Up and down the whole hungry longitude

AUTHOR

Avani Tandon Vieira

On the corner of Rampart Row, across from Rhythm House in Bombay’s Kala Ghoda district, poet and artist Arun Kolatkar sits at a table at the Wayside Inn. It is a Thursday afternoon in the 1960s, and like every other Thursday, Kolatkar is gradually joined by friends and acquaintances – painters, poets, editors – who drop in for a conversation, to read a new poem or to hear one read, or simply for a cup of tea.

The Wayside Inn has stood at this spot for nearly five decades. Taken over from an Englishwoman by the Parsi Patel family in 1933, the restaurant serves a mix of foods as eclectic as its history – fish and chips served alongside spaghetti Bolognese and mutton Dhansak. Its mismatched tables and triangular, high-ceilinged interiors welcome intellectuals, poets, and statesmen, casual conversations at one table, drafts of the constitution at another[1]. On this Thursday, its corner table hosts, among others, one of the foremost Indian poets of the twentieth century.

From his vantage point at the Inn, sometimes accompanied, sometimes not, Kolatkar watches the city go by. A watermelon seller pushes his cart through the streets as an idli vendor sets up shop. A fisherwoman on her way to work stops for breakfast at a tea stall. The rat poison man puts his wares aside, settles on the pavement, and has his lunch. The city rises and rests, opens and closes, eats and eats and eats.

For Kolatkar and his circle of contemporaries, the Wayside Inn is part of a constellation of sites – cafés and restaurants and bookshops – that make up the city of the writer and the artist. Around the corner, at Café Samovar in the Jehangir Art Gallery, painters S.H. Raza, M.F. Husain, and K.H. Ara chat over Kheema Paratha and Boti Rolls. Among the checkered tablecloths and mirrored walls of dozens of Irani cafés dotting the city, writers and students alike consume bun maska and make idle conversation. The city’s eateries offer shelter, cheap nourishment, a moment of respite.

In Bombay, today as in the 20th century, all existence is precarious. To make a place for oneself is an exercise in tenacity, to make a life an exercise in resourcefulness. What is true of everyday life is true, also, of the act of artistic making. In the early decades of the nation, a self-sustaining culture of avant-garde art and writing began to emerge in Bombay. In the absence of institutional support or public recognition, young painters and poets collectivised to create modes of expression suited to their experience. Their challenge in this endeavour, alongside youth and a lack of means, was that of space.

Reflecting on the contemporary state of the American avant-garde, critic Lucy Sante argues that “an avant-garde needs a scene, and the cities are too expensive for scenes now. An avant-garde needs an excess of time, and that’s in short supply nearly everywhere”[2]. These dual concerns – of space and time – are universal. Several decades and thousands of miles away, they stood in the way of young artistic voices in 20th century Bombay. To address them, these artists turned to informal frameworks of literary-artistic assembly, frameworks that often had at their heart a food site. For filmmaker Arun Khopkar, the emergence of these spaces lies in the spontaneity of Bombay’s growth, and the absence, subsequently, of an effective plan for its development. The city’s chaotic “anti-planning”, Khopkar argues, unintentionally created “perfect incubators” for innovation in the arts; cafés, restaurants, and bookstores becoming “nerve centres” of the city’s cultural life[3]. Chief among these were the city’s many Irani cafés, which Khopkar describes as the “cheapest of subaltern clubs”.

Bombay’s Irani cafés trace their history to patterns of migration between the then neighbouring States of India and Iran. Iranian migrants travelled to India for trade and business, settling in Surat and Ahmedabad before eventually migrating to the financial capital of Mumbai. This period of resettlement in the 19th century coincided with an industrial boom, bringing thousands of workers, all in need of cheap and accessible meals, to the city[4]. Among these crosscurrents, Irani cafés provided nourishment for people of all faiths and backgrounds, serving as “a kind of poor-man’s roadside parlour where secrets and sorrows could be shared along with a leisurely cup of tea”[5]. The food served at these cafés was born of a mix of traditions, blending Iranian flavours with dishes from the Goan, Gujarati, and Mughal traditions. Gujarati staples were tempered with meat, Iranian flatbread replaced with the locally inspired brun. Blending culinary traditions and communities, Irani cafés became “Bombay’s first public eating places”[6], permitting space and time to citizens and poets alike.

In much the same way, Café Samovar was opened in 1964 in the image of Paris’ Left Bank cafés, “to fill a lacunae in the city”[7]. Where, its founder Usha Khanna found herself asking: “Would artists meet their patrons? Where would poets write without being disturbed? Where would students go on a date they could afford?”[8] The answer came in the form of the corridor-like eatery at the Jehangir Art Gallery. Samovar provided “home-style food for out-of-towners, students and other indigent Bombayites”[9], its menu an eclectic mix of dishes – Kheema Paratha, Dahi Vada, Pakodas, and Mint Tea – that were modestly priced and rarely changed. Over its nearly five-decade run, the restaurant was visited by actors and writers, lawyers and students, big names like Dilip Kumar and Husain rubbing shoulders with generations of Bombayites. In a corner of the city, sandwiched between a gallery space and a garden, the people of the city found a space for romance, small talk, art and many things in between.

Such acts of spatial remaking remain commonplace in Bombay. In a city lacking stable infrastructure, public spaces, or a robust system of libraries and art centres[10] (an accessible public commons, in other words) everyday spaces become rich, multivalent sites of community life. As the urban domain grows ever narrower, space is at once prized commodity and pliable, continually reclaimed resource. In the hands of the city’s populace, pavements become sites of commerce, traffic islands breakfast spots, and roundabouts places of leisure. Beyond the limits of the formal map is a liminal Bombay of the everyday: a set of geographic markers that exist in public memory but outside geographic fact. These landmarks of the ordinary citizen, multipurpose and movable, remake the city in the image of those who occupy it, resisting the tendency of the official map to, in the words of de Certeau, “[cause] a way of being in the world to be forgotten”[11].

Within the worlds of 20th century artmaking, the coordinates of the avant-garde performed a similar function, eking out space for practitioners who would otherwise be invisible. For the artists and writers of the 1960s, food served as link, tool, and subject. The spaces in which it was consumed were at once social and professional, allowing for nourishment and comradery alongside the development of new forms and idioms. In places like the Wayside Inn and Café Samovar, the poetic and the everyday bled into each other. These sites provided a place for food to be consumed and relished, for work to be exchanged, and for the city to be observed and documented. What emerged was a creative practice enmeshed in the texture of the city, an approach to creation deeply attuned not just to what was being said but also to where it was being said from.

Sitting at his regular table at the Wayside Inn, Kolatkar would pen dozens of poems about the lives and rhythms he was witnessing. The watermelon seller, rat poison man, and fisherwoman became his protagonists, their daily routines the subject of his work[12]. In their own ways and mediums, his contemporaries displayed a similar loving attention to the everyday, creating little magazines, paintings, and poetry that recognised the city – crowded, filthy, humble, alive – as worthy of art. In encountering portraits of the urban across aesthetic and temporal distance, it is sometimes possible to take a sanitised view of art-making, separating it from the material constraints that so often circumscribe its creation. The cultures of independent art-making in the 1960s, deeply reliant on the resources available to them, deny such distance. Instead, they deliver us to the intersection of creative practice and everyday life, revealing how the city’s cultures of eating, movement, and leisure are foundational to the art that is produced within it.

The essential question of nourishment – both metaphorical and literal – is a pathway to a fuller understanding of artistic production. In viewing the work in light of that which sustains it – space, time, resources – we may reveal the profound material requirements of creative practice. Food, as one among these, functions as a barometer of cultural life. Food is communal, public, collectively negotiated. It acts as a nucleus of social life and a marker of cultural identity. In asking who is permitted to eat, where they can eat, and what they are eating, we are asking, also, who the city belongs to.

In a sequence from his poem “Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda”, Kolatkar records a set of meals – “khima pao at Olympia/ dal gosht at Baghdadi/ puri bhaji at Kailash Parbat…”- that is being eaten “up and down/ the whole hungry longitude”[13]. Many of the spaces in the poem are now gone, built over in the ceaseless forward march of the city. But Kolatkar’s work is more than a document of a place and time. It is a reminder of a way of being in the city, one that persists even after its coordinates have been erased. Today and tomorrow and the day after that, Bombay’s residents will find space to eat and drink and rest. They will stop on pavements and at run-down cafés for a quick meal or a slow chat. Perhaps someone will witness this and think to write about it. Perhaps not. It will happen anyway.

Works cited

Bhatia, Sidharth. “Mumbai’s iconic Café Samovar was an island of calm in a frenzied city”. Scroll.in, 19 March 2015. http://scroll.in/article/714775/mumbais-iconic-cafe-samovar-was-an-island-of-calm-in-a-frenzied-city.

Certeau, Michel de. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Guha, Kunal and Gehi, Reema, ‘‘Goodbye, Sam’s’. Mumbai Mirror.” Mumbai Mirror, 19 March 2015. Accessed 12 September 2023. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/cover-story/goodbye-sams/articleshow/46615415.cms.

Khopkar, Arun. ‘Footloose and Fancy-Free in Bombay: A Partial View of the 1960s and 1970s’. Journal of Postcolonial Writing 53, no. 1–2 (4 March 2017): 12–24.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17449855.2017.1289612.

Kolaṭkar, Aruṇ, and Mehrotra, Arvind Krishna. Arun Kolatkar: Collected Poems in English. Tarset: Bloodaxe, 2010.

Kolaṭakar, Arun. Kala Ghoda Poems. 1st ed. Mumbai: Pras Prakashan, 2004.

Marfatia, Meher. “History and Tea at Table No. 4”. Mid-Day, 25 January 2015. https://www.mid-day.com/news/india-news/article/history-and-tea-at-table-no.-4-15940170.

Sante, Lucy. “That Moment Barely Survived”, The Drift, 9 July 2023. https://www.thedriftmag.com/that-moment-barely-survived/.

Patel, Mira. “Bun Maska and berry pulao: The history of Mumbai’s Irani cafés”. The Indian Express,12 November 2022. https://indianexpress.com/article/research/a-feast-of-berry-pulao-how-the-irani-cafes-of-bombay-served-as-socio-economic-levelers-8263822/.

Tickell, Alex. ‘Writing the City and Indian English Fiction: Planning, Violence, and Aesthetics’. In Planned Violence: Post/Colonial Urban Infrastructure, Literature and Culture, edited by Elleke Boehmer and Dominic Davies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, imprint of Springer Nature, 2018.

Notes

[1] B.R. Ambedkar is remembered to have drafted “his monumental work between pots of ordered tea” at the Wayside Inn in 1948. See Meher Marfatia, “History and tea at table no. 4”, Mid-Day. 25 January, 2015. https://www.mid-day.com/news/india-news/article/history-and-tea-at-table-no.-4-15940170

[2] Lucy Sante, “That Moment Barely Survived”, The Drift, Issue 10

[3] Arun Khopkar, “Footloose and Fancy-Free in Bombay: A Partial View of the 1960s and 1970s”, Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 53.1–2 (2017), pp 12–24.

[4] See Mira Patel, “Bun muska and berry pulao: The history of Mumbai’s Irani cafés”, The Indian Express. 13 November, 2022. https://indianexpress.com/article/research/a-feast-of-berry-pulao-how-the-irani-cafes-of-bombay-served-as-socio-economic-levelers-8263822/#:~:text=In%201854%2C%20a%20party%20 named,the%2019th%20century%20onwards.

[5] M G Moinuddin quoted in Mira Patel, “Bun muska and berry pulao: The history of Mumbai’s Irani cafés”.

[6] Mira Patel, “Bun muska and berry pulao: The history of Mumbai’s Irani cafés”.

[7] Khanna quoted in Kunal Guha and Reema Gehi, ‘Goodbye Sam’s”, Mumbai Mirror. 19 March, 2015. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/cover-story/Goodbye-Sams/articleshow/46615415.cms

[8] Ibid.

[9] Sidharth Bhatia, “Mumbai’s iconic Café Samovar was an island of calm in a frenzied city”, Scroll.in. 19 March, 2015. https://scroll.in/article/714775/mumbais-iconic-cafe-samovar-was-an-island-of-calm-in-a-frenzied-city

[10] Alex Tickell argues that “the planning of the contemporary Indian city-space involves an urban apartheid where the state has abdicated any responsibility to the commons”. See “Writing the City and Indian English Fiction: Planning, Violence, and Aesthetics”, Planned Violence ed. by Elleke Boehmer and Dominic Davies (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018) , 206.

[11] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 97.

[12] These poems were later titled his “Kala Ghoda poems” and published posthumously in a collection by the same name. See Arun Kolatkar, Kala Ghoda Poems 1st ed (Mumbai: Pras Prakashan, 2004).

[13] See “Breakfast Time at Kala Ghoda”, Arun Kolatkar: Collected Poems in English, ed. Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, (Blooodaxe Books, 2010).

About the Author

Avani Tandon Vieira is a curator, archivist, and PhD candidate in Criticism and Culture at the University of Cambridge, where she is supported by the Gates Scholarship. Prior to beginning her doctorate, she received a bachelor’s degree in English at St. Stephen’s College, Delhi and a master’s in World Literatures at the University of Oxford. Avani’s practice is focused on minority expression, transnational exchange, and the public humanities. Her academic research considers independent publishing and global modernisms in the twentieth century, with a focus on material histories of the urban. She is interested in the politics of documentary practice, cultures of self-organising, and the relationship between space and form.

From Chapati to Bread: Of New Dietary Belongings

AUTHOR

Sakshi Dogra

Eating food that is not prepared at home is a significant kind of eating that has risen with the growth of restaurants and cafés (Bhatia, 2022). While family meals are an interesting situation allowing us to study the relationship between food content and social setting, equally important are other situations of eating such as snacking, eating alone, eating away from home, and eating informally. Food eaten in the privacy of the home has received much attention and animated a long and rich tradition of analysis on the axes of class, caste, race, gender, and sexuality (Malhotra, Simi et.al., 2021). But it is interesting also to see how food reconfigures public space. In that vein, it remains to be answered whether public edibility brings with it feelings of release and autonomy. This essay will closely analyse Salman Rushdie’s non-fictional work ‘On Leavened Bread’ to trace the ethos determining contemporary eating-feeding relations. I conclude by maintaining that in urban public alimentary culture there is a disavowal of nostalgic culinary identity.

Rushdie’s writings, taking up themes of exile, alienation, and cultural identity, are crucial to the corpus of Indian Writing in English. The particular prose narrative ‘On Leavened Bread’, when looked at specifically through the lens of food and taste, tells a story of new dietary belongings and affiliations, in the context of a porous and globalised world. Here, the representation of food is not about any given predisposition or inclination to local food peculiarities such as chutney and spices which otherwise abound in Salman Rushdie’s oeuvre. In this piece, it is the globally standard leavened bread that captures the Indian-born British-American novelist’s imagination.

In the text, Rushdie confesses his love for leavened bread. He begins the narrative by furnishing his disdain for the “real”, local breads such as phulka and chapati. He finds them completely bland. He is equally critical of the leavened breads he finds in Mumbai which, as he tells his readers, are “dry” and “crumbling”. Rushdie’s search comes to another disappointing halt when the breads he finds in Karachi also prove below par. It is only when he reaches Britain that he finds his model leavened bread. Very slowly and subtly, Rushdie unravels this scene of finally finding the ideal bread and the experience of tasting it. The piece captures his encounter with restaurants and bakeries in London, a space where learned values and practices are contested, where he chooses to act on his desire to consume leavened bread, departing from the secure flavours of home.

The anecdote goes on to demonstrate how a novel sensory experience of eating bread mobilises in Rushdie a desire to visit bakeries and abandon chapatis:

“Then aged thirteen-and-a-half, I flew to England. And suddenly, there it was in every shop window. The White Crusty, the sliced and the unsliced. The Small Tin, The Large Tin, the Danish Bloomer. The abandoned, plentiful promiscuity of it. The soft pillowy mattressiness of it. The well sprung bounciness of it between your teeth. Hard crust and soft centre: the sensuality of that perfect textural contrast. I was done for. In the whorehouses of the bakeries, I was serially, gluttonously, irredeemably unfaithful to all those chapattis-next-door waiting for me back home. East was East but Yeast was West” (4).

This sensorial representation shows that leavened bread becomes a whole world for Rushdie, a total social fact deriving from affect. Given that the places or habitual geographical coordinates that the author is predisposed to are also rendered expendable by virtue of this encounter. It is only the taste and the feeling of the leavened bread that matters, its crusty, pillowy and bouncy texture. This taste and feeling of the bread animates the refutation of the integrity of the family unit represented in the rejection of “chapattis-next-door waiting for me back at home” and a subsequent affirmation of the autonomy of actions and identity.

Rushdie finally insists that bread “be part of daily life”, because “you want it to be there” —the taste and feeling of bread, discovered in this new context, yield a certain sensory shift for him, evoking a desire for the routinization of its consumption. Not just that; Rushdie’s rather concise account of his attachment to not just bread but also bakeries focalises the role of restaurant environments and the desire for their omnipresence.

Rushdie employs the metaphor of the “whorehouse” to encapsulate the often transgressive, licentious and unrestrained nature of eating-out establishments. This playful figurative expression shows that situations of dining out allow for interaction between humans, objects, and affects that collectively moulds consumption behaviour. This is to say that the look and feel of the environment of the restaurant (much like the taste and feeling of the bread) allows the eating public to think with their bodies and in the process sensuously realigns them. The significance of ambience and atmosphere in eating out experiences, therefore, gestures at a transformation of tastes.

Restaurants, cafes, and other spaces of dining out have become a common feature of urban lived reality. They make a small world possible, moving past traditional ways of being. The changing landscape of eating spaces, along with situations and scenes of eating, shows the increasing ordinariness of restaurants and their potential to create new worlds which can be free of traditional cultural affiliations. In conclusion, this short essay tries to argue spaces of eating-out are capable of generating new intuitions and new kinds of gastronomical affinities. Such new dietary belongings and fidelities, as Rushdie’s piece shows, are significant in their disavowal of nostalgic culinary identity and in the creation of post-ethnic affiliations and worlds.

Bibliography

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press, 2010.

Bhatia, Anjali. “The Journey since 1947-IV: Eating Out Comes of Age in India”. The Indian Forum: A Journal-Magazine on Contemporary Issues. https://www.theindiaforum.in/history/journey-1947-iv-eating-out-comes-age-india. October 18, 2022.

Highmore, Ben. “Bitter After Taste: Affect, Food and Social Aesthetics”. The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke University Press, 2010, pp. 118-137.

Highmore, Ben. Ordinary Lives: Studies in the Everyday. Routledge, 2011.

Highmore, Ben. “Taste as Feeling” in New Literary History, vol. 47, no. 4, Autumn 2016, pp. 547-566,

Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/nlh.2016.0029.

Malhotra, Simi., Dogra, Sakshi., & Sharma, Kanika. Food Culture Studies in India. Consumption, Representation and Mediation. Springer. 2021

Mol, Annemarie. Eating in Theory. Duke University Press, 2021.

Rushdie, Salman. “On Leavened Bread”. A Matter of Taste: The Penguin Book of Indian Writing on Food, edited by Nilanjana S. Roy. Penguin Books, 2004.

About the Author

Sakshi Dogra currently teaches English literature and language at Gargi College, University of Delhi as Assistant Professor. She is simultaneously pursuing her Ph.D. research titled “Food, Feelings and Flavors: A Study of Contemporary Indian Writing in English on Food” wherein she seeks to bring out a synthesis of affect and taste through an analysis of an indispensable consumption practice of ingesting food. She is broadly interested in affect theory; study of moods and atmospheres; emotions, feelings and their function in constituting people and cultures. She is the co-editor of Food Culture Studies in India: Consumption, Representation and Mediation and Inhabiting Cyberspace in India: Theory, Perspectives and Challenges, both published by Springer Nature. Her forthcoming co-edited collection of papers titled Affective World Making: Routing Planetary Thought is to be published by Routledge, New Delhi, India. Sakshi has presented papers in national and international conferences on the subject of food.

The Social Life of Food in Indian Cinema

AUTHOR

Shirin Mehrotra

In The Lunchbox (Dir: Ritesh Batra), a 2013 Hindi film about an epistolary romance in Mumbai, a series of montages shows the lead character Ila cooking a host of dishes. Not for her husband, but for a man called Sajan Fernandes who she only knows through letters exchanged via wrongly delivered dabbas meant for her husband. In cooking, Ila finds refuge from her loveless marriage and from a husband who doesn’t even notice that he’s been delivered the wrong lunch. The shots of her dexterous hands tying a thread around a stuffed bitter gourd and shaping soft paneer into kofta, show the love and precision in her cooking.

In contrast, the cooking montages in the Malayalam film The Great Indian Kitchen (Dir: Jeo Baby, 2021) convey the monotony pervading the life of an Indian housewife whose day revolves around cooking for and cleaning after the men in the family. Cooking in this film doesn’t exude love: it highlights systems of oppression precipitating in frustration and simmering anger.

For the most part, food has not played an active role in the narratives of Indian cinema. And on the off chance that it features in a film, it is used to show a woman’s dedication towards her family or the man she’s in love with. However, in recent times, filmmakers are conversing more through the act of cooking and eating. Films across Indian languages now weave in aspects of liberation, caste discrimination, desire, and power into the narrative, and they do it through food.

The politics of a domestic kitchen

Our cultural conditioning has led us to believe that the kitchen is a woman’s domain. Often in Hindi cinema, cooking has been used as a way to show the taming of a shrew – a once-‘modern’ girl running out of a kitchen wearing a saree is a popular narrative; remember Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Bawarchi (1972)? The domestic kitchen is then portrayed, with a certain nostalgia, as a gendered space.

Neeraj Ghaywan’s Hindi film Juice (2017) breaks that nostalgic lens. The short is set in a middle-class home in small-town India. A get together is on – men sitting and chatting comfortably in the living room in front of an air cooler, drinks in hand, while women huddle around the hot and humid kitchen, making dinner. It’s a scene right out of the life of most upper-caste, middle-income Indian families. The film doesn’t just focus on the gendered division of household labour – the men crack casual sexist jokes, show their support towards right wing politics, and, in a scene where one of the women guests pulls out a steel glass to pour chai for the domestic worker, Ghaywan highlights the everyday casteism that is rampant in Indian homes.

In Chaitanya Tamhane’s Marathi film Court (2015), a scene from the domestic life of the public prosecutor subtly illustrates the experiences of a working woman expected to juggle her professional and personal life without much help. Both husband and wife work a nine-to-five job. But the husband comes home and sits in front of the television, while the wife changes, freshens up, and heads straight to the kitchen. The rest of her evening is spent there, cooking dinner for the family. But unlike Court, Juice ends with an act of defiance. Manju, the woman of the house, picks up a chair and drags it to the living room, placing it right in front of the air cooler. She sits down, aware of the discomfort this act of hers has caused the men, and drinks from her glass of orange juice.

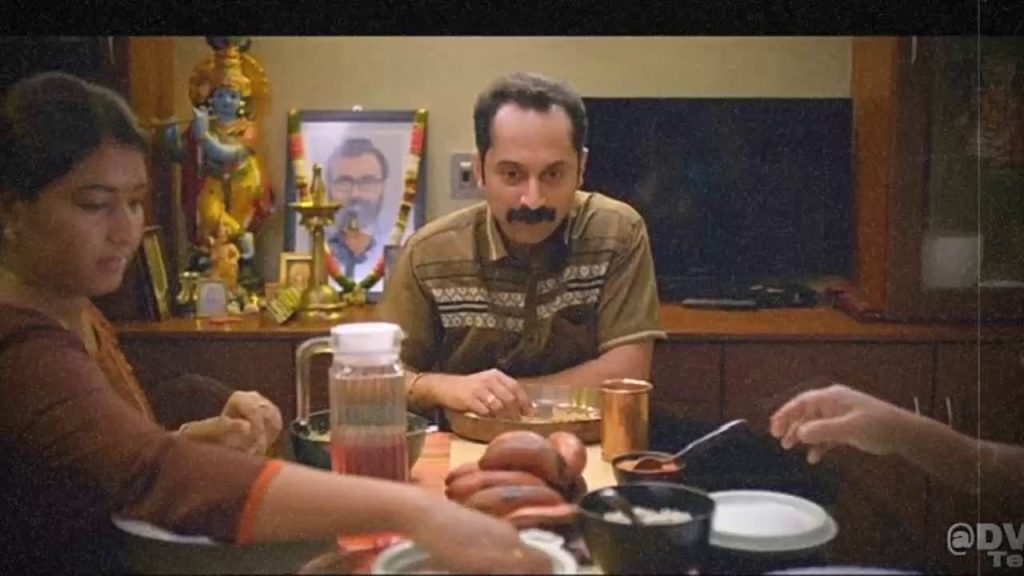

As opposed to the films exploring the relationship between food and gender by looking at the oppression of women in domestic kitchens, the Malayalam film Kumbalangi Nights (Dir: Madhu C. Narayanan, 2019) portrays the performance of masculinity in relation with food. Shammi, who shares the house with his newly-wedded wife, her sister, and mother, assumes the position of the family patriarch; he subtly moves his chair to the head of the dining table as he invites the rest of the family to sit and eat around him. He’s a ‘man’s man’ and in his world, women are mere second-class citizens. In total contrast, Saji who has shared a dysfunctional relationship with his half-brothers so far, cooks and shares meals with his real as well as adoptive family (his dead friend’s wife and his half-brother’s girlfriend) and assumes the position of nurturer as he begins to let himself be vulnerable. The film shows two forms of familial commensality, one authoritarian and the other egalitarian, both mediated through dining practices.

Cooking can often be an act of vulnerability. In a poignant animated Bengali short Maacher Jhol (Dir: Abhishek Verma, 2017), a young man decides to come out to his father by making him his favourite Bengali-style fish curry – a need for acceptance wrapped in an act of care.

Prejudiced foods and caste politics

Where popular Hindi cinema has shied away from conversations around caste, regional films have been more vocal and have used the cultural significations of food to bolster the narrative. In Malayalam director Lijo Jose Pellisery’s films, meat becomes the main character. Both pork (Angamaly Diaries, 2017) and beef (Jallikattu, 2019) are taboo meats for upper-caste Hindus and an important part of the diets of the lower castes. These meats are also intrinsic to Kerala’s food culture and, by making them part of the main narrative, Pellissery asserts the notion of India as a meat-eating country, against Brahmanical projections of ‘purity’ and vegetarianism.

In the Tamil feature Koozhangal (2012) director PS Vinothraj goes a step further to showcase the relationship between extreme marginalisation and food. In this visually captivating film, we see a family living on the peripheries of society, feeding on rats that they skilfully capture and roast live on fire. And we see Ghaywan’s depiction of everyday casteism – separate utensils for Dalit and lower caste guests – once again in his recent Hindi short film Geeli Pucchi (2021).

In the Hindi/English film Axone (Dir: Nicholas Kharkongor, 2019) we see the ways in which the mainland others the food eaten by adivasi communities in India. Axone (pronounced akhuni), a staple food of the North East, has been a major reason for conflict in student accommodations and residential areas in Delhi where a large number of North-Eastern migrants reside. The fermented soybean paste, when cooked with pork, produces a thick aroma, causing much prejudice around the dish and the food of the region at large. The film highlights this prejudice through the story of a group of migrants living in Delhi’s Humayunpur area. There’s an overt burden of shame and guilt that the protagonist experiences as she attempts to make axone for her friend’s wedding ceremony. A similar emotion is captured in Kaaka Muttai (Dir: M. Manikandan, 2015) where the mother is ashamed because her sons eat crow eggs stolen from the bird’s nest: coming from extreme poverty, the kids do not have access to chicken eggs and rely on kaaka muttai (crow eggs) to “get stronger”.

Dishing desire

Food for long has been a vehicle for expressing desire, whether through the written word or the visual medium. But in Hindi films, food has largely been used as a metaphor to sexualise the female body in “item songs” – main toh tandoori murgi hoon yaar gatka le saiyan alcohol se in Dabangg 2, hai hai mirchi in Biwi No. 1, to name two instances. Rarely has a film deployed food as part of the main narrative to explore desire. The Assamese film Aamis (Dir: Bhaskar Hazarika, 2019) does exactly this and stretches the inquiry to darker lengths. A young food anthropologist (Sumon) and a married doctor (Nirmali) find intimacy through shared meals. As their meals get more adventurous and exotic – from rabbits to bats to human flesh – their intimacy grows, blurring the line between pleasure and pain, two sides to the same coin. In 1991, Satyajit Ray explored the idea of cannibalism through a conversation in his film Agantuk. Manmohan Mitra, a wanderer, who is visiting his niece after decades, says that he’s heard about human flesh being tasty but hasn’t had the good fortune of tasting it. Hazarika’s Nirmali then completes the unsatiated hunger of Ray’s character.

From using food to portray economic inequality in a newly independent India – think Do Bigha Zamin (1953) or Roti (1974) – to painting the kitchen in nostalgic shades that bolster the constructs of a ‘good wife’ and an ‘ideal family’ – Bawarchi, Hum Saath-Saath Hain (1999) – to now exploring the modalities of gender, caste, identity and desire, popular Indian cinema has come a long way. And while we’re far from making a Tampopo (1985), where food acts as a core device enabling the interrogation of multiple themes, this is still a big leap that bodes well for the future of Indian filmmaking.

About the Author

Shirin Mehrotra is a food writer, researcher, and anthropologist from India. She writes about the intersection of food, society, culture, and cities and their foodscapes. Her work has been published in Whetstone, The Juggernaut, Conde Nast Traveller, Nat Geo Traveller, Roads & Kingdoms, Feminist Food Journal, HT Brunch, Indian Express, and The Hindu, among others.

A Table for One, Please

AUTHORS

Shroff and Levine

It was many moons ago that I had said those words for the very first time. What had then been a herculean quest, of walking into the Odeon cinema on the corner of New Street, had my young voice quivering at the moment of getting popcorn, my knees cold as I sat facing the screen in the dark. I no longer recall the film, yet I vividly remember the thudding pace of my heartbeat charging and changing in those 90 mins. I had mustered a sense of independence in solitude, and coming out of the physical and metaphorical darkness, an emancipation in these words: “A table for one, please”. I am not the first. Many women have written and staked their claim on this sequestration and in my resonance, I affirm and dance to this silent tune that plays over and over again.

There is a stark difference between eating, as I am now, toast and honey, on the floor of my bedroom, lit by a London-summer sun beam, in my pyjamas with my laptop on my lap, and eating in public. This privacy allows me to act in a way that I simply would not in a restaurant, cafe, bar or on a bench. Being in my ‘pj’s’ for one, but also the casual choices with what and how I am eating. Crumbs spilling onto my chest, me not politely shooing them away, rather wiping my hands on my thigh as some honey has stuck to my fingertips. I am the queen in my parlour eating bread and honey!

This action shows, somehow, my lack of care for my personal time. I can eat and write, why stop to fuel? I can fuel and press on. Time is important, deadlines are the priority, I am a woman and we are famous for multi-tasking – just look at me go. I am, at this moment, both King and Queen:

The King was in his counting house, counting out his money, the Queen was in her parlour, eating bread and honey….

But take this act of dining on one’s own beyond the domestic space. To dine on one’s own in public! It’s become something different, it is performative, it is somehow for others, and it is not something everyone (and sometimes even I would feel able to do.

We asked our Moms if they had ever eaten alone in public. One responded with a resolute “no, why would you?”, while the other answered “no, but I would”. Feeling like you could and actually doing it are very different things. I would need a certain confidence and self-assurance, and a want to spend that time with myself as my main companion. This is hard as sometimes you are the last person you want for company — trust me, I don’t always want to converse with my judgmental inner monologue. It is not everyday that a certain playfulness shows up as my partner-in-crime.

And as women, whether alone or accompanied by good and bad shoulder-angels, I know I will be looked at and understand that I will be confronted with the question: ‘for one?’ A question carrying the weight of societal baggage that is certainly not any angel’s bequest.

Why is she alone? Is she an outcast? Does she have no friends? Where are her children?

I am not the confident man eating alone, or the one who works so hard this is all the time he gets to himself so he feels happy ordering an expensive glass of wine with his steak. I am not the man who knows this space was built and designed for him and is used to being asked what he wants and how he wants it.

No; I am a woman. A woman who is venturing into a world on her own, unchaperoned and independent. I remember an ex boyfriend revealing once that he ‘felt sorry’ for an elderly lady sitting and eating alone. He implied she was one for us to pity. But why? She looked content not putting on a face or trying to impress. The mask fully slipped. Perhaps unlikely to also dust crumbs from her chest. She was bold, abandoned, and at peace.

And so, I dine alone, the world does not quite know what to do with me. It stares. It whispers. I feel those eyes on the back of my neck.

For the last few days, a cloud has hung over my head. This heavy, grey, shapeless mass whose weight equals that of a duvet, under which I pretend to no longer exist. It has been a little over a month that I have had this table for one. Perhaps, such an overwhelming sense of inadequacy was boosted by the condition of being alone, perhaps it was induced by pending work, or could it have been triggered by my inability to read more than a few pages at a time? Of this I cannot be sure, but what is certain is my urgent requirement to blow off the fluff. So I go for a walk.

And just as the whispers take on their own narratives and stories are created for this lone woman, I too am writing on my own — about myself and those I encounter. As if taking advice from Virginia Woolf’s ‘A Room of One’s Own’, we women are fashioning a space for ourselves to create our own fictions. We exist because we do this act. And our imaginations are ignited because we have gifted ourselves this publicly solitary time.

It is not entirely solitary, because there are the small interactions of asking for the table, ordering, nodding thank you when you’ve finished. But mostly you are alone. And in that isolation our daydreams manifest into realities, we are allowed to be whoever we want to be in that moment: a femme fatale, a spy, a woman at peace, an author, an artist, a whiff of mystery…

And within this action, we mentally cleanse ourselves. We confront issues through new eyes, we sit differently using our bodies in new ways, we caress our hair, our hands, our thighs, in different ways. We are no longer that former self, we are ‘othered’ by choice. And that other can be whoever we want them to be, it is powerful and it is unusual. Though it is difficult to get to this euphoric moment of release, of opening up to the new and of discovering oneself, when reached, this moment can be magical.

As this heatwave persists, I pick up a large red umbrella from its corner and plant it over the silver table, amongst the grape vines on the kitchen terrace. I crack the ice tray into a tall iced tea glass, light my cigarette, and settle under the red shade of the parasol on this table for one.

With headphones softly sounding Zakir Hussain and Dave Holland, hearkening back to a concert that I recently heard at Casino Basel, I pick up the book I’m about to finish reading. It is a disappointing verse, taking longer than I anticipated; nonetheless, it is a style of anxious writing that I aspire to. An hour passes: my glass and book are both emptied, yet I am not. I pick up another book and return to my singular table. The red of the book cover is amplified under the rosy shade and my gaze through pink sunglasses. I stare at this arrangement…

Splendid I sit in Matisse’s painting, in his L’Atelier Rouge! I had first seen an image of this painting in a plate stack at the college library some 20 years ago. It had blown me away then, reassuring my faith in drawing from observation. It would be five years later, through an unresolved, emotionally clouded blur, that I would see the painting in its home, at MOMA. Now in my own Rouge, it comes once again as an encouraging reminder. 17 years have had me travel a long way to this table.

Note: All images courtesy of Vishwa Shroff.

About the Authors

Vishwa Shroff is a visual artist. Her practice is rooted in drawing, with a proclivity towards architectural forms that serve as points for contemplation on our relationship with the material world. Her works explore the narratives of lived experience that lay embedded within surfaces. Shroff trained at The Faculty of Fine Arts, MSU, Baroda and Birmingham Institute of Art and Design (UK). She has had eight solo exhibitions and has participated in various artist residencies and group exhibitions. Shroff is the co-director of SqW:Lab and is represented by TARQ.

Charlie Levine is an independent curator working between London and Mumbai. She obtained an MA in Critical and Contextual Art Practices from Birmingham City University (2006). Her key positions include Director, Institute of Curiosity & Curating; Co-Director and Co-Founder of SqW:Lab, an international fellowship for creatives; and Curator of St. Pancras Wires, a new public art project in St. Pancras Station.

Expected Time of Arrival

AUTHOR

Stuti Bhavsar

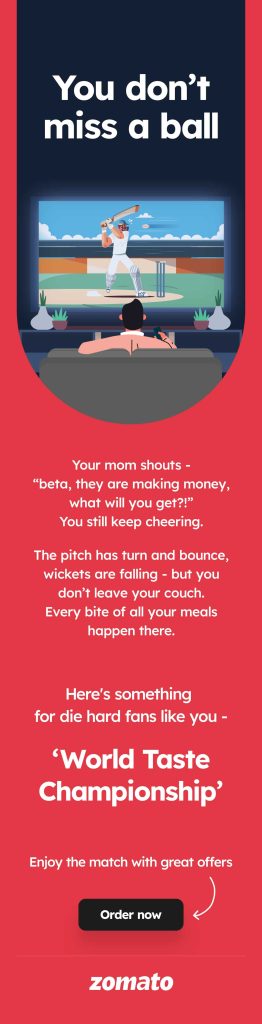

With the promise of promptness, Swiggy was accompanied by other food-based apps on my phone with 10– to 20-minute delivery as their USP – BlinkIt with its compression of time into a blink, BigBasket Now, where the now is conceived as an instance, or Zepto, which announces itself as a next-door neighbour with the tagline of being a last-minute app. Today, time as currency has become the most sought-after metric impacting product valuation[1] and our impulsive consumption behaviour[2], as apps shape our perception of which moments are worth cherishing or missing[3], advising the time-starved to save time and spend time otherwise.

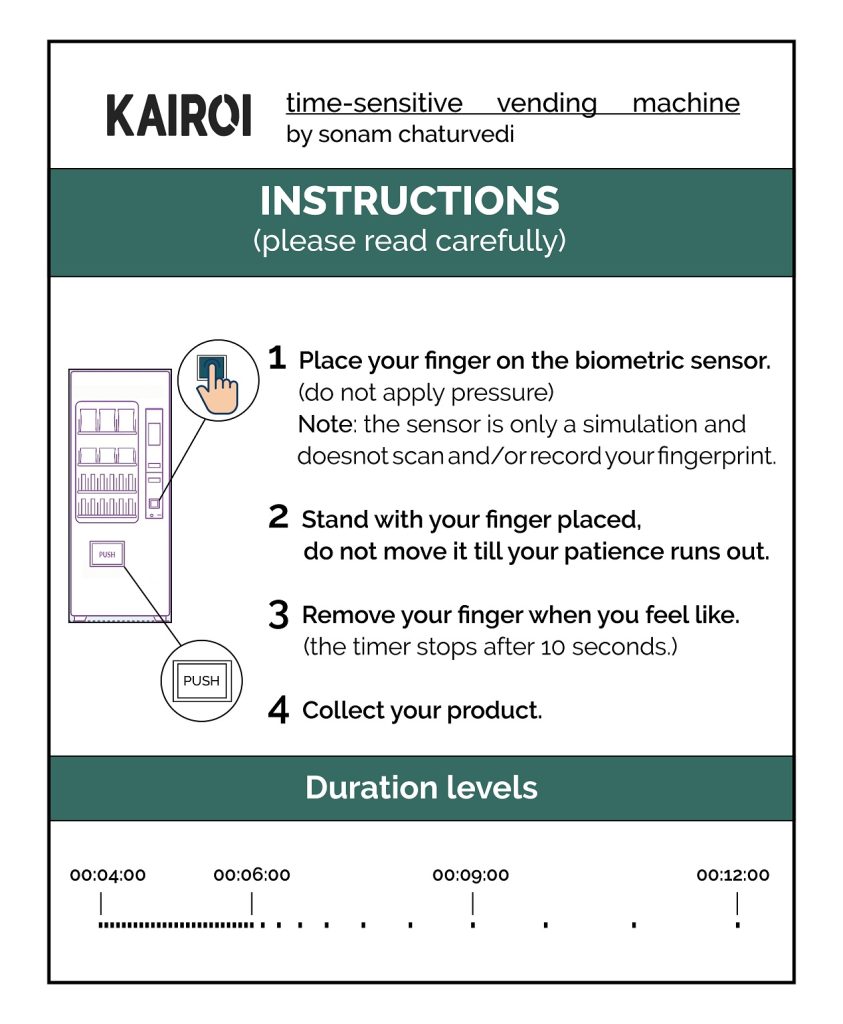

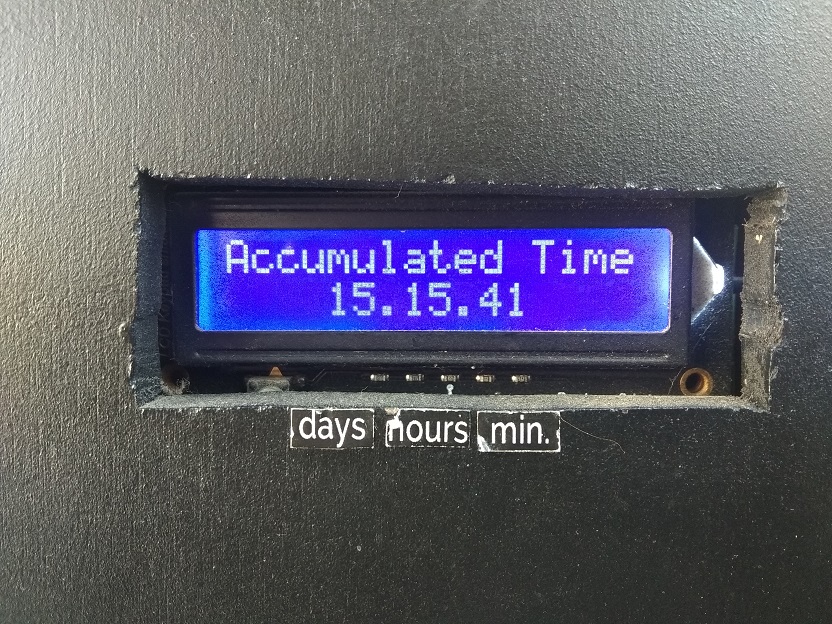

Often located in spaces of transit and stocked with processed foods, vending machines are another such interface—where visuals, marketing, and curated stacks replace the absent store owner and attendant—providing round-the-clock gratification, where convenience is paramount and waiting time is further reduced. Premised on the experiential dimension of contemporary consumption and the ways in which such interfaces shape our dispositions, desires, notions of value, and sense of belonging, this essay looks at Kairoi Times, a time-sensitive vending machine conceived by Sonam Chaturvedi in 2019. Installed near the canteen at Max Mueller Bhavan, Delhi and Kolkata, as part of Five Million Incidents, Kairoi (meaning ‘the times’ in Greek) substituted the monetary value of otherwise free processed food, with waiting time as the currency.

Kairoi at Max Mueller Bhavan, Delhi, 2022. Image source: Sonam Chaturvedi.

Simulating a machine that is commonplace in most urban areas, what intrigued me was Kairoi’s defiance of serving as per expectation, which came to reflect a range of factors that shape our habits, the value we ascribe to processed foods, and the impact it has on the formation of our personal and social selves. With a finger placed on a simulated biometric sensor, the stack revealed familiar but temporally-specific products upon patient gazing. These ranged from Frooti and Uncle Chips, manufactured by Indian industries that were subsumed by MNCs post liberalisation, to imli candies, Natkhat, and Phantom Cigarettes, produced by local small-scale industries, alongside other items in the stack that were manufactured by emerging corporations pre- and post-Independence and which, in many ways, shaped the national consumer imagination.

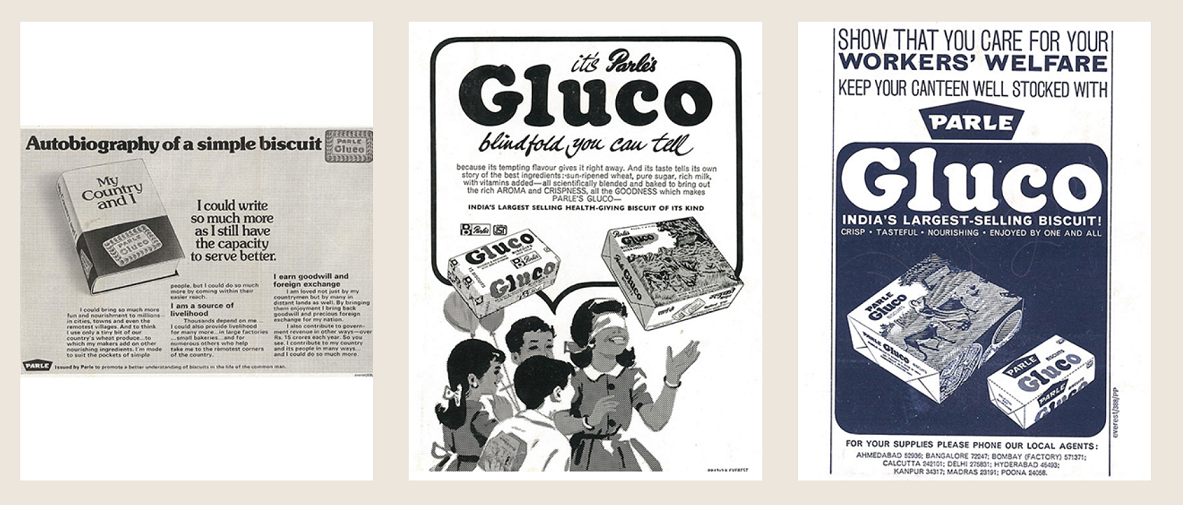

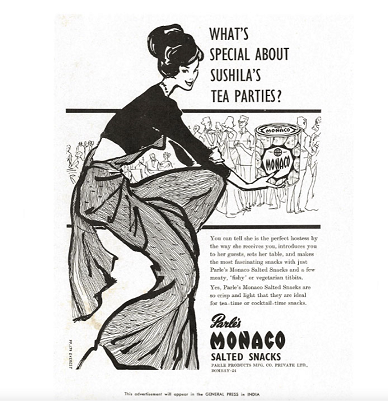

Britannia (Little Hearts, Bourbon) introduced mechanised food production to India and played a key role in supplying biscuits to the British Indian Army during World War II. Parle (Parle-G, Kismi, Frooti, Monaco) was the first Swadeshi confectionery to create affordable Indian alternatives to imported biscuits and candies. Whereas, Nestle (Maggi, Kitkat) was invited by the government to develop the dairy economy post-Independence. In turn, the consumption of products manufactured by these companies became a way to participate in nation-building and serve the values they espoused.

Beneath the products, instead of prices or timestamps, words denoting duration were mentioned, like ‘soon’, ‘simultaneously’, ‘lapse’, ‘longing’, ‘exhausting’, etc. They signified how the computed time didn’t always correspond to its lived experience, where the latter (along with the product’s value) was more often shaped by nostalgia, nutritional promise, access, rewards, and packaging narratives used by corporations banking on hunger.

In a conversation with Sonam on the machine’s refill frequency, it was interesting to note how Phantom Cigarettes with the highest timestamps were refilled faster than Parle-G and Little Hearts, with comparatively lower timestamps. These observations reflect that product values are contextual, and as reminded by Neil Cummings, “… (values) are not properties of things themselves, but judgments made through encounters people have with them at specific times and in specific places.”[4]

Parle-G’s availability on the stack and its relevance[5] for today’s youth reflect the mnemonic value through which the biscuit of the masses—made using refined wheat, once a luxury[6] and now a staple—has endured in the market. While its stable price over the last few decades has sustained trust in the biscuit’s nutritional quality and continual accessibility, its unchanged packaging and tagline have served as tools to aid recollection and nurture collective memories. Heavy on nostalgia, its recent advertisement maintains the latter—with decades encompassed within a minute—where its consumption is illustrated to have impacted historical moments within Indian history, to speak to today’s generation about the processes that have gone into shaping their present self.

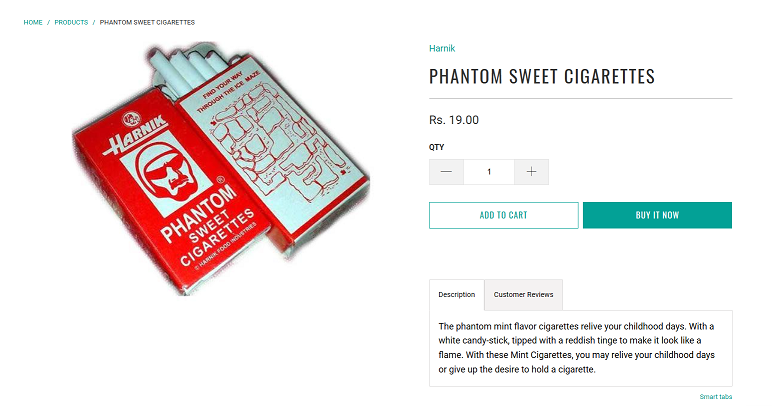

Accompanied by the crowdsourced #YouAreMyParleG campaign, their trademark ‘g for genius’ personifies professional ethics and success stories driven by moral ideals and resilience, where interpersonal care extends to the nation – continuing the brand’s legacy of being swadeshi and creating a certain kind of cultural conscience. While Parle-G’s consumption reflects embodied values that transcend mere habits, the value of Phantom Cigarettes in the stack is rooted in the difficulty of access.

With their form and packaging modelled after real packs of cigarettes, as a candy, Phantom Cigarettes once offered teens the thrill of transgression, where its aesthetic mimesis lent the item a cool quotient and a glamorous value. Believed to entice[7] young adults into chronic smoking as adults, its semi-ban by the government only strengthened the craving for the candy. Seeing people who remember them patiently wait before Kairoi allowed one to observe how this renewed accessibility also led to the reconsideration of the product’s value. In fact, its current availability through online channels very much attests to its survival despite large-scale withdrawal from grocery shops. This was achieved through careful rewording (sticks instead of cigarettes as in the American market) and repackaging (a substitute for those who’ve quit smoking to fulfil their desire of holding a cigarette), which also facilitated their availability at Kairoi.

Sometimes as an alternative to products stigmatised by society, and other times, as a substitute for products that are financially and socially unattainable, many items in the stack employ mimesis of form and consumption experience, where imitation informs their value. Some examples would be the Monaco biscuit (a snack advertised as the life of tea parties, a colonial consumption context later adopted by the Indian elite), Little Hearts (the Indian version of the local French treat Palmier, now synonymous with being a conduit for all kinds of love), Parle-G (a nutritious, affordable, energy booster and supplement), and Frooti (a packaged drink with a long shelf-life, as sweet and fresh as hanging mangoes).

In the past, the consumption of a few of the above products reflected the emergence of an alternative national identity and a neo-elite public sphere that mimicked colonial tastes and consumption behaviours. Being high in sugar, salt, and fat content, these products also form a larger visual and hunger landscape where the preference for processed foods signals a longing and evokes “the desire to be modern but also appeals to a long-standing sensibility which regards fried and sweet foods as luxuries.”[8] Today, however, as Amita Baviskar analyses, the consumption of otherwise elite snacks in small, affordable packages has paved the way, albeit temporarily and sporadically, for the lower classes and the marginalised to participate in a desired and aspirational modernity.[9]

Although the decision of using small package sizes was a technical and operational one within Kairoi, it demonstrates how buying capacity comes to be built, pushing back against the assumption that processed food is accessible to all classes of society at all times. Moreover, with many corporations nowadays aiming at a 10-minute delivery service for a largely urban audience, the work also questions convenience and how it often comes at a cost borne by delivery persons within a largely unregulated gig economy.[10] Additionally, the machine’s wait time leads to a recognition of the labour behind automated and unmanned food interfaces, and who can/can’t afford the time to take a break, pause, and wait, provoking a critical reflection on emergent consumption behaviours.

About the Author

Stuti Bhavsar is an artist, writer, and researcher currently based in Bangalore. Her interests and concerns are rooted at the intersection of the bodily sensorium, the everyday environment in relation to the historical, and the interaction between a part and a whole. She is also invested in seeing how time and labour manifest spatially, physiologically, and in the conditions generated by interfaces – primarily by probing light as a vector.

Stuti did her graduation in Painting from The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda in 2019 and post-graduation in Visual Arts from Ambedkar University, Delhi in 2021. Her essays have been published by organisations such as ASAP|art, Museum of Art and Photography, and Home Sweet Home. Since 2021, she is a copy editor and researcher for Reliable Copy – a publishing house and curatorial practice in Bangalore, dedicated to the realisation and circulation of works, projects, and writing by artists.

Notes

[1]Here, time is meant as delivery time, processing time, and preparatory time, with the latter being quite important within the on-site dining experience.

Singh, Sakshi. “Why kitchen preparation time plays a significant role in food delivery biz”, Restaurant India.in, 2022.

[2] Gent, Edd. “The delivery apps reshaping life in India’s megacities”, MIT Technology Review, 2022.

[3]Through the use of familial, nostalgic, nationalistic, and popular tropes within their push notifications, the apps create an anxiety of ‘missing out’ and mitigate it by providing offers during sports matches, with rewards and discounts during festivals and holidays, or ways one can better celebrate ‘Father’s Day’ with their premium products. Moreover, their everyday personalised notifications around meal times, through wordplay and careful analysis of order summaries, evoke a sense of care and familiarity, where the app purports to remember the consumer’s favourite and check on their needs constantly, just like a loved one would.

[4]Cummings, Neil., Lewandowska, Marysia. “Foreword”, Value of Things, Birkhauser, London, 2000.

[5]However, in the last few years, its relevance—as a product for the masses—for the present youth and whether it will stand the test of time have been questioned. Even as it was marketed as a ‘complete meal’ for migrant workers or as a staple during calamities and crises, the biscuit’s sales have plummeted in the face of competition from other brands with trendier ads, healthier options, and accessibility to gourmet and international range of products (through which one aspires to be a global consumer), with packages drawing upon on more developed reward systems and enticing offers.

Singh, Abhishek. “In a decade or two, Parle will be forced to stop producing Parle-G”, TFIPOST, 2022.

[6]Sinha, Arun. “Why the rich want the poor man’s food”, Free Press Journal, 2023.

[7]Before Harnik started manufacturing Phantom, most of the available candy cigarettes in India were imported. Secondly, the candy’s semi-ban was almost a worldwide movement and so was its later re-packaging and renaming.

Klein, JD., Clair, SS. “Do candy cigarettes encourage young people to smoke?”, BMJ, 2000.

[8]Baviskar, Amita. “Food and Agriculture”, Cambridge Companion to Contemporary Indian Culture, Vasudha Dalmia and Rashmi Sadana (eds), Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[9]Baviskar, Amita. “Consumer Citizenship: Instant Noodles in India”, Gastronomica, 18 (2): 1–10, 2018.

[10]Singh, Karan Deep., Schmall, Emily. “Need an Onion? These Indian Apps Will Deliver It in Minutes.”, The New York Times, 2023.

All references were last accessed on 18 July, 2023.

How Many Lives Does A Fruit Live?

AUTHOR

Shankar Tripathi

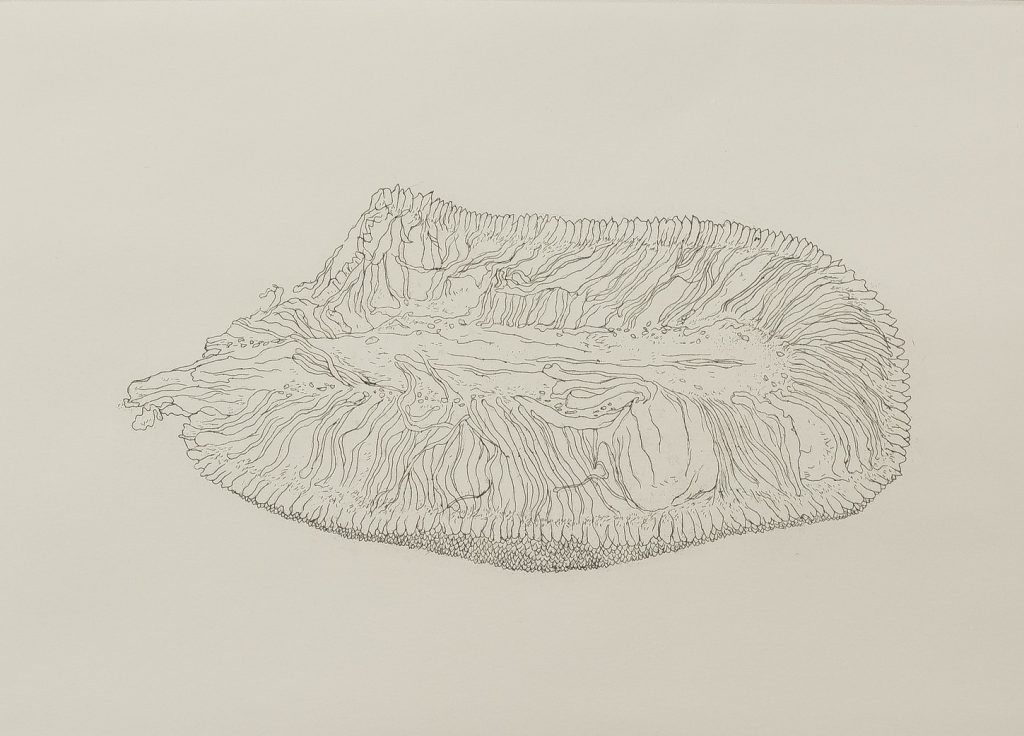

It was always the smell that first caught my attention. A smorgasbord of musky vapours, the room would be filled with its wafting hints of banana, pineapple, and rotten onion. Riveted to the ground, I would find myself carefully examining its cleft parts, wondering how the scent of something so familiar – a fruit that has nourished civilisations for thousands of years (and countless dinner conversations about my nutritional intake) – could feel entirely alien and distant. Ironically however, I found this all-pervasive miasma enchanting as well as nauseating, and remember being mesmerised by it when I first encountered Sajeev Visweswaran’s works.

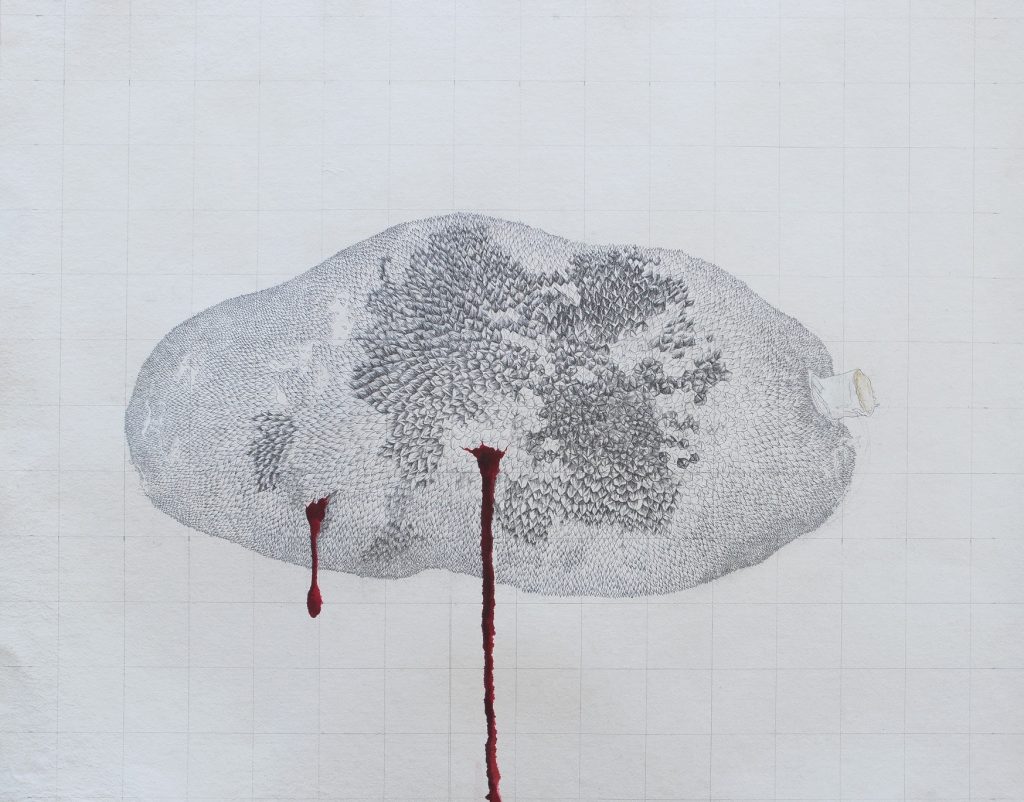

Coming infinitely close to its exposed, fleshy sinews, I saw Sajeev’s hand meticulously trace every rhizomatic connection in front of him, not once leaving the trail of fibrous networks that lay severed from the fruit. His clinically precise lines felt measured and composed, detailing centuries of dietary evolution with delicate profundity. Sajeev’s surgical dissection met no resistance – his pen gliding effortlessly over the paper, registering intricate layers of its reality. In looking at his drawings, I was witnessing his deliberate attempt at removing cells upon cells, noise over noise, till what one was left with was the cleanness of a line.

To look at Sajeev’s works thus meant witnessing his event, a transformative moment in the structure of his work – a deconstruction, if you may – where he bled out colour and context, freeing the object from the grasp of all things temporal and spatial. By his hand, in sieving out the tiniest of bumps and the most wayward of lines, a wholly impersonal, innocuous, and seemingly innocent object was transformed into something real, personally felt, and tangibly appreciated. What I found most interesting was that in observing the universality of his line – its cold, calculative, anatomical estimation – I spectated on the particularity of Sajeev’s experience. His two-dimensional visuality suspended the object, distancing the viewer and yet bringing to the fore the totality of its direct circumstance. I saw his meal, and hungered for my sustenance.

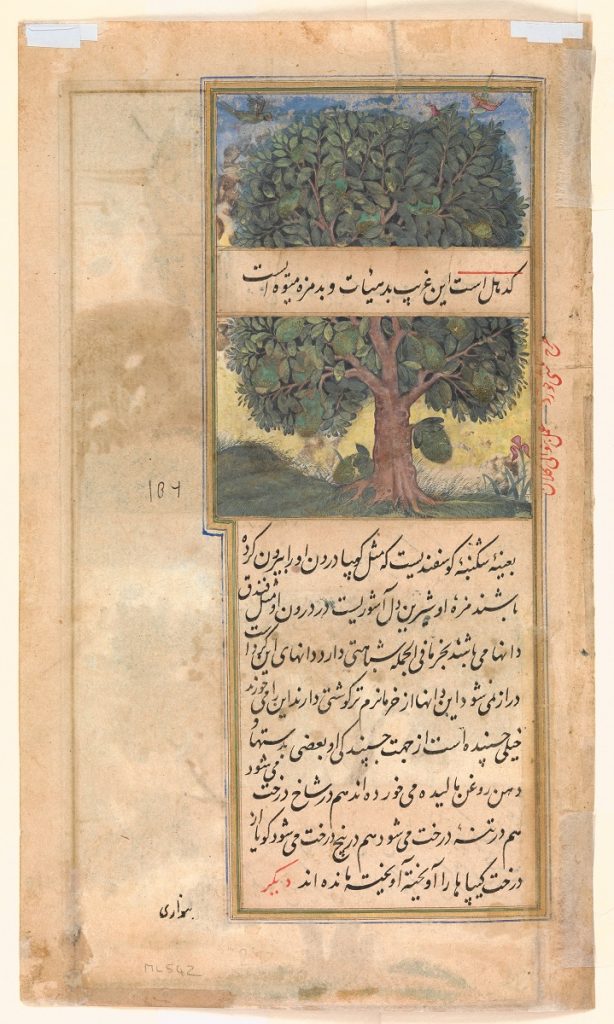

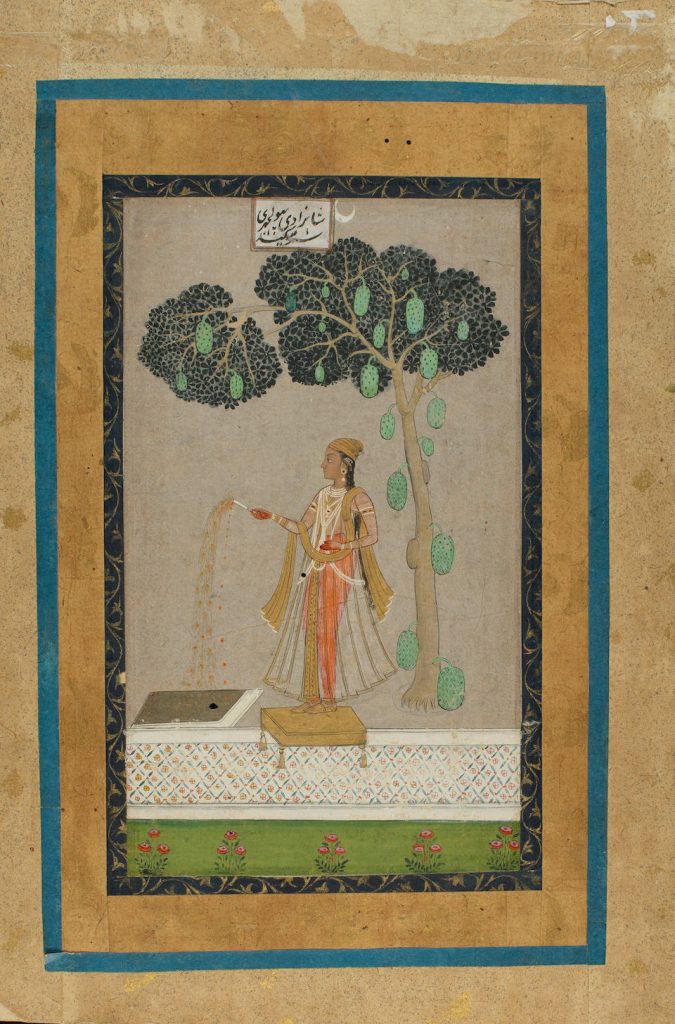

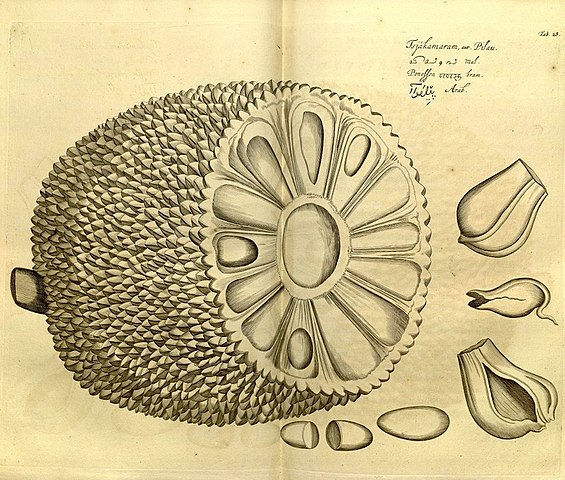

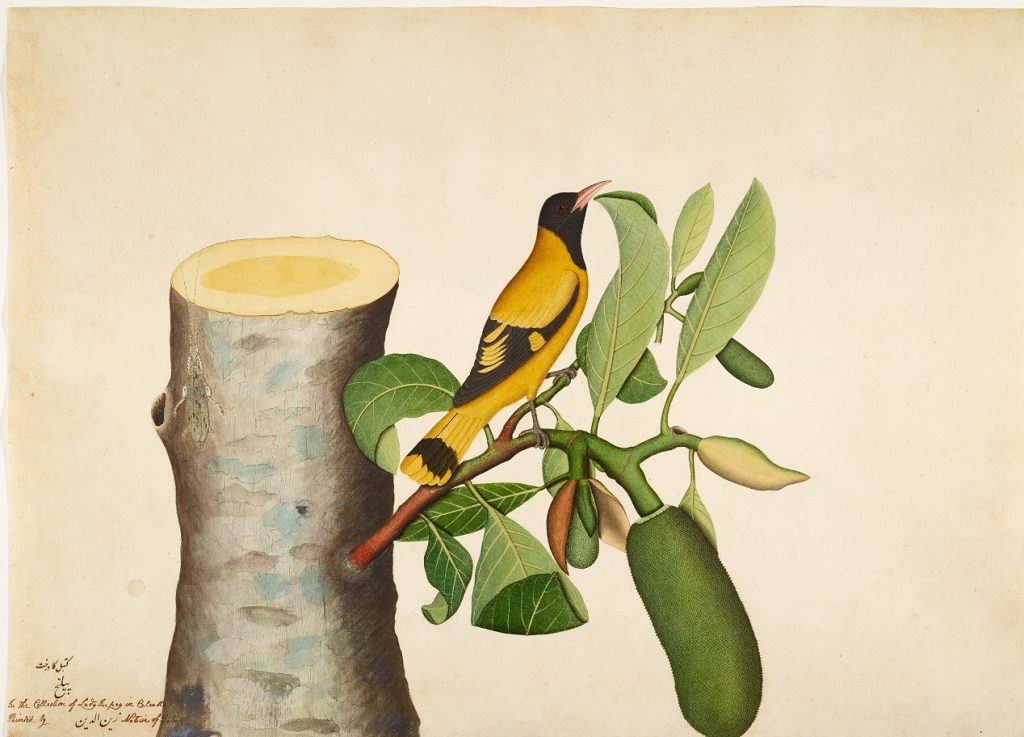

Sajeev’s hypnotic lines are certainly arresting – curiously suggestive yet nonchalant – but this profound punctum[1] introduces an important deliberation on the image he creates. Does his (and by extension, our) intervention produce vigour and movement for an otherwise passive bystander to the process, or is the fruit already animated with a richly-layered history of action and symbolism? I am reminded of a charming folio from 1589 that cuts through this very enquiry Sajeev has introduced. Delicately balancing ink, watercolour, and gold on handmade wasli paper, the royal atelier of the Mughal Emperor Akbar chronicled the subcontinent’s rich culinary heritage in the Baburnama, or the memoirs of Babur. The ornate folio, lettered in the nasta’liq script and abounding with an unparalleled naturalism in colour, style, and technique, captured the gastronomical habits of Genghis Khan’s descendants in regal fashion. In stark contrast with the clinically cold lines of Sajeev, Akbar’s artists visualised a curiosity of the natural world, a marvel of epicurean understanding that provided them with sustenance on and off the battlefield.

What the Baburnama (and other culinary treatises that emerged during this period, like the Supa Shastra from Vijayanagar[2]) did was capture an idiosyncrasy of the land that felt explicit in its excitement. It was celebratory of the soil from which it grew, and tenaciously tender and juicy in the face of scorching elements under the sun. In other words, to see such fruits grow, to live around them, and to eat them in manners hitherto unimagined – was fun. This was a time when every mycelial root spread over the country would gather around with mouth-watering dishes like kothal guti lau pat khar from Assam or panasa pottu kura from Andhra Pradesh (I’m personally more of an appam type of person). No longer mere curiosities, such fruits were venerated, celebrated – regardless of how prickly or unattractive their exterior may be, they were a cause and participant of feasts and celebrations, with ballads sung in their names.

It was only with the arrival of the 17th-century European that our understanding of what we ate changed dramatically. When Dutch settlers captured and studied edible specimens from the Malabar coast for the completion of Hendrik van Rheede’s treatise, Hortus Malabaricus (‘Garden of Malabar’), they produced an academic tome that harnessed such fruits to formulate medicinal treatments exclusively for colonials. The copper plate engravings of the Hortus and the subsequent Company paintings a century later, while perfecting a naturalism of shape and form, considered such foodstuff in a disjointed, aloof, and exoticising manner. Theirs was an academic realism that coldly objectified every minutiae of our reality, recording our gastronomic varieties for the implementation of governance; in precise strokes, modern pigments, and scientific methodology, the art of the subcontinent became a knowledge-building exercise towards the consolidation of Empire. How is it possible that in less than a hundred years, we went from enjoying an abundance of fruity nutrition for everyone, to an imperial system of classification that exercised control over the same?

I apologise if this essay suddenly became a slightly dreary whistle-stop history lesson, but such a provocation is not without merit. When I began ruminating on the visual history of this fruit, I was wholly unprepared for its wondrous and rare – its aja’ib wa-ghara’ib – reality. The totality of my understanding, hitherto this moment, was grossly limited to gorging on spoonfuls of kathal biryani. Therefore, when I saw Sajeev’s works for the first time, I did not simply witness his patient and meditative hand studying a nutritious item of produce – I saw its very potency. It was a potentiality to influence as well as disrupt our understanding of dietary practices; from sensuous and glamorous appreciation by emperors to being tempered by a cold and scientific rationality at the hands of administrators and scholars, I saw a seemingly innocuous and juicy tropical fruit become magical and perplexing across time and space. Sajeev’s canvas was colourless and lacking visual context, and yet rested on a terse history of wonderment, exploration, and conquest.

It is this particularly auratic and characterful history that allows me to wonder just how volatile this fruit is further going to be. There is a large drawing on paper that permits Sajeev to contemplate on an abject reality it would (or possibly, already has) come to inhabit today. His pencil has examined its edible topography, not rushing through a single millimetre of the fruit’s fibrous protrusions, but with an explicit coagulation of conflict and horror. Through a sedate and dignified smear of blood dripping down, the fruit for him is transformed into a sardonic metaphor – a trickster – that is able to define societal attitudes towards culinary agencies. Whether it is contemporary cinema nonchalantly measuring a person’s life against its economic and political value[3], or religious dogma disallowing people from eating it[4], the ‘people’s fruit’ is slowly entering into a disquietude that is deviant and threatening. Perhaps that is why Sajeev’s work seems like it has only been half-bitten; a vessel of anger, filled with blood instead of pulp.

It is entirely possible then, to witness it becoming even more repugnant, an unbearable nausea of banana, pineapple, and rotten onion – or maybe, all we are doing is unfairly blaming a mere jackfruit.

About the Author

Shankar Tripathi is a writer and curator based in New Delhi. Formally trained in art history from Jamia Millia Islamia, Shankar’s graduate thesis questioned the various structures of visuality and countervisuality that informed travel posters and advertising narratives for India during the 1940s-1970s. Focusing on visual and cultural histories, his writings have been featured in spaces like The Punch Magazine, Live Wire, DeCenter Magazine, Indica Today, among others. He was one of the recipients of the Second Young Writers Award in Lens Based Practices (2022) given by Critical Collective and MurthyNAYAK Foundation for writing on Dayanita Singh’s ‘File Room’ series. He currently works with Anant Art Gallery.

Notes

[1]The ‘punctum,’ for Roland Barthes, was that point (literally, a hole) in a photograph or an image that affects the psyche and invokes a response which is more than a casual appreciation – in effect, it is what ‘pricks’ the spectator into appreciating a work beyond its mere formal beauty. See Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982), 94-96.

[2]Colleen Taylor Sen, Feasts and Fasts: A History of Food in India (New Delhi: Speaking Tiger, 2016), 168, 170.

[3]A major plotline in the Netflix film Kathal (dir. Yashowardhan Mishra, 2023) is the disappearance of a lower-caste woman, whose investigation is stymied by the local MLA’s call to divert all security resources in finding his stolen jackfruits.

[4]Strict codes of Jain vegetarianism classify the jackfruit as abhkashya (literally, ‘not worth eating’). Its milky sap is seen as the bloodline of the plant, and by cutting or plucking the fruit, Jains believe that the living organism is killed – motivating a strict abhorrence of the act.

Shokher Ilish : Of Nostalgia, Nation-States, and the Cultural Connotations of Food in Zones of Conflict

AUTHOR

Ankita Ghosh

Two weeks into the Russian invasion of Ukraine, contemporary artist Zhana Kadyrova was one amongst thousands of Ukranians who had no choice but to flee their homes in search of safer horizons. While her family moved westwards to Germany, Kadyrova built a temporary home in the Transcarpathian region. Surrounded in safety by the Carpathian Mountains that separate the hamlets in the region from mainland Ukraine, the mountain rivers, their cleansing water and the large mounds of stone over which the water ran captivated the artist’s imagination at first sight. From this emerged Kadyrova’s project Paliantysia (2022). A symbol. A tool of defense. A shibboleth.

Palianytsia, the humble hearth-baked bread that has symbolised Ukrainian hospitality for thousands of years, became a mechanism to distinguish the enemy from a friend during the Ukrainian counteroffensive against Russia. Displayed at numerous exhibitions across the world, it soon became a symbol of resistance and a medium to raise funds for the Ukrainian people and their cause. Presented as an opulent dinner table covered in white and set with palianytsia, ready to be served, Zhanna Kadyrova’s project at the Kochi Muziris Biennale 2022-23 was a cold reminder of the ongoing war, the resultant displacement, and the minuscule quotidian ways in which the current conflict continues to shape the region’s social and cultural life, while our normal lives continue.

Like all moving art projects that prompt us to think further, Kadyrova’s Palianytsia is unique in many ways. Conceptually simple and easy to assemble, it inspires one to think critically around anthropological notions of regional cuisines. For the artist, the creative process was cathartic in many ways. It added to the dialogue around the Ukrainian cause, while giving shape to her own memory of the war. She says,

“For the first 2 weeks of the war, it seemed to me that art was a dream, that all twenty years of my professional life were just something I had seen while asleep, that art was absolutely powerless and ephemeral in comparison to the merciless military machine destroying peaceful cities and human lives. Now I no longer think so: I see that every artistic gesture makes us visible and makes our voices heard!” (Palianytsia, 2022)

Kadyrova’s project – in interrogating the aesthetics of local culinary practices – spoke to my interest in the socio-cultural connotations of what makes it to our plate. In a country with over twenty different regional cuisines, each replete with its own history, food is considered an important element of our cultural milieu. The many-layered saga of the Indian subcontinent – different regional kingdoms that reigned for decades, influx of foreigners who came to establish trade and, lastly, the influence of the colonial powers – is powerfully reflected in food and the cultural connotations attached to some of our most loved dishes in India. However, what is often sidelined is the effect of the Partition on the way food habits, cuisines, and ingredients have come to inhabit our kitchen spaces in the present moment.

This essay is an enquiry into the history and socio-cultural heritage of food, its overlaps with other concerns of our historical present and, in particular, the ways in which food itself becomes a shibboleth, especially in zones of conflict. I localize the inquiry to the partition of Bengal, to conversations around food (particularly fish) as remnants from a land left behind, and the contested belongings that are intertwined within everyday experiences of taste and dietary sensibilities. My grandparents, who grew up surrounded by water in Barisal, Bangladesh, were migrants to West Bengal in post-Partition India. Two-fifty kilometres from home, they sought a taste of the land they left behind in the food they cooked, the neighbourhoods they chose to reside in, and the dialect they would break into with friends and family.

Even today, a trip to a typical Bengali fish market will make clear the distinctions between the dietary preferences of bangals (ones with ties to pre-Partition East Bengal) and ghotis (the ones with roots in West Bengal). Food habits are typically different in ghoti and bangal households. This comes out in the spices used, the balance of salt vs. sugar in curries, the varieties of fish that continue to dominate meals, and much more. But perhaps the biggest issue when it comes to the way Partition has affected our food choices is the contested nature of sourcing the diverse elements that make up our diets. So much so that any first-generation migrant who made the move to newer territory will still have the highest degree of nostalgia for the culinary ingredients of their erstwhile home.

Nothing can capture the tenor of this emotion as well as the conundrum around finding the ilish (hilsa) in present-day West Bengal. The fish, considered to be the queen of the piscine world, is embedded in the context of contested claims on the river and the Ganges delta, which facilitates its growth and reproduction. Over its life cycle, the fish is largely found in the deep seas of the Bay of Bengal. However, it travels upstream towards freshwater to lay eggs in water that is more favourable for breeding. Affected by a number of problems including unchecked water pollution, unpredictable climate and unlawful fishing activities, the lifecycle of the ilish is also plagued by another issue – the dam on the Indian side of the Ganges at Farakka, West Bengal and the subsequent water flow that makes it to the Padma River on the Bangladesh side.

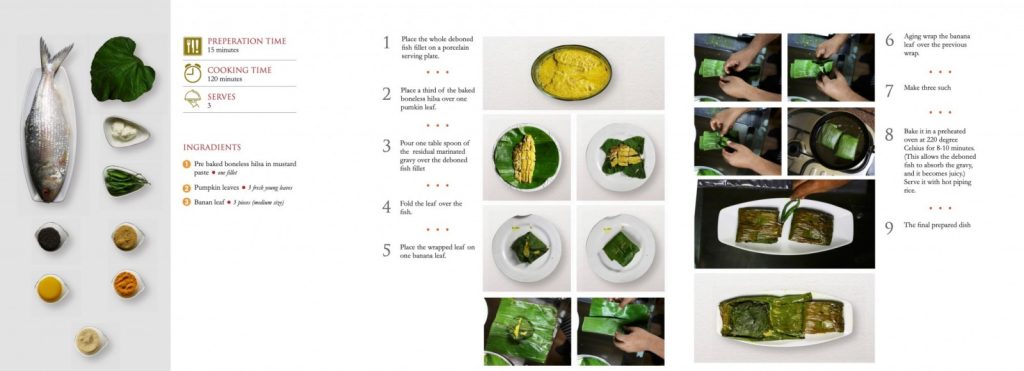

Every year, right from the onset of the monsoons, Bengalis give in to the temptation of the smell of freshly-bought ilish being fried in mustard oil. And the Bangladeshi government under Sheikh Hasina is lauded by the media for sending huge consignments of the fish to India, the majority of which makes it to the Bengali fish markets across the state. Hailed as ‘Hilsa Diplomacy’, this is often seen as a gesture of goodwill to plead for a greater share of the water that makes it towards Bangladeshi territory. Bangladesh, having secured the GI tag, has managed to balance conservation efforts with demands for the fish, which is known for its rich flavour as well as nutritional value. Strict enforcement of regulatory laws on fishing and a ban on sourcing the fish during its breeding season have been in place since 2003. Anyone caught unlawfully fishing for small-sized hilsa before it has had the chance to grow is, therefore, duly punished.

However, such is not the case on the Indian side, where fish markets in Kolkata are flooded with khoka ilish (smaller-sized hilsa) all through the year. The dwindling numbers on the Indian side make it hard to believe that the ilish could once be found as far upstream as the Ganges in Allahabad, 900 kilometres away from the mouth of the river. Meanwhile, the catch has gone up in Bangladesh, followed closely by neighbouring Myanmar. According to the BOBLME (Bay of Bengal Large Marine Ecosystem) – an international partnership involving the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation and governments surrounding the Bay of Bengal – the hilsa industry is worth billions of dollars globally. Given the high economic impact, one would argue that collaborating with neighbouring countries would be mutually beneficial when it comes to river water usage. The impact of barrages and dams should, therefore, be carefully considered, so as to avoid the relegation of the scenario to a zero-sum game policy when it comes to maintenance.

The hilsa is extremely intuitive when it comes to its breeding cycle, and man-made problems such as dredging, usage of mechanised trawlers for fishing, and lack of respect for breeding cycles continue to disrupt the earlier habitats that this fish used to frequent. The Farakka Barrage and the conflict it creates for the hilsa’s free movement upstream is one that affects people on both sides of the border. The reduced fish catch, coupled with the rapid rise in sea-levels along the Ganges delta has seen the migration of several families who have relied on fishing as their primary mode of earning livelihoods. Interdisciplinary artist Pratchaya Phinthong captures the “conflictual reality” of the famed fish in an intervention titled The Hilsa Project (2020), commissioned by the Samdani Art Foundation for the fifth edition of the Dhaka Art Summit. The art installation captures the present trajectory of the fish, which has undergone several changes since the barrage was set up in 1975.

Similar to the way in which Kadyrova voices larger concerns through a simple item that makes up everyday dietary habits, Phinthong makes use of aesthetic interventions to gesture towards geopolitical questions. The hilsa, as it appears in the artist’s work, is no longer just a marker of culinary tastes but rather, a political, sociological, and philosophical marker of a bifurcated Bengal and its people. Phinthong’s image-making is supported by archival material in the form of reconstructed images around the Farakka Barrage, cookbooks that celebrate traditional recipes of the fish from both sides of Bengal, and other objects collected over the artist’s recce around the Ganges delta. Metaphorically making a case for collaborative arrangements between nation-states, Phinthong’s larger body of work Waiting for Hilsa examines the crucial position of the ilish as a geopolitical tool. Through his intervention, he helps create a dialogue on the importance of water as a source of life and underlines the larger socio-cultural identity surrounding the fish that transcends national borders.

The reality that the ilish inhabits today, its precarious future in the face of climate change, and its impact on ecology is a great starting point when it comes to harnessing geopolitics for the sake of sustainability. Regulatory laws that govern fishing should be made wider-focused in order to facilitate cross-country collaborations. The inherent ability of the deep sea to blur boundaries and illuminate porosities can be seen as a positive here. In fact, these concerns over the hilsa offer great lessons in harnessing and fostering socio-cultural collaborations, especially when it comes to countries and regions that share so much cultural history and heritage. One wonders if that is not enough to call for greater interconnections of a socio-political nature, and perhaps, for more humane bonds amongst neighbours. After all, the massive breach in the Russian-controlled dam in southern Ukraine that led to a flood in the first week of June 2023 holds significant lessons. It reminds us of the porous nature of disasters and the damages that the eschewal of collaboration brings to bear upon all of us, as one large interconnected community, beyond the fetters of nation-states.

About the Author

Ankita is a writer based in Mumbai. With a background in media and cultural studies, she approaches art via its intersections with popular culture, political actualities, and dynamics of power. She has previously written for ASAP | art, India Art Fair, Sahapedia, Rashid Irani Young Critics Lab and Youth ki Awaaz. Her work experience in the arts also includes assisting several organisations with design, documentation, communications, curation, and research. She is presently employed with Asia Society India Centre, where she supports arts and culture programming focused on India and South Asia.

Imagined and Lived Spaces of the Queer Kitchen

AUTHOR

Upasana Das

Rukmini Srinivas writes, in Tiffin: Memories and Recipes of Indian Vegetarian Food: “My mother, whom I lovingly call Amma, spent much time and thought in the preparation of the ‘everyday’ tiffin for me and my seven sisters…the tiffin that Amma made, usually one savoury and one sweet, would be a full meal for me. And every day it was a delicious surprise”. The school or office tiffin, most often cooked by our mothers, has been a social marker of class and caste. An entire (sometimes impromptu) community of people gather around individuals with ‘good’ tiffin, and mothers become these figures who must keep producing whatever the child or their community wants.

The kitchen housed in the space of one’s home, carries a certain patriarchal baggage — this is never transferred on to any public kitchens, where the food being unsuitable to one’s taste is not seen as much of a fault or failing. Experimenting with recipes that have been passed down through generations is seldom looked upon as something ideal, as it would interfere with the taste that a family member recalls from years ago. The patriarchal kitchen is a stifling and bone-numbing space, which privileges a certain Stepford-Wife-like mechanised outlook towards cooking — it is only when women step outside of the patriarchal walls of the home kitchen that they are truly afforded the opportunity to creatively experiment with their own culinary interests.

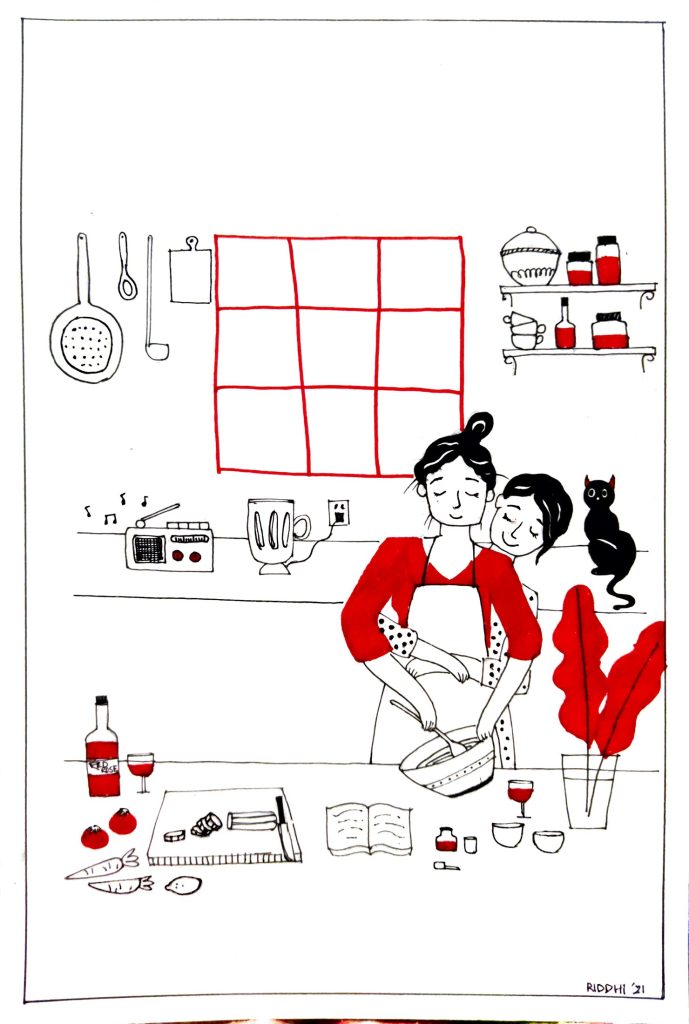

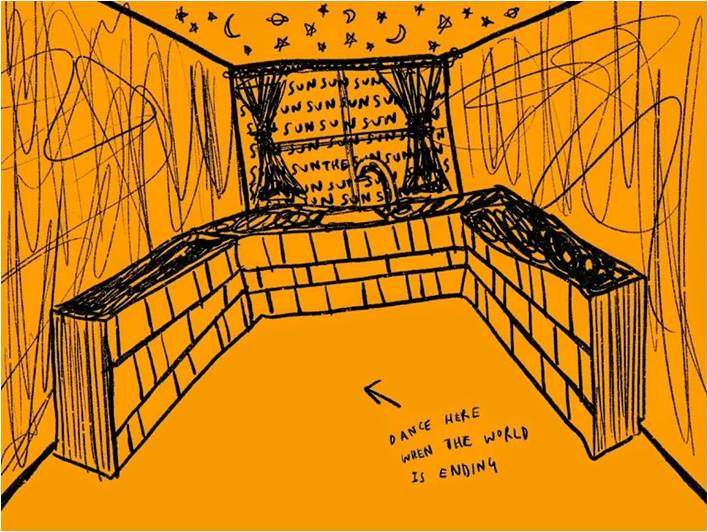

A year after COVID-19, we were working on ‘The Kitchen Studio’ — a workshop by the Museum of Art and Photography (MAP), where we considered the politics of the kitchen, re-imagined spaces, and recalled women’s untold family histories. Meredith E. Abarca writes, in Voices in the Kitchen: Views of Food and the World from Working-Class Mexican and Mexican American Women, about viewing the kitchen as a studio and cooking as artistic expression among women in her community who enjoyed cooking and perceived the activity as empowering. My project partner Jyotsna Ramesh and I then suddenly wondered how queer people had re-imagined kitchens in their own way. What do they dream about when they visualise their ideal cooking space? What kind of community can grow around such spaces? How would labour be thought of in such a context? Anil Pradhan writes that, “in the context of gay food, the process of making food queer and more specifically, the idea of ‘queer kitchens’, play a crucial role in re-presenting, sustaining, and celebrating both queer culinary cultures and queer sexual expression…experimental spaces of culinary cultures have provided consumers, both queer and non-queer, an opportunity to participate in an appreciation of the non-normative through food.” In the 1960s, The Gay Cookbook added playfulness to a range of recipes, which were not presented in bullet points but in rambling paragraphs, bearing the tonal idiosyncrasies of a campy gay man. Written by the chef Lou Rand Hogan, it visualised an alternate space of domesticity and companionship.

I knew a few queer friends, students, and restaurant owners in my city, Kolkata, and I approached them. The kitchen was a place to hand down tradition, said Riddhi, a friend. Sometimes it also becomes a space for companionship “where the domestic help and ‘bahu’ bond over their miseries and where during a gathering, the women can peacefully resent their families,” she said. For her, the kitchen then became a space that accommodated laughter and experiments. Raj, another friend, mentioned how they laughed with Kakoli maashi, who acknowledges her mistakes around the kitchen without judgement: “She cares even though she does not have to. Sometimes I have a stupidly hard time figuring out how to put the milk back in the fridge where everything is crowded but marvellously organised, and she offers to do it for me.” Riddhi recalled sharing work stories with her grandmother and mother while making dessert together in their home kitchen. They recounted how queer friends shared their cooking duties, not overwhelming each other with kitchen work, and taking pleasure in each other’s company while broiling a mean fish. Riddhi also brought up the tendency of mothers to cook what the men or their children want, instead of what they really want to make, mentioning how her uncle would get irritated if food was not cooked in keeping with his tastes.