The Question of Food

By Elizabeth Yorke

This read has probably more questions than answers, But because food is so subjective, and everyone has their own story, dish, recipe, so hopefully each shall find their own understanding and perspective in connection with their relationship with food.

“When asked why we eat food, few think further than the fact that food is necessary to support the life and growth of the human body. Beyond this, however, there is the deeper question of the relationship of food to the human spirit. For animals it is enough to eat, play and sleep. For humans, too, it would be a great accomplishment if they could enjoy nourishing food, a simple daily round, and a restful sleep.”

Masanobu Fukuoka, The One-Straw Revolution

Food is a crucial part of our human life. One of the big concerns during the pandemic, apart from access to medical care of course, was food. How would we get our food during the lockdown? How would it make its way into our cities? Who would feed us? Who feeds those who feed us? How do we feed ourselves healthily? How do we make sure our loved ones are fed with care? How can we help those who don’t have access to good food? Can we cook for/with others from a distance ?

During these times of distress and the unknown, there were many changes in our food system that exposed cracks; right from how produce reaches the city to how we communicate and even what and how we eat. But these cracks were soon filled with some concepts that now seem to have become part of our everyday lives. We saw technology break new barriers – cookalongs over WhatsApp or Zoom, food groups that shared recipes, Instagram feed documenting food and tradition, courses on studying food and how to go about food research, QR codes for everything – reading a menu, buying food, tracing food, paying for food.

So, while for some the quest for (good) food was more of an immediate need. For those of us locked in we used food to pass time, as a distraction. We posted on social media, made our banana bread, shared recipes, and started looking into our food cultures and traditions.

Maybe we started to think about food beyond feeding ourselves. Maybe we asked ourselves how some others were being fed or how in the past, such disasters affected communities and food cultures? Maybe we had conversations about what was “good” and “healthy” food, and how someone else’s choices may not be the same preferences as ours.

Creating room for these conversations, thoughts and expressions was an important part of the Serendipity Food Lab residency.

We envisioned a space created to experiment with these thoughts & ideas, stir up conversation, slice through research, sieve out the social stigma, simmer on unintended consequences, and taste new ideas and ways to take perceptions and inquiry of food forward.

The residency was set to run as a hybrid model from August to November curated with talks, workshops, cookouts and cookalongs, fieldwork – with the pandemic ensue, the residency took its own virtual path with learnings and conversations from around the world.

What do Famine Foods and Insect Eating Have in Common?

Meet the Residents: Tansha Vohra and Sharanya Deepak

It had rained the entire week and meeting in the park might not have been the smartest idea. But the weather held, and under the lush canopy of cubbon park we had our first and only in person residency meeting.

Socially distanced-ish with some almost crispy vada+chutney, sugary kesari bath and hot-hot filter coffee, the excitement and apprehension was evident about embarking on this residency.

Writer and editor Sharanya Deepak, was keen to take a dive into the past, move away from taste-centred gastronomy and understand the deeper meaning that the word cuisine holds. What do we come to know as traditional? How have our food histories been based on ingredients, experiences, cultures and recipes of social upper castes and classes. Who controls the narrative. This questioning created a space to take a look at periods of time when food was scarce, frugality was a necessity and physical and mental trauma has lingering effects even to this day: famine.

Sharanya’s enquiry into this space started from a piece she wrote “A ‘Forgotten Holocaust’ Is Missing From Indian Food Stories” in Atlas Obscura. This was a story to understand the impact of the Bengal Famine(s) on food cultures and their representation in food writing, cookbooks & recipe blogs.

The foods of the Bengal Famine, though, remain absent from accounts of the region’s and India’s cuisine. Indian food annals ignore the moments of hunger endured by millions, focusing instead on taste-centric gastronomy, laying out tables of opulence and abundance as normative, and foraging the past for pleasantries to set as placeholders for the history of Indian cuisine. Meanwhile, foods that feed and continue to sustain the powerless remain largely ignored.

Excerpt from “A ‘Forgotten Holocaust’ Is Missing From Indian Food Stories”, Sharanya Deepak

When we think of Indian food and food cultures & tradition, famine histories aren’t the first thought. Should we be looking into the past to better understand the future or should these painful food memories be erased all together?

“Even as the famine was a time of adversity, who bore it?” asks Sarkar, when he talks about interviewing survivors in Medinipur and other rural pockets. The adversity of the Famine was not suffered equally. “That is why these foods are not written about at length. These were not literate people, they did not document. And also, these were memories and recipes associated with shame,” he says. “Why would they want to relive them again and again?”

Excerpt from “A ‘Forgotten Holocaust’ Is Missing From Indian Food Stories”, Sharanya Deepak

Sharanaya’s work through the residency was centred around the Marwar Famine of 1869. She looked into the significance of hunger of the region and greater Rajasthan and what ingenuity and resilience look like in these harsh times. Her work also explored the obstacles in studying such histories, and asked the question of if traumas like this should be preserved to teach us about how the past can circulate to the future, or be buried?

“I want to free the idea of food from taste-centred gastronomy, and in the same, throw light on foods that fed hunger in a way that is not patronising, that is, I don’t wish to call them “humble”, or “minimal” but situate them in a context and attribute to them the value and worth they deserve.”

Sharanya Deepak, SAF Food Lab Resident

Sharanya Deepak’s four part essay can be read here.

While we chat, our eyes simultaneously tune into this ant, ambitiously making its way across our picnic blanket straight for the bright yellow kesari bath. We recalled how as kids, we’d been told, if there are ants in the sugar, go ahead and eat them, it will improve your eyesight. But those stories were not always bug-positive. We recalled moments of how a very common reaction to insects was disgust. And unfortunately, that was the reaction not just towards the class of invertebrates but towards the human being who ate them too. In a world where food to all people is not accessible, where geographies, cultures, tastes and preferences are so varied, when did it become okay to shame someone for what and how they ate?

Tansha Vohra, permaculture designer and journalist, recalls the first time her mind forayed into insect eating.

These conversations usually come to an abrupt halt when one of us jumps out of the hammock because a weaver ant had gone into a place no weaver ant should ever go. I give the ants a customary swipe, and for a brief moment, a scent rises to meet me — so sour, I can taste it on my tongue.

Excerpt from Hungry for Insects, Tansha Vohra

The ants were subsequently harvested and eaten and this gave Tansha a taste of what the Boochi Project could be.

“Boochi will aim to shed light on these disappearing voices, while being a resource for anyone thinking about innovation and regenerative design in the sphere of entomophagy.”

Tansha Vohra, SAF Food Lab Resident

The Boochi Project, although rooted in the past, is a clear invitation to think (and taste) the future. Although insect eating seems to have roots in scarcity, and is surrounded by shame and social stigma, Tansha believes that preservation of insect eating cultures and tradition can create pathways for resilient and sustainable food systems in the future.

“I hope to be able to hold a space for a community that encourages sustainable entomophagy, and is a breathing archive of incredibly valuable traditional wisdom that is on the brink of disappearance.”

Tansha Vohra, SAF Food Lab Resident

As Tansha continues to forage ants and experiment with other insects, (she also writes this (hilarious) guide to harvesting weaver ants for “fellow curious city dweller with no idea of how the heck one would collect biting ants to eat them”) it is important to her to build a community and keep the conversation alive. An Instagram feed, The Boochi Project, documented Tansha’s explorations, conversation with experts and collective knowledge. She started working closely with Lobeno Mozhui (a food researcher from Nagaland who is studying edible insects), Geetika Saikia (a homecook), Peter Fernandes (Permaculture Designer and Regenerative Food Grower) and many more experts from the field to start curating a better understanding of insect eating in India.

Boochi is a digital exploration of entomophagy, or the practice of eating insects in India. Many communities in India have a rich heritage of entomophagy that has been shaped by geopolitical, religious, socio-economic and environmental factors. Boochi is an inquiry into what has changed, why it has, and whether eating insects might actually be a thing of our collective future.

Tansha Vohra, SAF Food Lab Resident

Follow Tansha Vohra’s project on Instagram here

Read her live journaling through the residency in MOLD Magazine

Fill your shoulder-bag full.

It is so heavy

You can barely carry it

On your head.

Also catch the rats.

Carry flint with you.

Collect sticks in the woods.

Make a fire.

Roast the rats.

Carry the remains home

For Mother.

Collecting Wheat // Is Hunger Gnawing At Your Belly? By Rajyashri Goody

While insect eating and famine foods very evidently have much in common – from insects being eaten in scarcity to insects being studied as a solution to food security, is it merely isn’t enough to talk about the common, evident aspects – hunger, famine, feeding the planet. A closer look tells us about socio-economic issues, colonialism and caste, politics, gender and more.

Through their projects, Sharanya Deepak and Tansha Vohra dig deeper to understand whose stories these are and how these spaces of inquiry have affected communities.

Ferment, Pickle & Preserve

On Process and Outcomes

“Are we brave enough to love what is ugly inside and transform it? Are we brave enough to imagine a food system that does not involve old paradigms of poor farmers versus conscious consumers? Can we imagine a chain of production that is truly diverse and integrative? Or are we committed to what we call “the reality we have to reckon with” and unable to dare ourselves to take bigger risks both in our personal and public lives?”

THE UNSEEN AS FERTILE GROUND FOR NEW WISDOM by Vivien Sansour

The food system is complex. How do we make sure we don’t get stuck in our silo’s of thought or have tunnel vision?

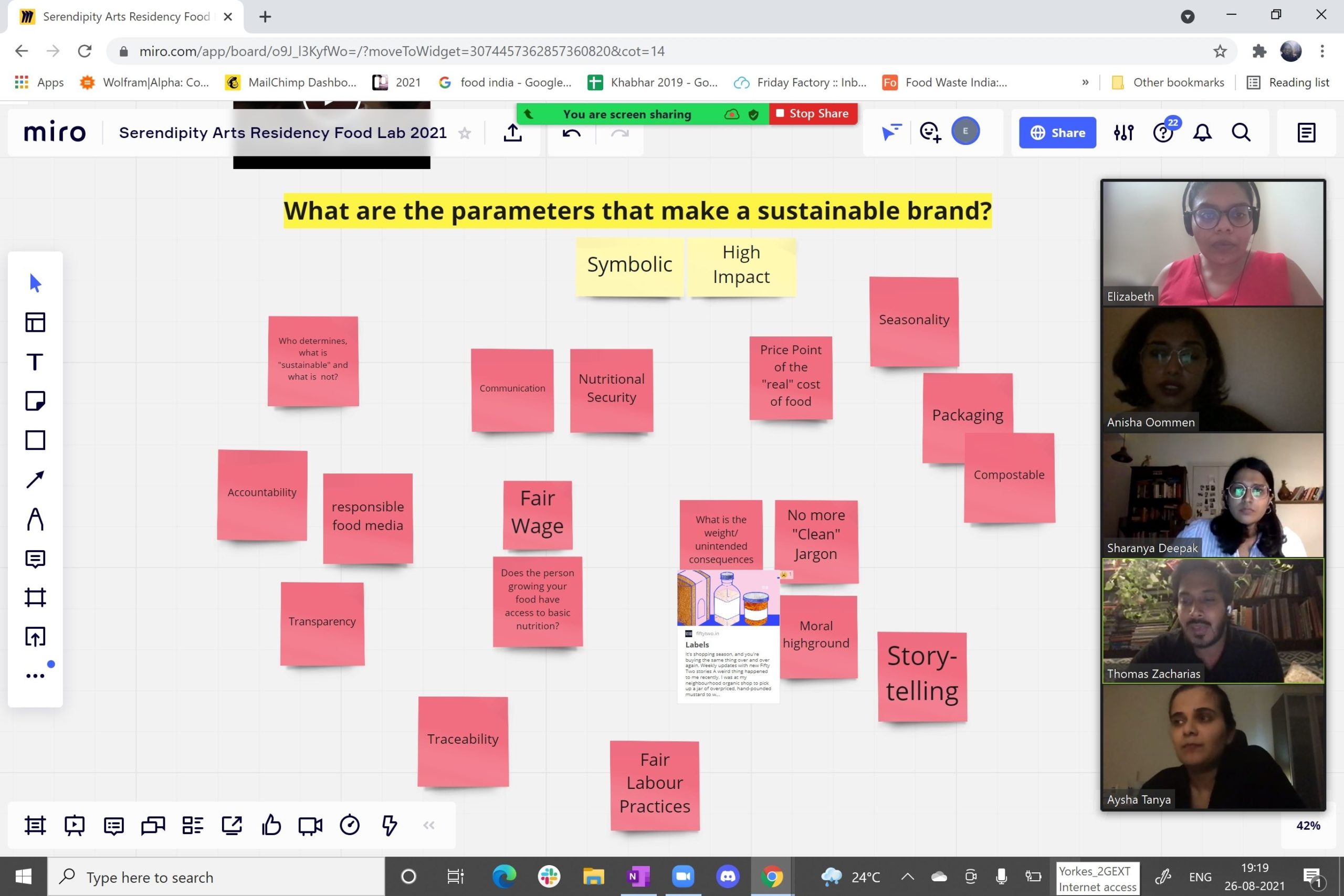

Our virtual residency was programmed to understand and explore the food system broadly through conversations with experts and fellow researchers. We also workshopped, mind mapped and brainstormed to try and build on existing knowledge, frameworks and ideas.

Food and the physical component it presents has a very strong and deep connection. To take the physicality of food out of the residency was challenging – it was like removing all the senses that came before we comprehend what that bite/morsel of food means – the smell of food cooking, the sound of preparation, the physical touch of breaking and sharing, commensality, community.

We worked our imagination as we virtually met with people in their food-workspaces to not just think, but be able to use their words and ideas as ingredients that we would later on combine and cook into what would at the end of the residency, a culture/ferment to take our conversations in food forward.

We traced the food as it moved through the system. Right from concepts in growing food, to manufacturing, buying, and eating we looked to learn what resilient foodway meant to people and their communities.

“Life Above the Soil is Supported by Life Below the Soil”

Manoj Kumar, CEO of the Naandi Foundation shared with us their vision to address India’s broken food system – Arakunomics. Arakunomics is an integrated economic model that ensures profits for farmers and quality for consumers through regenerative agriculture.

Conversations moved around the diverse and complex challenges of Indian agriculture, questioning the real cost of our food, how life above the soil is supported by life below the soil, and how crucial the role of biodiversity is to this vision of a resilient food future.

Dr Sheetal Patil, spoke to us about her current research at UPA – Agri (upagri.net) which examines the impacts of urban and peri-urban agriculture (UPA) on built infrastructure, ecosystem services, land and water use. We spoke about how more curiosities on what and how we eat during COVID have created more spaces for inquiry and action in the urban food system to look for options to be more self-sufficient. We also talked about the role of urban farming in providing food and nutrition security, especially to socio-economically marginalized urban communities. And how by shifting from a metropolis to an agropolis there is so much potential for more resilient local food systems that meet climate, sustainability and nutritional goals.

From the coffee growing regions of Araku and urban gardens in Bangalore, our residents moved into the bustling city of Chennai where they met with Vidhya Mohankumar, Founder, Urban Design Collective.

In the early stages of the pandemic and lockdowns the Urban Design Collective, a collaborative platform for participatory planning to create livable cities, took the opportunity to understand who actually feeds their city, Chennai, and how the solutions created by the disruption of these supply chains may continue post-COVID.

Their work focused on what we can learn from such scenarios and how building food smart cities, where public and private actors can focus on creating a sustainable urban food system that enables social inclusion and access to safe and nutritious food, engenders more resilient urban spaces.

“What were the circumstances in which people ate what they ate?”

We also talked about Unintended Consequences in the food system, and what the impacts were of some innovations & solutions that we’re built thinking about bettering society.

We listened to stories of the green revolution and asked ourselves some questions — What were the intended consequences of those “innovations” and interventions in Indian agriculture? What were their unintended consequences and what can we learn from that? How do we shift our thinking to minimise certain such consequences whether it’s through building a new product, researching food with a community, or jumping on a new fad or trend?

We then started to think about our own projects and what potential futures did they hold.

We used an exercise called The Futures Wheel, by Cecilia MoSze Tham, Founder and Principal Futurist at Futurity Studio.

Migration, due various reasons, has created an interesting display of mutating food habits.

Sreejatha Roy takes us on a virtual tour of the Food Lab at Museum of Food in Khirki and Hauzrani, two adjacent neighbourhoods in the heart of South Delhi, that have been the hotbed of migrants coming from across the country and even international borders.

“The local migrants and especially the ones rooted off their native places, carry ‘food practices’ as one of their defining identities to the new place. This explains the growth of places serving different cuisines in the cities across the world which have seen streams of local and international migrants. In this context, the idea of exchanges through food forms an essential component of our social bonds.”

Museum of Food, REVUE

In the Food Lab each of the participants, create a “pop-up” like food experience in the kitchen, exchange recipes and share techniques, adaptation of ingredients etc.

“Such communication also enables them to share personal recollections of their families and relatives, their home/social life in their diverse places of origin, the environments of the kitchens they left behind upon migration, and the practises, protocols and habits around their traditional foods that they seem to treasure as a natural, tangible form of personal and cultural inheritance.”

Museum of Food, REVUE

As we build on our projects and look towards the numerous potential futures, we’re staying vigilant, mindful and conscious about what kind of impact our work could have on communities and the earth.

“This is about the culture of food, and not food itself”

In 2021, the Global Hunger Index, ranked India 101st out of the 116 countries. With a score of 27.5, India has a level of hunger that is serious.

We looked to Benjamin Siegal, Associate Professor of History at Boston University to help us understand hunger through the lens of culture, economy and politics. Siegal is the author of the book Hungry Nation which is an account of independent India’s struggle to overcome famine and malnutrition in the twentieth century.

The Chapter titled Self-Help Which Ennobles a Nation was particularly interesting for our residents. It touched on the themes of transformation of diets, weaning the population off of wheat and rice, some sort of culinary confidence struggles, socially inferior foods, food technologies that don’t seem to be meeting people’s needs, and the role of women in the conversation of food.

“Indians, in the mid twentieth century as today, wrestled with questions about caste and religion. They worried about broader standards of living, fought for access to infrastructure, courts, and consumer goods, pondered India’s role in the world and negotiated the tensions between country and city, group and nation. Yet they often touched upon these questions through the problem of food, whose severity hit them viscerally as they stood in ration lines, worked in fields or even bought grains in the marketplace”

Benjamin Siegal, HUNGRY NATION, pg 5

What was famine and hunger in Indian history like under British rule, who did it affect the most aad why these events are buried and food/recipes not documented? Sharanya Deepak’s inquiry into these tough and cruel times takes us into conversations beyond just the food itself.

Often in harsh circumstances a kind of resilience is born that survives unto this day, but How are some food cultures born from frugality or survival? How do these foods, now that they have become “novel” make their way into commercial kitchens, and what is the responsibility of the chef/restaurateur to communicate these food origin stories. How should the ingredients be spoken about?

The art world was not always as fragmented as we see it today. Food was represented and tasted in music, dance, theatre and not merely as an art form on the plate. Sharanaya Deepak also finds how histories of famine have leaked into oral traditions and performance art, particularly in puppetry, folk singing.

The seeds

Of the cactus fruit

Are so hard

They cannot

Be broken open

Even with pliers.

Tiny as jowar grains.

They go down the throat

And then

Through the stomach,

slide into the intestines,

Where they become

Slabs of concrete.

Rajyashree Goody, Cactus Pods // Are You the Master of Dead Animals

“Don’t Yuck my Yum”

At a glance the narrative around Indian food and cooking brags about our diverse food cultures, ingredients and delicious dishes. But who’s food is that really? Who has representation at the table?

“You can find ragi mudde in Military Hotel menus, or at Gowdru Manes, drenched in ghee. But when my mother and her siblings packed leftover mudde from breakfast as lunch for school, they would hide, away from their classmates and far from the school grounds, eating quickly before they could be discovered. Our existence and our life experiences, our memoirs and autobiographies, are works of resistance. Our eating practises, too, are a protest.”

Vinay Kumar; Blood Fry & Other Dalit Recipes from My Childhood (The Goya Journal)

More than often food cultures in India are representatives of social hierarchy and caste and we find everyday dietary practises and food preferences are dictated by upper caste sensibilities. Food identity has long been a means of securing power and oppression – from colonisation to casteism.

We look to Dolly Kikon’s paper titled “ Dirty food: racism and casteism in India” where she offers the concept of ganda (dirty) food to highlight how casteism and racism are informed by an upper caste reasoning of superiority, contamination, and privilege in India.

“Who has the monopoly of banning food or defining what is edible?”, Asks Dolly Kikon.

In this exploratory journey of food, art and culture how do we de-stigmatize something so deep rooted, how can we replace disgust with curiosity or tolerance?

A starting point can be by simply acknowledging privilege, caste and coming clean about our histories to give way for more free-er conversations, exchange and tolerance of cultures through food.

Watch Tansha Vohra in conversation with Dolly Kikon here

“This kitchen has opened up different perspectives.”

Food may not start or end in a kitchen, but it is a space that many food stories do begin.

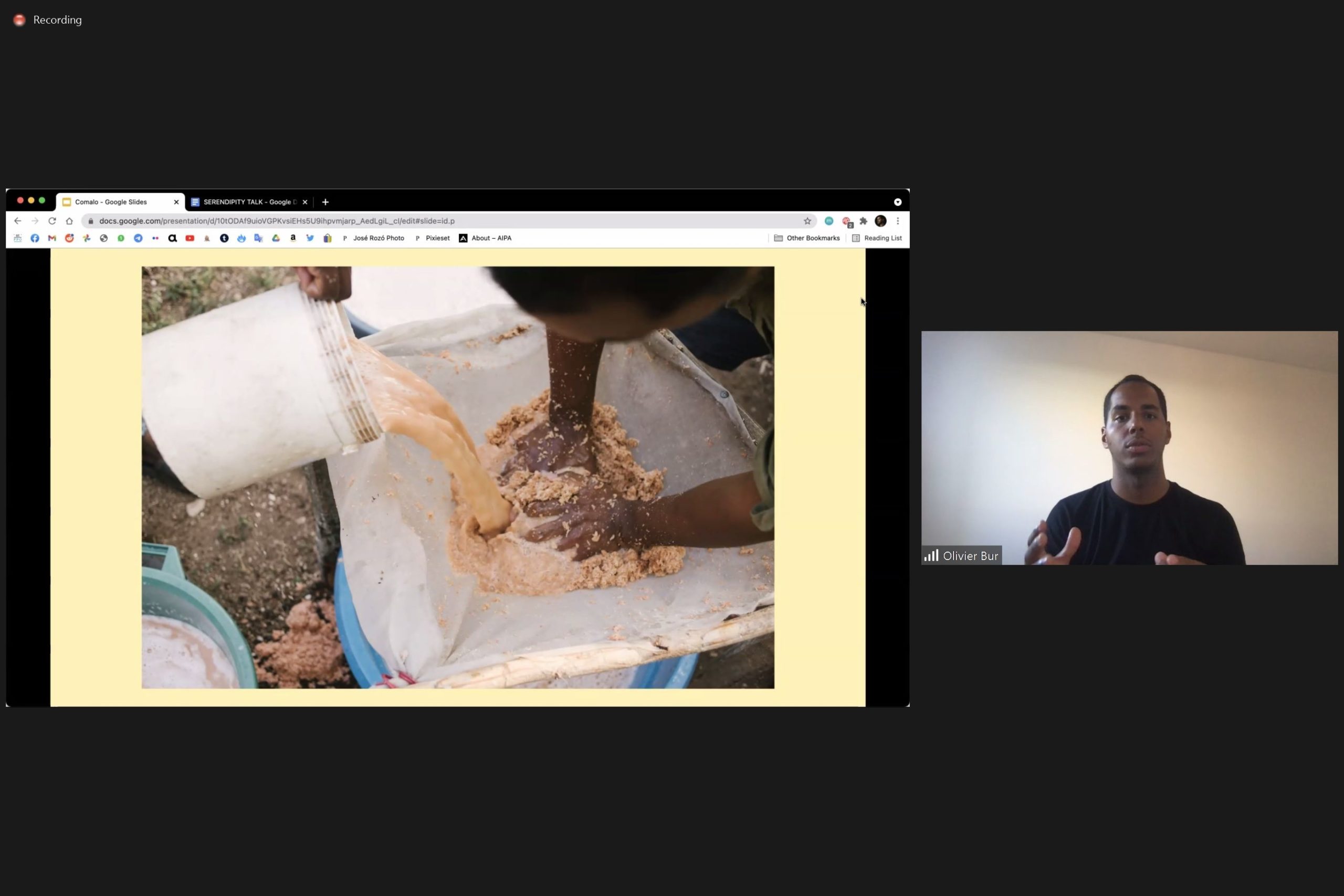

On our quest for answers and perspectives on documenting food origins took us (virtually) halfway across the world to visit the Dominican Republic where the initiative COMALO started by Chef Olivier Bur and photographer Jose Rozon look to close the gap between culinary heritage and people by feed curiosity and share knowledge on biodiversity of ingredients in the caribbean, ancestral techniques and connecting with other crafts that are part of the culinary identity.

“The main spark for my interest is to uncover knowledge around food that has been ignored because of social elitism or marketing pushes. The availability of information has always been through institutions that showed us ‘the right way’ of sitting down on a table or steaming white rice. There is not a right way of making plain white rice or moro de guandules. There are different variations and techniques that make this a rich subject to explore upon and share with others. As long as I am experiencing these traditions I will talk and share them.”

Jose Rozon, Photographer, COMALO

Excitement, curiosity, some apprehension and lot’s of stories, about food and beyond bubbled out of Tansha Vohra’s kitchen. A few curious food friends came together to experiment and participate in a Boochi Cookout. With each ingredient (insect) tasted a new idea or perspective came along. A new way of fermenting or cooking, a new person to connect with. In a few hours we experienced that journey of The Boochi Project. We talked, cooked and tasted the future of food.

“Chefs often search for something new. new ingredients, new techniques. Today old, almost forgotten ingredients and techniques are looked at as new and trendy. I was asking myself if by only learning the technique and taking them to the urban area I would really make a change or just “steal” some knowledge from them…”

Olivier Bur, Chef, Culinary Researcher, COMALO

The cookout menu had cricket flour akki rotis, neer dosa, weaver ant chutney, black soldier fly larvae meal podi, and a whole host of chutneys. For dessert, we had roasted cricket and weaver ant chocolate bars, and dehydrated BSF dipped in chocolate.

Although the concept of eating insects was new to everyone in that kitchen, the food that was prepared was inspired by local and foreign techniques, influences and comforts. What do innovations on traditions mean to food cultures? How does evolution and inspiration play into the way we could eat? What food stories will the kitchen at The Boochi cookout have told for the future of insect eating in India?

“Sustainability is a journey and not a destination.”

Now as eaters, shoppers, diners, consumers we’ve all heard that our participation in food is an agricultural/political act and that we need to “vote with our forks”.

Whether we work with food directly or not, we’re all consumers of it in different forms. Right from the edible on our plates to the inedible like on social media. What does our participation as cooks or eaters mean? How does our engagement with “better” brands/producers have an impact? What do good choices mean? And what do our choices mean for those who produce our food?

Together with The Goya Journal and Chef Thomas Zacharias we tried to map out and understand “What does it mean to be a conscious consumer?”

Language and communication has tremendous power to engage us in consciously or unconsciously making choices.

How much do we know about our food system? Do we know enough to make decisions that will create a positive impact? What does local, seasonal, regional even mean to us when we live in such a big demography and geography?

How do we see ourselves represented in this conversation on sustainability when it comes to sourcing or buying food?

While markets and the economy sees us as consumers, what if we shifted our mindsets from being simply transactional to a more integrated part of the system. What if instead of consumers we can be citizens?

a food citizen where we engage and practice food-related behaviours that support, rather than threaten, the development of a democratic, socially and economically just, and environmentally sustainable food system. (Wilkins, 2004)

By shifting our mindset to take on a citizen role, we could unlock the potential to be more mindful, nourishing, supporting, nurturing of those that produce and manufacture food within our community, and create more pathways for stronger, resilient and localized food systems.

You and I Eat the Same; But Do We Really?

On Translating Food Research into Art ? How do we navigate through food research especially when it’s trying to document or understand more difficult narratives like, famine or shame?

? Once we understand these stories more deeply, how do we tell them responsibly so that we’re not taking away anything from the community, if it isn’t our own?

? And in what ways can we use food as a tool to have these larger conversations on our food cultures and complex food systems in the arts and festivals space!?

As the residency progressed our residents had to take their research and build it into spaces that do what art does: communicate, provoke and further ideas/thought.

We realised that research in food could be used in the art space as a tool to deepen our understanding and confront socio-political, cultural and economic issues.

Given a platform, invisible communities and their narratives could be made visible through research, documentation into food culture.

We moderated a panel discussion titled “Festivals beyond the Plate: Conversation on Food in the Arts” as part of the British Council’s Festivals Connection Programme.

The panel included — Aruna Ganesh Ram, artistic director of Visual Respiration, Prahlad Sukhtankar, founder and managing partner at Black Sheep Bistro, Sidharth Sharma, creative director of Shambala Festival and director of Bristol Food Network, and Virkein Dhar, founder of Poppy Seed lab and Sundooq. The session was moderated by Elizabeth Yorke, co-founder of Edible Issues and programmer of Food Lab 2021.

The panellists gave us insight into their work with food in the arts space as artists, festival directors and food industry professionals and spoke from experience of how food can be used as a tool in the arts space to highlight socio-political, economical, environmental and cultural challenges.

Since food is so interconnected with various aspects of life, art-spaces also prove to be a vibrant test bed for ideas for the future. Visitors to art spaces come with a more open mind and thus art platforms can use those opportunities to present what otherwise are radical ideas (like insect eating) and can be used as a starting point for some of these tougher conversations. These social interactions with food could also create positive changes in audience behaviour and subsequently have a positive impact on larger food system issues.

Such presentations of work could also seed ideas and learnings for the future. The celebration of food through tasting, smelling, cooking or eating make way for indigenous and sustainable.food ways.

Art platforms can also be a wonderful place to simply celebrate the craft and techniques of food making. Food in India is diverse with rich narratives and complex histories. Is there a way we can take our culinary repertoire to the next level but through a less lavish approach? The culinary arts has been seen as a place of privilege. How can we make every plate our stage? How do we change our approach to be minimal, accessible and like food – for us all.

While our excitement about trying something “new” (new to us, but everyday to someone else) or searching for solutions for the future is important, it is important not to forget about whose story it is we are telling and how the dissemination of this information could impact the community.

“There was so much I wanted to ask. But who am I to convince this family to stick to their cultural heritage and culinary traditions? Would I choose to make my living by hard work and heavy labor or to make the money I needed to survive more efficient? Who am I to tell this family that if they don’t keep the tradition of this particular bread alive, it might be forgotten? In what position am I, with access to education and social security, to ask for more?”

Olivier Bur; THE JOURNEY TO GUÁYIGA BREAD, Whetstone

Where do we draw the line while documenting someone else’s food culture? How do we think about oral histories when documenting food, and why are these not considered part of established research even though most food history is passed on through the same?

How do we ensure that our work/research is made accessible to people beyond a digital/english forward medium?

Our conversations are nascent and we don’t have the answers yet, but being conscious about how we use our words, being inclusive of the community we are representing and being openly accountable for our actions can be a start.

A Recipe for Food Research

“If you really want to make a friend, go to someone’s house and eat with him…the people who give you their food give you their heart.” Cesar Chavez

INGREDIENTS

- One large thought about if the kind of research one is undertaking is suitable

- A large dose of consent (not substitutable)

- A conversation on what is needed in food-writing and research today

- Copious amounts of fact checking

- A quart of commensality (if possible)

METHOD

- Blend Ingredients together, let them stew. There is no rush on time – make sure all the flavours are extracted from the ingredients. We don’t want any waste!

- Strain out any bitter notes.

- If concerned or apprehensive, ask a friend/many to taste.

- Season well with feedback.

- Serve warmly and make sure it is accessible to those who inspired the dish.

Notes:

- This recipe is constantly evolving and would be different in varying circumstances. If you have more ingredients to add, please add them in and share them with us!

- Treat all ingredients with the utmost care and consideration.

- Always remember that if the dish (story) is not our own, we are only the cook (messenger) trying to tell the story in the most delicious and non harmful way possible.

Perspective is a beautiful thing

What is the Future you Envision?

One very striking story during the first wave of the pandemic came for a biscuit we all know and love – Parle-G. A favourite biscuit brand, and has been around for 8 decades. During this crazy time, Parle-G reported it’s highest sales. Ever.

Irrespective of who you are, your gender, caste, ethnicity, political leanings, socio-economic status, Parle-G was common to all.

Reverse urban-rural migration caused Indians who had to walk distances like 600 kms to stock up on Parle-G because it was the easiest, affordable, available source of glucose; while rich/middle class India stocked up from online grocery delivery and double dipped in their chai.

This parallel and divide in India exists, blatantly and it is impossible to talk about food in any form without addressing these issues. But what is interesting is the neutrality of Parle-G.

Shaping a food residency in India to be more like a biscuit may seem a bit out there.

But humour me for a minute.

Like the versatility, neutrality, reach and of course tastiness of the biscuit (especially when in chai):

- Can we have larger engagement with communities?

- There are enough stories to be told, how do we get more artists to participate?

- Can we break down the various, multitude aspects of food; addressing topics that are often neglected.

- Can we create smaller packets of opportunities in food & art to explore the numerous topics out there.

As sociologist Amita Baviskar describes it, Parle-G is a symbol of aspirational equality that we believe a good resilient food system post COVID should bring about

Programming at the Food Lab 2021

We are grateful to all the speakers for taking to the time to have insightful, stimulating and eye opening conversations with the residents at the Food Lab

- Manoj Kumar, Nandi Foundation – Arakunomics: A Vision for a Better Food System

- Dr Sai Bhaskar Reddy Nakka – Good Stoves

- Sheetal Patil, Azim Premji University (Small Farm Dynamics) – Shifting Agro-cultural Ecologies during COVID

- Vidhya Mohamkumar, Urban Design Collective – How to Map a Food System

- Julia Dalmadi, Future Food Institute – Unpacking Nutrition – Stories of food and ideas of health from around the world

- Khushboo Gandhi, Go Do Good – Making with Waste (workshop)

- Anisha Oomen & Aysha Tanya, The Goya Journal and Chef Thomas Zacharias – A Guide to Better eating (and better Living)

- Sohail Hashmi – The Myth of Traditional Cuisine

- Chef Manu Chandra – Cooking our Food Histories

- Chef Olivier Bur & José Rozón – On Documenting Food Origins *Serendipity Arts is grateful for the support received by the Embassy of the Dominican Republic in India for this online event

- Sreejata Roy, REVUE – Migration and the Living Lab

- Zackery Denfeld, Centre for Genomic Gastronomy – Exhibiting Food Systems Research

- Benjamin Siegal – Hungry Nation: Food, Famine, and the Making of Modern India