BIRDS OF HUNGER Part 1

When Devi Devasi first saw the plane that brought supplies during a great spell of hunger, she was afraid that it would come shuttling down on her small head. She recounted the day to me on a warm July afternoon in her village, and drew an accurate silhouette of a plane with a stick on the mud floor where we sat. “It was so big, have you seen one up close? And we were so hungry. Hunger makes a man smaller than he already is”, she said. Devi’s village is outside Jodhpur, one of the largest cities in Rajasthan, and is part of what comprises the erstwhile kingdom of Marwar. Devi is in her late 60s and one of three siblings who were raised without a mother. In 1970, when the plane visited, she was barely ten years old. Like many with the same last name, Devi is a member of the Rebari community. Rebari – also referred to as Raikas – are traditional nomadic-pastoralists that herd camels, sheep or goats, and move across Rajasthan and other parts of India’s Northwest through the year.[1] The famine caused by the drought killed all edible food, but also fodder for the animals. “So, even if we were fed, our animals were not. Even today, if they don’t eat, it feels like we have not eaten. Without them, what purpose do we have?” Devi said.

The drought and famine of 1969-70 was one of the more severe in Rajasthan’s recent past, and like many similar times in the past, aid did not reach hungry villagers. Families abandoned their smallest children, thousands left on foot in search of a plate of food. Devi recounted that in the 1970s, her family had little or no land to sow for food, so relying on stored grain was not possible and the only way out was to beg. “One baniya seth[2] gave us ‘moong ka paani’ – the water which dal was boiled in – to drink”, she said. They also ate tree barks, some ghee that was miraculously left over in a small jar. For water, they dug with their hands near ponds. All what was available was sterilized to maximum possibility and consumed. The government plane, though gigantic, brought little relief to the village. “Some sugar, and lots of ‘gehun’, or wheat.” Devi said. But the wheat was mostly inedible. Even so, she cooked what was available into “kaccha-pakka” or half-cooked rotis for siblings on a small fire. Since 1970, Devi remembers several other famines and droughts. She would move to another village after she was married, but scarcity persisted in her life. For most families of rural Rajasthan, and particularly those of marginalised castes, famine is knitted into the everyday, it descends with a sudden tremble in time. “Famine sticks to Marwar like flies to mawa barfis”, Devi said, turning to metaphor to lighten the weighty memories she retold.

**

While the nature of famines in Rajasthan differs between provinces and climates, the word for them, ‘Akal’, inspires similar ruefulness. Akal, pronounced ‘kaal’ means both drought and famine in local dialects, which indicates the interwoven nature of the two phenomena that define the majority of Rajasthan’s lives. Akal is of four types: Annakal, a famine of grains; Jalakal, a famine of water; Trinakal, a famine of fodder and Trikal, the most severe — a drought of all things; when food, water and animal-feed, all disappear. Akal occurs most commonly due to the lack of rainfall, or an excess of it — even today, a majority of Rajasthan’s agriculture is fed by monsoon rain. Since the 17th century, there have been various documented and undocumented famines in Rajasthan’s history — including the famine of 1698 in Marwar; and the drought of 1765 in the Rajputana —which consisted of several princely states of present day Rajasthan.

When they occurred, colonial officials and ruling royals denigrated these tragedies to peripheries, and left people unattended, their suffering unaddressed.

Before the 19th century, memories of scarcity are scattered in their mentions — there are a few surveys, and scant mentions found in travelogues of British officers, like the journal Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan by colonel James Todd. In his annals, Todd wrote about the year of 1765, and how “the ministers of religion forgot their duties. All was lost in hunger, fruit, flowers, every vegetable thing. Even trees were stripped of their bark to appease the craving of hunger. Man ate man.” By the 19th century however, hunger and starvation had increased manifold in India. “The frequency and intensity of famines surpassed those of the entire past”, notes a report published by the All India Federation of Organisation for Democratic rights in 1988 about 19th century famines.

The most devastating trikal of the 19th century occurred towards its end. This was the “Chhapanniya Akal” of 1898-1900, a famine called after the Bikrami year “Chhapan” or 2056 when it occurred. The famine was so dire that it dug through India’s Northwest, and in Rajasthan, it brought illness and hunger like never before.

By the end of the 19th century, it was clear that famines were not simply a matter of natural intervention. Even when rainfall was scarce, kings did not create irrigation channels to aid small-shareholder farmers; money-lenders from dominant-caste, trading communities like Baniyas kept desperate farmers in the crutches of escalating loans. Famines in Rajasthan were, like in other parts of the subcontinent, a result of price-rise, caste-based extortion and hierarchical, top-down neglect. The ’88 report argues this — that famines occurred due to the poverty of farmers, which was fortified through “over-assessment” by kings and the British colonial state. Rajput kings, moreover, were interested in appeasing the British rather than instating relief for their subjects, scattered through unforgiving terrains. Take that in the year 1900, priority was given in recruiting soldiers for the British army from Marwar and Mewar – an opportunity flown at by young men looking to escape hunger – rather than feeding famished citizens, or reducing widespread disease.

Of the famines in Rajasthan, records show that hunger remains a constant in marginalised castes of both Hindus and Muslims; while landowning Brahmins, Rajputs and other dominant-castes experience periodic, even if severe difficulty. For example, by the 20th century, handpumps and tube wells were dug up in villages during droughts, but these were established in the vicinity of influential and powerful groups, keeping clean drinking water out of the access for the poor. In his 1981 treatise, Poverty and Famines, economist Amartya Sen famously wrote that starvation is “not the characteristic of there not being enough food to eat, but of some people not having enough food to eat.” The paper provides a bleak and telling analysis of the Indian subcontinent’s history– which always was, and remains steeped in regularised, cyclical hunger. One look at famines in Rajasthan prove a pecking order of bodies that is not only prevalent, but the base of growing and consuming food in India even today. They are evidence that food as custom is the realm of only a few, and that even today, an agenda remains: to glorify what is eaten for comfort and cultural grandeur, simply negating the experiences and histories that do not fit.

**

In Palasani, a village close to where Devi lives, Kaburi Mirasi remembered stories of the Chhapaniya akal. Kaburi is from the community of Mirasi Muslims, who are genealogists and singers, and a historically marginalised caste in Rajasthan. Her mother told her about wild grasses that were foraged during the deadly famine, and tree barks that were scraped off to their bones to feed rummaging souls. She narrated, in particular, stories about the bark of the ‘Khejri’[3] tree, a prevalent desert species that grows across Marwar. In popular imagination, the khejri tree is associated most often with ‘ker sangri’ , a dish made with dried berries and beans from the tree, and eaten with hot bajra rotis, but for Kaburi, the tree is valuable is for its many uses during both zamana or rainfall, and famine. “Usually tree barks are harmful but the khejri ka ‘dhoda’ or bark is good for sogra and rotis.”, Kaburi said. She mentioned how ker sangri is often documented in recipe books of Rajasthani cuisine, but the tree’s bark is still left out of any mentions of sustenance or food. “The tree provides shade to a weary traveller, and each part of us is useful during akal.” Kaburi said, pointing to a tall Khejri outside her hut. “Tell me. Is there more beauty than this anywhere in the world?”.

Her daughter, Marryam, reminded her of ‘aakday ka dodiya’, or the bud of the ‘Aak’ plant. Aak grows wild in Marwar, it is a tall plant with a gummy stem; and waxy, soft flowers that vary in colour: from white to lavender. In dominant-caste Hindu communities, the flower is auspicious, used in pujas and ceremonies, but for families like Kaburi’s, it can be food at a time of need. “First you dip the aakday ka dodiya in water, soften it and eat it,” Marryam explained, as she brought out ‘kala channa’, or brown chickpeas to cook in ‘til ka tel’, or white-sesame oil that her mother makes at home. “This is my favourite” she said, beaming at the chickpeas. She picked up a fistful, and began to drop them one by one onto a small plate. Kaburi’s sister-in-law, Rukhsana Mirasi, sat down to a glass of water after she finished making a stack of rotis, slapping her niece’s palm to stop her from playing with food. “One time, we ate the kernels of the channa because there was nothing else.” She said, explaining that this this kind of provisional substitution was routine with seeds. “Everything is done to increase quantities, and make food last as long as it can.”

Kaburi and Ruksana’s family both farms and eat a local variety of Bajra. A single fist of bajra is used to make ‘rabodi’, a dish that mixes the grain with ‘khatti chhanch’ or sour curd; and also large, crisp rotis that are eaten, if possible, with ghee made with milk from their cows. Since Palasani is in Marwar, it is part of what ethnologist Komal Kothari [4] termed the “bajra zone”. In his work, that spanned five decades until 2002, Kothari classified Rajasthan not according to its more rigid, constructed borders of tehsils and districts, but agricultural zones that followed three kinds of millets— bajra, millet and jowar. Kothari saw the imperial categorisation of Rajasthan’s landscape useful only to regimes and conquerors. He dismissed them as arbitrary and dictatorial, and formed instead categories that synced with staple crops and food. This would, according to Kothari, give a better idea of the lives, fears, daily habits, and household rituals of the families that lived in every particular region. In Palasani, Kothari’s categorisation bodes well — Kaburi and her family talked repeatedly about how without bajra, their lands do not breathe, their stomachs do not fill. No amount of state-sponsored wheat and foraged food can account for the lack of their beloved staple grain.

But they try anyway, said Rukhsana. She recounts ‘khurat’ a dish in which gehun is boiled in water and eaten as a tasteless soup for survival. Also like Devi, they mentioned water from ‘hariya’, or green moong that grows in the village, which was sometimes used for fleeting nourishment. The women spoke more fondly of ‘bhurat’, which is a grass seed, about as big as a safety-pin, that lives enclosed in a prickly husk. “Bhurat is hard to remove, but it is good to make sogra,” Kaburi said.” “It has ‘swaad’. It can be tasty”, she added. Like Bhurat, there is ‘bakeriya’ ‑ a fodder is eaten but with derision, ‘gavar patha’ or leaves of the aloe vera plant, and ‘dhaman’, which is a grass used to feed cattle but eaten by locals during akal. There are plenty of wild grasses and herbs, but a person has to know what to do. During akal, to eat is important, but as crucial is what not to eat. “There are things in the desert that can finish a hungry man, and make people mad”, she said. “Even in akal, a man cannot be desperate. He must know what to do.”

References

[1] In her study of the travelling community, historian Yashaswini Chandra writes that while Raikas and Rebaris are abundantly used in the romanticised pictural representations of Rajasthan, they are excluded from equal access to life in the village. She terms it their “fringe position” within society and exemplifies it with a saying heard in Marwar: ‘Raah bahare Raika, gaon bahare ghar’, which translates to: “just as the Raika is outside of the mainstream, his house is outside the village.”

[2] “Seth” is commonly used for a landlord, or rich, usually dominant-caste man. Also used for a male employer.

[3] The Khejri tree, or Prosopis cineraria is a desert species native to Western Rajasthan.

[4] Komal Kothari was a musician and oral historian, who founded the organisation Rupayan Sansthan along with writer Vijaydan Detha. You can read more about the organisation here.

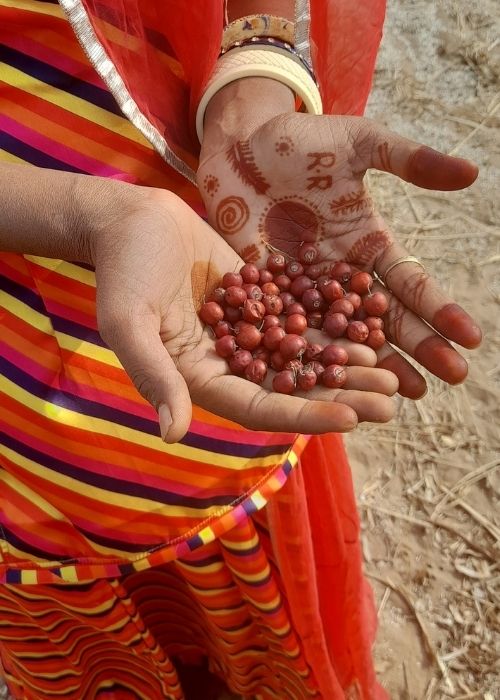

Image Caption

Left to right

- At the Arna Jharna Museum, in Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- At Rupayan Sansthan in Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- Wild berries in Palasani, Rajasthan

- The husk of bajra in Palasani, Rajasthan

- A room in Umaid Bhawan palace, Jodhpur

Disclaimer

Some names have been changed to protect identity

Birds of Hunger Part 2

Rajasthan is India’s largest state. It scales the country’s Northwest and crawls through the mighty Thar desert, which consists of the state’s primary landscape of formidable sand-dunes; terse, rocky hills and brazen, pink skies. The Thar begins in India, but stretches across hastily drawn borders during India’s independence and partition to Punjab and Sindh in Pakistan. The oft-uttered, true cliché about the Indian subcontinent being a place of astounding, unfathomable diversity; the parable that its lands hold lives stacked against one another in brutal hierarchy does only present itself in Rajasthan but perhaps derives from it. The cultures that inhabit the frontiers of the vast, vaporous desert have been unscalable for centuries, and deemed remote. Its expanse has hundreds of distinct clusters of people – both sedentary and nomadic, differing in the way they eat, live and marry. Thousands of languages and dialects populate the inlands of the desert; variable, vernacular knowledge systems exist at each sandy bend. But nation-states do not consider desert communities as holders of knowledge. They have instead been deemed hostile citizens, undeserving of attention and assistance, devoid of legitimate perspective on how to govern and determine themselves.

India, both under British rule and its post-colonial governments has treated desert-dwelling communities with a particular disdain. Through time, the region has been reduced to a merchandisable cultural algorithm devised by its most elite. Its kings and landowners have curated and sold Rajasthan as a place of colour, valour and sensualised desirability, glorifying the powerful and obscuring the lives of the its people that live and work on the land. The food of Rajasthan has consequently been depicted as one of royal ceremony and abundance. Dishes laid for royalty, ritualistic procedures that last several days and span an assortment of culinary techniques are the bedrock of stories told about the region’s cuisines. But, there are dishes that pack in rural ingenuity, stories of people eating through scalding, bristling landscapes where land does not yield to the whims of man. These remain ignored: emboldening discrimination towards certain foods and communities through time.

Durgaram Devasi is in his 70s, and works in a museum outside Jodhpur. He defines these techniques to survive famine as parampara or heritage. The same way that Kaburi mentioned the distinct grasses, Durgaram said that there are tricks to survival that are passed on from one generation to the next. “Heirlooms are not only physical” he said “Stories on how to survive the desert form a great part of what is handed down to us”. Durgaram is from Borunda, in Jodhpur district, and like Devi, he is also from a Raika family, but Durgaram’s ancestors were camel herders, who gave up their traditional trade and began to rear sheep two generations ago. As he cooked a lunch of bajra rotis and gobi ki sabzi for us, he maintained that it was through “watching, that he knew how to preserve food.” For storage, he remembered that his mother and aunt would put dried neem leaves in a large clay pot before they stored bajra in it. “This way, it didn’t get kharab. It didn’t spoil” he said. He also mentioned ‘raak chhidakna’: a preservation technique in which ash is sprinkled in a pot before it is filled with grain.

There are other techniques: like making pots out of the ‘Gadhay ka laat’ or donkey dung. “Gadhay ka Laat protects from keedas or insects”, Durgaram said. ”This is an important craft that nowadays, people do not know about.” he added. As he ate, Durgaram continued to talk about the wisdom of puraanay log or ancestors, noting how young people from his community would rather move to the city than live where they were born. “They want a job somewhere else, and not live here where the land does not give. But how can they be blamed? Am I not doing the same as well? Working for the seth in the museum? Traditional methods are good to preserve, but when history has acted harshly, one cannot criticise people for trying to abandon it” he said. Like Kaburi, Durgaram remembered stories of Chhapaniya akal told to him by his mother and aunts. He talked about ‘kheenp’, a local shrub were pasted and added into bajra to make it double in quantity, and how villagers would gather fruit like ‘guwar phali’ and ker and dry them for harsh times. “Stealing these dried items was dealt with sternly by our parents” he remembered, about being a naughty child. “Stealing stored food, and wasting. Yeh paap hai baday. These are great sins”, he added, more gravely.

Durgaram also explained that for Raikas of his mothers’ generation, they were accustomed to moving. “Because they were not always in one spot, they could fight akal.” he said. “It provided resistance against hunger. Because they could do trade, sell handicraft, and buy food in other villages where famine had not hit.” He mentioned the communities of “Bhats”, who are traditional, travelling genealogists and provided some services in his village during famine. Bhats, who would travel from place to place would transform into transporters for foodstuffs. Like roving spirits, Durgaram said, they would ask people what they needed, and if they could, bring it back. “I remember harsh times, but I also remember people taking care of each other. Sometimes chowdhry log[5] as well. But there was help from neighbour to neighbour.”, he said. When asked if the kings provided any assistance, Durgaram was amused. “Of course they didn’t help. The kings are always well fed. Have you seen their palaces? Have you seen their kitchens? They always have delicious food.” he said. “But let them eat what they want, ” he added, generously. “Humay kya? What is it got to do with us?” As he cleared away his meal, he was resolute that the kings and villagers would never understand one another. “Yes, we are all Rajasthani. But we are not the same’. Bas yaad rakhna. yeh Rajasthan ka Registan sirf rajan ka nahi hai. Just remember one thing. This desert of Rajasthan does not belong only to its kings.”

Famines, meanwhile, will continue to come. In his lifetime, Durgaram remembered moe than fifteen – some long and some brief periods of scarcity. “You know the saying? Every three years there is akal, and famine in Marwar”, he said. These days, because he lives close to a city, a car comes with food. “Gaadi no intezaar hota hai ab. Now, we wait for the cars.” He laughed. Aid used to come earlier as well. He remembered the famine of 1970, when what he calls ‘lal jowar’ or ‘red millets’ came as relief to Borunda from the ruling “Indira Gandhi sarkaar” or the Congress government of the time. “It was not all fresh, however. But we ate it” Durgaram said. He worried for those stranded in the far reaches of the desert. “The car comes here, but does it go far away? What about Jaisalmer? Barmer? Do the cars go there?” he asked. He echoed what Kaburi and Ruksana said about the further parts of the great desert. “Do you know the saying?” he said. “Famine has its feet in Bikaner and head in Pungal: it sometimes visits Jodhpur but has its permanent abode in Jaisalmer”.[6]

**

For the country’s elite, famines remain one-off occurrences, the idea of scarcity often has to do with wartime, or political emergency. But in many parts of India today, rising prices, lack of subsidies and crop failure regularly create famine-like conditions, entire regions live without proper supplies of food and nutrition, people leave their homes in search of greener pastures to grow food. Modern famine is not a complete absence of food, but it is many other things: it is the unavailability of adequate harvest to farmers; it is the slow decline of cattle, and the sharper fall in the number of camels in the state. It is the erratic functioning of the Public Distribution System; it is the Brahmanical entitlement of organisations like the Akshaya Patra foundation[7] who deny eggs and animal protein to children, who need them the most. In rural Rajasthan, famine, drought and akal are not aberrations but manifest in routine, everyday ways. They present themselves in the lack of support for irrigation, the imposition of monoculture, the presence of caste-based curtailment to food, and the constant threat to food security for the most vulnerable in the state.

The pandemic has only emboldened this. In 2020, a survey conducted by “Hunger Watch” disclosed that more than 62 percent of the respondents had to borrow money to eat. In the same year, according to IndiaSpend, in Dungarpur district’s tribal belt, communities suffered from hunger due to the loss of work, and reverse migration from cities to villages during lockdowns through the country. Like earlier centuries, even today it would be too convenient to blame these on natural causes. Doing so would ignore the myriad of ways access to food functions and malfunctions in Rajasthan. Eating in Rajasthan, then, remains a question of the fluctuations climate; and of access and distance — both physical and social from what is available and healthy. Even today, rural citizens of the state routinely walk long distances only for a pot of water for their families; ‘khaara paani’ or saline water, is still a resilient, unforgiving curse to their lands. Because of these unforgiving conditions that have persisted for centuries, the ingenuity of marginalised communities like Mirasis, Meghwals, Kalbelias and Manganiyars lie in creating possibility even as possibilities are routinely squashed by those on the top.

Like wild edibles and storage techniques, there are multiple ways that these communities have devised to battle the destruction of their lives and livelihoods. Consider that the ‘tidda’ or the desert locust – which is an excellent source of protein – is eaten during scarcity, but also as a measure to keep crops safe from the insect when it swarms. But, while ingenious, these are not always viable in the long term. Devi, Kaburi, Ruksana and Durgaram used a word when they spoke about times of scarcity — “Bas, timepass kiya” they said, when asked how else they survived these periods of hunger, how they managed to get by without any support. “We simply did ‘timepass’”. The word, timepass is colloquially used by city folk for boredom, it is associated with passing time through watching television, or apathetically scrolling down one’s phone. Timepass, heard so often as a metaphor for killing time has a different connotation to these residents of rural Rajasthan. It indicates the futility of their hardened resilience against hunger. It suggests that even when they join heart and soul to feed their families, labour endlessly to secure a future, it can be timepass and does not amount to any real change.

While Durgaram used the word, he also provided solutions to counter timepass. “Think about this, if in such conditions people manage, then what would happen if they had assistance? What if irrigation channels were made, and then sustained? What if loans were given for them to invest in farming? What if villagers were treated with the same respect as rich people in the city?” he asked. When asked what would happen, what would change, he was resolute that first these questions need to be asked, and unlike policy makers on tall pedestals, the solutions to these problems lie with people themselves. “Thodi madad karo. Aur phir kya?” he said. “Rajasthan ne sonay ki chidiya ban jaanna hai bas”. He used the same metaphor for Rajasthan given to the Republic of India when it was declared into a dreamlike state of independence. “If they would just help a little bit, then just watch. Rajasthan would become a golden bird, ready to fly.”

References

[5] In local dialects, “chowdhry”, alludes to landowners, often from communities affiliating with the dominant “Gujjar” caste

[6] Durgaram re-iterated a proverb that is also found in the text: Famine Foods of the Rajasthan Desert by MM Bhandari, published in 1974

[7] In 2019, the Akshaya Patra Foundation, in-charge of midday meals for more than 4 lakh children refused to serve eggs in their meals, along with cooking with onion and garlic. Read more here.

Author’s Bio

These essays, by writer Sharanya Deepak, who was a resident at Serendipity in 2021, take a look at the nature of cyclical hunger in the region, what people ate when all food disappeared. They also think about how stories of hunger and scarcity show up in folktales, and oral cultures like songs, and idioms. They look at alternative models of knowledge, documenting and remembering events that are relegated to peripheries by neglectful nation states.

Image Caption

Left to right

- At the farm in Palasani, outside Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- 2. At the farm in Palasani, outside Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- At the Arna Jharna Museum in Jodhpur, Rajasthan

- The rugged terrain of Marwar, Rajasthan

2.0 Birds of Hunger

How oral histories and folklore hold memories of hunger

Kaburi, Rukhsana and Durgaram often retreated to stories and songs that lingered in their minds when they spoke about memories of akal. But it is from cousins Shafi Mohammed Langa and Hayat Mohammed Langa, musicians from Badnava in Barmer, that I first learn about stories and metaphors that circle around drought and famine. Through Rajasthan, stories of great hungers are omnipresent in folkloric cultures that consist of ‘muhavaray’ or idioms; and ‘kahaniyan’ or folktales devised in local dialects. It is a telling way to think about the histories and ways of Rajasthan, whose very nature escapes linearity, whose histories are so myriad and vaporous they beckon a great deal of listening.

On the morning I met Shafi and Hayat, they brimmed with stories and conversation. Shafi took on the role of primary orator; and Hayat, almost twenty years older, provided narrative interjections to manoeuvre and layer his brothers’ macabre, winding tales. “Main jo kal tha woh main aaj nahi”, Shafi said, before he told his stories. “What I was yesterday, I am not today”. With this, he drew attention to the most crucial nature of stories and storytellers, that they change with every minute that passes in time. As I listened to Shafi, I would try and steer him back into a linear narration by the instinct that I possessed as a city-bred listener. But Shafi’s stories had their own heartbeats, going where they wanted, not returning to the initial path they started on unless they desired to themselves.

Shafi spun several tales, often possessed by the characters in them. He told of an entitled sultan capturing a beautiful tree by force; he narrated stories of a young boy, which I later found out was his own younger self, stealing ghee and gur from his mother’s kitchen until all his teeth rotted and fell out of his mouth. When he told the story of the delicious theft, he stood up in a frenzy, writhing in a make-believe toothache. His son prodded his father to sit down, handing him a glass of water, unless the older man allowed his imagination to exhaust himself. “Abba kahani sunaatay nahin, kahani ban jaatay hai ” he said to me, grinning before he took our leave for his job in the city. “My father doesn’t tell the story, he becomes it.”

**

Jismein ek Kumharon ka parivar tha aur ek rakshas [8]

In which there is a family of kumhars, and a big demon

Ek baar, said Shafi…Once, a long time ago, there was akal, or drought in a village in Marwar. In the village lived a family of Kumhars[9], or traditional potters who made pots, and cooking vessels. The family owere close and appeared to love one another. When the akal became dire, the patriarch of the house ordered his two sons to leave the village with their families. On their way to a neighbouring village, the brothers sat down under a tree to rest. What they didn’t know was that under that tree lived a ‘rakshas’ or demon, and not just any rakshas but a ‘bada-bakas’ — the most ferocious one of all. The bada-bakas travels 50 kilometres in one step, and if he wants, he can eat everything and everyone on its way. Satyanaash karay! added Hayat, with his hands in the air. He can turn everything to dust! When the bada bakas met the family, its young sons were collecting wood for fire. When he asked them what the wood was for, one boy said confidently: to burn you to ashes! The bada-bakas was amused. Wasn’t this young man scared of his grotesque form? “Aren’t you frightened?” he asked the boy. “I am the bada bakas, I can destroy everything around us just with one breath.”

The boy nodded No, and the bada bakas decided to give the wealth he had conquered from people everywhere to this family of brave young men. “I know there is akal in the village, but give these pots of gold to your mothers and tell them to make halwa-poori swaddled with ghee”, the bada-bakas said. “Your hard days are over.”

The next day, a distant relative, a ‘kumharin’ came to pry on the family. The smells of halwa-poori had reached hungry villagers, everyone talked about this family of kumhars feasted while others ceased to live. When she came, she saw the family eating halwa poori and was shocked. “What is all this? You feast while we perish?”, she cried out, cursing her distant cousins. The family told her about their luck, the young sons bragged of their courage. The next day, the kumharin came back with other family members and villagers. Everyone wanted a taste of the ‘bada-bakas ka dayn’, the gifts of the demon. But the family of kumhars had become possessive of their wealth and good fortune. When their relatives asked for some food, they guarded their dripping pots of ghee and fluffy pooris, refusing to part with even one morsel.

When the family refused to share, the villagers turned into a hungry rage. Violent insults flew everywhere, the ground shook with sounds of shouting and fighting. When the bada-bakas saw the family fight with their kinsmen, its opinion of them shifted. “I thought them brave and confident, but these people are weak. They have no support from their family and friends. They are not worth my gifts.”, the demon thought. In just one moment, the bada-bakas ate the family, once bestowed with wealth, they were now simply food. Indulgence and wealth makes a man miserly, Hayat said, solemnly. If only, they had shared the halwa poori, and helped others in times of need. They would have thrived and stayed alive.

Jismein ek bhil aur bhilni the

In which there was a couple from the Bhil Community

Far away from Marwar, in a village that is now in Pakistan, there lived a Bhil and Bhilni[10]. They were happy together and they had five children. But like everywhere, a great hunger was to strike the family. The Chhapaniya Akal of Bikrami Sampat 2056 descended on their village, and nothing was to ever be the same. When the akal came, it was a terrible drought which quickly became famine, and the famine quickly became a plague. There was no food anywhere, and the only water left was in peoples’ eyes. In the akal, many left the village for work, and the Bhil told his wife — “I must go too”. Leaving his wife behind, the Bhil travelled across the desert to find work, perhaps so far that he reached what is now India. Back in her village, the Bhilni was fraught, she did not know what to do. She could not take all her children with her, so she left the three youngest in the village and went to work for a “thakur” or landowner in a town nearby. When she left, she covered her head with a dark cloth so that nobody would recognise her – the woman who left her children to their misery.

A year passed and the akal subsided. The Bhil returned to his village, with a small bag with coins to buy food for his family. When he arrived, he found to his alarm that his wife was gone. Determined, the Bhil set out to look for her, asking for her but never finding her where she should be. Soon, he reached close to the thakur’s village, and someone gave news of a woman who worked there with three children who had his eyes. He went there and found his wife, as she wept when she saw him. “Leave me! I am no mother, as I have left our children to the great hunger” she cried. The Bhil was relieved to have found his wife, and told her about his travels, the suffering he saw. You will not be able to bear them! Hayat interjected. It is too horrendous, too Khaufnaaq, too frightening. But even as the Bhilni wept, her husband forgave her. “Akal makes monsters out of men, my wife” he said. “Forgive yourself, and now we will continue our family with what we have.”

When he ended his stories, Shafi was remorseful, he expressed concern for the family of kumhars eaten by the demon, who did not share their halwa-poori. I was self-righteous at his compassion, and asked him: “Shafi Saab. Surely, people who don’t share wealth don’t get punished that often. But they should?”. When Shafi did not respond, I apologised for trying to extract a moral from his story, that was not meant to be dissected soon after it was told. Hayat indulged me, telling me that it was lessons of humility, patience and will that are learned from stories about hunger and plague. About the story of the Bhil couple that were separated during Chhapana akal, Shafi noted how women bear the brunt during famine, and how hungry members of the family fall at the feet of their mothers. He remembered how his own mother would guard grain with her life, and sympathised with the Bhilni in his story, and the pain of prioritising your own life over that of your children. “That comes easily to men, but not to women,” he said.

***

Like Shafi’s stories, there are thousands of tales told directly or indirectly about akal. In the work of writer Vijaydan Detha, who wrote stories about and inspired by lives and obstacles of the toiling classes, the themes of akal, and food scarcity are prevalent. In the oral historian Komal Kothari’s encounters, these stories live tucked into songs, and couplets spun to preserve anecdotes of famine. In a book length interview[11] authored by Rustam Bharucha, Kothari recounts a powerful story called “Capturing the Clouds”[12], which was sung by a Bhil woman during his travels for research. In it, the woman sings about a terrible plague, and the Bhils call on their supreme “mother goddess” to end their suffering. To do so, the goddess goes to the home of a baniya, and finds that he has captured the clouds under a ‘bhatti’, or millstone. When found “these clouds escaped into the sky, the sky darkened and the rain descended heavily onto scorched lands. Everywhere rivulets and waters began flowing, and the people were happy” Kothari narrates. But the story doesn’t end there, the mother-goddess decides to punish the baniya, and asks him to sacrifice a buffalo in her name. But the baniya refuses, choosing even under desperation the instruction of his caste rather than his punishment to be able to live. The story doesn’t end before illustrating how the powerful are allowed pardons, even when they transgress.

In this way, folk tales often tell of the resilience of oppressed communities, and similarly narrate the neglect and pride of the classes that ruled. Whereas the act of documentation itself is controlled by dominant castes and classes all across India, through oral histories and undocumented tales, it is possible to glimpse the oppression endured by the millions that had little access to power and land. It is no secret that people of all kinds, from all over the world, resort to rhyme and music to be able to cloak and contextualise painful memories; and while it is cliché to repeat that Rajasthan’s lives are woven through folklore and oral traditions, it is imperative to do so to remember the multitudes of narratives left out of what we concern to be legitimate history. For the rural residents of the state, who are not members of the dominant-caste, Anglophone, post-colonial Indian nation, tales of suffering and ways to resist the same often spring up in rhymes, songs sung during farm-work and stories told by grandparents during harsh winter nights. Stories of akal remain ever present in the homes, kitchens and the everyday fabric of the people that have encountered them.

While Shafi narrated stories, he also remembered muhavray that had to do with times of scarcity. He spoke of those that included signs, of specific linings on monsoon clouds; of sudden calls by desert animals that prompt vigilance towards a turn in weather, a chance of sudden rain. “If a chameleon climbs on the upper branch of the Ker tree and changes its colours. A drought is coming. If a herd of wolves trace back their steps. A famine is on its way”, he said, recounting some favourite sayings about akal. He said that there were thousands of expressions like these, and many ways in which akal was remembered and cautioned about through the desert. “Aur na dikhay toh?” I asked him, “What if, Shafi Saab, one cannot see these signs you speak of?”. Shafi was undeterred by my question— “Jo dekhta nahi, bas usko dikhay na” he replied. “If one cannot see the signs, it meant that they are not looking.”

References

[8] I collected 4 stories in all from Shafi, even though there were small spurts of several that were told in the course of the day. Shafi oscillated between Hindi and Marwari, but spoke predominantly in the latter. These stories are from a conversation that has been translated two times over, first from the original conversation to Hindi in Devanagari script. And then from that to English.

[9] Kumhars are a sub-caste in Rajasthan known for their occupation of traditional pottery

[10] A couple from the Bhil community in Rajasthan

[11] Rajasthan, an Oral History: Conversations with Komal Kothari is a book-length interview spanning several topics written by writer and cultural-critic Rustam Bharucha, and published in 2003. Komal Kothari was a musician and oral historian, who founded the organisation Rupayan Sansthan along with writer Vijaydan Detha. You can read more about the organisation here.

[12] Capturing the Clouds has been read and paraphrased from Rajasthan, an Oral History: Conversations with Komal Kothari. The story ends with the mother goddess asking the baniya to sacrifice a grass-effigy of a buffalo, to which he agrees. But when he slices the effigy, it leaks blood and the rivers and land are coloured red with it.

Author’s Bio

These essays, by writer Sharanya Deepak, who was a resident at Serendipity in 2021, take a look at the nature of cyclical hunger in the region, what people ate when all food disappeared. They also think about how stories of hunger and scarcity show up in folktales, and oral cultures like songs, and idioms. They look at alternative models of knowledge, documenting and remembering events that are relegated to peripheries by neglectful nation states.

Image Caption

- A desert tree species at Arna Jharna, Rajasthan

- Bajra husks at Palasani, Rajasthan

FOOD AND IDENTITY: WHERE MARWAR MEETS MARWARIS

By Anmol Arora

The food of the Marwar region of Rajasthan — which includes the modern districts of Jodhpur with some parts of Barmer, Pali, Jalor, and Nagaur — is often characterised by vegetarian dishes. These include gatte ki sabzi, kadhi, daal baati churma, and bajra khichdi made with ingredients like besan, papad, daal, bajra, and curd.This popular understanding, which spans cookbooks and restaurants, is often derived from the eponymous population of Marwaris—a cultural identity that includes traders, businessmen, and merchants belonging mostly to the Vaishya caste of the Hindu caste system. They often represent the entire state’s tastes and norms because of their position in society as arbitrators of wealth and money and their community strongholds in cities across the country. They share this space with the famous princely class and the erstwhile royal families among the Rajputs.

In almost every colonial-era big port city, you will find a Marwari locality. The communities residing there are defined by their business acumen, money, and a certain cohesive identity stemming from a shared ‘homeland’. Some examples are the traditional localities of Burra Bazar in Kolkata and Sowcarpet in Chennai..While studying in Chennai, I would often visit Mint Street and browse through the intricate lanes at Sowcarpet. I would enjoy a Rajasthani thali for lunch or some sweets at Kakada Ramprasad, and walk around looking at big stores selling dry fruits, jewellery, and sarees. The proprietors would switch from a Rajasthani dialect to Hindi to Tamil in seconds, depending on the customer at their shop.

So, who are Marwaris? Are they rooted in a particular geography or a sense of place and time? What is their food like and how have they come to represent a dominant segment in the cuisine of the largest state of the country?

In her book, Community And Public Culture: The Marwaris In Calcutta, 1897-1997, historian Anne Hardgrove attempts to answer this. “The general stereotype of the Marwari businessman is a Hindu or Jain baniya (Vaishya trader or moneylender), carrying nothing but lota (water pot) and kambal (blanket), who has migrated thousands of miles from poor villages in the dry deserts of Rajasthan to cities and towns all over South Asia,” Hardgrove writes. In her research, Hardgrove found out that a majority of these Marwaris do not come from the Marwar region but rather find their roots in the Shekhawati region of the state, which comprises districts of Jaipur, Jhunjhunu, and Sikar.

The conceptualisation of the Marwari identity then is not something rooted in an actual geographic location; it is rather a reference to particular business/trading communities and their origin in a mythical Marwar, with caste and religion-specific connotations. Hardgrove explained that this mythical homeland continued to be performed and enacted in various material and cultural practises such as returning to Rajasthan for rites of passage like marriages, philanthropic ventures, and constructing temples in home villages. So, the Marwari identity, which was ascribed by the others, got eventually imbibed and imbued as their own by this community.

Also, in his article The Emergence of Indigenous Industrialists in Calcutta, Bombay, and Ahmedabad, 1850-1947, Gijsbert Oonk figures that the Marwari businesses succeeded in Calcutta during the economically unfavourable contexts created by British colonialism, and affirmed the importance of their trading, banking, and speculating background for their economic success. Even before the 20th, century, references to Marwaris have existed in historical accounts — take the examples noted in Govind Narayan’s Mumbai (An Urban Biography from Mumbai 1863). He wrote: “If a Marwadi works in a shop, he toils very honestly. Not only are they extremely frugal in food, clothing, and other matters, they even use water, which is freely available, most economically.” Here, Marwari or anything related to Marwar became synonymous with the baniyas and was also taken up by the Jain business families of Rajasthan. It came to symbolise a certain conservative value system, defined by social customs like strict vegetarianism and endogamous marriages. Their notions of purity and pollution continue to be extended to those they consider below them in the caste order and also women.

This essay doesn’t aim to provide an exhaustive anthropological or socio-political understanding of the Marwar region or the Marwari identity. It is a mere glimpse into some of these cultural norms and beliefs through perspectives that emerged from free-flowing conversations with urban women who possess belonging or have a relationship to the Marwari identity. In these conversations, I ask them about their experiences and views on food, kitchen, and eating rituals, along with the geographical and societal influences on how they cook and eat today.

Roundness of Chapattis & Wonders of Dairy

In our conversation via Zoom in December, with its inherent time lags and delays, Snigdha Bansal shared her migration story that covered Jodhpur, Jaipur, Mumbai, and now Amsterdam (her parents are currently based in Nigeria if that counts too). She identified with Marwar, “as where I originally belonged to, where my family belongs to.”

According to her, politeness and hospitality are two primary markers of the taught Marwari culture, where they always ensure that their guests eat well. ‘Sharam’ is another non-tangible thing defining the relationship with elders: “…respect towards your elders sometimes to the point [where it is] undue respect, even if they don’t really deserve it.”

This sharam, however, is primarily extended to women. They keep their heads – and sometimes faces, as is in Jodhpur – covered in front of the men and elders of the family and lower their tone while speaking to them. Such norms are learned while growing up, Snigdha said. Another thing both taught and learned in this value system is cooking.

When Snigdha was 12 or 13 years old, she moved temporarily to her grandparents’ house in Jodhpur after her grandma passed away: “Then, I started spending hours and hours in the kitchen, just learning how to make chapattis, how to cut vegetables, and how to make specific foods.” This gendered performance extended to all the young girls in the family. It was kind of fun too, getting to do it with a younger girl cousin. “She was also taught with me because it is convenient. So those times [when] we were learning together, it was fine.”And what skill determined her performance? The roundness of her chapattis. She remembered her grandfather visiting them in Mumbai, and making chapatis for him at the age of 15. “There was always a sense of disappointment both in my mom and in my grandfather, that I can’t make the roundest chapattis yet,” she said.

Men would cook sometimes too, but not every day. Snigdha shared that they would do it either as a hobby or help with some tasks for elaborate meals cooked during festivals like Diwali. While making Kabuli, a layered dish like a Biryani with alternate layers of rice, vegetables, and fried bread, an uncle would step up to do the frying. Men also took over the reins of the kitchen out of a sense of compulsion on ‘some days of the month’. That is to say, women do not enter the kitchen during their periods, a custom still followed in the household, which is when the onus of cooking fell on men.

This take on purity and pollution also extended to who was and who was not allowed in the kitchen. “I see how screwed up those things were that the caste of a person entering the kitchen was always important. So, if someone’s cooking your food, they have to be from a certain caste,” Snigdha said.

But in her nuclear family away from the ancestral land, she noticed some changes. For example, her father and brother contributed more in the kitchen, she remembered.

Something that she still follows from her upbringing is the use of ghee in food. She recounted the action of rubbing two chapatis together so that it gets coated evenly on both. Ghee is certainly a matter of prestige, but she was also taught another benefit. Since it used to be so dry and there was scarcity of water, ghee would help keep your throat lubricated, she said.A dish that she remembered fondly eating during the scorching summers in Jodhpur was chaach-roti, where you broke pieces of a chapati and mixed it with chopped onions, chaach, salt, and jira. Another was gulab ka sharbat made by her grandfather after drying rose petals for days. She remarked that it was better than the popular sharbat RoohAfza.

As she reminisced, Snigdha accepted that she did not regard some of these things with as much fondness when she was growing up. But she carried a sense of belongingness from the parched land of Jodhpur, even when she was thousands of kilometres away.

***

Roasting Papads & Winning Hearts

Chanchal Bhaniramka last visited her ancestral haveli in the Bhopalpura village of Jhunjhunu in eastern Rajasthan a couple of years ago. But she grew up in Jhansi in Uttar Pradesh, which is where her family locates its roots and their Marwari identity. Today, they primarily go to Jhunjhunu for religious ceremonies‑ like a parojan (head-shaving ceremony) for male children.Like other women of her generation, Chanchal grew up in a culture where the families focused on getting daughters married into a “good household”. Since her parents did not want her to leave home for studies, she finished her graduation and fashion designing course from her hometown Jhansi. After her marriage, she shifted with her husband to Gurgaon, where he started an IT company. She joined as the operations head, and today, has been holding the position for 15 years. Finally, she decided to do something with her love for cooking and what she called her “own cuisine”. She started a catering service from her home called ‘Marwari Food with Chanchal’.

While growing up, Chanchal said, the kitchen remained a domain for women of the household in her joint family,where they could gather and have lengthy conversations. One of her early memories is of the sitting kitchen from her paternal house, where the gas and cooking equipment like kadhais are stacked on the floor. While catering to many family members, tasks were divided – one person designated for filling the plates with food, another for taking it forth, and yet another for serving it.

She also recounted how “every wife or woman in the family would make something particular to their husband’s taste in traditional families,” said Chanchal, in affluent families, they hired cooks to help with the work. In such cases, women managed the taste of the food, checked the quality, and still made roti themselves to serve their husbands and elders in the family. She spoke of the culture where “ladies in Marwari families bathe and wear a fresh saree when their husbands come home – they look so nice, so beautiful and fresh, and they get him his dinner.” Laughing, she added, “Agar pati ka jeetna ho na to pet se hi jeetajasaktahai. You can win over your husband by feeding him good food.”

In Chanchal’s nuclear family in Gurgaon, they generally have lighter meals made with ingredients commonplace in Rajasthan like besan, papads, and dahi and enjoy Aloo ka jhol, papad ki sabzi, and other dairy-based dishes. When her in-laws visited them, she made sure to have kadhi for dinner and arranged sweets after lunch. The meal only came to an end with roasted papads. Chanchal always arranged this crunchy delight to everyone’s satisfaction.

As Rajasthan has historically witnessed a shortage of fresh produce, the concept of drying and storing ingredients for later use is a trend, Chanchal noted. Another is pickling, she explained, either preserved with salt and sugar, or just sugar in the case of mitha achar. Since many would rear cows and other milch animals like goats and camels, the use of dairy products was also common. The common dried produce in her kitchen included sangri, mangodis, and dried gatta.

Her in-laws also enjoy sandesh (a Bengali speciality) as they lived in Kolkata before moving to Bahraich in UP. “They like Calcutta food a lot — lucchi-puri, baingan bhaja — so they carry that Bengali cuisine’s influence too,” she said.

When asked, she did not think that their food was in any way frugal. She defines the Marwari taste as something that is “not very loud.” In her words, this subtlety was apparent in a Marwari woman’s dressing. As an example, she asked me to look at the sparkly diamonds on her ears. “You will find something of diamond on a Marwari lady’s ear,” she commented.

What Chanchal sees as simplicity is complicated by the Marwari’s wealth, capital, and the influence of their class and caste networks. This ‘simplicity’ too, is a cultural commodity, like their belongingness to a land — arbitrary in its contours, which they refer to for their traditions and customs.

With Purity & Portions In Mind

As someone who grew up in a Kayastha background, Payal Biyani imbibed the norms and customs of Marwari culture after her marriage. It was then that she adopted various restrictions that define how Marwaris cook and eat. “There are many restrictions, which are happening in the kitchen all the time. So [it affects] the way you start cooking, the way you finish the thalis, how you present, how you want everybody to have satisfaction in your meal,” she said. She also added that “Marwari cuisine developed around shortages and availability of food ingredients.” For example, she talked about the Annakut festival that takes place after Diwali in the month of October or November, when food is made with ingredients like moth dal, potato, radish, greens, and bajra available at that time of the year.

Payal talked about four base ingredients essential to Marwari food.“Base ingredients that need to go into Marwadi food have to be ghee — we can’t survive without ghee — and curd.” The third is dry fruits, Payal said, and the fourth is flours. The flours she refers to come from the crops that grow in the arid region of Rajasthan — like bajra (pearl millet), makka (maize), jau (barley), and besan (gram flour), apart from wheat. And nothing exemplified that more than the ubiquitous chana, which is roasted, fried, cooked in dal, and dried into flour. “Once it becomes flour, then it is multipurpose. Make snacks, make main course, make sweets with it; it has a lot of shelf life.Anything cooked with besan has sustainability over a period of time,” she said. One of her favourites is, of course, Besan ke Gatte–a dish in which‘taka’ or thin, long, coin-sized dumplings of besan are cooked in a curd-based gravy.

Payal also talked about the use of dried products that reflected the migratory nature of the Marwari business families. For those travelling often, a variety of fares could be packed for sustenance like dal ki roti. “It has crepe-like thinness. It’s very fine chapati, which is good for months and months if properly preserved. It doesn’t need refrigeration,” explained Payal. Another such item is churma, made by grinding baked or deep-fried bread.

Payal clearly distinguished between the food of Marwaris and Rajputs (another dominant community in Rajasthan) in terms of the usage of onion and garlic. Unlike Rajputs, Marwaris relied on their masala box of 12-15 spices such as cumin, roasted cumin, sonph powder, and fenugreek powder apart from salt, chilli, and turmeric. “Then, there is a lot of usage of hing [asafoetida] because there are restrictions on using garlic in our kitchen.”

Another distinction is the portion sizes that she attributed to caste-based occupations: “[Marwaris] used to be Banias. They were the moneylenders, moneymakers, merchants. So, they spent their days sitting down. Which is why the food is nutritious but the portions are small. We have five katoris [bowls] in a thali that will have very small portions.”

In Marwari households, women were often the last ones to eat. There were, however, particular rituals among women of a household, like Saasu Ka Thaal, a meal she shared with her mother-in-law after her wedding. “So, the first meal the bride should share is with her mother- in-law. We created a small thali and ate together, so that it’s the beginning of a good, compatible relationship with each other.” What was served in it? “It was only Thuli.” she said. She explained that thuli is broken wheat cooked into a texture of couscous and mixed with jaggery, ghee, and some dry fruits. She noted that the dish may have been devised by women just for themselves. “Since they were the last ones to eat, like cooks at a restaurant make a curry for themselves after service ends, maybe they also cooked something that was simple but also celebratory – so they enriched [it] with ghee and dry fruits, and added some sweetness with some gud or khand, and served it as a whole meal,” she added.

What emerges is a dietary culture that is as much influenced by its caste and religion-specific restrictions as it is by the terrain and history of the state where it finds its origins. Payal talked of “shortage”, pointing to the culinary sensibility derived from a limitation of ingredients that she said has given Marwaris “ways to think about making new recipes and variations in food [both] in terms of flavour and texture. “

***

Image Caption

Home cooked meals from the kitchen of Chef Payal