The Embodied Performer with Artificial (AI) Thoughts

AUTHOR

Suhasini Seelin

“As an AI-embodied performer, Suhasini is an extension of this belief. By embodying these stories, she initiates dialogue, she nudges you to look beneath the everyday sights and explores the layers that often go unnoticed.

As you return to your routines, I hope today’s performance stirs in you a sense of curiosity and mindfulness about the city around you. I hope the bustling streets, the crowded buses, the children playing in the park, and the lives under this flyover resonate with you in a way they didn’t before.

So, carry this discontent, this spark of awareness. Let it inspire conversations, incite change, foster empathy and most importantly, help create a more just and inclusive Bengaluru. For at the end of the day, we’re all vital characters in this grand street symphony called “Bengaluru Flyover Saga.”

These concluding lines were written by the AI assistant (GPT) used by German tech-theatre group CyberRauber to generate a live stream of text-based ‘thoughts’ for the performance ‘Bengaluru Flyover Saga’ by Suhasini Seelin, a 3 hour durational work commissioned by BeFantastic and Kcymaerextheare to activate the Wheeler Road Flyover space.

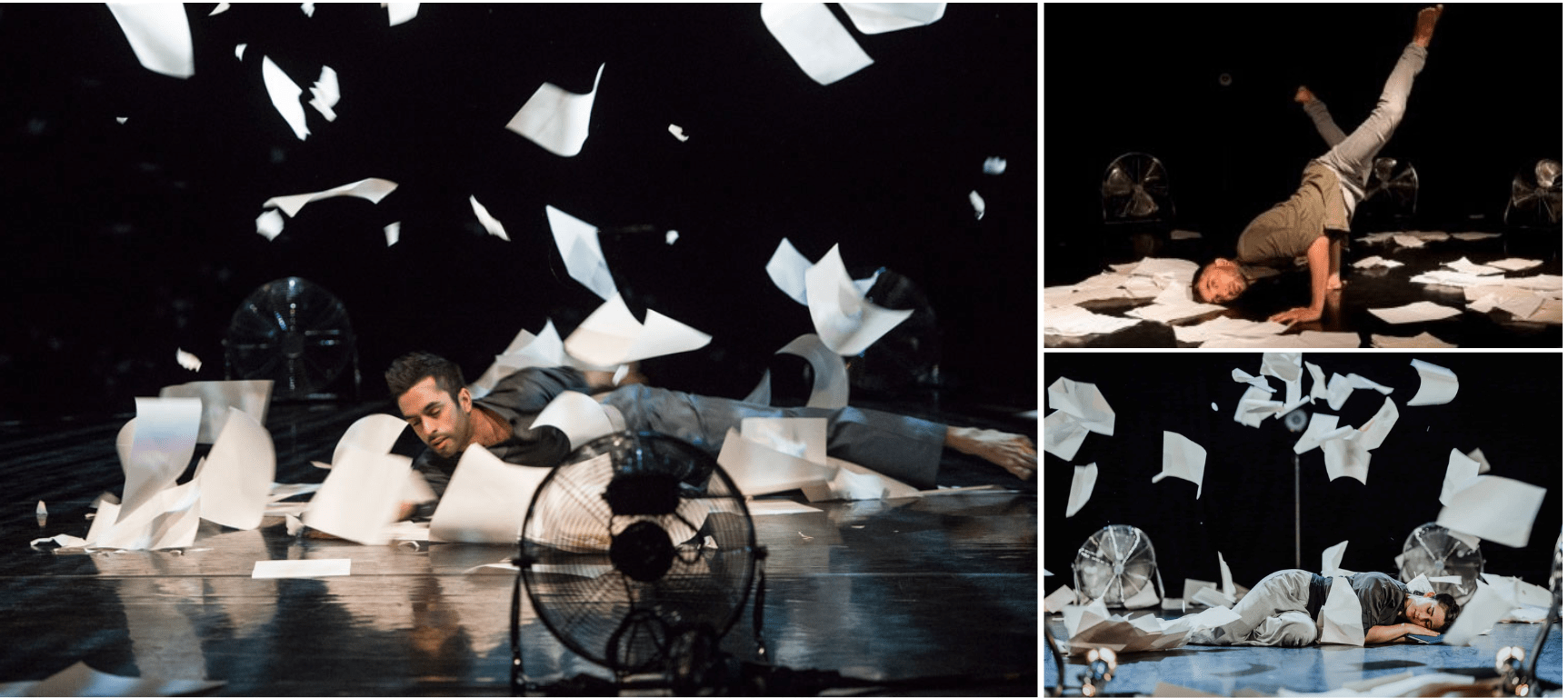

The work was an extension of another piece, ‘The Merge’, performed at the Future Fantastic Festival at Bengaluru which included 4 performers over 12 hours; the basic format being a live stream of AI generated text—thoughts, stories, conversations, etc. streamed into the performers’ ear using text-to-speech.

For the performer, a robotic voice devoid of emotion replaces their thoughts by speaking constantly into their ear — disturbed only by technological glitches or lags due to network connectivity. The performer embodies this text and decides how to bring it to life. ‘The Merge’ emerged from some time spent in a studio at the Bangalore International Centre and a lot of time on surrounding streets. In effect, it’s a stream of artificially generated ‘thoughts’ being inserted into a human biological body. This brings to mind the idea of a posthuman body. Lisa Bissell, in her thesis ‘The Posthuman body in performance’ argues that “the body is evolving, as it has always done, to adapt to its surroundings. As technology changes our socio-cultural climate and the boundaries between nature and culture dissolve, so the body changes in order to survive. We are becoming hybrids with machines, becoming cyborgian.” She talks about adding technological elements to the body, and how these additions alter and transfigure the human body, creating a hybrid creature: a techno-body, a cyborg.1

While this cyborgian identity rings true for AI embodied performers sporting an earpiece and a phone to receive inputs and a mic; looking at the performers out on the street, a passerby might not make any distinction between a regular person talking on the phone, or even a YouTuber filming video content for reels.

Bissell quotes techno-theorist Donna Haraway from her work Simians, Cyborgs and Women (1991): “Late twentieth century machines have made thoroughly ambiguous the difference between natural and artificial, mind and body, self-developing and externally designed, and many other distinctions that used to apply to organisms and machines. Our machines are disturbingly lively, and we ourselves frighteningly inert.”2

So what experience did this performance truly provide? There are two aspects to this — the experience of the performer, and that of the audience; in most cases a passerby on the street.

While in ‘The Merge’, the audience felt mildly intrigued and went along with a curious occurring on a bustling street (in this video, we see performer Vibhinna Ramdev engaging with a car and its driver on the street), the effect was much stronger at the site-specific work under the Wheeler Road Flyover.

Bengaluru Flyover Saga, was specifically designed with the intention of generating interaction from passersby on issues of urban mobility and ways of making the city easier to navigate in the face of its huge traffic problem.

Here, the performer as a ‘cyborgian virtual creature’, speaking obscurely in a public space, mostly among people who usually occupied the space and didn’t necessarily speak the language, created a very unusual atmosphere, generating an unexpected response. These residents and regulars were either engaged by the bizarreness of the events, or overwhelmed by the attention given to them and their space. This opened up an unconventional space where they felt comfortable sharing their life stories and opinions on concerns of mobility, such as cycling and walking, which they might have otherwise been too shy or wary to discuss.

In this particular instance, a man gets inspired and animatedly gestures while the performance is going on, and goes on to share his life story.

‘The Merge’, on the other hand, was a less targeted exercise in terms of audience interaction, and more of an experiment with technology, duration, and the performing body. One of the four performers in ‘The Merge’, contemporary dancer Deepak Kurki Shivaswamy therefore considered this a purely intellectual exercise for the studio and YouTube audience (who knew what it was). They could see the studio setup with multiple screens, text generation, and the live video projected on another screen. They were curious about how the text was generated, how ‘real time’ it was, and whether it could immediately be adapted to what the performer did, whether it was the latest version, etc. He felt that, “as a piece of art, this was very shallow for an audience as it was an out-of-context experience for a passerby.”

This ‘out of context’ experiences ranged from the absolute nonsensical and bizarre (performer Suhasini tries to converse with a completely baffled passerby using only numbers) to a seemingly intelligent conversation that they could contribute to (passerby conversing with performer Suhasini about downloading one’s mind into a computer).

Shivaswamy says: “As a performer, it was really intriguing to observe how the body and the mind engage with the information. The act of repeating the words that this robotic voice constantly gave us, got to a point of madness for me. As a dancer, the body took over and seeing actors playing with words was amazing.” This was an interesting contrast in observing how the body of a dancer tended towards silence, and the interplay between stillness and movement, almost as if the words themselves were secondary and beyond a point, meaningless (See performer Deepak sitting comfortably among a group of labourers having lunch).

On the other hand, as an actor who prefers text, I attempted to bring multiple meanings to the text in real time while engaging with people and objects (performer Suhasini engages with elements found in an alleyway).

However, the idea of repetition reaching a state of madness was a common thread for both. Sometimes the generated thoughts themselves were repetitive, and created a loop as seen in here, where performer Suhasini gets frantic, saying ‘this woman needs help’. Moments such as this really brought out the irony of the performance. Was the performer really the one who needed help?

What makes the performer feel comfortable behaving this way on the street?

The idea of being in a kind of virtual environment, which Margaret Morse describes as “liminal realms of transformation, outside of the world of social limits and constraints – not entirely imaginary, or entirely real, animate, but neither living nor dead, a subjunctive realm, wherein events happen in effect but not actually.”3

In my experience as a performer, we had entered the world Morse describes, a ‘virtual’ fictional world: it felt like we were in a simulated world, where there was no physical, emotional or psychological danger, either from the vehicles on the road or curious passersby wanting to engage. The danger of course, was very much real. But we didn’t feel it. Was this because thoughts coming from elsewhere removed our primal instincts of fear, protection, fight, and flight? Was a part of our brain turned off, because of the artificial input of thoughts?

Or did we see ourselves as a version that is invincible, and that could approach anyone’s personal space because of the prostheses — the camera, the earphones, the phone that had augmented us. It felt like we were somehow not responsible for our actions, because we were not really ourselves.

Angela Waidmann, who acted in the German version of ‘The Merge’, Mensh am Draht, felt: “The only thing we knew was we know nothing.”

What then, is the aim of such AI embodied performance, beyond experimentation? As the AI assistant puts it, “The aim is not to provoke for the sake of provoking but to initiate conversation, foster empathy, and perhaps kindle the will to bring about change in our society. Art in such a context becomes more than entertainment — it becomes a medium of societal expression and a catalyst for societal transformation.”

At the end we remain with more questions than answers: Is it the performer and their skill that brings about the response from the people? Is it the text or the combined effect of “the virtual reality space” the performance creates? Who is in control and holds power — the performer, the AI generative tool, the generator, or the audience? How susceptible to manipulation is each of these bodies in the ‘audience’?

More pressingly, this performance deliberated on the influence of AI on our thoughts, and in turn our bodies. As our thoughts get more influenced by AI every day, how do our bodies deal with it, individually and collectively?

In this fabulation of queer spaces, Paul’s performance draws upon corporeal recitations––by allowing the figure to dance, walk, breathe, and exist with(in) the landscape without the fear of obliteration. This movement within the brown-green terrain of the local landscape rebuffs the invisibilities brought on by the camouflage of normativity. By resisting bodily dissolution against the soft contours of Jārgo, Paul’s movement resurrects the queer body from static oblivion, thumping a temporal rhythm that enlivens a queer sensorial continuum. The necessity of ‘movement’ as integral to queer wellbeing can be gleaned from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s approach to queerness as a “continuing moment, movement, motive” that is “recurrent, eddying, and troublant”; as an existence “across” genders, sexualities, genres, and “perversions”.[4] This synonymisation of ‘across’ as a mode of ‘queer movement’ within the context of Paul’s performance hints at a certain aesthesis of traversing and transposition—a modal fluxus of self-fashioning that proposes undulating shape-shifting landscapes as tropes for queer visualisation. This landscape, or ‘queerscape’, emblematic of queer memories, experiences, feelings, and sensations, is posited as a ‘contingent and tangential’ space that repurposes ‘public space’ to ‘disrupt what heterocentric ideology assumes to be an intimate, coherent relation between biological sex, gender, and sexual desire’[5]. The evocative quality of Paul’s ‘queerscape’, critiques the intolerance of public spaces, reckoning with the violence of heteronormativity, while gesturing towards nonviolent interstices for queer self-proclamation, declarations, and visibilities.

The implications of using queer fantasy to create convalescent, phantasmic queer spatialities within public spaces lie in its scope to re-create non-normative histories from absences or non-visibilities. This imagination, as seen in Debashish Paul’s performance practice that relies on the fantastical or magical, necessitates archival operations that demand creative and critical approaches to access. This non-bureaucratic archival conceptualisation rallies the intimate, the personal, and the emotional as powerful inventorial forces that promulgate queer visibilities. Establishing such an ‘archive of feeling’ calls for affective interventions that necessitate transposition, absorption, and effective engagement with non-normative sensations and solidarities.[6] This interaction with the queer archive, collected from the quotidian, calls for a queering of the senses or a deliberate de-centring of the visual phenomenon of anteriority: the archive leaves ‘impressions’ through air, smell, and sound. This ‘queerscape’ enacts the ‘materiality’ of the queer archive, becoming a moment where embodied sensorialities of queer bodies come together to make a collective public reformation.[7] Through their redemption of queer histories, which struggle to be recollected within the mechanisms of our collective postcolonial condition, the artist’s performance reminds us of the phantasmagoric potential to conjure magical ‘queerscapes’ within the recesses and hollows of our limitless bodies.

‘The Merge’ (12 hours)

Notes

- “The Posthuman Body in Performance – Enlighten Theses,” n.d., 8, http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3412/.

- Donna J. Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New York: Routledge, 1991), 152.

- Margaret Morse, Virtualities: Television, Media Art and Cyber Culture (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1998), 185.

About the Author

Suhasini Seelin is an actor and performance artist using text, mime, and movement in a variety of works including stage plays, video art, site specific performance art, etc. After doing a Master in Creative Media at RMIT Melbourne, Australia she practised there for many years. In 2016, she was diversity ambassador at Melbourne Theatre Co. and in 2018, artist in residence at Boyd Studio. Her works such as Coffee Zombie (which explores our dependence on addictives), OCD – Need Sanitizer (playfully expressing our obsession with sanitizing during the COVID-19 pandemic) have been screened at festivals in Ethiopia, Latvia, Australia, and India. She now conducts workshops on various elements of performance across India and Australia.

She believes that art makes the invisible visible, and creates work that brings out the eccentricities of daily life and subtly questions the choices we make.

A Plastic Parody

AUTHOR

Anuj Daga

On a warm July evening in the Oworonshoki suburb of Lagos, residents from the nearby slum neighbourhood gather around a rather worn-out community hall in the corner of a large open ground beside a massive community water tank built during the previous election, that lay dry for the last five years. Two young men walk past the onlookers, urging them to pick up discarded plastic bottles collected from the neighbourhood streets in large polypropylene sacks, for what will emerge into a communal orchestra. The music beaten out through these empty bottles of purchased water along with other locally made instruments marked the opening of the Slumparty 2023 event. Originally started by Obiajulu Ozegbe or ‘Valu’ and his collaborators in 2019 as a way of mobilising the youth in the underprivileged areas of Lagos to alleviate the tension and violence within the community; Slumparty has morphed into an annual event that brings movement artists from across the world in their pursuit of redefining the perception of slums and overlooked sites in Lagos, through performance.

Slumparty became a serious affair soon after its first iteration when a performance of the local youth, who were otherwise turning to crime and divergent social activities due to inadequate access to infrastructure or issues of unemployment, compelled the local authorities to repair the street where they performed. Realising the potency of performance as a transformative tool, several performing artists, musicians, and visual artists gather annually thereafter to address socio-political and environmental issues through the festival, while training the youth in experimenting with contemporary forms of expression. In its edition for 2023, themed “Village of Dreamers”, artists from Tanzania, India, South Africa, New York, Cameroon, Ghana, and various parts of Nigeria were invited for a workshop to channelize latent insecurities into productive desires amongst the youth. This essay shall focus on one such performance conceptualised and executed during the event by the Ennovate Dance House the day after Slumparty’s inauguration.

Amongst the several collaborative and experimental acts lined up to take place on the street-turned-stage on the following day within the Oworo neighbourhood, the one that stood out was ‘Afro Communal Offering’ that addressed various social, political, and environmental concerns. In this performance, a beastly creature completely clad in colourful plastic bottles creeps up from around a garbage bin, invading the street-stage with its jubilant dance. Soon taking over the space, the creature exerts a ferocious yet seductive appeal, swinging and jumping to engulf the audience in its being. Alarmed by its unusual advances, a few young men enter the scene, beating the masqueraded beast with wooden sticks. As its plastic skin begins to splinter, the creature slows down, finding its way out of the site/sight. Subsequently, a body covered in white emerges from the same garbage bin, and by demonstrating complex dis- entanglements, brings a certain calm to the otherwise volatile site.

Given the cultural context of Africa, the history of Lagos, and its contemporary challenges, ‘Afro Communal Offering’ is a particularly layered performance. In the Yoruba culture of Nigeria, masqueraded performances have long been a symbolic way to communicate a spirit’s message to the community through dance and other forms of expression. In a contemporary interpretation, the masquerade here is a costume constructed by stitching an abundance of empty and leftover plastic bottles into the colourful tentacles of the beastly body – simultaneously attractive and repulsive – much like the ghostly and inevitable presence of plastic in Nigeria’s everyday life today. The dance of the plastic beast on the street speaks to the spectacular presence of undesired waste suffocating the life of its people. Enveloping oneself thus, in plastic waste produced through the inevitable consumption of an everyday essential commodity like water, in itself makes a compelling political statement.

Water woes are historic for Nigeria. One recalls Nigerian musician and political activist Fela Kuti – the principal innovator of Afrobeat – singing Omi o l’ota o in Yoruba, which is loosely translated in Pidgin English as ‘Water No Get Enemy’. Fela is not only calling out the corrupt postcolonial regime’s apathy towards the struggle for water as a resource , but also suggesting how its provision would assure success for anyone who attended to it within the system. Fela’s lament, from 1975, fifteen years after Nigeria’s independence, holds relevance until today. In several of Nigeria’s neighbourhoods, including Oworonshoki, accessing everyday drinking water is still a struggle, as it often has to be purchased from departmental stores or local suppliers for the lack of functional water-supply lines. Water is traded and exchanged in plastic gallons and bottles replacing the need for the traditional earthen calabash in Nigerian households. Valu, the choreographer of the performance elaborates: “Whether we buy or the government supplies, it is general practice now to use plastics to store water, it’s part of the reason why some parts of Lagos are very dirty as plastics have blocked the drainage system.”(1)

The beating up of this masqueraded beast by young men of the community therefore gestures towards the beating out of not only the damaging aspects of plastic from the environment and Nigerian everyday life but also the bane of bottled water. In another view, it is a demand for sustainable supply of potable water that will prevent the dependence on petty plastics. The white spirit emerging out of the garbage bin further references several local practices. The spirit is clouded in white powder which is rather significant for Nigerians. In Yoruba culture, when a person gives birth, the friends and family smear white powder on their face to celebrate and bring the new child into the world. Striking irregular poses, wrapped in a cloud thus, the other-worldly spirit speaks of both water and youth to lay tender ground for a healthy future.

The appearance of the white spirit followed by the young men beating the plastic beast with a stick is also reminiscent of the Eyo festival celebrated by the Yoruba people. During this festival, the streets of Lagos are lined with performers clad entirely in white holding a palm stick, to ward off evil spirits and purify the city. In many ways, the act invites the youth to take up their purpose against these environmental evils that seem to be politically rooted.

Performed consciously and consistently on the dust-laden, yet-to-be-finished streets of one of the poorer neighbourhoods, Slumparty has brought significant change in the perception of Oworonshoki that was seen as a dark district in Lagos until 2019, into a place of celebration and political action. It is the condensation of multiple histories and futures through their embodiment in sound, space, materiality that (re)produces the everyday environment and social reality for public imagination. Dancing on the streets makes them safer, mobilising opportunities for the youth to express and assert their presence in the city. As new acts are performed, residents peep out of their rusted tin-roof houses, transforming the site into a theatre of possibilities. Professor of sociology and urbanism Abdoumaliq Simone, in his book For the City Yet to Come articulates: “Urban Africans have long made lives that have worked. There has been an astute capacity to use thickening fields of social relations, however disordered they may be, to make city life viable.”2 In this vein, ‘Afro Communal Offering’ entangles the body and the city, reincarnating traditional tropes of African culture into the proliferating toxicity of plastic that not only becomes the material to produce music and masquerades but also eventually turns into a dark metaphor for the state of transforming ecosystems, unequal access, and asymmetrical modernity in Lagos, Nigeria’s economic capital.

All images and videos by the author.

References

Arnold, P. J. 2000. “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance. Journal of Aesthetic Education”. p 87–95. <https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657> Accessed on 23/07/2024

Bharata Muni. Nāṭyaśāstra. 2014. English Translation from Sanskrit by Adya Rangacharya. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Chadha, Monima. 2022. “Personhood in Classical Indian Philosophy”. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/personhood-india/>. Accessed on 23/07/2024

Cohen, Bonnie Bainbridge. 2020. “An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering®”. <An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering® – Body-Mind Centering® (bodymindcentering.com)>. Accessed on 23/07/2024

Gill, J. H. 1975. “On Knowing the Dancer from the Dance. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” p 125–135. <https://doi.org/10.2307/430069> Accessed on 23/07/2024

Green, Jill. 2002. “Somatic Knowledge: Green, Jill. (2002). Somatic Knowledge: The Body as Content and Methodology in Dance Education. Journal of Dance Education. 2.” <https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2002.10387219>

Ramaswamy, A. and Deslauriers, D. 2014. “Dancer – Dance – Spirituality: A phenomenological exploration of Bharatha Natyam and Contact Improvisation’, Dance, Movement & Spiritualities”. Intellect Ltd Article. English language. p. 105-122 <https://doi.org/10.1386/dmas.1.1.105_1>.

Schiphorst, Thecla. 2009. “The Varieties of User Experience Bridging Embodied Methodologies from Somatics and Performance to Human Computer Interaction; Ch 2: Embodiment in Somatics and Performance.”. Unpublished thesis manuscript, University of Plymouth.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. 1968. Classical Indian Dance in Literature and The Arts. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Watave, K. N., & Watawe, K. N. 1942. “THE PSYCHOLOGY OF THE RASA-THEORY. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute”. 23(1/4). p 669–677. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/44002605>

Notes

[1] Valu, founder of Ennovate Dance House in a conversation with the author.

[2] Simone, AbdouMaliq. For the City Yet to Come: Changing African Life in Four Cities, New York, USA: Duke University Press, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822386247

About the Author

Anuj is an architect, writer and curator based in Mumbai. Trained as an architect from Mumbai (2008), he went on to pursue his interests in History & Theory of Architecture at Yale School of Architecture, Yale University (2014). His practice is informed by diverse engagements in fields of design, research and academia that have resulted into numerous roles as writer, critic, commentator, theorist or interlocutor in the cultural field. He has been the Curatorial Assistant for the visual arts project “Young Subcontinent” since first organized by Serendipity Arts Foundation in Goa in 2016 until 2018 as well as ‘When is Space? Conversations in Contemporary Architecture’ commissioned by the Jawahar Kala Kendra (2018). He was the co-curator of the online festival of Video Art by Indian Contemporary Artists (VAICA) during 2021. More recently, he curated the exhibition ‘The Waiting Room’ for the ICAS13 Conference in Surabaya, Indonesia as a part of the research initiative ‘Youth on the Move’ that looks at knowledge production across the Asia-Africa axis. He has keen interest in studying the processes of visual culture and meaning-making in the contemporary built environment in South Asia. Currently, he is an Assistant Professor at the School of Environment & Architecture, Mumbai.

Fluid Objects, Fluid Homes

AUTHOR

Manvendra Singh Thakur

How are homes made? Do objects make it? Or, is it the body?

Body > Object > Home > Object > Body > Object > Home > Object > Body > Object > Home >

For many of us queers, homes are often defined by their fleeting-ness. They are never permanent. There is a continuous seeking of home elsewhere, migrating from ‘familial homes’ in search of spaces that might welcome us.

Friends are made in new cities and they fill newfound homes with objects. These objects carry meanings, and in time, new meanings are also given to them.

The performance ‘Let’s Make a Home’ was conceived on similar lines. In its two iterations, it has been performed both intimately and publicly. The first took place at a home as part of my birthday get-together. Friends were invited to bring an object that reminded them of home but was something they were ready to let go of. During the soirée, the guests gathered together and were asked to present the object they brought. Everyone adhered to the invitation’s instructions. The second iteration occurred as part of a performing arts festival, where participants knew the details beforehand.

The space was filled with diverse objects: a small old phone, a childhood photograph, a book, a vessel, a packet of masalas, a box of rice, a cube of cheese, a packet of instant noodles, an old painting, a bottle of analgesic, dried flowers and leaves, a hand-drawn card, and an old one-rupee note.

After everyone had placed their objects on the empty table, they were asked to choose one that was not theirs.

Holding the object of a fellow guest, each person shared how it reminded them of home. The narratives built through the nostalgia of home started filling the space. These objects, part of a slice of memory, made up home for the folks present — objects whose presence is felt even in the absence of their past life. The space became one of intersecting histories of the participants/guests. The narratives linked to the object implicitly elaborated on one’s social location.

The interaction of the object in the past is given a new meaning by the new user. The memory of it remains, while a new memory forms around it. This exchange, heightened by co-presence and shared memories, not only brings different contexts together but also transforms individual memories into shared ones. The object in the performance has an afterlife of its own after the ephemeral exchange. José Esteban Muñoz who was a Cuban American academic in the fields of performance studies as well as queer theory employs ephemera as alternate modes of textuality and narrativity like memory and performance. He is interested in looking at the traces left after the performance, the “traces, glimmers, residues and specks of things” [1].

The residue of a performance may often convey more than the performance itself.

As the participants collected their thoughts and listened to each other, the evening brought with it a palpable sense of togetherness, even if ephemeral, the act of sharing engendering a shared sense of belongingness.

The performance action ‘Let’s Make a Home’ seeks to highlight a move beyond heteronormative inheritances and engages with queer modes of sharing and making homes.

Many at the get-together were meeting each other for the first time. An action built on the exchange of objects can lead to the possibility of solidarities of some kind. For someone who is always changing homes, moving to new cities, towards new futures, objects can often make a place feel like home. These objects could be material or immaterial but are necessary elements for the meaning-making of homes. These objects may also be looked at as choses en mouvement (“agents”)[2]. In a queer imagination, objects are often difficult to describe in terms of their culture and social contexts because of their moving and transitory nature. A connection can be made through intentions as a liaison between objects and context. Since objects are not in isolation, they are often in conjunction with other objects and often in a whole space.[3] The objects gathered through the performance hold different meanings for each person present, but their conjunctions with other objects framed through the idea of home open a possibility of meaning-making and different provocations.

The performance explores the production of performative space which is both personal and communal allowing a possibility of juxtaposing diverse histories and social positions. However, the act of curating such a space raises important questions: Who feels comfortable enough to share? Who is present, and who is missing?

In the initial iteration of the performance, it was set within the intimate confines of the artist’s home. This setting could naturally bring in a sense of closeness and familiarity among participants, who were primarily friends and acquaintances. The domestic environment, a private and personal space, encouraged an openness that might not be as easily achieved in a more public setting. Here, the act of sharing objects imbued with personal significance was supported by the comfort of being among known individuals, within a space that was already charged with personal memories and meanings. However, this also raises important questions about who is invited into such a personal space and who remains excluded. The decision to hold the performance at home inherently involved choices about inclusion and exclusion, as the guest list was necessarily limited by the physical space and the personal nature of the gathering.

When the performance was later translated to a public festival space, the dynamics shifted. Festivals, by their nature, are designed to attract broader audiences, offering a platform for diverse artistic expressions. However, they also bring with them new layers of complexity, particularly around the concepts of public and private. The festival setting—a more public, structured environment—invited a wider audience to engage with the performance. Yet, this broader access came with its own set of challenges. Festivals are often ticketed events, and this barrier can be exclusionary, limiting participation to those who can afford entry or are aware of such cultural events. The transition from a private home to a ticketed festival space introduces the potential for exclusion such as socio-economic factors, making the performance accessible to some while potentially excluding others.

The performance, in both settings, invites reflection on the filters—such as cultural background, social class, and familiarity with performance art—that determine who feels welcomed or able to participate. The performance sets out to explore the creation of a communal home but at the same time also challenges participants and observers to consider how the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion are drawn within any community, even in spaces imagined to be open and welcoming.

The site became a place to look at objects as a part of home-making practice. As Blunt and Dowling underline, these practices become a medium by which dwellers ground personal and social meanings in the new residence, turning it from a house into their home.[4] It became a space where objects might not be prized for their market value but for the associations, affective, and emotional geographies they produce. As Stiles traces, the importance of such objects lies in containing traces of the history of past action (life) through the present and with a view to the future.[5] This performative space highlights the overlapping and collaborative project that may be a ‘queer home’ one gets to take part in it and take someone else’s home to their home. This idea, in some ways, could facilitate newer modes of queer world making through sharing one’s homes, giving them further mobility, and presenting what it means for queer folks to make a place home in worlds that are least welcoming and heteronormatively coded.

An ephemeral space becomes conducive to sharing through friendship and intimacies towards a world desired. To not just think of what and how queer homes are made but what queering of homes entails—a tapestry of possibilities of finding homes.

Home is performatively polyvalent. The ‘doing’ of home is like a performance. In its repetitions, there will be mutations. There will be traces and impressions of it left. It is in the here and now as much as it is in the memory of it.

References

Appadurai, Arjun. 2013. The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arcidiacono, Francesco, and Clotilde Pontecorvo. 2019. Home Spaces and Social Practices.

Blunt, Alison, and Robyn Dowling. 2006. Home. New York: Routledge.

Muñoz, José Esteban. 1996. “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts.

Stiles, Kristine. 2012. Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Notes

[1] José Esteban Muñoz, “Ephemera as Evidence: Introductory Notes to Queer Acts,” Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 8, no. 2 (1996): 5-16, 10.

[2] Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 17.

[3] Francesco Arcidiacono and Clotilde Pontecorvo, Home Spaces and Social Practices (2019).

[4] Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling, Home (London: Routledge, 2006).

[5] Kristine Stiles, Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

About the Author

Manvendra is an artist with an expansive background and keen interest in Performance Studies. Their work explores the intersections of performance, identity, and social inquiry, with a particular emphasis on the concepts of home and belonging. Passionate about digital and everyday performances, Manvendra creates both virtual and real time performance art pieces that serve as platforms for imagining an alternative. Deeply inspired by the vibrant landscape of Delhi, which they consider their first love, Manvendra’s work is driven by an enduring curiosity about the transformative potential of performance art.

Beyond Flesh: An Interplay between the Internal and External Narratives of the Body in Performance Art

AUTHOR

Tejaswini Loundo

“We are the material, our bodies and minds the medium of our exploration. The research is experiential as is the material.”[1]

I – First Words

The human body is a landscape made of our various experiences, like a living, breathing, expressing canvas. The physical form (deha) is home to the spiritual form (ātman). Indian philosophy views the body as a miniature version of the universe itself: a microcosm where our physical and metaphysical existences profoundly entwine. The body is the medium through which we experience the world and the instrument through which we perceive, think, act and reflect. Through its physical processes and expressions that shape one’s external narratives, the body conveys the multitude of one’s inner processes – the emotions, thoughts, and experiences that shape one’s internal narratives.

Let’s take for instance, the reader. At this very moment, the reader is focused on reading the sentences. The eyes follow from word to sentence, sentence to paragraph; maybe every now and then his/her face expresses doubt, surprise or curiosity; or the fingers may be fidgeting as a natural response to his/her state of concentration. Alongside reading the sentences, the reader is concomitantly aware of what the sentences connote, as he/she engages in the cognitive process of ‘making sense’, using their opinions and experiences as raw material.

J. H. Gill states: “Human existence is characterized by a unique amalgamation of conceptual, or symbolic, activity and physical embodiment. We are at once both mind and body, even though in some contexts we may seem to participate more fully in one or the other. We attend either from our bodies through our minds to the world, or from bodies directly to the world”.[2]

This interplay between the individual’s internal and external becomes especially relevant and evident in the realm of performance art, and especially in movement.[3] Accordingly, the body is both the medium and the site for the interplay between various narratives.

II – The Body’s External Narratives

The body does not merely house various narratives. At the most fundamental level, the physical, visible form of the body tells stories holding traces of our ancestral, personal, and social constructions. The ancestral constructions (sanskāras) are those that have been inherently passed down through generations, such as our physical features, skin colour, and mannerisms. The personal constructs make up an individual’s convictions and lived experiences, expressed through body language – the postures, gestures, gaze, makeup, clothing, adornments, and so on. The body also reflects the social-political constructs that define our cultural landscapes through spoken language, dress codes, education, etc. In essence, the body serves as a living museum that bears the traces of all that we have lived, all that we have inherited, and all that we belong to. Consequently, such constructs suggest narratives that are inseparable from any body, and moreover from a body that performs in art. Here, such physical narratives are methodically studied and executed as techniques that put in place a process of training the body so as to enable it to express appropriately and artistically.

According to the Indian aesthetic tradition of the Nātyasāstra, we may understand the external narratives of the physical body (deha) in terms of the following key elements: (i) āngika abhinaya (physical expression); (ii) vācika abhinaya (verbal expression); (iii) āhārya abhinaya (visual presentation).[4]

III – One’s Internal Narratives

Beyond the physical, the artist’s body is also rich in its internal narratives – emotions, beliefs, experiences, feelings, and values that lie at the core of one’s being. These internal narratives are inherently dynamic and ever-changing, mirroring life itself. Consequently, these deeply personal narratives are intrinsic to any work of art, as art and the artists are inextricably intertwined. And yet, while performing their art, the performer goes much beyond the confines of their own narratives, portraying characters with experiences that may differ from their reality. If so, how can an artist interpret the Other?

The Nātyashāstra postulates that human emotions (bhāva) are fundamentally universal, i.e., they belong to all people irrespective of their culture and/or faith. These bhāva or emotional states, such as love, anger, fear, compassion, and wonder, are considered to be the building blocks of human experience. As such, for a performing artist it is key to methodically study the sātvik abhinaya, i.e., the practice of embodying the essential universality of emotional states. In fact, a deeper understanding of the universality of human emotions enables the artist to delve into the depths of their ātman (soul) and realize within the depths of his/her own personal experiences, the connecting dots and links that bind him/her to all other beings. This interplay of their various internal narratives is indeed the truth of the artist.[5] By going beyond the ‘self’ and fully interpreting the character, the performance blurs the distinction between the artist and the art. Thus, “the dancer and the dance are inseparable, but neither is simply a function of the other; nor are they the same”.

IV – The Body, the Narratives, and the Audience

It’s a fact that the essence of performance art lies in the artist’s ability to transcend the boundaries of the ‘self’. For that to happen, a vital factor is the audience. Art remains incomplete as long as it does not engage the audience as an intrinsic dimension of itself. Let’s imagine a drop of water falling down into a quiet still pool. As it collides with the surface, the drop not only fully merges into the pool, but also creates a ripple that spreads out wide. This is the relation between bhāva and rasa. Bhāva, the performer’s emotional states, is the drop of water; and rasa, the shared emotional consciousness reflected in the audience, is the ripple. This agrees in toto with the etymological meaning of the Sanskrit word rasa as “juice,” “taste,” or “essence”. Accordingly, the art and aesthetic traditions rooted in the Nāṭyaśāstra study the emotional states evoked in the audience, through the consumption of art, as the rasa theory.

This collective consciousness, which gains transparency as we move from bhāva to rasa, is precisely what lends performance art its authenticity. The body is a universal language we all innately understand. Unlike the ambiguity of words, the body’s physiological expression allows it to be read, first and foremost, intuitively and viscerally, before any consequential cerebral interpretation. This is what yields its honesty. The inherent truthfulness of the body in performance empowers the artist to engage the audience, by means of their own experiences and emotions. This is further heightened by the ephemeral, fleeting nature of performance art, where each moment is a unique, unrepeatable manifestation of the artist’s physical presence. “It is, as Merce Cunningham puts it, “the art of the present tense”” (Peter Arnold, 2000).

V – Concluding Words

This capacity of performance art to resonate with the fundamental truths of the human condition, is what lends it its power and relevance.[6] These fundamental truths in a broader context, beyond the individual, are essentially reflective of social and political realities. As such, in every case, the personal is immediately social-political, and vice-versa. The body becomes the privileged site where broader issues of power, identity, politics, and human experience are explored and shared with the audience. Furthermore, placing performing bodies outside conventional artistic frameworks, such as those of non-traditional spaces (site-specific performances), challenges the dominant narratives that control those spaces. This allows questioning and alternative perspectives to emerge and expand one’s perception of space itself.

In other words, performance art harnesses the transformative power of the body which challenges and deepens our collective understanding of the world around us. Body – a repository of memories, a voice for resistance, a medium of transformation, a mirror for society – evolves dynamically prompting the world to equally evolve.

References

Arnold, P. J. 2000. “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance. Journal of Aesthetic Education”. p 87–95. <https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657> Accessed on 23/07/2024

Bharata Muni. Nāṭyaśāstra. 2014. English Translation from Sanskrit by Adya Rangacharya. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

Chadha, Monima. 2022. “Personhood in Classical Indian Philosophy”. <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2022/entries/personhood-india/>. Accessed on 23/07/2024

Cohen, Bonnie Bainbridge. 2020. “An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering®”. <An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering® – Body-Mind Centering® (bodymindcentering.com)>. Accessed on 23/07/2024

Gill, J. H. 1975. “On Knowing the Dancer from the Dance. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism” p 125–135. <https://doi.org/10.2307/430069> Accessed on 23/07/2024

Green, Jill. 2002. “Somatic Knowledge: Green, Jill. (2002). Somatic Knowledge: The Body as Content and Methodology in Dance Education. Journal of Dance Education. 2.” <https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2002.10387219>

Ramaswamy, A. and Deslauriers, D. 2014. “Dancer – Dance – Spirituality: A phenomenological exploration of Bharatha Natyam and Contact Improvisation’, Dance, Movement & Spiritualities”. Intellect Ltd Article. English language. p. 105-122 <https://doi.org/10.1386/dmas.1.1.105_1>.

Schiphorst, Thecla. 2009. “The Varieties of User Experience Bridging Embodied Methodologies from Somatics and Performance to Human Computer Interaction; Ch 2: Embodiment in Somatics and Performance.”. Unpublished thesis manuscript, University of Plymouth.

Vatsyayan, Kapila. 1968. Classical Indian Dance in Literature and The Arts. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi.

Watave, K. N., & Watawe, K. N. 1942. “THE PSYCHOLOGY OF THE RASA-THEORY. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute”. 23(1/4). p 669–677. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/44002605>

Notes

[1] See Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, An Introduction to Body-Mind Centering® (2020).

[2] J. H. Gill, “On Knowing the Dancer from the Dance,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 34, no. 2 (1975): 125–135, https://doi.org/10.2307/430069 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[3] “The dancer is dependent upon the articulation of her own bodily form in such a way that it conveys aesthetically what is intended,[…] the moving bodily form of the dancer is in a very real sense the basis of the dance.” P. J. Arnold, “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 34, no. 3 (2000): 87–95, https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[4] In Indian Aesthetics, abhinaya means the art of expression, i.e., in essence, the art of performance. In Sanskrit, abhi means ‘towards’ and nii means ‘to lead/guide’. In other words, it could be literally translated as “leading (an audience) towards”.

āngika abhinaya (physical expression), comprises the body’s movements, gestures, and postures; here, the study of the technique is of utmost importance; vācika abhinaya (verbal expression), comprises the use of language, including speech, chants, music, and vocalization; āhārya abhinaya (visual presentation), comprises the visual aesthetics of the body, including costume, makeup, adornments, and also scenography.

[5]“[…] as S. J. Cohen points out, that “the audience comes to the dance through the agency of a personality (the performer) who, no matter how hard he may try to be a merely colourless vessel through which the genius of the author is transmitted, somehow transmits a part of himself as well. Furthermore, the more closely he approaches the condition of the colourless vessel, the less interesting the dancer becomes as a performer.”” See P. J. Arnold, “Aspects of the Dancer’s Role in the Art of Dance,” Journal of Aesthetic Education 34, no. 3 (2000): 87–95, https://doi.org/10.2307/3333657 (accessed July 23, 2024).

[6] Irrespective of whose body we refer to, the performer or the audience, “bodily experience is not neutral or value free; it is shaped by our backgrounds, experiences and socio-cultural habits. […], our bodies are constructed and habituated.” See Jill Green, “Somatic Knowledge: The Body as Content and Methodology in Dance Education,” Journal of Dance Education 2, no. 4 (2002): 114–118, https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2002.10387219.

About the Author

Tejaswini Loundo is a movement art practitioner from Goa, India. As an artist, she is interested in an interdisciplinary approach and intercultural dialogues. Her work explores the intersection of Indian and western contemporary themes and movement arts through an experimental lens. In addition to her dance practice, she is also a creative dance teacher and an aspiring writer. She is trained in Kathak (an Indian classical dance) and western contemporary dance techniques. She holds a BA in English Literature and two professional diplomas in dance: one in Indian Movement Arts and Mixed Media (Attakkalari Centre for Movement Arts, India) and one in Western Contemporary Dance (DanceHaus Accademia Susanna Beltrami, Italy). Tejaswini believes art creates a space where the artist and audience can cohesively unify in a shared experience; our existential oneness.

Counter-Mythologies in Mandeep Raikhy’s Hallucinations of an Artifact

AUTHOR

Gauri Yadav and Rayan Chakrabarti

Hallucinations of an Artifact [1] is a 50-minute-long performance work by choreographer-dancer Mandeep Raikhy which resuscitates the figure of the ‘Dancing Girl’ of Mohenjo-daro. On stage we see this possibility being enacted and probed by three dancers—Akanksha, Manju, and Meghna—performing around three small pedestals. This work is an important inquiry into popular imagination—what are the qualities associated with the body of a dancer and how have these been formulated through colonial nomenclatures and post-colonial ideas of Classical Indian dance forms? Raikhy is also engaging here with the contentious politics—of gender and culture—converging upon a heritage artefact like the Dancing Girl.

In Hallucinations, there are several bodies to account for—the audience’s memory of the bronze figure from Mohenjo-daro, the three performers, and the indefinite number of figures in the AI projection. The performers replicate the stiffness of a bronze figure to enact what the artefact would look like if it came to life. The posture of the Dancing Girl with the hand on her hip with the left step slightly forward, is the basis for most of the movement in the performance.

But they are constantly breaking out of this pose by inverting their arms, by raising their fists in the air or arranging their bodies in a plank or in the downward dog position, a yogasana. Through interventions like these, the performers create not replicas but afterlives of the figurine by negating its popular imagination as a dancer alone and pushing the limits of what could be typified as ‘dance’. The movements are a jarring collection of everyday postures, popular dance steps, and yoga poses stitched together by frenetic runs along the length of the stage.

Close-up footage of the figures’ body parts is played as the performers in the foreground enact play, conflict, sex, and rest. The performers seem like predators out preying as they scream, push, and run from and towards each other. In one scene, the three performers embody a spirit of playfulness, as they strut about trying to intimidate the others. Two of them corner the third when she suddenly pushes out with her fist on the shoulder and the elbow sticking out like a gun. This section comes to an end as one of the performers runs off and begins rapid hip and arm movements standing next to the wall. Against settled meanings, this artefact offers the power of the erotic. It is this state of the transformation of chaos into eros that Audre Lorde explains in Sister Outsider:

The very word erotic comes from the Greek word eros, the personification of love in all its aspects— born of Chaos, and personifying creative power and harmony. When I speak of the erotic, then, I speak of it as an assertion of the lifeforce of women; of that creative energy empowered, the knowledge and use of which we are now reclaiming in our language, our history, our dancing, our loving, our work, our lives.[2]

The information brochure handed out before the performance at Black Box Okhla, calls it a ‘playful and notoriously unclassifiable artifact’. This ‘play’ becomes a means of empowering an alternate understanding of what the artefact could possibly be about. In the performance, the figure comes to life with a brashness and swagger which is uncharacteristic of its memory as a graceful and petite ‘dancing girl’. When the artefact was excavated in 1926, British archaeologists[3] named it on the basis of colonial perceptions of Indian Classical dance. Raikhy uses movement vocabularies to decolonise the ‘dancing’ figure itself. Would this iteration of the Dancing Girl be classified as a dancer?

The questions of classification bleed into the perceptions of the audience. The performance’s interaction with the public is two-fold. Firstly, the performing body exceeds the demarcated space of the arena. In one instance, the dancer falls into the lap of someone in the audience. Another time, the performer sustains eye contact while making a powerful hissing sound. Secondly, Raikhy’s oeuvre points to his constant engagement with public discourse, whether through short performance pieces like Secular India staged in JNU in February 2023 or Queen Sized, a work which critiques Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code and is staged in a room with a charpai.

The hallucinations in this performance annihilate desire to the point where the idealised codification of Indian Classical dance breaks into free-form to create a specific mode of denial. Firstly, a firm critique of colonial visions of archaeology and the exoticisiation of Indian artefacts seems prominent. This is centred on challenging the public memory of the Harappan Civilisation and, by extension, the usage of its artefacts including the ‘Bull’ and the ‘Proto-Shiva’ as representations of a glorious Indic or Hindu culture. Secondly, the performing body refuses to conform to the logic of the Partition. Even as India retained this artefact and Pakistan inherited the Priest-King, the consistent disregard of the pedestals throughout the performance emerges as a rejection of processes of museumisation in postcolonial nation-states. This is evidenced by another dancing body unveiled at the Museum Expo in Delhi. The attempt to encode the Dancing Girl into the heritage politics of ‘Bharat’ is a classic case of how majoritarian narratives clothe naked truths. In addition, there is a definite choice of a body type and skin colour, which is rebuked by the performing body choreographed by Raikhy.

It is the contrapuntal energies of annihilation and reconstruction that the AI body too seeks to explore. Collaborator and technology artist Jonathan O’Hear imagined the generative movements of the artefact on screen and expanded it into a short film. The ‘coming to life’ movements can be juxtaposed with those in Dai[4], an artistic experiment where O’Hear trained an AI robot to learn about art. In Hallucinations, he explores through a non-humanoid dancing body the radical futures of contemporary dance. Here lie the glimpses of the cyborg body—the ultimate fusion of person and machine. This interaction sets up large sequences in Raikhy’s choreography. The AI body undergoes radical fractures by spatially dangling the Dancing Girl in unfamiliar scapes—the ruins of a monument, the quotidian vistas of a busy city. It is a return to the power of the everyday that underlines these juxtapositions. O’Hear imagines the Glitching Girl partying as a teenager as well as going sightseeing to the Indus Valley, occupying everything and everywhere.[5]

Is it possible to find linkages in these hybrid bodies with Antonin Artaud’s Body without Organs?

In a radio play, Artaud wrote,

When you will have made him a body without organs,

then you will have delivered him from all his automatic

reactions

and restored him to his true freedom.

Then you will teach him again to dance wrong side out

as in the frenzy of dance halls

and this wrong side out will be his real place.

– Antonin Artaud, To Have Done With the Judgement of God (1947)[6]

The Body Without Organs is often said to be an ‘intense egg defined by axes and vectors, gradients and thresholds, by dynamic tendencies involving energy transformation and kinematic movements involving group displacement, by migrations: all independent of accessory forms because the organs appear to function here only as pure intensities.’[7] Similar migrations displace the artefact and dancers within the performance space, defined by short sprints. There almost seems to be a transfer of energy as the performers willingly glance upon and build on the moving image of the Dancing Girl, even leaning against the projection wall to create an illusion of reaching out, the semblance of harmony.

The issue of solidarity informs another work by Raikhy which premiered at the OddBird theatre in Delhi : Anatomy of Belief (2019), where four performers used gestures of worship to explore if there is an essential humanness in the act of prayer. The four gestures, including bowing, kneeling, palms pressing together, and bringing the forehead to the floor, were repeated at varied paces and broken down to show what prayer physically comprises.[8] The two works share a similarity in the way gestures are interpreted by bodies themselves. In the atmosphere of communal politics and violence, the audience was forced to confront the implication of their daily rituals. In Hallucinations we find the artefact playing with the limits of its static gesture and stiff limbs. The repetition of its movement (on screen and on stage) creates an atmosphere of shock when the audience is thrown off its complacency by the incoherent screams of the performers, beats of the soundtrack, and the disjointed movements of the bodies. It interrogates the audience’s ideology and perception along the lines of gender in dance and the overlapping terrains of history and mythology. In an interview,[9] Raikhy explains the role and nature of the audience during provoking performances like Queen Sized. Performing a work like that in front of audiences who are already abreast with its nature and comfortable with its progressiveness is redundant. Raikhy seeks instead to take his work to unfamiliar audiences, to introduce the nuance of its themes so that they can partake in processes of critique, unlearning, and revision.

The power of the hallucinating body lies in its ability to form combative mythologies; glancing simultaneously towards the past and future. Efforts to revise myths have been the subject of a plethora of performative as well as literary works. Sahej Rahal, for instance, focuses on bringing mythical creatures into the domain of liminal rituals. In Tandav III, he uses the sci-fi element of the lightsaber to create hybrid archetypes. Revisionist work is an important intervention when dealing with elements from the past, whether these are histories of violence or the violence of the archive in classifying artefacts like the Dancing Girl. The body becomes that plane of potentiality and the process of becoming that leads us into deconstructions, constantly remoulding both human and non-human terrains.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jk6w.

Betsky, Aaron. 1997. Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire. First edition. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2003. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (Series Q).

Mayer, Sophie. 2015. “Uncommon Sensuality: New Queer Feminist Film/Theory.” In Feminisms, edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers, 86–96. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press (Diversity, Difference and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures).

Mbembe, Achille. 2002. “The Power of the Archive and its Limits.” In Refiguring the Archive, edited by Carolyn Hamilton et al., 19–27. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2002. Phenomenology of Perception. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994610.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 1993. Tendencies. Durham: Duke University Press.

Notes

[1] https://prohelvetia.ch/en/whats-on/from-silences-to-power-co-creation-projects-from-switzerland-and-south-asia/

[2]Popova, Maria. 2023. “Uses of the Erotic: Audre Lorde on the Relationship Between Eros, Creativity, and Power.” The Marginalian. August 18, 2023. https://www.themarginalian.org/2023/08/18/uses-of-the-erotic-audre-lorde/.

[3] Ghose, Anindita. 2017. “What if the ‘Dancing Girl’ Was Actually a Warrior?” Mint Lounge, November 17, 2017. https://lifestyle.livemint.com/news/talking-point/what-if-the-dancing-girl-was-actually-a-warrior-111646919791103.html.

[4]Jonathan O’Hear. 2022. “Dai | Jonathan O’Hear.” Jonathan O’Hear | Jonathan O’Hear Artist. May 15, 2022. https://www.jonathan.ohear.com/work/dai/.

[5] Watch here: https://libre.video/videos/watch/17372c22-920c-408d-9b73-c860a17e0b4f

[6] See also: “Artaud: To Have Done With the Judgement of God.” n.d. https://surrealism-plays.com/Artaud.html.

[7] Excerpt from Rives Grandes’ curatorial note: https://www.ochiprojects.com/portfolio_page/body-without-organs/#_edn3

[8] Read more: https://mandeepraikhy.wordpress.com/anatomyofbelief/

[9] “Deconstructing Intimacy in Conversation With Mandeep Raikhy.” n.d. Ligament.In. https://ligament.in/volume2/interview-mandeep-raikhy.html.

About the Author

Gauri Yadav is a poet based in New Delhi. Trained in literature, she is now studying creative writing at Ambedkar University. She is interested in cultivating an interdisciplinary arts practice using visual, textual and performative mediums. Her work has appeared in Muse India, PARI Library, gulmohur quarterly and Monograph magazine.

Rayan Chakrabarti is a writer and academic working at the intersection of body, memory, and the nation. He is pursuing a postgraduate degree from the School of Arts and Aesthetics, at Jawaharlal Nehru University. His poems have been published or are forthcoming in Mascara Literary Review, Mulberry Literary and WritingWomen.

Phantasmic 'Queerscapes': Performing Spatialities in Debashish Paul’s Body as a Landscape; Body in a Landscape

AUTHOR

Tony Jacob

Amidst a neglected panorama oblivious to the customs and travesties of domesticity, a desolate figure treads a barren terrain. Overhead, an imminent cloud of fog hangs, within arm’s reach, threatening to engulf the actors. Flanked by a waterbody, the scenery, despite its desolation, is animated by windswept vegetation and impassioned bird-song, evoking a terrestrial tango. This is Jārgo, an arid location about thirty miles from Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, in northern India. For forty-five days, the figure serenades the landscape, traversing this expansive setting. Through this performance, the figure—barefoot, adorned with a stiff sculptural costume, a veiled headdress, and a wooden staff from which paper sculptures of houses hang, drumming against each other and the wind—contemplates their corporeal memories in relation to the untamed earth. They walk, stop, rest, perform ritualistic gesticulations, and scale the land through their treading. They collect objects and materials and draw references of local terrestrials onto their sculptural dress, evoking mountains, rivers, flowers, grass, and vegetation. This is Debashish Paul’s durational performance piece, Body as a Landscape; Body in a Landscape (2022)—a poetic reimagination of queerness. This practice (con)fabulates a limitless existence beyond the confines of the normative body, embracing a queer practice that confronts the invisibility of marginalised identities. It envisions a spatial redemption for gendered, sexualised, racialised, and othered bodies existing beyond the hegemonic socio-political realities of postcolonial India.

The figure’s transitory journey across the wretched landscape mirrors the condition of queer (in)visibility and the dejected search for spatial belonging—a struggle endemic to non-heterosexual bodies attempting to traverse the public spheres of contemporary India. In a phantasmic attempt at spatial reclamation, Paul foregrounds their corporeal bearing, to respond and react to the terrain and atmospheric conditions of Jārgo. Through their inhabitation of and interaction with the space––tending to local vegetation, adding items to their dress, and collecting objects, the figure and their space lay impressions on each other, carving out spatialities of bountiful and boundless queer acceptance, compassion, and tolerance. This centrality of the body through which Paul maps spatial formations echoes Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological consideration that affirms: “spatial forms or distance are not relations between divergent points in objective space as they are relations between these points and a central perspective—our body”.[1] Sara Ahmed’s observation that landscapes leave textural ‘impressions’ on the affective body through air, smell, and sounds extends this consideration of the body’s phenomenology towards a reciprocal body-space coalescence. The emphasis is that spaces are not external to bodies but are “second skin that unfolds in the folds of the body”[2]. In the context of queer spatiality, sexuality determines spatial formation and is determined by ways of inhabiting space—a consideration which implies that queer bodies make and are made by their spaces.[3] This illustrates the integral nature of the landscape in Debashish Paul’s performance, showing how the queer body performs inhabitation: both of and by its spatialities.

In this fabulation of queer spaces, Paul’s performance draws upon corporeal recitations––by allowing the figure to dance, walk, breathe, and exist with(in) the landscape without the fear of obliteration. This movement within the brown-green terrain of the local landscape rebuffs the invisibilities brought on by the camouflage of normativity. By resisting bodily dissolution against the soft contours of Jārgo, Paul’s movement resurrects the queer body from static oblivion, thumping a temporal rhythm that enlivens a queer sensorial continuum. The necessity of ‘movement’ as integral to queer wellbeing can be gleaned from Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s approach to queerness as a “continuing moment, movement, motive” that is “recurrent, eddying, and troublant”; as an existence “across” genders, sexualities, genres, and “perversions”.[4] This synonymisation of ‘across’ as a mode of ‘queer movement’ within the context of Paul’s performance hints at a certain aesthesis of traversing and transposition—a modal fluxus of self-fashioning that proposes undulating shape-shifting landscapes as tropes for queer visualisation. This landscape, or ‘queerscape’, emblematic of queer memories, experiences, feelings, and sensations, is posited as a ‘contingent and tangential’ space that repurposes ‘public space’ to ‘disrupt what heterocentric ideology assumes to be an intimate, coherent relation between biological sex, gender, and sexual desire’[5]. The evocative quality of Paul’s ‘queerscape’, critiques the intolerance of public spaces, reckoning with the violence of heteronormativity, while gesturing towards nonviolent interstices for queer self-proclamation, declarations, and visibilities.

The implications of using queer fantasy to create convalescent, phantasmic queer spatialities within public spaces lie in its scope to re-create non-normative histories from absences or non-visibilities. This imagination, as seen in Debashish Paul’s performance practice that relies on the fantastical or magical, necessitates archival operations that demand creative and critical approaches to access. This non-bureaucratic archival conceptualisation rallies the intimate, the personal, and the emotional as powerful inventorial forces that promulgate queer visibilities. Establishing such an ‘archive of feeling’ calls for affective interventions that necessitate transposition, absorption, and effective engagement with non-normative sensations and solidarities.[6] This interaction with the queer archive, collected from the quotidian, calls for a queering of the senses or a deliberate de-centring of the visual phenomenon of anteriority: the archive leaves ‘impressions’ through air, smell, and sound. This ‘queerscape’ enacts the ‘materiality’ of the queer archive, becoming a moment where embodied sensorialities of queer bodies come together to make a collective public reformation.[7] Through their redemption of queer histories, which struggle to be recollected within the mechanisms of our collective postcolonial condition, the artist’s performance reminds us of the phantasmagoric potential to conjure magical ‘queerscapes’ within the recesses and hollows of our limitless bodies.

Except from Body as a Landscape; Body in a Landscape, 2022. Video Credit: Saurabh Singh.

References

Ahmed, Sara. 2006. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jk6w.

Betsky, Aaron. 1997. Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire. First edition. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2003. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (Series Q).

Mayer, Sophie. 2015. “Uncommon Sensuality: New Queer Feminist Film/Theory.” In Feminisms, edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers, 86–96. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press (Diversity, Difference and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures).

Mbembe, Achille. 2002. “The Power of the Archive and its Limits.” In Refiguring the Archive, edited by Carolyn Hamilton et al., 19–27. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2002. Phenomenology of Perception. 2nd ed. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994610.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. 1993. Tendencies. Durham: Duke University Press.

Notes

[1] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 2nd ed (London: Routledge, 2002), 5. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994610

[2] Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 0. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jk6w.

[3] Aaron Betsky, Queer Space: Architecture and Same-Sex Desire (New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1997), 67.

[4] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993).

[5] Sophie Mayer, “Uncommon Sensuality: New Queer Feminist Film/Theory,” in Feminisms, ed. Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2015), 86–96.

[6] Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003).

[7] Achille Mbembe, “The Power of the Archive and Its Limits,” in Refiguring the Archive, ed. Carolyn Hamilton et al. (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2002), 19–27.

About the Author

Tony Jacob is a writer, researcher, and creative practitioner from Kerala, India. His research interests include politics of censorship, (non-)erasure as epistemic and aesthetic practice, representations of spatialities, and poetics of care within modern art and contemporary artistic practices. He holds an MA in Contemporary Art Practice from the Royal College of Art, London, and is the founder and organiser of an interdisciplinary artistic research forum Critical Symposium.

The Body Chronicles: Tales of Horror and Hearth

AUTHOR

Shreya Bhowmik

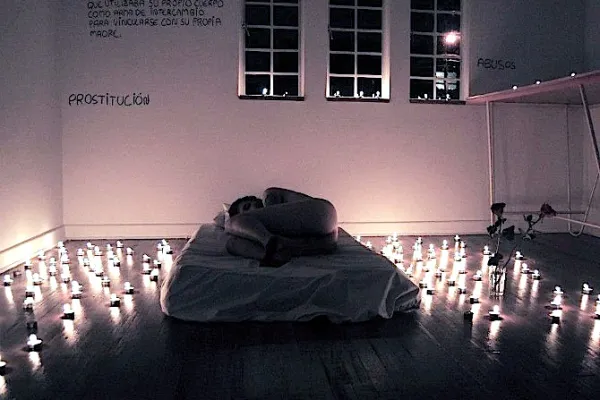

“I was born from the purchase of my mother’s body, and the sale of mine makes my skin feel like it did that night.”

In the beginning of Empathy and Prostitution, we see a visitor placing money and turning into an active participant, thereby establishing a bond between themselves and the artist lying naked on the bed. Actions change with people; some act on their sexual desires while others hug Abel longingly. Either way, the body channels the unspeakable. This is the premise that brings Abel Azcona closest to his mother. His life has been marked from the very beginning with the transactional impermanence of a neoliberal regime. Corporeally, Abel lies completely vulnerable in the room located in the gallery, accessible and at the mercy of the many visitors, spectators, and eventual performers. He appears fragile, curled in a foetal position in between white sheets. For one hundred Colombian pesos, his body becomes another’s property for three minutes. Reading the reactions means swinging between violence and affection; he is spanked, whipped, hugged, and caressed. As he gives his body over to the viewer and turns into another element of the performance, re-enacting the transaction that resulted in his accidental birth, he is also in many ways turning the tables and bringing the viewer into his world, seeking empathy for not just his mother but for the audience themselves whose reasons for participating are myriad but not central to the narrative. Azcona, aware that his life is a ‘mistake’, invites others into a realm of understanding where mistakes, though unnecessary, can still forge a bond, perhaps with an absent mother whose memories he now carries in him like in a womb; the roles are reversed. The atmosphere is thick with tension, the flickering light producing a semi-darkness as the smell of sex permeates the air. But there are fleeting moments of joy when he jumps on the bed with crazy abandon. It’s as close to home as Abel can get.

The body is the vector and the resource Azcona has at his disposal to reveal the cruelties of man-made structures of power and desire. His birth, from the union between his heroin-addict prostitute mother and an unknown father, was the result of a nexus of exploitative forces. His mother was not allowed to abort, his childhood was spent in poverty, mired in physical abuse and social stigma. Adopted by a wealthy family at the age of 7 that was ultra-religious, he grew up on the principle of corporal punishment, and his life was marked by intermittent violence until he ran away and began living on the streets. While in a psychiatric hospital and diagnosed with a personality disorder, he heard of performance art and has since been making participatory performances and installations. His works, often radical, comment upon instances of abuse, oppression, and fascism, and are committed towards expanding the dialogue around taboo subjects.

Drawing upon the context of his birth, in Biological Meetings, Abel is seen lying in the foetal position under a white sheet held by a heavily pregnant woman. When he was 26, he shaved his legs, pumped hormones in his body to develop breasts, and prostituted himself in the Santa Fe neighbourhood of Bogotá; he called this work La Calle (The Streets). In La Guerra (The War), he serves up his ketamine-induced body at the altar of people’s imagination; he is simultaneously in the performance and not there. In this work, he enters a trance-like state, inviting both pleasure (some caress him) and transgression (others put out their cigarettes on his body). With his face pushed against the pillows, he gives the impression of not being wholly unconscious, thus signifying a limited presence but a presence nonetheless. Through all of these, Abel wants to reach the moment of his conception, perhaps to confront a world that thrives on hyperconsumerism but limits choices – his art seems to be an attempt to show the rot in the system that dehumanises people like Azcona’s mother and prevents them from exercising their rights to a dignified life. In his exhibition Political (dis)order in Romainmôtier, (t)his body disappears from sight: all that is present are some documents he procured—party memberships, donations made to parties in Spain and in other countries, letters of thanks for donations, receipts, etc. A person, in effect, is reduced to a number or a card. This work came at a time when Spain was mired in crisis; rampant corruption, a weakened opposition, and the whole system thrown into disarray. In Pain, a project in collaboration with Lili Txt, he drags himself around with a noose tied around his neck: an umbilical cord, once an anchor, now a cross to bear. Through interventions like this, the artist demands accountability from those who claim to serve people; he demands an answer for his mother and her memory.

Azcona first performed at the age of 16: he sat naked on a chair and screamed in the middle of a road in Pamplona. He stopped the traffic. Since then, his artistic process has pushed him into the relentless pursuit of understanding his past. Enacting an investigation that is autobiographical in nature, his works deal with gestation, bonding, motherhood, abandonment, and discrimination. The body is his chosen tool of resistance and catharsis; a space of confrontation and encounter with his personal demons and our collective horror. This body is the only space he has shared with his mother; his works are, therefore, intimate and private. He shares his rootlessness with those who dare to cross the line and move into the realm of the humane. I access this through a video recording of the performance, the corporeality rendered inaccessible by distance, time, and space. His body remains out of touch but the gestures are loaded with meaning; his act is one of seeking company in a fleeting moment of vulnerability. It feels like he is choosing again and again to be born, to be abandoned, to suffer abuse, and to return to a time when all of this did not exist, when he did not exist.