-sound” represents quantified, measured time, “rhythm brings with it a differentiated time, a qualified duration.”xvii. An alteration to a repeated pattern whereby notes playing at a regular interval become altered, which is to say that if we change the length of the notes by altering the shape, the “difference” in the musicality of a shape brings with it the “definition and quality of a rhythm.”xviii

What happens when two or more shapes are played together? Does it add harmony to the sound we hear?

Two shapes playing together

Here, for example, the square acts as an “external measure” just like a metronome, or like a clock’s progression. Whereas, the altered shape of a circle brings in a change in the regular state. It can dilate or constrict: the note lengths vary and, in this case, there are longer silences than expected, thus producing an “internal measure”. That’s the idea of synchronicity between two shapes. This “double measure”, Lefebvre explains, “superimposes” its components that nevertheless “cannot be conflated.”xix

With the convergence of these ideas and experiments, I want to conclude the essay with the questions I had posed in the beginning. Can we find rhythm in the shapes and structures of the city skyline? The highs and the lows of the repeated pattern which mark the signature of the cityscape, can they also produce a distinct soundscape? Applying the same principles as discussed above, we ran the Sound and Structure experiment on two different styles of architecture, one of New York and the other of Istanbul.

New York skyline

Istanbul skyline

The city skyline has its own tonality, not to mention choice of instruments. The symmetries and repetitive forms in the Hagia Sophia of the Istanbul skyline function as an overarching context to drive the tone, whereas the New York cityscape has a distinctive rhythm of contrasting tones. The sounds I now hear when I see shapes, regular or irregular, have assumed new meanings in light of these forays. For these explorations, I would like to credit Mike CJ, a creative technologist I worked with on various fun experiments.

NOTES

i. Sinclair, Iain. Lights Out for the Territory. London: Penguin UK, 2003. Chapter 1

ii. Ibid., Chapter 2

iii. O’Rourke, Karen. Walking and Mapping, Artists as Cartographers. Cambridge: The MIT Press. 2013. 7.

iv. Kandinsky, Wassily. Point and Line to Plane (Dover Fine Art, History of Art). Dover Publications. 1980. 83.

v. Hofstadter, Douglas. Godel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. New York: Basic Books. 1999. 49.

vi. Kandinsky, Wassily. Point and Line to Plane (Dover Fine Art, History of Art). Dover Publications. 1980. 43.

vii. Abbott, Edwin A. Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions. Ingram Short Title. 2018. 124.

viii. Ibid.

ix. Kandinsky, Wassily. Point and Line to Plane (Dover Fine Art, History of Art). Dover Publications. 1980. 25. 101.

x. Ibid., 57.

xi. Ibid., 65.

xii. Ibid., 38.

xiii. Ibid., 95

xiv. Ibid., 65.

xv. Lefebvre, Henri. Rhythmanalysis, Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury. 2021. 70.

xvi. Ibid., 97.

xvii. Ibid., 86.

xviii. Ibid., 87.

xix. Ibid.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Natasha Singh likes to see patterns unfold with the interplay of Indian art and creative coding. She is an interdisciplinary artist, producing sculptures from movement-based art forms and kinetic installations from traditional drawings. As part of the research and development lab at TimeBlur, an award-winning Digital Experience studio, she explores the scope of disruptive technology to digitally conserve India’s arts and culture. Her work has been featured in The Hindu, Bangalore Mirror, Vice, The Creators Project and on Discovery Channel. Techniques like image processing, surface-filling curves, and generative art are applied in most of her current projects. Her work has been showcased at Codame San Francisco, IIT Powai Techfest, IISc Bangalore Innofest, Kala Ghoda festival, ZKM Max Mueller, Magnetic Field Festival Rajasthan, Mini-Maker Faire Bangalore. Natasha is a two-time TEDx speaker and hosts annual community workshops in making art with creative technologies.

Sonic Subversions: People’s Music at Chennai’s Margazhi Festival

AUTHOR

Krishna P Unny

The rhythmic jan jan jan of the Parai drums resound through a sabha hall, one of the many elite and conservative performance venues in the heart of Chennai. The artists dance with unmatched energy, moving from corner to corner onstage, in sync. In doing so, they claim the performance space, one that is seldom open to the marginalised. Most of them belong to the northern part of segregated Chennai, home to several Dalit performing communities, including those of Parai and Gaana artists [i]. Through their forceful drumming, they mark their presence sonically in the rest of the city—the posh, upper-caste neighbourhoods in central and south Chennai where it’s often the tha dhi thom nam-s of the classical Mridangam that dominate the rhythmic soundscape.

For almost a century, between December and January every year, the privately owned sabhas in this part of Chennai have hosted over 3000 music and dance performances as a part of the city’s ‘Music Season’. Falling in the Tamil month of Margazhi, this annual festival celebrating Chennai’s rich musical heritage has even given the city a place in UNESCO’s global Creative Cities Network. Yet, these festival spaces remain exclusionary. Organised by and for upper-caste, upper-class (often NRI) crowds, Carnatic music and Bharatanatyam concerts make for most of the Margazhi events [ii]. Subaltern performance practices are relegated to the margins, much like the communities of their practitioners.

In 2020 and 2021, the Margazhiyil Makkal Isai—People’s Music at the Margazhi—was organised by the Neelam Cultural Centre, an Ambedkarite arts organisation founded by eminent filmmaker and anti-caste activist Pa. Ranjith. The festival hosted previously excluded artforms and artists in Chennai’s prominent sabhas. The Parai performance marked the inauguration of the Margazhiyil Makkal Isai (henceforth MMI). This was followed by a presentation of Tamil ‘folk’ musical forms such as Oppari, Gaana, Nattupura padal and a ‘tribal music show’, among others. Diverse themes sprang from the songs performed—while some celebrated nature, language, love, unity, and resistance, others delved deep into loss, grief, struggle, and the mundanities of life. In the predominantly Brahminical venues which associate themselves with the ‘classical’ and therefore spiritual, these everyday songs and sounds of the people take on a new meaning. They give voice to Dalit agency [iii]. The music festival then becomes a site of sonic subversion. In this essay, I go a step further and argue that the disruptive element here is not simply the assertion of identity through sound, but the fact that the MMI used the very ability of sound to coalesce a community to create a larger Dalit solidarity.

Sonic Solidarities

In his 1972 novel Mumbo Jumbo, a satirical work of fiction set in 1920s America, Ishmael Reed talks about an epidemic caused by the “Jes Grew virus”. Unlike other viruses, Jes Grew did not cause physical illness. Instead, the infectious virus forced its hosts to listen to music, sing, and dance, leaving them more energised and ecstatic than before. For Reed, the virus symbolised Jazz and other Afro-American musical forms. It also represented the African diasporic cultural ethos of freedom and self-expression [iv]. The orthodox white American characters in the story found the virus ‘threatening’ lest it wreak havoc and start a pandemic. Spreading like wildfire, it brought many under its powerful influence.

Commenting on Jes Grew, Alex de Jung and Marc Schuilenberg contend that popular music creates an environment that makes it difficult for its listeners to remain neutral or distant. It pulls them in. The “sound virus”, as they argue, infects individuals, moves them, and brings them together in “sound communities” [v]. Sound communities have been defined as “clusters of social relations which emerge through a collective commitment to specific categories of sounds”. They come together “to interrupt or otherwise subvert dominant sound patterns” [vi]. Jes Grew too helped create a community of listeners of African-American music in a society dominated by white Americans.

In 2020 and 2021, the MMI was organised in Chennai—with necessary restrictions—while the city was tackling a global pandemic caused by the coronavirus. Unlike Jes Grew, the virus was real. Though highly uncharacteristic of Chennai in December, the city was silent. Most sabhas switched to virtual festivals and there was a significant lull in the sabha economy—that is perhaps what allowed the idea of the MMI to take shape. Despite the hurdles, the festival hosted over 500 artists from across Tamil Nadu and the performances were attended by a large and diverse audience. While it can be unnerving to read Reed’s virus alongside its real and disastrous counterpart, the idea of ‘sound communities’ is important for us to understand the implications of the MMI. Like Jes Grew, the festival too attempted to forge its own sound community. And this was achieved, I argue, by articulating or suturing the many Dalit sonicscapes within and outside the city [vii]

In Chennai and elsewhere, if you lend your ears to the soundscape, you notice that each nook has its own musical sounds and rhythms that it cherishes. For instance, different parts of Tamil Nadu have their own unique Parai taalams or rhythmic patterns [viii]. These regional differences create distinct soundscapes. It also creates a sense of regional identity among its artists and listeners. We see this in the case of Gaana and its relationship with north Chennai. While many mainstream Tamil movies often represent the area as a violent urban ghetto [ix], the lyrics of many Gaana songs attempt to undo this notion. They speak of the cultural moorings of the singers to these neighbourhoods and redefine them as spaces marked by love, kinship and a common struggle against oppressive systems—an example being Casteless Collective’s ‘Vada Chennai.’ This is much like Hip Hop, which as Johansson and Bell note, ‘constructs places […] such as the ghetto […] where these spaces, as symbols, provide the African American community with an identity […] now central to the form’s authenticity’ [x]. These individual, regional, and ‘authentic’ Dalit sonicscapes came together in the festival space of the MMI.

The Infection

Many young Tamil Rap artists, senior Gaana artists in Chennai, and performers from indigenous communities such as the Irulars and Kurumbars from elsewhere in the state, shared the same stage at the MMI. They performed together. The listeners of the music, coming from diverse socio-cultural backgrounds, were also active participants in the performance. They sang, danced, and cheered for and with the performers. The artists and audience exchanged intermittent ‘Jai Bhims’ and responded to common symbols and sounds of anti-caste resistance and solidarity—the Parai, songs on Buddha and Ambedkar, speeches on shared Tamil roots. Through these, they allowed themselves to move and be moved. In other words, Reed’s sound virus was at play. When the Parai drummers danced, beating the drums and asserting their voice, they too were acting as carriers, transmitting sounds and sharing sound experiences, and through these sonic interactions, forging a community.

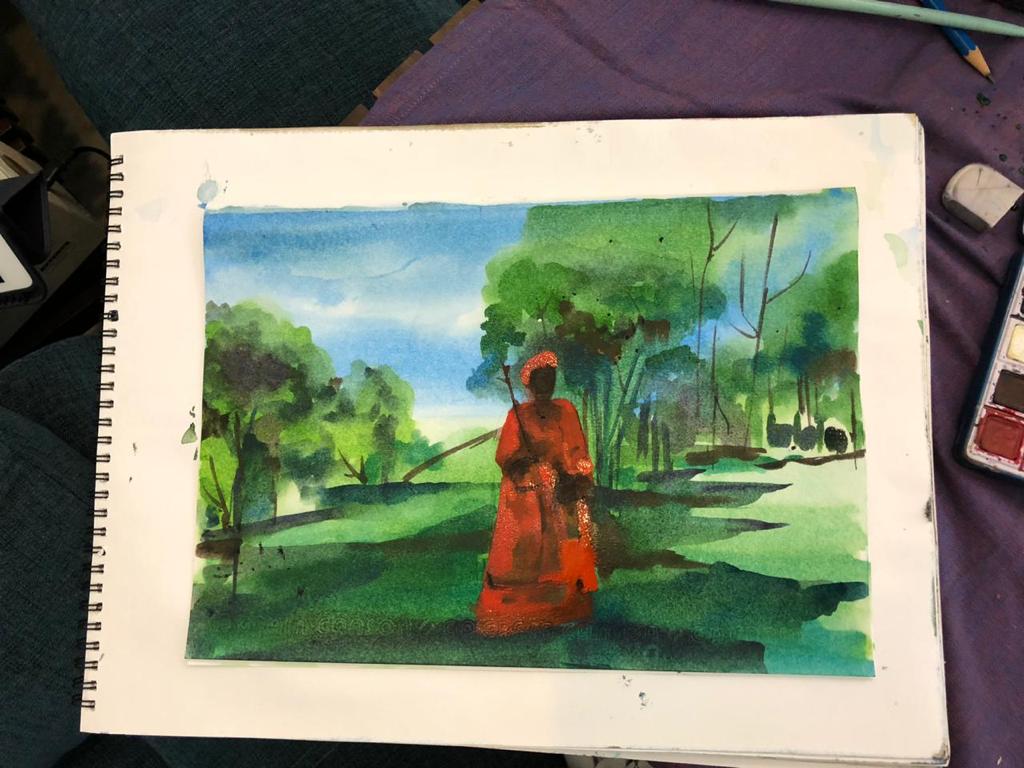

MMI 2021, Krishna Gana Sabha, Chennai, Day 5 (Author’s Collection)

NOTES

[i] The Parai is an indigenous drum played by the Paraiyar community at weddings, temples, and funerals. Oppari refers to songs of lament or ritualised mourning. Gaana has its roots in north Chennai where it was performed as funerary music. Due to the associations of these forms with death, the forms and the communities of artists associated with them have been stigmatised. In the work cited below, Diwakar writes about the close links between Gaana and the northern, neglected part of the city.

Diwakar, Pranathi. “The Other City: Gaana Music Challenges the Singular, Homogenising Narratives of Chennai City.” Economic and Political Weekly. vol lV no. 4, 2020.

[ii] T.M. Krishna, Davesh Soneji, Nrithya Pillai among others have written about the caste and class exclusivity in Chennai’s classical music and dance scene. Charulata Mani’s recent work also delves into this. See,Mani, Charulata. “Chennai at the Cusp of Cultural Change”. Ballico, Christina, and Allan Watson, editors. Music Cities: Evaluating a Global Cultural Policy Concept. Springer, 2020.

[iii] Weidman, Amanda. “Gender and the Politics of Voice: Colonial Modernity and Classical Music in South India.” Cultural Anthropology, vol. 18, no. 2, 2003

Here, Weidman writes about the upper-caste women as Carnatic music performers in the early 20th century south India and highlights the link between the singing voice and agency.

[iv] Hawkins, Alfonso W. “Madam Zajj and Jes Grew: Ishmael Reed’s Codified Jazz Texts.” Obsidian III, vol. 5, no. 1, 2004.

[v] De Jong. A, Marc Schuilenberg. Mediapolis: Popular Culture and the City, 2006

[vi] Straw, Will. “Rhythmanalysis and Circulation” The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music, Space and Place. Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

[vii] I borrow the term from Davesh Soneji but use it loosely to refer to the regional soundscapes of Dalit neighbourhoods, many of which perform/meet at the festival space.

[viii] In an interview for The News Minute, Parai artist Manimaran discusses the reasons for the disappearance of different thalams of Parai practised in different regions. See,

Singaravel, Bharathi. “The Parai: Then and Now, the Instrument Plays a Key Role in Anti-Caste Struggle”, The News Minute, Aug, 2021.

https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/parai-then-and-now-instrument-plays-key-role-anti-caste-struggle-154197

[ix] Damodaran K., Gorringe H. “Contested Narratives: Filmic Representation of North Chennai in Contemporary Tamil Cinema”, Tamil Cinema in the Twenty-First Century: Caste, Gender, and Technology. Routledge, 2021.

[x] Johansson and Bell, quoted in,

Stahl, Geoff. “Music, Place, Space, Non-Place” The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music, Space and Place. Bloomsbury Academic, 2022.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Krishna P Unny is a student of dance and history interested in performance studies, cultural histories, and performing arts practices of South Asia. She is a Young India Fellow from Ashoka University where she also recently completed her Master’s in Liberal Studies. For her graduate thesis, she worked on the Margazhi festival in Chennai using transdisciplinary frameworks of rhythmanalysis, caste, urban space, and performance. Krishna is the curator of @madrastically_yours — a pet project where she documents Chennai’s history and heritage. She currently works as a Research Associate at the MAP Academy, Bengaluru.

Building Bodies of Song: Community Singing and Vernacular Song Archives in a Pandemic

AUTHOR

Shruthi Veena Vishwanath

साखी

Sakhi

8:55 AM

(Everyday from 31 Mar to 6 June, 2020)

Arshinagar, Gourbazar, West Bengal

With a bit of acrobatics, I can manage phone, tripod, ektara, bama, ghungroos, all at once. I take them to the Machan, an open bamboo structure in the centre of Arshinagar. Two minutes later, I am sitting on the platform, cross-legged, tripod on the red earth, squinting into my phone to check if the internet gods are on my side. When the home screen clock flashes 9:00, I go to ‘Start Meeting’. Deep breath. Smile. It’s the only concert that’s going to happen for a while. “Good Morning!”

ಗಮಕ

Gamaka

I never believed in online music. My YouTube presence is fairly sparse, my website hasn’t been updated in 30 months. I used to laugh at fellow musicians who said they taught on Skype. But when the pandemic hit, I wondered what I could do in a world full of suffering, and I realised I needed to offer what I knew best: song.

At some point, caught between teenage angst and math tuitions, we begin to forget. The image of the two mountains with the sun and the river disappears from our drawing books, we forget to do a little jig when we are happy, and music becomes the FM channel while stuck in morning traffic. The groove and voice that make us who we are get forgotten with conditioning, pushed deep down into our bodies.

தானம்

Taanam

This has always felt strange to me: I know 6 languages, and yet English is my language of thought and expression. In the other 5, I get called out one way or another. I cannot read or write in my mother tongue, although I speak it. One language betrays my caste markers, I’ve been told. In another, I cannot speak more than 2 sentences without stumbling.

And yet these languages are all me, in delightfully contradictory ways. When I sing these languages, I feel whole. The pronunciation is easy and the changing musical idiom becomes a portal to different parts of me, parts that have been sidelined in my formal education. The more languages I sing in (about 15 more languages currently, from not only South Asia but also Eurasia), the more my body and breath become my own. English then becomes a mere medium for expressing verbally when I have to, and for singing a few songs that I love.

“Till I came here, I always thought that this (regional language) music was very removed from my world. I thought I would never be able to sing like this, sound like this, even though it spoke to me and resonated with me. The Machan has made it really accessible. Of course your facilitation, but beyond that, everyone in the space has helped me out—with pronunciation, with mistakes. I try and feel it and honour the legacy of where this music comes from.”

(Kavya Srinivasan, part of the Music in the Machan community)

আখর

Akhor

A month into this song experiment, I realised that this group of people had the resources to help alleviate the terrible on-ground situation in rural Bengal, where I was locked down for the first three months of the pandemic. A simple call on the group raised enough money to get basic rations for 200 families for 2 months. Song suddenly had power.

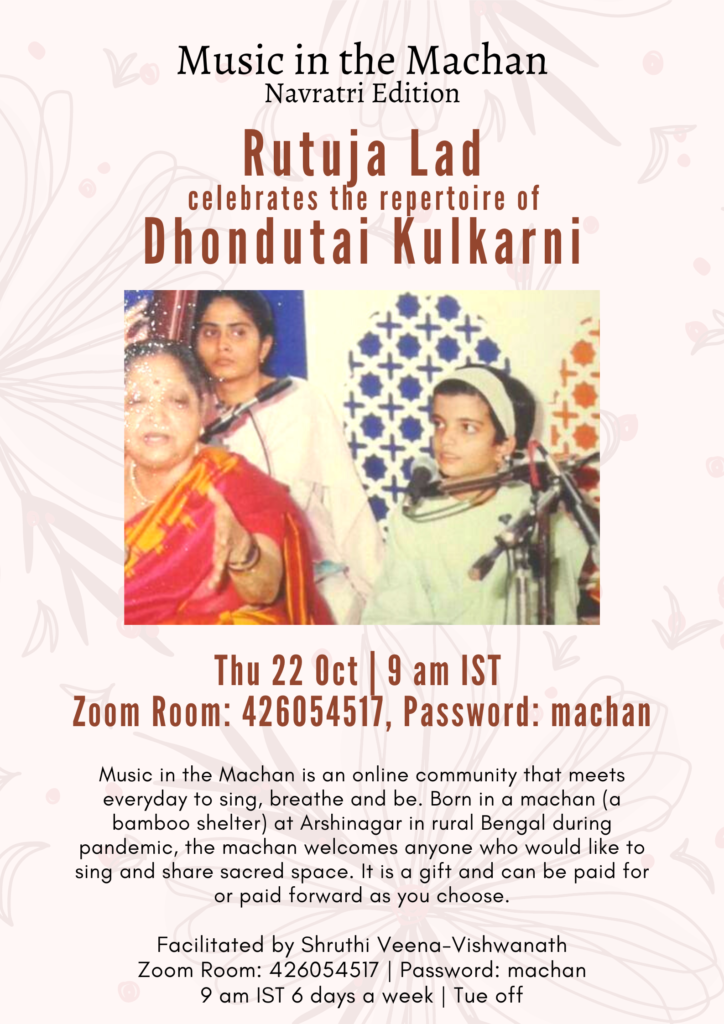

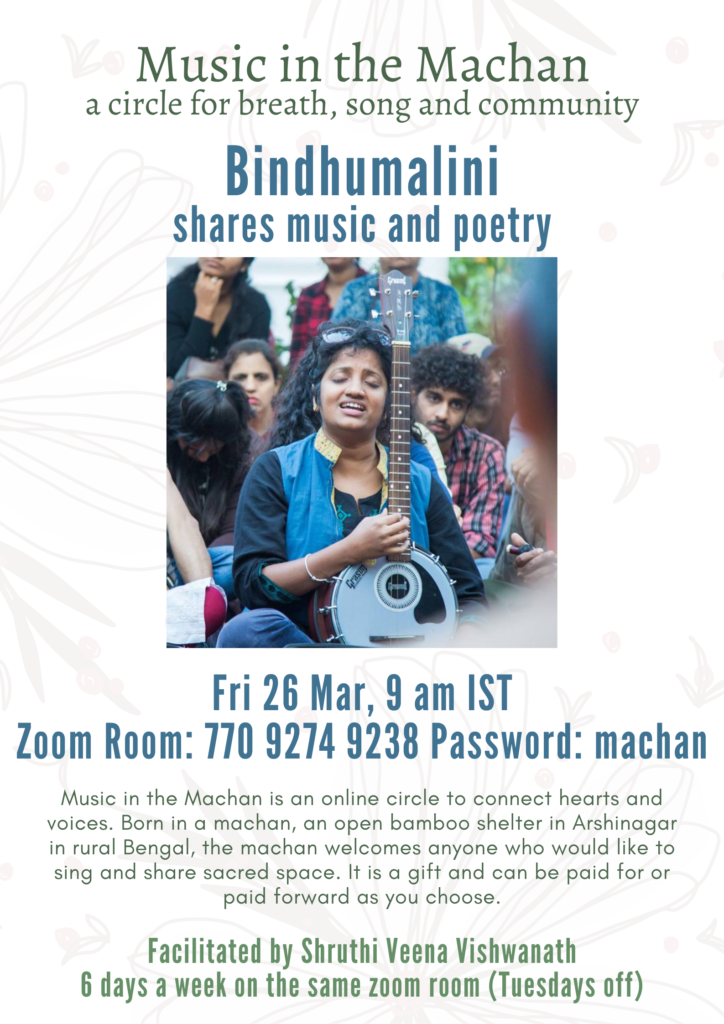

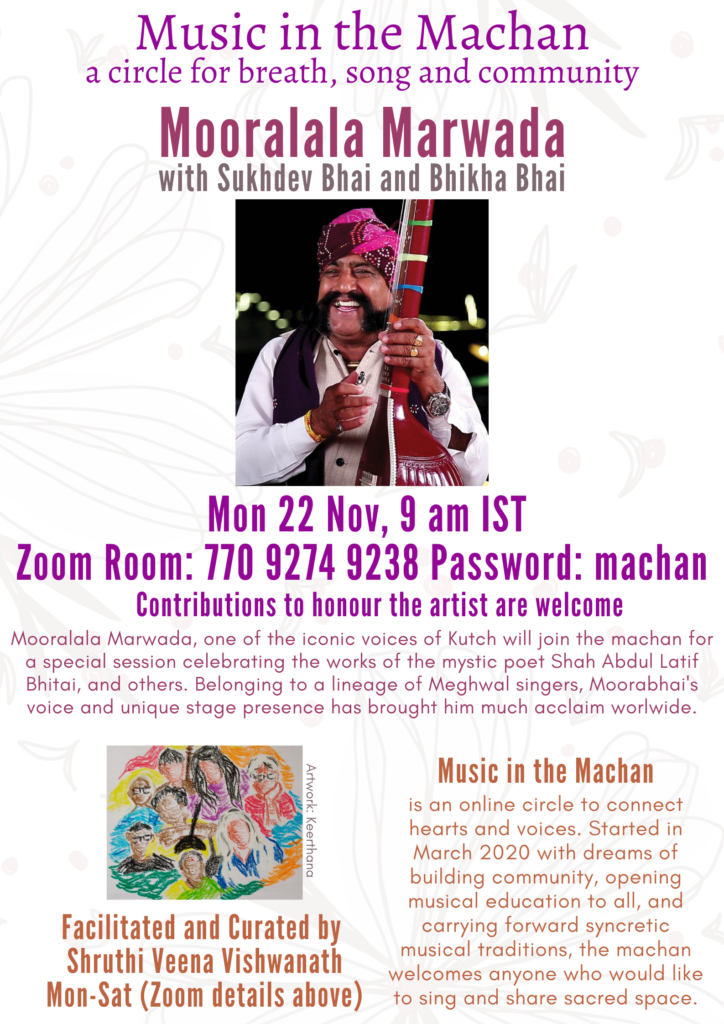

I also wanted to bring guest artists to perform and teach, since all concerts had stopped. I invited my host Uttam Das, a musician with deep knowledge of North Bengal folk, Baul, and Kirtan to teach a song. It was a ‘goshto gaan’ (grazing song) from Gourbazar, the village where we were based. Usually, people teach popular songs, but Uttamda chose to teach something close to his heart. That set the tone.

We had guest musicians once a month. Radhika Sood Nayak with Punjabi Sufi, Prahlad Singh Tipaniya with Kabir in the Malwi style, Vedanth Bharadwaj with songs from MK Gandhi’s Ashram Bhajanavali, Purabi Bhattacharya with Assamese and North Bengal folk songs, among many others. Musicians from West Bengal, the land that most lovingly nurtured this music offering in its early days, tuned in from Gourbazar and surrounding areas. Nemai Das Baul, Netai Chandra Das, Shyamsundar Das Baul came to perform and teach Baul songs. Anathbandhu Ghosh shared Geet Govindam and Vaishnava songs. Mir Basu Barkat Khan, a Mir musician from the village of Pugal, Rajasthan, did a 4-part taught series on Sufi songs in Saraiki and Punjabi.

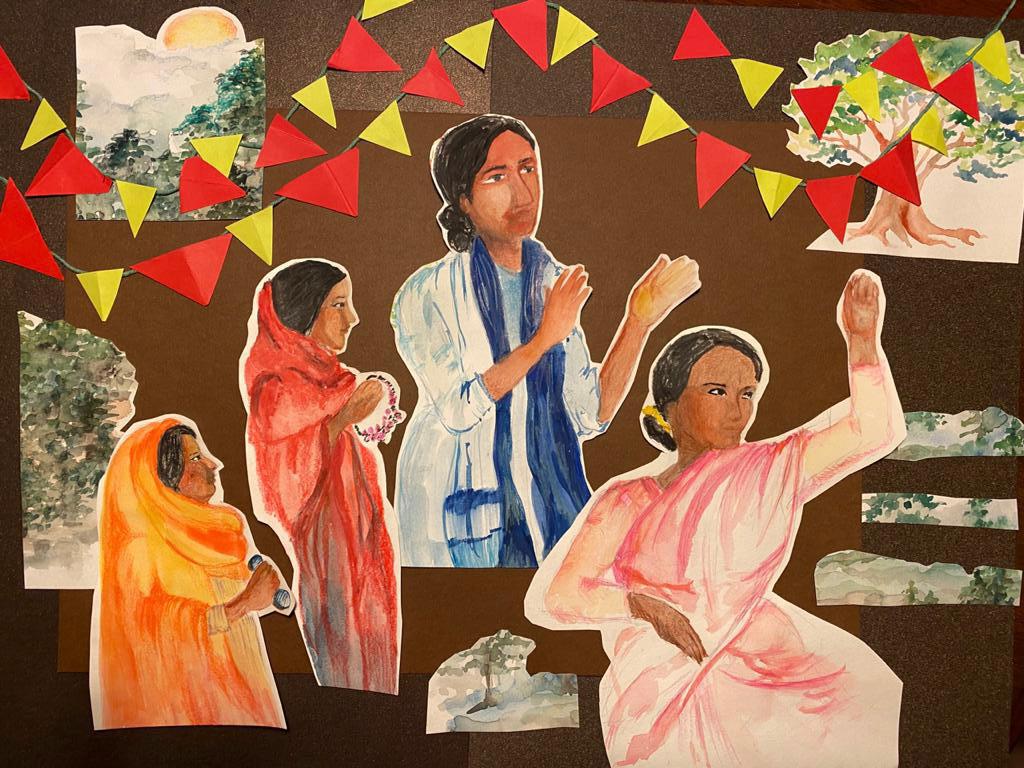

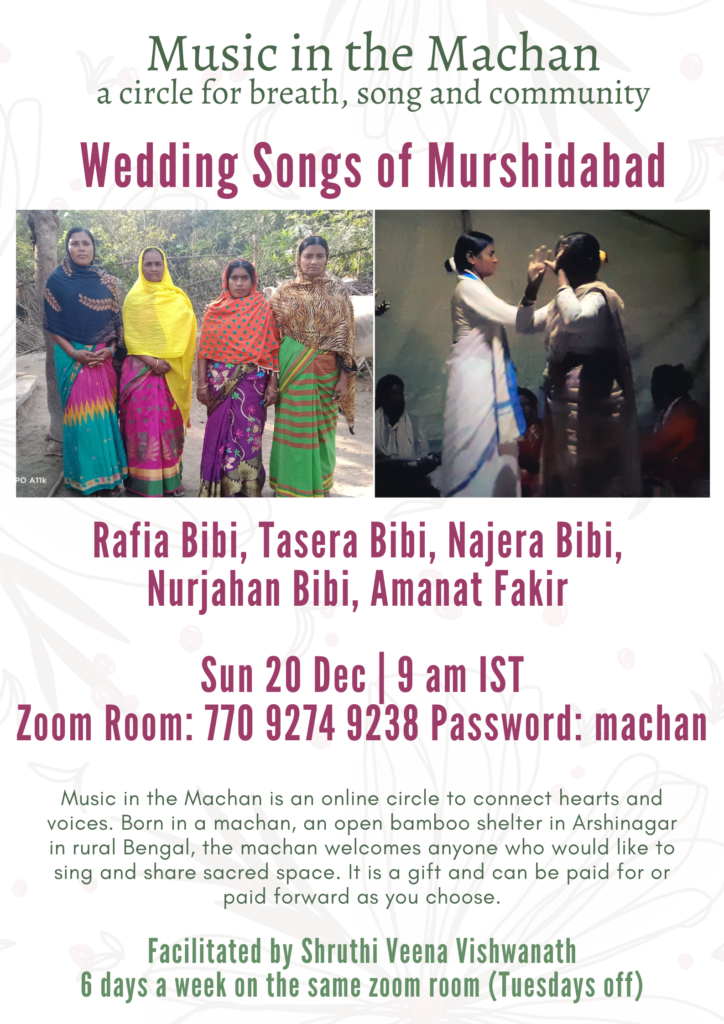

What was critically important for me was that the guest artists also shared their authentic artistic selves at Music in the Machan, and these guests were as diverse as my networks and budget could permit. Rina Das Baul, a rare woman performer in the Baul world, sang one morning and later came to teach. Rafia Biwi, another exceptional woman artist in the Fakiri tradition, came with Tajera Biwi, Nurjahan Biwi, and Nasera Biwi, travelling 9 hours from Murshidabad to Gourbazar, to perform wedding songs. Rafiadi is well known in the region, but the other women had their names on a poster for the first time. Ramakka Jogathi, a wonderful chowdaki player and singer from a North Karnataka community of transwomen called Jogathis, shared her music with us. Shilpa Mudbi Kothakota, herself a brilliant performer and researcher, joined in to support Ramakka with translations.

“Mostly, I am just too shy to sing unless called upon. And yet, the songs stay. So many whose meanings I don’t know, so many that I never imagined would speak to me, and yet the songs stay…”

(Isha Nigam, part of the Music in the Machan community)

जोड

Jod

Singing for an hour a day initially felt like a concert, then later like a public riyaaz session. But soon, I wanted to hear voices other than my own and that of other professional artists. This desire sprang from my belief that we all have a voice and a song waiting to emerge from underneath layers of conditioning.

With time, the community started to sing. Somebody shared a song dear to them, others followed. Then we did ‘rounds’- one song in a session would travel around in a circle (or Zoom rectangle) and everyone would sing a verse or a fragment of the song. Jayaram, a member of the Music in the Machan community, was the one to fearlessly jump in and sing right after me. Others were soon motivated by him, and the fear and hesitation slowly faded. To this day, it is (unspoken) tradition for him to kickstart a round.

My regular co-musicians Shruteendra Katagade and Yuji Nakagawa, accomplished artists on the tabla and sarangi respectively, got inspired and came to share songs. Yuji shared a deeply moving tribute to his guru Dhruba Ghosh, on his barsi. Shruteendra has come several times since to share the compositions of his guru’s father, Dinkar Kaikini. He has even started singing a song or two occasionally in our concerts together, leaving the tabla for a few minutes to use his voice.

“I’ve been assimilating these songs all my life. But suddenly the songs with their layered meanings burst out. Perhaps I needed a platform to share it with people, and the Machan encourages you to speak your true self. I now feel like a bowler who can also bat and wicketkeep! The music in me has deepened…”

(Shruteendra Katagade, tabla player, teacher and vocalist, on Music in the Machan)

خانة

Khana

In the early days of Music in the Machan, around the same time that we came up with the name, folks who sang regularly started gently nudging me to record the sessions. As someone who has done hours’ worth of recording at concerts right from childhood, with no patience whatsoever to catalogue and label, I was reluctant. But then someone couldn’t come for the live sessions because they were caring for an aged parent, and I agreed. Sarada and Anisha, two people who have been there since the first day, started recording and uploading sessions onto YouTube as unlisted entries. They also started a shared document to compile lyrics. Several members volunteered to type or translate songs. Keerthana, Adithya, Kaustubh, Aanchal, Veena and others started drawing in response to the Machan sessions.

I had been holding Music in the Machan 6 days a week for 2 years and 3 months, without a significant break. When I got an invitation to tour abroad for 6 weeks, I wondered what would happen to the space. Would it fizzle out? We had had some members of the Machan community lead the occasional session, doing art and song and yoga. We had had some group sessions on the odd day that I didn’t have internet. But 6 weeks?

People took the responsibility of leading the sessions in rotation. Someone would volunteer every day. There was not a single day that the session didn’t happen. I had started and led the Machan, but somewhere along the way, Music in the Machan had truly become a community.

చరణ

Charana

Within any community, disagreements may happen. Music in the Machan is no exception. We are, after all, a microcosm of the fragile world that we live in. But we have tried to work through these conflicts and have had Machan sessions specifically to ensure dialogue. There are times when a song or story shared by someone has made me uncomfortable, and I’m sure people have been made uncomfortable by some of my choices of song or word. When I wanted to share a bunch of guidelines that reflected my personal politics, I was asked by a friend: “Do you want to be in an echo chamber or to create a source of infinite light? Do you want the Machan to only be a space for people like you?”

I didn’t share the guidelines.

The songs we have taught and shared—a majority of them from oral Bhakti, Sufi, Baul, Nirguni, Vachana traditions—have been on the frontlines of our wrestle with questions of caste, gender, and religion for centuries now. That isn’t entirely by accident. While these themes are the central aspect of my personal repertoire, any song circle that has gone on for over 800 days (almost consecutively) needs songs with nuance to thrive. These songs have historically risen from the people. By the people, for the people, always resisting power structures. For the Machan to reach people and truly become a place for embodied songs, we who constitute it need to keep asking difficult questions, within and beyond.

Encore

Music in the Machan meets on Zoom from Monday to Saturday at 9:00 AM IST. The archive of songs, recordings, and lyrics is open to anyone who wishes to access it. The Machan is a gift that can be paid for or forward into the world. Anyone is welcome! Write to [email protected] to know more.

Music in the Machan will have its first offline retreat in Goa in September 2022. It will have guest artists and community singing as well as learning.

Some Guest Musicians

ABOUT THE AUTHOR